A Case Study of Neuro-Autobiographies in the Age Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Experiences of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants Encountering Workplace Incivility

Resilience, Dysfunctional Behavior, and Sensemaking: The Experiences of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants Encountering Workplace Incivility by James P. McGinnis B.S. as Physician Associate, May 1995, The University of Oklahoma MPAS in Emergency Medicine, May 2002, The University of Nebraska A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education May 16, 2021 Dissertation directed by Shaista E. Khilji Professor of Human and Organizational Learning and International Affairs The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University certifies that James Patrick McGinnis, II has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Education as of December 7, 2020. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Resilience, Dysfunctional Behavior, and Sensemaking: The Experiences of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants Encountering Workplace Incivility James P. McGinnis Dissertation Research Committee: Shaista E. Khilji, Professor of Human and Organizational Learning, Dissertation Director Ellen F. Goldman, Professor of Human and Organizational Learning, Committee Member Neal E. Chalofsky, Associate Professor Emeritus, Committee Member ii Dedication To the unheralded Spartans of emergency medicine, themselves committed to the art of healing, who willingly stand in the breech between sickness and health, between life and death, and ultimately between chaos and order. iii Acknowledgement No person stands as an island. Despite our cries of independence, rugged individualism, and self-sufficiency, none of us attain success wholly upon our singular efforts. We are intimately intertwined with those who surround us and the relationships that we encounter throughout our lived experiences. -

Resilience in Health and Illness

Psychiatria Danubina, 2020; Vol. 32, Suppl. 2, pp 226-232 Review © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia RESILIENCE IN HEALTH AND ILLNESS 1,2 3 1,4 2 1 Romana Babiü , Mario Babiü , Pejana Rastoviü , Marina ûurlin , Josip Šimiü , 1 5 Kaja Mandiü & Katica Pavloviü 1Faculty of Health Studies, University of Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina 2Department of Psychiatry, University Clinical Hospital Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina 3Faculty of Science and Education University of Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina 4Department of Surgery, University Clinical Hospital Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina 5Department of Urology, University Clinical Hospital Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina received: 11.4.2020; revised: 24.4.2020; accepted: 2.5.2020 SUMMARY Resilience is a relatively new concept that lacks clarity although it is increasingly used in everyday conversation and across various disciplines. The term was first introduced into psychology and psychiatry from technical sciences and afterwards thorough medicine and healthcare. It represents a complex set of various protective and salutogenic factors and process important for understanding health and illness, and treatment and healing processes. It is defined as a protective factor that makes an individual more resilient to adverse events that lead to positive developmental outcomes. Resilience is a positive adaptation after stressful situations and it represents mechanisms of coping and rising above difficult experiences, i.e., the capacity of a person to successfully adapt to change, resist the negative impact of stressors and avoid occurrence of significant dysfunctions. It represents the ability to return to the previous, so-called "normal" or healthy condition after trauma, accident, tragedy, or illness. In other words, resilience refers to the ability to cope with difficult, stressful and traumatic situations while maintaining or restoring normal functioning. -

How Educators Can Nurture Resilience in High-Risk Children and Their Families

HOW EDUCATORS CAN NURTURE RESILIENCE IN HIGH-RISK CHILDREN AND THEIR FAMILIES Donald Meichenbaum, Ph.D. Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada and Research Director of The Melissa Institute for Violence Prevention and Treatment Miami, Florida www.melissainstitute.org and www.TeachSafeSchools.org University of Waterloo Contact: (Oct. – May) Department of Psychology Donald Meichenbaum Waterloo, Ontario 215 Sand Key Estates Drive Canada N2L 3G1 Clearwater, FL 33767 Phone: (519) 885-1211 ext. 2551 Email: [email protected] Meichenbaum 2 WAYS TO BOLSTER RESILIENCE IN CHILDREN In the aftermath of both natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes), and man-made trauma (e.g., terrorist attacks), educators are confronted with the challenging question of how to help their students and families cope and recover from stressful events. There are lessons to be learned from those children and families who evidence “resilience” in the face of stressful events. To introduce this topic, consider the following question: “Are there any children in your school who, when you first heard of their backgrounds, you had a great deal of concern about them? Now when you see them in the hall, you have a sense of pride that they are part of your school. These children may cause you to wonder, ‘How can that be?’” This question has been posed to educators by one of the founders of the research on resilience in children, Norman Garmezy. It reflects the increasing interest in how children who grow up in challenging circumstances and who have experienced traumatic events “make it” against the odds. -

