Handbook of Writing Portfolio Assessment: a Program for College Placement. INSTITUTION Miami Univ., Oxford, OH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grammy Countdown U2, Nelly Furtado Interviews Kedar Massenburg on India.Arie Celine Dion "A New Day Has Come"

February 15, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 781 $6.00 GRAMMY COUNTDOWN U2, NELLY FURTADO INTERVIEWS KEDAR MASSENBURG ON INDIA.ARIE CELINE DION "A NEW DAY HAS COME" The premiere single from "A New Day Has Come," her first new album in two years and her first studio album since "Let's Talk About Love," which sold over 28 million copies worldwide. IMPACTING RADIO NOW 140 million albums sold worldwide 2,000,000+ cumulative radio plays and over 21 billion in combined audience 6X Grammy' winner Winner of an Academy Award for "My Heart Will Go On" Extensive TV and Press to support release: Week of Release Jprah-Entire program dedicated to Celine The View The Today Show CBS This Morning Regis & Kelly Upcoming Celine's CBS Network Special The Tonight Show Kicks off The Today Show Outdoor Concert Series Single produced by Walter Afanasieff and Aldo Nova, with remixes produced by Ric Wake, Humberto Gatica, and Christian B. Video directed by Dave Meyers will debut in early March. Album in stores Tuesday, March 26 www.epicrecords.com www.celinedion.com I fie, "Epic" and Reg. U.S. Pat. & Tm. Off. Marca Registrada./C 2002 Sony Music Entertainment (Canada) Inc. hyVaiee.sa Cartfoi Produccil6y Ro11Fair 1\lixeJyJo.serli Pui3 A'01c1 RDrecfioi: Ron Fair rkia3erneit: deter allot" for PM M #1 Phones WBLI 600 Spins before 2/18 Impact Early Adds: KITS -FM WXKS Y100 KRBV KHTS WWWQ WBLIKZQZ WAKS WNOU TRL WKZL BZ BUZZWORTHY -2( A&M Records Rolling Stone: "Artist To Watch" feature ras February 15, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 781 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher LENNY BEER THE DIVINE MISS POLLY Editor In Chief EpicRecords Group President Polly Anthony is the diva among divas, as Jen- TONI PROFERA Executive Editor nifer Lopez debuts atop the album chart this week. -

SINGLES Be a Coffee Cup

ftL'lLViS: .-.1 l' LllLVLL't'S. sun comes up, even if your best friend S P O T G H T for the remainder of the drowsy day will SINGLES be a coffee cup. The production is taut and vibrant, while Johnson's personali- Edited by Chuck Taylor 11M McGRAW The Cowboy in Me ty- packed vocals infuse the whole affair (3:29) with an appealing energy. It's hard not PRODUCERS: Byron Gallimore,Tim to listen to the song a few times with- POP McGraw, and James Stroud out singing along on the chorus. Looks WRITERS: C. Wiseman, J. Steele, and like the girl has another winner. -DEP JAMIROQUAI You Give Me Something A. Anderson (3:20) PUBLISHERS: BMG Songs /Mrs. PRODUCERS: 1K and the Pope Lumpkin's Poodle, ASCAP, Songs of CHRISTMAS WRITERS: 1K and Smith Windswept /Stairway to Bittner's PUBLISHER: EMI Musk, ASCAP Music /Gottahaveable Music, BMI WILLA FORD Gimme Gimme Gimme Epic 54829 (CD promo) Curb 1643 (CD promo) (3:42) Why Jamiroquai has never been able Recently named the Country Music Atlantic 300712 (CD promo) to repeat the success of its 1997 Assn.'s (CMA) entertainer of the year, breakthrough, Traveling Without Tim McGraw has built a career as one CRACKER Merry Christmas Emily (3:50) Moving, is a profound mystery. of the genre's royalty on the strength Backporch Records 70876 (CD promo) Overseas, JK and company continue JAMES TAYLOR Have Yourself a of consistently great songs. This is BUSH Headful of Ghosts (4:18) to pump out sunny, disco -hued hits Merry Little Christmas (3:26) PRODUCERS: Dave Sardy and Bush PATSY "Kid "Santa Claus/Happy Holly -Day that defy time and trends. -

