The Straits of Messina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerey Allen Tucker the Necessity of Models, of Alternatives: Samuel R

Je!rey Allen Tucker The Necessity of Models, of Alternatives: Samuel R. Delany’s Stars in My Pocket like Grains of Sand “Boy loses world, boy meets boy, boy loses boy, boy saves world” In Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction, Damien Broderick provides the %rst thorough analysis of Samuel R. Delany’s last sci- ence %ction novel, Stars in My Pocket like Grains of Sand (1984). He notes that despite—or perhaps, as a result of—its conceptual accomplishments, the novel’s plot is “scant indeed.”& The prologue, “A World Apart,” is set on the planet Rhyonon and tells the story of Rat Korga, an illiterate nineteen-year-old male who undergoes a loboto- mizing procedure known as Radical Anxiety Termination (RAT), after which he is sold to do the menial work and su'er the degradations of a porter at a polar research station. Suddenly, all life on the surface of Rhyonon is eradicated by %re. The mechanics, purpose, and attribution of this planetwide holocaust are never fully explained to the reader; one possibility is that Rhyonon experi- enced a phenomenon called Cultural Fugue that was triggered either locally or by a mysterious and threatening alien race known as the Xlv. Most of the rest of the novel is organized under the title “Monologues” and is narrated by Marq South Atlantic Quarterly 109!2, Spring 2010 "#$ 10.1215/00382876-2009-034 © 2010 Duke University Press 250 Je!rey Allen Tucker Dyeth, an aristocratic “industrial diplomat” whose job frequently requires him to leave his homeworld o( Velm to travel across the galaxy, interact- ing with its myriad peoples and their cultures. -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. -

Futurist Fiction & Fantasy

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Department of English English, Department of September 2006 FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment Gregory E. Rutledge University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Rutledge, Gregory E., "FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY: The Racial Establishment" (2006). Faculty Publications -- Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. C A L L A L O O FUTURIST FICTION & FANTASY The Racial Establishment by Gregory E. Rutledge “I don’t like movies when they don’t have no niggers in ‘em. I went to see, I went to see “Logan’s Run,” right. They had a movie of the future called “Logan’s Run.” Ain’t no niggers in it. I said, well white folks ain’t planning for us to be here. That’s why we gotta make movies. Then we[’ll] be in the pictures.” —Richard Pryor in “Black Hollywood” from Richard Pryor: Bicentennial Nigger (1976) Futurist fiction and fantasy (hereinafter referred to as “FFF”) encompasses a variety of subgenres: hard science fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, sword-and-sorcerer fantasy, and cyberpunk.1 Unfortunately, even though nearly a century has expired since the advent of FFF, Richard Pryor’s observation and a call for action is still viable. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Phallos by Samuel R. Delany ‘Phallos’ by Samuel R

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Phallos by Samuel R. Delany ‘Phallos’ by Samuel R. Delany. The enhanced and revised edition of Samuel Delany’s 2004 novella Phallos , edited by NYU professor of American Studies Robert F. Reid- Pharr, is a provoking book to hold in your hands; what should you expect from a “synopsis of a gay pornographic novella” and what is to be done with “a gay pornographic novella, with the explicit sex omitted”? Who would write such a thing? One does not often find simplification in essays by Berkeley professors, but in “I Can See Atlantis From My House: Sex, Fantasy, and Phallos ” by Darieck Scott, one of the three essays about Phallos appended at the back of the enhanced edition, there is permission to read Phallos in any of the non-literary states of mind that the book provokes. Even if you’re confused, aroused, or off on some fantastically imaginative mind-tangent, Phallos ’s immersive creativity will carry you forward. Scott writes of the possibilities of Phallos , “the novella sprinkles its enchantment by seducing us to dream in the hyperbolic way of the fantasy genre about what might otherwise be dismissed as prosaic or unworthy.” Phallos allows your dreams and your interpretations to flourish—no matter how silly or puerile—under the pretense that they contain “secret wisdom”, a theme in both the novel’s historically-fantastical narrative and its rhetorical ponderings. The actual experience of reading Phallos involves two distinct narrative voices. Voice one, written in the first person, is the voice of a young boy named Neoptolomus. -

