CEO Preferences and Acquisitions*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Consequences of CEO Reappointments Michael Erkens

Welcome back? Economic consequences of CEO reappointments Michael Erkensa Ying Ganb Hervé Stolowyc aErasmus University Rotterdam, Accounting Research Group, Postbus 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, Netherlands; [email protected] bErasmus University Rotterdam, Accounting Research Group, Postbus 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, Netherlands; [email protected] cHEC Paris, Department of Accounting and Management Control, 1 rue de la Libération, 78351 - Jouy-en-Josas, France; [email protected] This version: December 5, 2014 Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Thomas Jeanjean, Ayse Karaevli, Wayne Landsman, Luc Paugam, Joshua Ronen and David Veenman for helpful comments. We appreciate comments from workshop participants at ESSEC (2015), HEC Paris (2015), NYU (2014) and WHU (2014). Hervé Stolowy is a member of the GREGHEC, CNRS Unit, UMR 2959. He expresses his thanks to HEC Paris (research funding 4F73ASTOLOWH). The authors also acknowledge Clara Boecher, Matthieu Lagarde, Markan Tsurkan, Mario Vaupel, Jiayue Zhou and Katy Zhou for their valuable research assistance. Welcome back? Economic consequences of CEO reappointments Abstract We analyze reappointments of former CEOs of U.S. listed firms over the period 1992 – 2013. For a sample of 117 CEO reappointments, we find that shareholders of these firms experience statistically significant negative stock valuation consequences. Our findings are robust to multiple return measurement windows and alternative definitions of abnormal returns. We also document that market reactions depend on certain executive-specific attributes, such as whether she is the founder of the firm or whether she is also appointed as chairman of the board of directors. Finally, we show that firm performance deteriorates after a former CEO is appointed relative to appointing a non-former CEO. -

Corporate Governance When Founders Are Directors

Corporate Governance When Founders Are Directors The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Li, Feng, and Suraj Srinivasan. "Corporate Governance When Founders Are Directors." Journal of Financial Economics 102, no. 2 (November 2011): 454–469. Published Version 10.2139/ssrn.1014157;http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S0304405X11001462 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:29660922 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Corporate Governance when Founders are Directors Feng Li Ross School of Business University of Michigan Phone: (734) 936-2771 Fax: (734) 936-0282 Email: [email protected] Suraj Srinivasan Harvard Business School Phone: (617) 495 6993 Fax: (617) 496-7363 Email: [email protected] December 2010 Forthcoming: Journal of Financial Economics Abstract: We examine CEO compensation, CEO retention policies, and M&A decisions in firms where founders serve as a director with a non-founder CEO (founder-director firms). We find that founder-director firms offer a different mix of incentives to their CEOs than other firms. Pay for performance sensitivity for non-founder CEOs in founder-director firms is higher and the level of pay is lower than that of other CEOs. CEO turnover sensitivity to firm performance is also significantly higher in founder-director firms compared to non-founder firms. -

Innovation in Founder-Run Firms: Evidence from S&P 500 Md

Innovation in Founder-run Firms: Evidence from S&P 5001 Md Emdadul Islam2 Abstract One important element of a firm’s organizational environment that may influence innovation is whether the CEO of the firm is its founder. Popular perception is that the inherent venturous spirit of the founders creates an environment that fosters innovation. This study investigates whether founder-CEOs are more innovative than non-founder CEOs. Using a sample of S&P 500 firms from 1995-2005 and the NBER patent database for measuring innovation output, the study’s baseline results suggest that founder-CEOs are actually associated with fewer patents (quantity of innovation) and fewer citations (quality of innovations), a finding that is contrary to popular perception. However, to reveal the true picture of the innovativeness of founders, evaluating the effect of innovation output on overall firm valuation is necessary. Thus, the study considers the effect of innovation output on firm valuation and suggests that founder-CEOs add more value by innovation. The market greets the innovation output of founder-run firms more favorably than the innovation output of non-founder-run firms. This value addition holds even after controlling for strategic investments such as R&D. This finding helps to identify a probable channel-innovation that bridges, at least partially, the gap in the literature that shows that there is a ‘founder-premium’ Keywords: Founder-CEO, Innovation, Patents, Citations, R&D JEL classification: G32,G34,O31,O32,O34 1 The author would like to thank Professor Dr. Renée Adams, Commonwealth Bank Chair in Finance at UNSW Business School, UNSW Australia and Dr. -