The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia

The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia by Sandra C Zichermann A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Sociology in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Sandra C Zichermann 2013 The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia Sandra C Zichermann Doctor of Education Sociology in Education University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This thesis investigates the rise of the cultures and music of hip-hop and rap in the West and its effects on its female listeners and fans, especially those in academia. The thesis consists of two parts. First I conducted a content analysis of 95 lyrics from the book, Hip-Hop & Rap: Complete Lyrics for 175 Songs (Spence, 2003). The songs I analyzed were performed by male artists whose lyrics repeated misogynist and sexist messages. Second, I conducted a focus group with young female university students who self-identify as fans of hip-hop and/or rap music. In consultation with my former thesis supervisor, I selected women enrolled in interdisciplinary programmes focused on gender and race because they are equipped with an academic understanding of the potential damage or negative effects of anti-female or negative political messaging in popular music. My study suggests that the impact of hip-hop and rap music on young women is both positive and negative, creating an overarching feeling of complexity for some young female listeners who enjoy music that is infused with some lyrical messages they revile. -

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

ED350616.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 616 CS 213 564 AUTHOR Bertsch, Debbie, Comp.; And Others TITLE The Best of Miami University's Portfolios 1992. INSTITUTION Miami Univ., Oxford, OH. Dept. of English. SPONS AGENCY Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 119p.; For the 1991 edition, see ED 343 509. AVAILABLE FROM Portfolio, Department of English, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056 (free). PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advanced Placement; *College Bound Students; Higher Education; High Schools; High School Students; *Portfolios (Background Materials); Student Placement; *Student Writing Models IDENTIFIERS *Miami University OH; Writing Contexts ABSTRACT This booklet presents seven complete portfolios (each consisting of four pieces of writing) and selections from seven other successful portfolios submitted by 1992 incoming freshmen to Miami University. The portfolios or selections in the booklet were considered to be truly outstanding among the 465 portfolios submitted in 1992. Authors of the portfolios or selections in the booklet received six credits in college composition and completely fulfilled their university writing requirements. The 1992 scoring guide for portfolios, the 1993 description of portfolio contents, the 1993 guidelines for portfolio submission, the 1993 portfolio information form, and a list of the 1992 supervising teachers are attached. (RS) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Offtce of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) his document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating rt O Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality Points of view or opinions stated in this docu . -

D-2 Tupac Shakur Biopic ‘All Eyez on Me’ Receives Mixed Reviews by BRITTANY K

NNPA to Honor Martin Luther King III with 2017 Lifetime Legacy Tupac Shakur Biopic “All Eyez on Award at Annual Conference Me” Receives Mixed Reviews (See page A-4) (See page D-2) SEPTEMBER 17, 2015 VOL.VOL. LXXVV, LXXXI NO. NO49 • 25 $1.00 $1.00 + CA. +CA Sales. Sales Tax Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years YearsThe Voice The Voice of Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for for Itself Itself” THURSDAY THURSDAY,, DECEMBER JUNE 12 22, - 18, 2017 2013 BY SHANNEN HILL Contributing Writer Kia Patterson, 36, is showing her community that hard work pays off. After working in the gro- cery store industry for 17 years, she is now the owner of Grocery Outlet in the city of Compton. Patterson started a training process with Grocery Outlet in June of 2016. After training, she AP FILE gathered her investments Rapper and entrepreneur Dr. Dre and set up a business plan leading her to own the BY KIMBERLEE BUCK the rapper announced a 10 Compton Grocery Outlet Staff Writer million dollar donation on April 1, 2017. toward a performing arts “I made the decision In 1988, one of Black center for Compton High to own a Grocery Outlet America’s most influential School. so that I could have the hip-hop groups, N.W.A. “My goal is to pro- freedom to be able to do let the world know that vide kids with the kind of Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas what I want to do and not they were “Straight Out- tools and learning they de- be pigeon-holed to any- ta Compton.” Over the serve,” Dre said in a state- thing,” said Patterson. -

