Chapter 12: the Operational Amplifier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MT-033: Voltage Feedback Op Amp Gain and Bandwidth

MT-033 TUTORIAL Voltage Feedback Op Amp Gain and Bandwidth INTRODUCTION This tutorial examines the common ways to specify op amp gain and bandwidth. It should be noted that this discussion applies to voltage feedback (VFB) op amps—current feedback (CFB) op amps are discussed in a later tutorial (MT-034). OPEN-LOOP GAIN Unlike the ideal op amp, a practical op amp has a finite gain. The open-loop dc gain (usually referred to as AVOL) is the gain of the amplifier without the feedback loop being closed, hence the name “open-loop.” For a precision op amp this gain can be vary high, on the order of 160 dB (100 million) or more. This gain is flat from dc to what is referred to as the dominant pole corner frequency. From there the gain falls off at 6 dB/octave (20 dB/decade). An octave is a doubling in frequency and a decade is ×10 in frequency). If the op amp has a single pole, the open-loop gain will continue to fall at this rate as shown in Figure 1A. A practical op amp will have more than one pole as shown in Figure 1B. The second pole will double the rate at which the open- loop gain falls to 12 dB/octave (40 dB/decade). If the open-loop gain has dropped below 0 dB (unity gain) before it reaches the frequency of the second pole, the op amp will be unconditionally stable at any gain. This will be typically referred to as unity gain stable on the data sheet. -

Loop Stability Compensation Technique for Continuous-Time Common-Mode Feedback Circuits

Loop Stability Compensation Technique for Continuous-Time Common-Mode Feedback Circuits Young-Kyun Cho and Bong Hyuk Park Mobile RF Research Section, Advanced Mobile Communications Research Department Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) Daejeon, Korea Email: [email protected] Abstract—A loop stability compensation technique for continuous-time common-mode feedback (CMFB) circuits is presented. A Miller capacitor and nulling resistor in the compensation network provide a reliable and stable operation of the fully-differential operational amplifier without any performance degradation. The amplifier is designed in a 130 nm CMOS technology, achieves simulated performance of 57 dB open loop DC gain, 1.3-GHz unity-gain frequency and 65° phase margin. Also, the loop gain, bandwidth and phase margin of the CMFB are 51 dB, 27 MHz, and 76°, respectively. Keywords-common-mode feedback, loop stability compensation, continuous-time system, Miller compensation. Fig. 1. Loop stability compensation technique for CMFB circuit. I. INTRODUCTION common-mode signal to the opamp. In Fig. 1, two poles are The differential output amplifiers usually contain common- newly generated from the CMFB loop. A dominant pole is mode feedback (CMFB) circuitry [1, 2]. A CMFB circuit is a introduced at the opamp output and the second pole is located network sensing the common-mode voltage, comparing it with at the VCMFB node. Typically, the location of these poles are a proper reference, and feeding back the correct common-mode very close which deteriorates the loop phase margin (PM) and signal with the purpose to cancel the output common-mode makes the closed loop system unstable. -

Stability Via the Nyquist Diagram Range of Gain for Stability Problem

Stability via the Nyquist diagram Range of gain for stability Problem: For the unity feedback system be- low, where K G(s)= , s(s + 3)(s + 5) find the range of gain, K, for stability, insta- bility and the value of K for marginal stability. For marginal stability, also find the frequency of oscillation. Use the Nyquist criterion. Figure above; Closed-loop unity feedback sys- tem. 1 Solution: K G(jω)= s jω s(s + 3)(s + 5)| → 8Kω j K(15 ω2) = − − · − 64ω3 + ω(15 ω2)2 − When K = 1, 8ω j (15 ω2) G(jω)= − − · − 64ω3 + ω(15 ω2)2 − Important points: Starting point: ω = 0, G(jω)= 0.0356 j − − ∞ Ending point: ω = , G(jω) = 0 270 ∞ 6 − ◦ Real axis crossing: found by setting the imag- inary part of G(jω) as zero, K ω = √15, , j0 {−120 } 2 When K = 1, P = 0, from the Nyquist plot, N is zero, so the system is stable. The real axis crossing K does not encircle [ 1, j0)] −120 − until K = 120. At that point, the system is marginally stable, and the frequency of oscilla- tion is ω = √15 rad/s. Nyquist Diagram Nyquist Diagram 0.05 2 0.04 0.03 1.5 0.02 System: G 1 Real: −0.00824 0.01 Imag: 1e−005 Frequency (rad/sec): −3.91 0.5 0 0 Imaginary Axis −0.01 Imaginary Axis −0.5 −0.02 −1 −0.03 −0.04 −1.5 −0.05 −2 −0.1 −0.08 −0.06 −0.04 −0.02 0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.1 −3 −2.5 −2 −1.5 −1 −0.5 0 Real Axis Real Axis (a) (b) Figure above; Nyquist plots of ( )= K ; G s s(s+3)(s+5) (a) K = 1; (b)K = 120. -