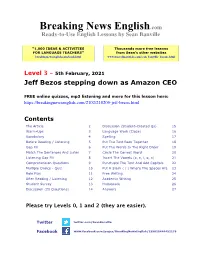

210205-Jeff-Bezos.Pdf

Breaking News English.com Ready-to-Use English Lessons by Sean Banville “1,000 IDEAS & ACTIVITIES Thousands more free lessons FOR LANGUAGE TEACHERS” from Sean's other websites breakingnewsenglish.com/book.html www.freeeslmaterials.com/sean_banville_lessons.html Level 3 - 5th February, 2021 Jeff Bezos stepping down as Amazon CEO FREE online quizzes, mp3 listening and more for this lesson here: https://breakingnewsenglish.com/2102/210205-jeff-bezos.html Contents The Article 2 Discussion (Student-Created Qs) 15 Warm-Ups 3 Language Work (Cloze) 16 Vocabulary 4 Spelling 17 Before Reading / Listening 5 Put The Text Back Together 18 Gap Fill 6 Put The Words In The Right Order 19 Match The Sentences And Listen 7 Circle The Correct Word 20 Listening Gap Fill 8 Insert The Vowels (a, e, i, o, u) 21 Comprehension Questions 9 Punctuate The Text And Add Capitals 22 Multiple Choice - Quiz 10 Put A Slash ( / ) Where The Spaces Are 23 Role Play 11 Free Writing 24 After Reading / Listening 12 Academic Writing 25 Student Survey 13 Homework 26 Discussion (20 Questions) 14 Answers 27 Please try Levels 0, 1 and 2 (they are easier). Twitter twitter.com/SeanBanville Facebook www.facebook.com/pages/BreakingNewsEnglish/155625444452176 THE ARTICLE From https://breakingnewsenglish.com/2102/210205-jeff-bezos.html The founder of Amazon.com, Jeff Bezos, will step down from his role as CEO (Chief Executive Officer). Mr Bezos, 57, announced he will finish as CEO later this year. Instead of being CEO, he will take on the new role of Amazon's executive chair. He will pass on the position of CEO to Andy Jassy. -

How Does the Influence of Founders and Investors Relate to Employee Compensation in Entrepreneurial Firms?

How Does the Influence of Founders and Investors Relate to Employee Compensation in Entrepreneurial Firms? Ola Bengtsson* and John R. M. Hand** First draft: May 2010 This draft: November 2010 Abstract Employment in entrepreneurial firms is often associated with non-pecuniary benefits and access to unique technologies. We provide evidence that these work motivators are higher when the founder has more (and outside investors have less) influence over the firm’s decision-making. In particular, we show that the degree of control exerted by venture capital investors helps explain the design of non- CEO employee compensation contracts. Across 18,935 employee compensation contracts from 1,809 U.S. firms, we find that those with more VC / less founder dominance pay their employees higher cash salaries, provide stronger cash and equity incentives, and have more formal pay policies in place. However, the differences in cash pay and incentives only apply to hired-on employees and not to founders. Founders are special in that they receive similar compensation contracts regardless of the company’s degree of founder/VC dominance. Our results are consistent with the argument that investor control changes the nature of hired-on employment in innovative, high-potential small businesses. We thereby shed new light on how innovative small businesses evolve into professionalized companies, the role that venture capitalists play in this evolution, and the determinants of entrepreneurial compensation. *University of Illinois and ** University of North Carolina. We are grateful to VentureOne and Brendan Hughes for providing the survey data to us, and for valuable comments from workshop participants at Drexel University. -

ARE FOUNDER Ceos MORE OVERCONFIDENT THAN PROFESSIONAL Ceos?

ARE FOUNDER CEOs MORE OVERCONFIDENT THAN PROFESSIONAL CEOs? EVIDENCE FROM S&P 1500 COMPANIES Joon Mahn Lee Krannert School of Management Purdue University 403 W State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907 [email protected] Byoung-Hyoun Hwang 1 Cornell SC Johnson College of Business Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management Cornell University Warren Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853 [email protected] and Korea University Business School Korea University Anam-dong, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, Korea 136-701 Hailiang Chen Department of Information Systems City College of Business University of Hong Kong Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong [email protected] Keywords: Overconfidence, Founder CEOs, Professional CEOs, Corporate Governance 1 All authors contributed equally. Corresponding author: Byoung-Hyoun Hwang, [email protected]. ABSTRACT Research Summary We provide evidence that founder CEOs of large S&P 1500 companies are more overconfident than their non-founder counterparts (“professional CEOs”). We measure overconfidence via CEO tweets, CEO statements during earnings conference calls, management earnings forecasts, and CEO option-exercise behavior. Compared with professional CEOs, founder CEOs use more optimistic language on Twitter and during earnings conference calls. In addition, founder CEOs are more likely to issue earnings forecasts that are too high; they are also more likely to perceive their firms to be undervalued, as implied by their option-exercise behavior. To date, investors appear unaware of this “overconfidence bias” among founders. Managerial Summary: This paper helps to explain why firms managed by founder CEOs behave differently from those managed by professional CEOs. We study a sample of S&P 1500 firms and find strong evidence that founder CEOs are significantly more overconfident than professional CEOs. -