Measuring Post-Secondary Student Resilience Through the Child & Youth Resilience Measure and the Brief Resilience Scale

Measuring Post-Secondary Student Resilience Through the Child & Youth Resilience Measure and the Brief Resilience Scale by Hany Soliman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Higher Education Graduate Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Hany Soliman 2017 Measuring Post-Secondary Student Resilience Through the Child & Youth Resilience Measure and the Brief Resilience Scale Master of Arts 2017 Hany Soliman Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis examines how the Child & Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-12) and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) measure post-secondary student resilience as viewed by the University of Toronto in Toronto, Canada, which breaks down resilience into competence domains and adaptive resources. Cognitive interviews were conducted to assess item comprehension, with some items causing confusion with students. The two scales were administered in a survey instrument for a sample of 87 second- and third-year undergraduate students. Internal consistency reliability is high for both the CYRM-12 (Cronbach’s alpha = .82) and the BRS (Cronbach’s alpha = .83). Exploratory Factor Analysis yielded a 3-factor solution for the CYRM-12 representing family, friends and community, and a 1-factor solution for the BRS representing the ability to recover from stress. Scores from both scales indicate strengths in motivation and achievement orientation with more variability in familial relations and community belongingness. Limitations include a low response rate. ii Acknowledgments I am both grateful for and humbled by this opportunity to conduct a master’s thesis project. -

The Impact of Family, Community, and Resilience on African-American Young Adults Who Had Parents Incarcerated During Childhood" (2011)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2011 The Impact of Family, Community, and Resilience on African- American Young Adults Who Had Parents Incarcerated During Childhood Marilyn Diana Ming Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Child Psychology Commons, and the Developmental Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Ming, Marilyn Diana, "The Impact of Family, Community, and Resilience on African-American Young Adults Who Had Parents Incarcerated During Childhood" (2011). Dissertations. 583. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/583 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE IMPACT OF FAMILY, COMMUNITY, AND RESILIENCE ON AFRICAN-AMERICAN YOUNG ADULTS WHO HAD PARENTS INCARCERATED DURING CHILDHOOD by Marilyn Diana Ming Chair: Sylvia Gonzalez ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University School of Education Title: THE IMPACT OF FAMILY, COMMUNITY, AND RESILIENCE ON AFRICAN-AMERICAN YOUNG ADULTS WHO HAD PARENTS INCARCERATED DURING CHILDHOOD Name of researcher: Marilyn Diana Ming Name and degree of faculty chair: Sylvia Gonzalez, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2011 Problem Parental incarceration affects millions of children, and their numbers continue to rise. -

Human-Touch-2015.Pdf

The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, PROSE, AND VISUAL ART University of Colorado u Anschutz Medical Campus FRONT COVER artwork April 2010 #5, March 2013 #1, October 2011 #4, from the series Deterioration | DAISY PATTON Digital media BACK COVER artwork Act of Peace | JAMES ENGELN Color digital photograph University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 Layout & Printing The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 Volume 8 u 2015 BOOK LAYOUT / DESIGN EDITORS IN CHIEF: db2 Design Deborah Beebe (art director/principal) Romany Redman 303.898.0345 :: [email protected] Rachel Foster Rivard www.db2design.com Helena Winston PRINTING Light-Speed Color EDITORIAL BOARD: Bill Daley :: 970.622.9600 [email protected] Amanda Brooke Ryan D’Souza This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Anjali Dhurandhar License. To view a summary of this license, please see Lynne Fox http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. To review the license in Leslie Palacios-Helgeson full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. Amisha Singh To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. SUPERVISING EDITORS: * To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. Henry N. Claman Therese Jones © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright 2 3 University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 Contents VOUME 8 u 2015 Preface ............................................................................................................ -