Considerations for Measuring Loop Gain in Power Supplies

Power Supply Design Seminar Considerations for Measuring Loop Gain in Power Supplies Reproduced from 2018 Texas Instruments Power Supply Design Seminar SEM2300, Topic 6 TI Literature Number: SLUP386 © 2018 Texas Instruments Incorporated Power Supply Design Seminar resources are available at: www.ti.com/psds Considerations for Measuring Loop Gain in Power Supplies Manjing Xie ABSTRACT Loop gain measurements show how stable a power supply is and provide insight to improve output transient response. This presentation discusses the theory of open-loop transfer functions and empirical loop gain measurement methods. The presentation then demonstrates how to configure the frequency analyzer and prepare the power supply under test for accurate loop gain measurements. Examples are provided to illustrate proper loop gain measurement techniques. I. INTRODUCTION Figure 2 includes a power stage, the output feedback resistor divider, pulse width modulation Loop gain is the product of all gains around a (PWM) comparator and error amplifier with feedback loop. Figure 1 shows a simple system compensation network. The power stage contains with negative feedback. the power devices, magnetics and capacitors, which V VIN + OUT G(s) transfer energy from the input source to the output. - The output is sensed by the feedback resistor divider. The error amplifier with the compensation network T(s) forms the compensator which amplifies the error between the output feedback (FB) and the reference H(s) voltage, VREF. The output of the compensator, COMP, is modulated by the PWM comparator Figure 1 – Block diagram of a feedback system. which converts COMP, a continuous signal, into a discrete driving signal. When the driving signal is The loop gain of this system is defined as: high, the buck converter low-side MOSFET is T(s)=G(s)⋅ H(s) (1) turned off and high-side MOSFET is turned on. -

" Impedance-Based Stability Analysis for Interconnected Converter

" Impedance-Based Stability Analysis for Interconnected Converter Systems with Open-Loop RHP Poles " Yicheng Liao and Xiongfei Wang This is a preprint of the paper submitted to the IEEE Transaction on Power Electronics. Copyright 2019 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, in any current or future media, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, creating new collective works, for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works. This is a preprint version. The preprint has been submitted to the IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. Impedance-Based Stability Analysis for Interconnected Converter Systems with Open-Loop RHP Poles Yicheng Liao, Student Member, IEEE, Xiongfei Wang, Senior Member, IEEE (Corresponding author: Xiongfei Wang) Abstract – Small-signal instability issues of interconnected converter systems can be addressed by the impedance-based stability analysis method, where the impedance ratio at the point of common connection of different subsystems can be regarded as the open-loop gain, and thus the stability of the system can be predicted by the Nyquist stability criterion. However, the right-half plan (RHP) poles may be present in the impedance ratio, which then prevents the direct use of Nyquist curves for defining stability margins or forbidden regions. To tackle this challenge, this paper proposes a general rule of impedance-based stability analysis with the aid of Bode plots. The method serves as a sufficient and necessary stability condition, and it can be readily used to formulate the impedance specifications graphically for various interconnected converter systems. -

Notes on Gain-Error in Op-Amp Amplifiers This Article Is About the Errors You Can Make in Calculating the Gain of an Op-Amp Amplifier Circuit

Notes On Gain-Error In Op-Amp Amplifiers This article is about the errors you can make in calculating the gain of an op-amp amplifier circuit. I'm assuming here that you are familiar with op-amp amplifier circuits. But let's do a quick review anyway. As you know, the key idea in op-amp circuits is that you start with a very high gain, and then trade off that gain in exchange for increased bandwidth and improved characteristics. What characteristics? You remember; things like input impedance (it gets bigger), output impedance (it gets smaller), distortion (it becomes less), and so forth. Op-amps have enormous open-loop gain . Open-loop gain is the gain of the op-amp chip itself with no feedback. That gain is too big to be used, so you lower it with negative feedback. The gain with feedback is the closed-loop gain . Below are schematics for the two basic feedback circuits: the inverting amplifier and the non-inverting amplifier. The gain equation for each circuit is included. Notice that the gain equations do not include frequency as a variable. Before we get to the punch-line of this article, there's a short story to tell. So, please be patient. Many books either say or imply that the closed-loop gain doesn't change with frequency until the line for ACL meets the line for AOL on the amplifier's Bode plot. What's a Bode plot? C'mon, you remember! It's a graph that shows how the gain of an amplifier "rolls off" as signal frequency increases. -

The Barkhausen Criterion (Observation ?)

