Top Gear's Target Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

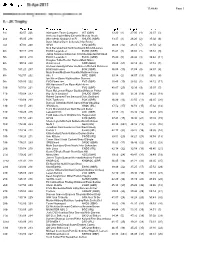

Relay Results

11:48:48 Page 1 1st 92:57 226 Interlopers Team Compass INT (GBR) 33:20 (1) 27:00 (4) 32:37 (3) Anthony Squire/Oleg Chepelin/Murray Strain 2nd 95:05 236 Who needs Graham? or R SHUOC (GBR) 33:37 (3) 26:26 (2) 35:02 (6) Dave Adams/Dave Schorah/John Rocke 3rd 97:03 240 SYO1 SYO (GBR) 36:28 (12) 28:37 (7) 31:58 (2) Nick Barrable/Neil Northrop/David Brickhill-Jones 4th 97:17 219 EUOC Legends 2 EUOC (GBR) 35:41 (7) 26:03 (1) 35:33 (9) Jamie Stevenson/Duncan Coombs/Alasdair Mcclead 5th 99:13 218 EUOC Legends 1 EUOC (GBR) 35:49 (8) 26:42 (3) 36:42 (11) Douglas Tullie/Hector Haines/Mark Nixon 6th 99:14 230 Robin Hood NOC (GBR) 39:48 (21) 28:14 (6) 31:12 (1) Andrew Llewellyn/Peter Hodkinson/Richard Robinson 7th 101:21 207 BOK Hurricanes BOK (GBR) 36:05 (10) 31:09 (8) 34:07 (4) Mark Bown/Matthew Franklin/Matthew Crane 8th 102:57 202 Aire 1 AIRE (GBR) 33:34 (2) 34:07 (13) 35:16 (8) Ian Nixon/Steve Watkins/Ben Stevens 9th 105:00 222 FVO Flyers too FVO (GBR) 38:46 (19) 28:02 (5) 38:12 (17) Will Hensman/Tom Ryan/Kyle Heron 10th 107:53 221 FVO Flyers FVO (GBR) 40:07 (25) 32:39 (9) 35:07 (7) Ross McLennan/Roger Goddard/Marcus Pinker 11th 110:04 237 Big city in England SHUOC (GBR) 36:03 (9) 35:39 (18) 38:22 (18) Robert Gardner/Tom Beasant/Chris Smithard 12th 110:09 208 BOK Typhoons BOK (GBR) 36:39 (13) 32:55 (11) 40:35 (20) Duncan Girtwistle/Keith Agmen/Huw Stradling 13th 110:17 201 3ROCkets 3ROC (IRL) 37:52 (17) 34:53 (15) 37:32 (14) Colm Moran/Andrew Quin/Gerard Butler 14th 110:29 245 Lakeland OC LOC (GBR) 34:18 (4) 33:42 (12) 42:29 (24) Todd Oates/Jack -

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

IN the RING TAXI Sabine Schmitz Treats Dieter Losskarn to the Most Intense Ten Minutes of His Life

78 CAR CULTURE ❘ THE RING QUEEN 79 11 TO TAKE A RIDE: IN THE RING TAXI Sabine Schmitz treats Dieter Losskarn to the most intense ten minutes of his life. The Ring Queen and her hell-toy, a BMW M5,reigns supreme Just as well Dieter didn’t have time for PHOTOGRAPHY: WAlTeR MathiAs Wilbert & DieTeR LosskARn breakfast. Sabine’s warm-up lap is lightning quick Sabine in action Imagine A wOman TODAY BMW STANDS for ‘Breakfast Must Sabine’s current Nordschleife lap count is public one-way road. Yes, public. The 20.8km Wait’. If you intend to join Sabine Schmitz about 24 000, nearly 1 200 laps a year. Her Nurburgring is part of Germany’s road system. The famous Top Gear video, where she around the 73 corners of the world’s most mantra: ‘Everybody can drive fast on the In case of an accident (several during public throws a Ford Transit around the ring in record time: who cAusEs yOuR famous racetrack, she recommends that you autobahn, but drifting sideways at 140kph on days), the police will file a report. Your car has www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1pklvKKnd0 don’t have breakfast before you climb into the the ring is completely different.’ to be street legal to enter the ring, but otherwise The Stig vs Sabine Schmitz: passenger seat of her BMW M5 ring taxi. In 2004 she added to her fame count when anything on wheels can (and does) go. www.youtube.com/ pAlms to sweat With a V10 under the hood and 378kW it is she challenged Jeremy Clarkson of Top Gear, From superbikes to sightseeing buses, with watch?v=Q1p0Gg9uLBw&NR=1 definitely the most powerful taxi available for claiming she could beat his lap time of 9min GTRs, GT3s and AMGs thrown in, it’s a Sabine in the BMW Ring Taxi: hire in the world and Sabine is the fastest hack. -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