The Effectiveness of CEO Leadership Styles in the Technology Industry

The Effectiveness of CEO Leadership Styles in the Technology Industry Sean Dougherty, Andrew Drake Advisors: Dr. Jonathan Scott and Professor Katherine Nelson Temple University Explanation of research The purpose of this research is to determine the impact of leadership style on financial success. A great deal of research has been done on the factors that affect the financial success of a company, but leadership is one factor that tends to be overlooked. That is due to the nature of leadership; like other aspects of human resources management such as company culture, leadership is not easily quantifiable. In order to study leadership’s effect on company success, we needed to make leadership less abstract and more concrete. We needed a means of distinguishing the way one person leads in comparison to another person, and the solution was presented to us upon reading Primal Leadership. Authors Daniel Goleman, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee make the detailed claim that the way a person leads can always be categorized into at least one of six distinct emotional leadership styles. We seek to build on the research of Goleman, Boyatzis, and McKee by analyzing the effectiveness of each of these styles in terms of driving financial success. To measure financial success, we looked at the behavior of stock price in the time following an initial public offering. For our data set, we chose to study 60 companies in the technology industry that have gone public since the year 2000. With each company, we researched the CEO who led the company during the IPO and assigned him or her one to two leadership styles that he or she exhibits. -

WE STAND for DEMOCRACY. a Government of the People, by the People

A14 EZ RE the washington post . wednesday, april 14, 2021 EZ RE A15 ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT WE STAND FOR DEMOCRACY. A Government of the people, by the people. A beautifully American ideal, but a reality denied to many for much of this nation’s history. As Americans, we know that in our democracy we should not expect to agree on everything. However, regardless of our political affiliations, we believe the very foundation of our electoral process rests upon the ability of each of us to cast our ballots for the candidates of our choice. For American democracy to work for any of us, we must ensure the right to vote for all of us. We all should feel a responsibility to defend the right to vote and to oppose any discriminatory legislation or measures that restrict or prevent any eligible voter from having an equal and fair opportunity to cast a ballot. Voting is the lifeblood of our democracy and we call upon all Americans to join us in taking a nonpartisan stand for this most basic and fundamental right of all Americans. Paid for by: Ursula Burns, Debra Lee, Ken Jacobs, Joel Cutler, David Fialkow, Hemant Taneja, Casey Wasserman, Ken Chenault, Ken Frazier, William Lewis, Clarence Otis, Charles Phillips blackeconomicalliance.org Email: [email protected] Original Signatories Cambridge Associates Individuals Roger Crandall, Chairman, President The founders of Tango Fritz Lanman Kieran O’Reilly & Rory O’Reilly, Daniel Schreiber & Shai Wininger, John Zimmer, Peter Fader, Professor of Marketing,The & Chief Executive Officer, MassMutual Co-founders, Millions cofounders, Lemonade Co-founder & President, Lyft Rodney C. -

Strategic Choices Among Founder and Non-Founder Ceos: an Empirical Investigation

Cho and Abebe Strategic Choices and Founder-CEOs STRATEGIC CHOICES AMONG FOUNDER AND NON-FOUNDER CEOS: AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION Young Sik Cho College of Business Administration, The University of Texas-Pan American 1201 W. University Drive, Edinburg, TX 78539, USA [email protected] Michael A. Abebe College of Business Administration, The University of Texas-Pan American 1201 W. University Drive, Edinburg, TX 78539, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT The literature on founder-CEO influence on firm performance seems to particularly focus on founders’ role at the early stage of venture formation such as initial public offering (IPO). While they obviously play a crucial role in creating organizational identity at the firm’s inception, their role as leaders of larger and older organizations is yet unclear. The purpose of this paper is to empirically examine whether founder-CEO led firms significantly differ from their non-founder counterparts in their strategic choices. We tested our predictions on 111 publicly-traded U.S. manufacturing firms between 1985-2010. The results of our empirical analysis generally indicate that there is indeed a statistically significant difference in the level of merger & acquisition intensity. Keywords: Founder-CEO, Strategic choice, Mergers and acquisitions, Alliances, Strategic leadership INTRODUCTION The influence of top executives on strategic choice and firm performance is an important research area in strategic management. A rich stream of literature exists on why and how top executives shape the strategic direction of the firm (Child, 1972, Miles and Snow, 1978; Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Finklestein and Hambrick, 1996; Carpenter, Geletkanycz and Sanders, 2004). Consistent empirical findings in the area indeed suggest that top executives influence the formulation and execution of strategic decisions and ultimately firm performance (Mintzberg, 1978; Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Boeker, 1997; Henderson, Miller and Hambrick, 2006). -