View metadata,Downloaded citation and from similar orbit.dtu.dk papers on:at core.ac.uk Dec 17, 2017 brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research Database In Technology The Barkhausen Criterion (Observation ?) Lindberg, Erik Published in: Proceedings of NDES 2010 Publication date: 2010 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Lindberg, E. (2010). The Barkhausen Criterion (Observation ?). In Proceedings of NDES 2010 (pp. 15-18). Dresden, Germany. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 18th IEEE Workshop on Nonlinear Dynamics of Electronic Systems (NDES2010) The Barkhausen Criterion (Observation ?) Erik Lindberg, IEEE Life member Faculty of Electrical Eng. & Electronics, 348 Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark Email: [email protected] Abstract—A discussion of the Barkhausen Criterion which is a necessary but NOT sufficient criterion for steady state oscillations of an electronic circuit. -

Operational Amplifiers and Negative Feedback

Physics 3330 Experiment #4 Fall 2013 Operational Amplifiers and Negative Feedback Purpose This experiment shows how an operational amplifier (op-amp) with negative feedback can be used to make an amplifier with many desirable properties, such as stable gain, high linearity, and low output impedance. You will build both non-inverting and inverting voltage amplifiers using an LF356 op-amp. Introduction The purpose of an amplifier is to increase the voltage level of a signal while preserving as accurately as possible the original waveform. In the physical sciences, transducers are used to convert basic physical quantities into electric signals, as shown in Figure 4.1. An amplifier is usually needed to raise the small transducer voltage to a useful level. DC Power Oscilloscope Temperature, Magnetic Field, Data Radiation, Transducer Amplifier Analysis Acceleration, etc. System Volts to mVolts Volts Figure 4.1 Typical Laboratory Measurement A small voltage or current change at the input of the amplifier controls a much larger signal at the input of whatever circuit or instrument the amplifier’s output is connected to. Measuring and recording equipment typically requires input signals of 1 to 10 V. To meet such needs, a typical laboratory amplifier might have the following characteristics: 1. Predictable and stable gain. The magnitude of the gain is equal to the ratio of the output signal amplitude to the input signal amplitude. 2. Linear amplitude response, so that the output signal is directly proportional to the input signal. Experiment #4 4.1 3. According to the application, the frequency dependence of the gain might be a constant independent of frequency up to the highest frequency component in the input signal (wideband amplifier), or a sharply tuned resonance response if a particular frequency must be picked out. -

Operational Amplifier Gain Stability, Part 1: General System Analysis

Amplifiers: Op Amps Texas Instruments Incorporated Operational amplifier gain stability, Part 1: General system analysis By Miroslav Oljaca, Senior Applications Engineer, and Henry Surtihadi, Analog Design Engineer Introduction In a sinusoidal steady-state analysis, the transfer function The goal of this three-part series of articles is to provide a can be represented as more in-depth understanding of gain error and how it can H( jω= ) H( j ω× ) ej(ϕω ) , (1) be influenced by the actual parameters of an operational amplifier (op amp) in a typical closed-loop configuration. where H( jω ) is the magnitude of the transfer function, This first article explores general feedback control system and ϕ is the phase. Both are functions of frequency. analysis and synthesis as they apply to first-order transfer One way to describe how the magnitude and phase of a functions. This analysis technique is then used to calculate transfer function vary over frequency is to plot them the transfer functions of both noninverting and inverting graphically. Together, the magnitude and phase plots of the op amp circuits. The second article will focus on DC gain transfer function are known as a Bode plot. The magnitude error, which is primarily caused by the finite open-loop part of a Bode diagram plots the expression given by gain of the op amp as well as its temperature dependency. Equation 2 on a linear scale: The third and final article will discuss one of the most H( jω= ) 20 log H( j ω ) (2) dB 10 common mistakes in calculating AC closed-loop gain errors. -

Open Loop Pole Location Bounds for Positive Feedback Operational

Open Loop Pole Location Bounds for Partial Positive Feedback Gain Enhancement Operational Amplifiers Jie Yan, Kee-Chee Tiew, and Randall L. Geiger Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Iowa State University Abstract--For conventional op amps design -Rn open loop poles are usually in the left-half plane. R For amplifiers with negative impedance gain enhancement the open loop pole is adjustable and M1 Vo it can be in the left-half plane or in the right-half plane. In this paper, we justify that it does not Vi require a left-half plane open loop pole for designing a stable close loop amplifier. As a matter of fact, the amplifier exhibits both faster Fig. 1 Conceptual circuit of the negative impedance and more accurate settling when the open-loop compensation technique pole is modestly in the right-half plane. New open loop pole bounds are derived for amplifiers The overall output impedance will change as with adjustable open loop pole to guarantee the value of negative resistor R varies. To stability and to enhance settling time n achieve DC gain enhancement it is necessary to performance. match the negative resistance Rn to the intrinsic resistance Rp at the output node. INTRODUCTION R = R //( 1 / g ) (2) p ds 1 The negative impedance voltage gain The relationship between the value of Rn and enhancement technique, i.e., applying negative the overall dc open loop gain is shown in Fig. 2. impedance at the output of the op amp to cancel its original positive impedance, has been around Av for quite a while [1,2,3,7]. -