What Julian Saw: the Embodied Showings and the Items for Private Devotion

religions Article What Julian Saw: The Embodied Showings and the Items for Private Devotion Juliana Dresvina History Faculty, University of Oxford, 41-47 George St, Oxford OX1 2BE, UK; [email protected] Received: 28 February 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 2 April 2019 Abstract: The article traces potential visual sources of Julian of Norwich’s (1343–after 1416) Revelations or Showings, suggesting that many of them come from familiar everyday devotional objects such as Psalters, Books of Hours, or rosary beads. It attempts to approach Julian’s text from the perspective of neuromedievalism, combining more familiar textual analysis with some recent findings in clinical psychology and neuroscience. By doing so, the essay emphasizes the embodied nature of Julian’s visions and devotions as opposed to the more apophatic approach expected from a mystic. Keywords: revelations; mysticism; ekphrasis; neuromedievalism; neuroarthistory; psychohistory; Julian of Norwich; visions; sleep paralysis; psalters; books of hours; rosary beads 1. Introduction This paper has a very simple thesis to illustrate: that a lot, if not most of theology, found in the writings of Julian of Norwich (1343–after 1416)—a celebrated mystic and the first English female author known by name—comes from familiar, close-to-home objects and images. Images are such an integral aspect of our existence that the famous neuroscientist Rodolfo Llinás, and many after him, claimed that our brain is about making images (Llinás and Paré 1991; Damasio 2010, pp. 63–88). However, such complicated private visual experiences as dream-visions or mystical revelations are insufficient to synthesise knowledge per se, particularly if understood as aimed at a broader community. -

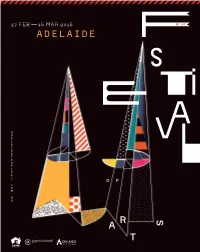

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

Los Angeles Lawyer May 2016

ENTERTAINMENT32nd Annual THE MAGAZINE OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION LAW ISSUE MAY 2016 / $5 LIFE RIGHTS page 24 COPYRIGHT of ARTWORKS page 30 On Direct: Janna Sidley page 8 IP Rights in Bankruptcy page 11 Fairly Simple Los Angeles lawyers Michael C. Donaldson and Lisa A. Callif propose a three-question test for fair use in nonfiction page 16 2016 ENTERTAINMENT LAW ISSUE FEATURES 16 Fairly Simple BY MICHAEL C. DONALDSON AND LISA A. CALLIF While de minimis and statutory four-prong analyses of fair use are certainly to be considered, a three-question test may also apply Plus: Earn MCLE credit. MCLE Test No. 257 appears on page 19. 24 Rights to Life BY LEE S. BRENNER AND CATHY D. LEE The defense of newsworthiness applies to the common law and statutory causes of action for right of publicity 30 Copied in Stone BY MICHAEL D. KUZNETSKY AND MARK D. KESTEN Two recent cases concerning copyright infringement of large-scale sculptures involve complex issues of notice and registration, statute of limitations, and damages Los Angeles Lawyer DEPARTME NTS the magazine of the Los Angeles County 8 On Direct 35 By the Book Bar Association Janna Sidley Narrative of My Captivity among the May 2016 INTERVIEW BY DEBORAH KELLY Sioux Indians REVIEWED BY GREG VICTOROFF Volume 39, No. 3 10 Barristers Tips Steps to take in beginning a new legal 36 Closing Argument COVER PHOTO: TOM KELLER career Finding new perspectives on time to help BY VICTOR ORTIZ improve productivity BY AREZOU KOHAN 11 Practice Tips The disposition of intellectual property licenses in bankruptcy BY MICHAEL V. -

Refugee Children Traumatized by War and Violence: the Challenge Offered to the Service Delivery System