Mobb Deep Temperature's Rising / Give up the Goods Mp3, Flac, Wma

Mobb Deep Temperature's Rising / Give Up The Goods mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Temperature's Rising / Give Up The Goods Country: US Released: 1995 MP3 version RAR size: 1355 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1290 mb WMA version RAR size: 1774 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 831 Other Formats: DXD XM MP3 MP2 WMA VOX RA Tracklist Hide Credits Temperature's Rising (Remix) A1 4:36 Featuring – Crystal Johnson Temperature's Rising (LP Version) A2 5:00 Co-producer – Mobb DeepFeaturing – Crystal Johnson Give Up The Goods (Just Step) B1 4:03 Featuring – Big Noyd B2 Give Up The Goods (Just Step) (Instrumental) 4:16 Companies, etc. Mastered At – Absolute Audio Credits A&R [Direction] – Matt Life, Schott Free Design – Miguel Rivera Cartel* Executive-Producer – Matt Life, Mobb Deep, Schott Free Management – Sandra "Peachie" Bynum, Tami Cobbs Mastered By – Leon Zervos Mixed By – The Abstract (tracks: A1 to B1), Tony Smalios Photography By – Chi Modu Producer – The Abstract Recorded By – Kenny Ifill* (tracks: B2), Louis Alfred III (tracks: A2), Tim Latham (tracks: B1), Tony Smalios (tracks: A1) Notes Mastered at Absolute Audio, NYC. A2 & B1 taken from the Mobb Deep album "The Infamous". Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 0 7863-64421-1 2 Barcode (Scanned): 078636442112 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Temperature's Rising / RCA 64422-4 Mobb RCA RCA 64422-4 Give Up The Goods US 1995 07863 Deep Records 07863 (Cass, Single) Temperature's Rising / Loud Mobb 07863-64422-2 Give Up The Goods -

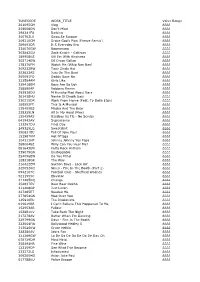

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Using Topic Models to Investigate Depression on Social Media

Using Topic Models to Investigate Depression on Social Media William Armstrong University of Maryland [email protected] Abstract itored during the time between sessions to identify periods of higher depression and subjects that may In this paper we explore the utility of topic- be associated with such periods. For example, if modeling techniques (LDA, sLDA, SNLDA) schoolwork is identified as a troublesome subject in computational linguistic analysis of text for the purpose of psychological evaluation. for the patient the clinician can investigate whether Specifically we hope to be able to identify and homework or grades may be triggering depressive provide insight regarding clinical depression. episodes and propose appropriate actions for such. Furthermore, these tools can scale to larger popu- lations to both identify individuals in need of treat- 1 Introduction ment and discover general trends in depressive be- Topic modeling is a well-known technique in the haviors. field of computational linguistics as a model for re- This paper will explore the utility of three topic ducing dimensionality of a feature space. In addition modeling techniques in these objectives: latent- to being an effective machine-learning tool, reduc- Dirichlet allocation (LDA) in its base form, with su- ing a dataset to a relatively small number of “topics” pervision (sLDA), and with supervision and a nested makes topic models highly interpretable by humans. hierarchy (SNLDA). We will examine the results This positions the technique ideally for problems in of each topic modeling technique qualitatively by which technology and domain experts might work the potential usefulness of their posterior topics to together to achieve superior results. -