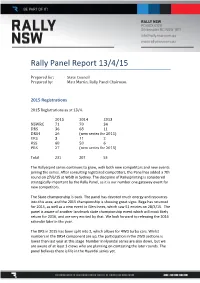

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

Dacia Sandero the Smarter Supermini This Is What an All-Rounder – Looks Like Dacia Sandero

Dacia Sandero The smarter supermini This is what an all-rounder – looks like Dacia Sandero 3 Dacia Sandero A little more about our range Dacia fully supports the introduction of the new emissions testing procedure, called ‘Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure’ (WLTP). WLTP represents a positive change to provide consumers with fuel economy and emissions data which is more representative of the results you may achieve in real life. 5 Be ready for anything Modern life is mad. One day you’re commuting in the city. Next day you’re packing up for a family adventure weekend. Luckily, the Sandero can keep up with your lifestyle like a champ. Its fluid lines, defined curves and honeycomb grille are proof that affordable doesn’t mean dull. While a choice of rigorously-tested engines and surprisingly robust suspension mean it’s equally inspiring behind the wheel. You can also relax with Hill Start Assist, ABS, Electronic Stability Control and front and side airbags, as standard. Everything you need for a smooth and peaceful ride. Fancy chilling out with air conditioning? Or rocking out to your favourite tunes on DAB or your phone using Bluetooth®, Apple CarPlay™ or Android Auto™*? It’s all possible with your Sandero. * Available on vehicles built from December 2018. Compatibility: An iPhone no earlier than iPhone 5 & iOS 7.1, an Anroid 5.0 (Lollipop). Connecting a smartphone to access Apple CarPlay™ or Android Auto™ should only be done when the car is safely parked. Drivers should only use the system when it is safe to do so and in compliance with the requirements of The Highway Code. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