Lec 5: Frequency Domain Stability Analysis the Nyquist Criterion

Lec 5: Frequency Domain Stability Analysis The Nyquist Criterion. Stability Margins. Sensitivity November 20, 2018 Lund University, Department of Automatic Control Content 1. Nyquist’s Criterion 2. Stability Margins 3. Sensitivity Function 1 Stability is Important! 2 Stability Margins are also Important! X29 3 Harry Nyquist (1889-1976) Nilsby, Sweden → North Dakota → Yale → Bell Labs • Nyquist’s stability criterion • The Nyquist frequency • Johnson-Nyquist noise 4 Nyquist’s Criterion sin ω0t e(te)(t =) = sin...ω0t Nyquist’s Criterion — A Motivation 2 sin ωt G0 y r = 0 + e(t) 1 −1 With switch in position 2, after transients (G0 stable): e(t) = −|G0(iω)| sin(ωt + arg G0(iω)) = |G0(iω)| sin(ωt + arg G0(iω) + π) Find ω0 such that arg G0(iω0) = −π. Also assume |G0(iω0)| = 1 5 sinsinωω0t e(t) =e(t sin) ω0t Nyquist’s Criterion — A Motivation 2 sin ω0t G0 y r = 0 + e(t) = ... 1 −1 With switch in position 2, after transients (G0 stable): e(t) = −|G0(iω)| sin(ωt + arg G0(iω)) = |G0(iω)| sin(ωt + arg G0(iω) + π) Find ω0 such that arg G0(iω0) = −π. Also assume |G0(iω0)| = 1 5 sinsinωω0t e(te)(t =e)(t = sin) ...ω0t Nyquist’s Criterion — A Motivation 2 sin ω0t G0 y r = 0 + e(t) = sin ω t 0 1 −1 With switch in position 2, after transients (G0 stable): e(t) = −|G0(iω)| sin(ωt + arg G0(iω)) = |G0(iω)| sin(ωt + arg G0(iω) + π) Find ω0 such that arg G0(iω0) = −π. Also assume |G0(iω0)| = 1 5 sinsinωω0t e(te)(t =e)(t = sin) ...ω0t Nyquist’s Criterion — A Motivation 2 sin ω0t G0 y r = 0 + e(t) = sin ω t 0 1 −1 Oscillation will continue in closed loop. -

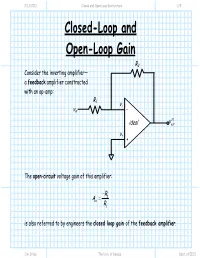

Closed-Loop and Open-Loop Gain

2/13/2011 Closed and Open Loop Gain lecture 1/5 Closed-Loop and Open-Loop Gain R2 Consider the inverting amplifier— a feedback amplifier constructed with an op-amp: R1 v- vin - v oc ideal out v+ + The open-circuit voltage gain of this amplifier: −R2 Avo = R1 is also referred to by engineers the closed loop gain of the feedback amplifier. Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 2/13/2011 Closed and Open Loop Gain lecture 2/5 A closed loop Q: Closed loop? What does that mean? A: The term “closed loop” refers to loop formed by the feed-forward path and the feed-back (i.e., feedback) path of the amplifier. In this case, the feed-forward path is formed by the op-amp, while the feed- back path is formed by the feedback resistor R2. R2 Feed-back Path R1 v- vin - Closed-Loop oc ideal vout v+ + Feed-forward Path Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 2/13/2011 Closed and Open Loop Gain lecture 3/5 An open loop If the loop is broken, then we say the loop is “open”. The gain (vo vi ) for the open loop case is referred to as the open-loop gain. R2 i2 R1 v- Open-Loop vin - oc i1 v ideal out v+ + Jim Stiles The Univ. of Kansas Dept. of EECS 2/13/2011 Closed and Open Loop Gain lecture 4/5 Open and closed loop gains R2 For example, in the circuit we know that: i2 v+ = 0 v oc =−Av v R1 out op ()+− v- vin - ii12==0 oc =− = ideal vout v− viRin 11 0 i1 v+ + Combining, we find the open-loop gain of this amplifier to be: oc vout AAopen= =− op vin Once we “close” the loop, we have an amplifier with a closed-loop gain: oc vout R2 Aclosed = =− vRin 1 which of course is the open-circuit voltage gain of this inverting amplifier.