Bad Residents Require Medical Attention After Boozey Night

Leeds use VOL-37:15SLX 14' Bad residents require medical Students warned after attention after boozey night sex attacks By Rachel Hunter had or not. drinking...lBut itl is certainly not our guidelines_ We have I steward per 50 By Alex Doorey The night included drinking at six expenence of the event. which we Carnage student customers. as opposed til Leeds bars and concluded at Halo understand involved students drinking for the industry supervision standards. which nightclub, Camages organise nights four 1 I hours. We are aware of several serious are set at I for the first 200 people. Carnage UK, which boasts hosting the to five times each academic year and the incidents arising from the event followed by I per 1(10 customer: After a series of sexual assaults in 'Number One Student Bar Crawl'. has February 4 night was its second in Leeds including...ambultmces being called to thereafter. the city centre. students are to he been sent a letter of complaint from the since September. 1.781 students fmm one of our residences to treat students "We conduct a full risk analysis of reminded of the importance of University following a series of incidents both Leeds University and the Met took who had attended. each event for each individual city. We personal safety. after their latest Leeds event. part. "We are anxious to ensure that there is consider student safety to be of paramount Authorities say that folios% Mg Ambulances were called to Bodington Revellers buy t-shirts online on the no repeat of the problems which arose importance. -

Investigating the Use of Forensic Stylistic and Stylometric Techniques in the Analyses of Authorship on a Publicly Accessible Social Networking Site (Facebook)

INVESTIGATING THE USE OF FORENSIC STYLISTIC AND STYLOMETRIC TECHNIQUES IN THE ANALYSES OF AUTHORSHIP ON A PUBLICLY ACCESSIBLE SOCIAL NETWORKING SITE (FACEBOOK) by COLIN SIMON MICHELL submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject LINGUISTICS at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF EH HUBBARD JULY 2013 I Declaration I declare that “Investigating the use of forensic stylistic and stylometric techniques in the analysis of authorship on a publicly accessible social networking site (Facebook)” is my own work and that all sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. Signature: Colin Simon Michell [Student No: 4322-607-8] II Summary This research study examines the forensic application of a selection of stylistic and stylometric techniques in a simulated authorship attribution case involving texts on the social networking site, Facebook. Eight participants each submitted 2,000 words of self- authored text from their personal Facebook messages, and one of them submitted an extra 2,000 words to act as the ‘disputed text’. The texts were analysed in terms of the first 1,000 words received and then at the 2,000-word level to determine what effect text length has on the effectiveness of the chosen style markers (keywords, function words, most frequently occurring words, punctuation, use of digitally mediated communication features and spelling). It was found that despite accurately identifying the author of the disputed text at the 1,000-word level, the results were not entirely conclusive but at the 2,000-word level the results were more promising, with certain style markers being particularly effective. -

A+ Entertainment Song List by Title

A+ Entertainment Song List by Title Complete Songs listed by TITLE TITLE ARTIST 4 AM Fiona, Melanie 3 Spears, Britney 7 Catfish And The Bottlemen 22 Swift, Taylor 24 Jem 45 Gaslight Anthem 360 Hoge, Josh 679 Fetty Wap & Remy Boyz 1901 Phoenix 1973 Blunt, James 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 7/11 Beyonce #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #Selfie Chainsmokers #Thatpower Will.I.Am & Bieber, Justin (How Could You) Bring Him Home Eamon (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Wanna See You) Push It Baby Paul, Sean & Pretty Ricky (I Wanna See You) Push It Baby Pretty Ricky & Paul, Sean (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Take My) Life Away Default (You Want To) Make A Memory Bon Jovi 0 To 100/The Catch Up Drake 1 Thing Amerie 1, 2 Step (Remix) Ciara & Elliott, Missy 1, 2 Step (Remix) Elliott, Missy & Ciara 1,2 Step Ciara & Elliott, Missy 1,2 Step Elliott, Missy & Ciara 1,2,3,4 Feist 1,2,3,4 Plain White T's 10 Out Of 10 Lou, Louchie & Michie One 10 Out Of 10 Lou, Louchie & Michie One 10 Out Of 10 Michie One & Lou, Louchie 10 Out Of 10 Michie One & Lou, Louchie 100 Girls Stroke 9 100 Years Five For Fighting 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 11 Blocks Wrabel 16 @ War Pasian, Karina 18 Days Saving Abel 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark 19-2000 Gorillaz 19-2000 (Remix) Gorillaz 1st Of Tha Month Bone 2 Become 1 Jewel 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Heads Hell, Coleman 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block 2 Legit To Quit MC Hammer 2 On Tinashe & Schoolboy Q 2 Phones Gates, Kevin 2 Reasons Songz, Trey & T.I.