The Chesire Magazine Coolscupting in Anassa 04/03/2020

EARLY SPRING 2020 s ISSUE 073 Back In G A Family FreddieE Flintoff discussesR the new Top Gear series Football We trial Rio Ferdinand’s Football Escapes camp e ut & B a y Is the Ferrari Portofino more than A BEAST just a pretty face? Travel news WORDS:CRAIG HOUGH Hotel Du Cap-Eden-Roc Turns 150 Hidden away at the Southern-most tip of the Cap d’Antibes, the award-winning Hotel du Cap-Eden- Roc is considered one of the most beautiful properties in the world, and certainly the most glamourous place to stay on the French Riviera. Queen Victoria frst visited the French Riviera in 1882, drawn by warmer winters, and took with her a steady stream of English aristocrats, thereby sealing the Riviera’s reputation for years to come. As the iconic hotel celebrates its 150th year in 2020, it takes a look back at its origin as a writers’ retreat for the creatively spirited. Its location was always a place of great beauty and inspiration, which captured the attention of Auguste de Villemessant, the talented founder of Le Figaro, who realised its potential and built the elegant Villa Soleil in 1870 in the heart of what he deemed ‘paradise’. www.oetkercollection.com The Great Garden Escape This spring and summer, celebrate all things Somerset as ‘The Great Garden Escape to The Newt in Somerset’ returns with a host of new experiences and tours. Starting every weekend from 10 April – 27 September, a designated frst-class carriage will take guests from London Paddington to Castle Cary on a scenic journey deep into the West Country to discover the UK’s most exciting country estate and cultivated gardens. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 179 4 April 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price) Channel 4, 7 December 2010, 22:00 5 [see page 37 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues)] Elite Days Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 12:00 to 13:15 Elite TV (Channel 965), 1 December 2010, 13:00 to 14:00 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 8 December 2010, 10.00 to 11:30 Elite Nights Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 22:30 to 23:35 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 6 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:25 Elite TV (Channel 965), 16 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:45 Elite TV (Channel 965), 22 December 2010, 00:50 to 01:20 Elite TV (Channel 965), 4 January 2011, 22:00 to 22:30 13 Page 3 Zing, 8 January 2011, 13:00 27 Deewar: Men of Power Star India Gold, 11 January 2011, 18:00 29 Bridezilla Wedding TV, 11 and 12 January 2011, 18:00 31 Resolved Dancing On Ice ITV1, 23 January 2011, 18:10 33 Not in Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues) Channel 4, 30 November 2010 to 29 December 2010, 22:00 37 [see page 5 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price)] Top Gear BBC2, 30 January 2011, 20:00 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Advertising Scheduling Cases In Breach Breach findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 47 Resolved Resolved findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 49 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Zac Goldsmith MP Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 15 and 16 July 2010 50 Other programmes not in breach 73 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes and licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on the BBC’s Impartiality, Accountability and Integrity BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University International Anglophone Media Studies Laura Kaai 3617602 Simon Cook January 2013 7,771 Words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Framework 4 2.1 The BBC’s Values 4 2.1.2 Impartiality 5 2.1.3 Conflicts of Interest 5 2.1.4 Past Controversy: The Russell Brand Show and the Carol Thatcher Row 6 2.1.5 The Clarkson Controversy 7 2.2 Columns 10 2.3 Media Discourse Analysis 12 2.3.2 Agenda Setting, Decoding, Fairness and Fallacy 13 2.3.3 Bias and Defamation 14 2.3.4 Myth and Stereotype 14 2.3.5 Sensationalism 14 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 15 3.1.2 Procedure 16 3.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 17 3.2.2 Procedure 19 4. Discussion 21 4.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 21 4.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 23 5. Conclusion 26 Works Cited 29 Appendices 35 3 1. Introduction “I’d have them all shot in front of their families” (“Jeremy Clarkson One”). This is part of the comment Jeremy Clarkson made on the 2011 public sector strikes in the UK, and the part that led to the BBC receiving 32,000 complaints. Clarkson said this during the 30 December 2011 live episode of The One Show, causing one of the biggest BBC controversies. The most widely watched factual TV programme in the world, with audiences in 212 territories worldwide, is BBC’s Top Gear (TopGear.com). -

A Second Season of James May's Travelogue Will Film in the U.S. And

A Second Season of James May’s Travelogue Will Film in the U.S. and Launch on Amazon Prime Video Next Year August 26, 2021 James May: Our Man in the USA will be produced by Plum Pictures and New Entity and will launch exclusively on Prime Video in over 240 countries and territories LONDON, UK, 26 August 2021 – Following the success of Our Man in Japan, James May: Our Man in the USA will premiere exclusively on Amazon Prime Video in 2022 in over 240 countries and territories. James will set off on an epic 4,000-mile fact-finding mission across the United States of America; a land of mountains and bayous, skyscrapers and deserts, a collision of a myriad viewpoints, cultures, and lifestyles. Journeying from Cape Cod to Seattle, via New York, Detroit, Nashville, New Orleans, Houston, Santa Fe, Las Vegas, and LA, he’ll put the disappointment of 1776 behind him as he immerses himself completely in the real American way of life to discover its true flavour [sic]. “I’m setting off with two objectives: To go West, like the settlers and prospectors of old, and not get fat on American breakfasts in the process,” said James May. “As a man brought up (raised) on U.S. cop shows and Hollywood films, I still believe that everything in America must be better; from the size of their fridges to the uncanny alignment of their teeth. But is it?” “Exhilarating as James exploring his own kitchen is, we are thrilled to be getting Our Man back on the road for another adventure,” said Dan Grabiner, Head of UK Originals, Amazon Studios.