DOCUMENT RESUME 1 ED 326 598 UD 027 845 ; AUTHOR Benjamin, Marva P.; Morgan, Patti C. TITLE' Refugee Children Traumatized by War and Violence: The Challenge Offered to the Service Delivery System. I TnsTITUTION Georgetown Univ. Cnild Development Center, t 3hington, DC. CASSP Technical Assistance Center. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Serwces Administration keHHS/PHS), Rockville, MD. Office for Maternal and Child Health Services.; National Inst. of Mental Health (DHHS), Rockville, MD. Child and Adolescent ' Service System Program. PUB DATE Apr 89 NOTE 61p.; Proceedings of the Conference on Refugee Children Traumatized by War and Violence (2ethesda, MD, Jeptember 28-30, 1988). AVAILABLE FROM CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center, 3800 Reservoir Rd., N.W., Washington, DC 20007. PUB TYPr Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) -- '7..:lected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adjustment (to Environment); Agency Cooperation; *Childhood Needs; *Cooperative Programs; *Cultural Awareness; Educational Needs; Mental HealLn Programs; *Minority Group Children; Models; *Refugses; Urban Programs ABSTRACT This document summarizes issues presented by 16 scholars, researchers, and practitioners from the United States and Canada at a conference on refugee children traumatized by war and 1 violence and suggests a service delivery model for these children and 1 1 their families. A larz,e percentage of the legal and illegal i immigrants who have entered the Uniteu States since the Refugee Act 1 of 198n are children who require assistance from community-based institut:.ons. These children present the following problems to the human services delivery system: (1) lack of a common language; (2) culturally different concepts of illner,s and health; (3) educational deficiencies; and (4) fee- of "foreign" treatment approaches. -

An Investigation of the Resilience of Community College Students with Chronic Physical

An Investigation of the Resilience of Community College Students with Chronic Physical Health Impairments A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Patton College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Mary Beth Held August 2017 © 2017 Mary Beth Held. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled An Investigation of the Resilience of Community College Students with Chronic Physical Health Impairments by MARY BETH HELD has been approved for the Department of Counseling and Higher Education and The Patton College of Education by Peter C. Mather Professor of Counseling and Higher Education Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Patton College of Education 3 Abstract HELD, MARY BETH, Ph.D., August 2017, Higher Education An Investigation of the Resilience of Community College Students with Chronic Physical Health Impairments Director of dissertation: Peter C. Mather One population of students who are commonly overlooked in research but are a significant population attending community colleges is students living with chronic physical impairments (CPIs) such as irritable bowel syndrome, migraine headaches, and diabetes. To address the gap in scholarly research, I utilized an asset-based approach to understand the lived experiences of students who are persisting at one rural community college in Appalachia. My investigation utilized a phenomenological methodology to form descriptive themes. Through purposeful random sampling and snowball sampling, 14 participants living with CPIs who had a minimum GPA of a 2.0 and had completed two or more semesters of college were interviewed. Through in-depth face-to-face interviews lasting 60 to 90 minutes, participants provided rich data. -

Disorders and Emotionalitturbances; Treatment, Needs and Mental Health' Services; and Dissemination and Use of Research Results

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 612 EC 080 036 , AUTHOR Segal, Julius, Ed.; Boomer, Donald S.,-Ed. TITLE Research in the Service of Mental Health: Summary Report of the Research Task Force of the National Institute o4 Mental Mealth. INSTITUTION National Inst. of Mental Health (DHEW), Rockville, Md. REPORT NO DHEW-A'DM -75 -237 PUB DATE 75 NOTE 107p.; For the complete report see EC 080 035 AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Order No. ADM-75-237) EDRS PRICE' MF-$0.76 HC-$5.70 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Alcoholism; Behavior Patterns; Biological Influences; *Emotionally Disturbed; Exceptional Child Education; Information Dissemination; *Mental: Health; Psychological Characteristics; *Psychological SerVices; *Reseaich Reviews (Publications); Social Adjustment; Social Influences; Therapy ABSTRACT Presented,is a summary of the findings and recommendations of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Task Force on Research in the Service of Mental Health. Research is discussed on topics which include background and organization of NIMH research ptograms; biological, psychological, and s0Ekocultural influences on behavior; role and support of basic research; mental illness and behavior disorders; critical developmental periods; alcohol abuse and alcoholism; drug abuse; social problems; mental disorders and emotionalitturbances; treatment, needs and mental health' services; and dissemination and use of research results. Common report themes are noted which are pervasive substantive needs (such as more information on preventive factors), pervasive needs in the interest ofocontinued research (such as improved methodologies), the need to broaden the use of research findings, the need for synthesis and integration, and the need for better_ communication and' coordination.