D– Lessons from Amazon's Endeavor

Technovation xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Technovation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/technovation Transformative direction of R&D– lessons from Amazon's endeavor ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Amazon jumped up to the world's top Research and Development (R&D) firm in 2017. R&D Such a rapid and notable increase in R&D investment has raised the question of a new R&D definition in the Amazon digital economy, which Amazon insists includes both “routine or periodic alterations” (traditionally classified as Transformation non-R&D) and “significant improvement” (classified as R&D), as Amazon transforms the former into thelatter Business model during its R&D process. User-driven innovation A convincing answer to this question will give rise to insightful suggestions regarding a new concept of R&D in the digital economy. 1. Introduction Notwithstanding such an increase in expenses for business activities generally described as R&D, Amazon insists on describing them as There is a crucial dilemma between R&D expansion and pro- “technology and content.” While the former focuses on business activ- ductivity decline in the digital economy, caused by the two-faced ities for “significant improvement,” the latter encompasses those for nature of ICT (Watanabe et al., 2015; Tou et al., 2019). “routine or periodic alterations.” Amazon has invested considerable Notwithstanding the fear of such a dilemma, Amazon has been ac- resources in extremely innovative business areas such as AWS, Kindle, complishing notable performance by rapidly increasing R&D Alexa and Amazon Go for the former improvement. In parallel with (Galloway, 2017), which has raised two questions. -

February 11, 2019 Speaker Nancy Pelosi Leader Charles Schumer

February 11, 2019 Speaker Nancy Pelosi Leader Charles Schumer United States House of Representatives United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20510 Leader Mitch McConnell Leader Kevin McCarthy United States Senate United States House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi, Leader McConnell, Leader Schumer, and Leader McCarthy, The Coalition for the American Dream is an organization of business leaders representing every major sector of the U.S. economy pursuing a bipartisan, permanent legislative solution for Dreamers. Our membership includes more than 100 employers and trade associations spanning a variety of U.S. industries, from retail to manufacturing to tech, that represent more than half of American private sector workers. We write to urge the new Congress to act immediately and pass a bipartisan, permanent legislative solution to enable Dreamers who are currently living, working, and contributing to our communities to continue doing so. With the re-opening of the federal government and the presumptive restart of immigration and border security negotiations, now is the time for Congress to pass a law to provide Dreamers the certainty they need. These are our friends, neighbors, and coworkers, and they should not have to wait for court cases to be decided to determine their fate when Congress can act now. Studies by economists across the ideological spectrum have determined that if Congress fails to act, our economy could lose $350 billion in GDP, and the federal government could lose $90 billion in tax revenue. Thus, continued delay or inaction will cause significant negative economic and social impact to businesses and hundreds of thousands of deserving young people across the country. -

Founder-Ceos and Corporate Social Performance (Csp): a Process Model

Cha and Abebe Founder-CEO and CSP FOUNDER-CEOS AND CORPORATE SOCIAL PERFORMANCE (CSP): A PROCESS MODEL Wonsuk Cha Michael A. Abebe Department of Management, College of Business Administration, The University of Texas-Pan American 1201 West University Drive, Edinburg, Texas 78539 E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected] Telephone: (956)-789-8857, (956)-381-3392 ABSTRACT While the link between top executive characteristics and CSP have been explored, whether and how founder-CEOs influence CSP remains understudied. Besides, it is still unclear as to whether founder-CEOs are more effective in improving their firms’ CSP than non-founder CEOs. To address this gap, we propose a process model on why CEO founder status is positively related to CSP and firm financial performance. We propose that founder-CEOs enhance the level of CSP by emphasizing transformational leadership and long-term orientation in their overall decision- making. We conclude with detailed discussion of the contribution of our theoretical model to future research. Keywords: Founder-CEOs, Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability, Strategic Leadership INTRODUCTION There is a growing understanding among both scholars and practitioners that the ultimate purpose of a publicly-owned business enterprise are not only the maximization of shareholder value but also corporate social performance (CSP). These objectives are intertwined since socially responsible corporate activities have been shown to affect the firm’s reputation (Orlitzky, Schmidt & Rynes, 2007; Brammer & Millington, 2008), customer satisfaction (Lev, Petrovits & Radhakrishnan, 2010) and favorable evaluation by external stakeholders (McGuire, Sundgren & Schneeweis, 1988; Arya & Zhang, 2009). In this study, we adopt the definition of CSP proposed by Wood (1991, p.