The Fall of the Towers by Samuel R. Delany Book

The Fall of the Towers by Samuel R. Delany book Ebook The Fall of the Towers currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Fall of the Towers please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 448 pages+++Publisher:::: Vintage; Reprint edition (February 10, 2004)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 140003132X+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1400031320+++Product Dimensions::::5.2 x 1 x 8 inches++++++ ISBN10 140003132X ISBN13 978-1400031 Download here >> Description: Come and enter Samuel Delany’s tomorow, in this trilogy of high adventure, with acrobats and urchins, criminals and courtiers, fishermen and factory-workers, madmen and mind-readers, dwarves and ducheses, giants and geniuses, merchants and mathematicians, soldiers and scholars, pirates and poets, and a gallery of aliens who fly, crawl, burrow, or swim. Working backwards with Samuel Delany can be an interesting affair, as so much of his later science-fiction (or novels in general) is so infused with theoretical underpinnings that its almost a pleasant revelation that he could write a story without having the plot become hijacked because hes in hurry to get to the essay at the back explaining how everything youve previously read was an exercise in his new literary theory of applied semiotics. Not that his earlier works were devoid of ideas beyond Ray Gun Man fighting Bug Aliens . Babel-17 has to do with the nature of language and Im pretty sure The Einstein Intersection has a rollicking good time with Jungian archetypes, but you can probably argue at some point that he started to trade the entertainment value of a story in exchange for being able to craft it into the delivery system for a series of increasingly abstract ideas (in that light, the novels focusing on sexuality are almost a welcome relief . -

Transgression in Postwar African American Literature Kirin Wachter

Unthinkable, Unprintable, Unspeakable: Transgression in Postwar African American Literature Kirin Wachter-Grene A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Louis Chude-Sokei, Chair Eva Cherniavsky Sonnet Retman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2014 Kirin Wachter-Grene University of Washington Abstract Unthinkable, Unprintable, Unspeakable: Transgression in Postwar African American Literature Kirin Wachter-Grene Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Louis Chude-Sokei English This dissertation argues that African American literary representations of transgression, meaning boundary exploration, reveal a complex relationship between sex, desire, pleasure, race, gender, power, and subjectivity ignored or dismissed in advantageous yet constrained liberatory readings/framings. I trace transgression to confront the critical dismissal of, or lack of engagement with African American literature that does not “fit” ideologically constrained projects, such as the liberatory. The dissertation makes a unique methodological intervention into the fields of African American literary studies, gender and sexuality studies, and cultural history by applying black, queer writer and critic Samuel R. Delany’s conceptualizing of “the unspeakable” to the work of his African American contemporaries such as Iceberg Slim, Octavia Butler, Gayl Jones, Hal Bennett, and Toni Morrison. Delany theorizes the unspeakable as forms of racial and sexual knowing excessive, or unintelligible, to frameworks such as the liberatory. The unspeakable is often represented in scenes of transgressive staged sex that articulate “dangerous” practices of relation, and, as such, is deprived of a political framework through which to be critically engaged. I argue that the unspeakable can be used as an analytic allowing critics to scrutinize how, and why, much postwar African American literature has been critically neglected or flattened. -

Xerox University Microfilms Aoonor*Zmb

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was producad from a microfilm copy of tha original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, tha quality is heavily dependant upon tha quality of tha original submitted. Tha following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tha sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from tha document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing paga(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necanitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You w ill find a good image of the pega in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections w ith a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to tha understanding of the dissertation. -

The Interaction of Feminism(S) and Two Strands of Popular American Fiction, 1968-89

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Kelso, Sylvia (1996) Singularities : the interaction of feminism(s) and two strands of popular American fiction, 1968-89. PhD thesis, James Cook University of North Queensland. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/47036/ If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/47036/ SINGULARITIES: THE INTERACTION OF FEMINISM(S) AND TWO STRANDS OF POPULAR AMERICAN FICTION, 1968-8'9 Thesis submitted by Sylvia Anne KELSO BA (Hons) (Qld) in August 1996 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy i.n the Department of English at James. Cook University of North Queensland STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, lhe undersigned. lhe. aulhor of this tllesis, understand lh.at James Cook University of North Queensland will make it available for use within lhe University Library and. by microfilm or other photographic means. allow access to users in otber approved libraries. All users consulting this chesis will have to sign the following statemem: ·rn consulring 1his 1hesis l agree not m copy or closely paraphrase ii in whole or in pan wichout the written consent of the author; and to ma.ke proper wriuen acknowledgemem for any assiscance I have obtained from it.· Beyond chis. l do not wish to place any restriction of access cm lhis thesis. (signature) (d.ace) ABSTRACT The thesis examines how American writers in the popular genres of Female Gothic, Horror, and Science Fiction interact with strands of (mainly) American feminist thought and action, and with the cultural image of feminism(s) during the period 1968-89. -

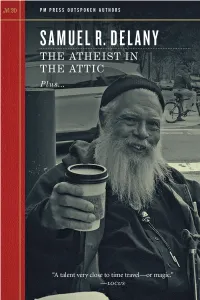

The Atheist in Attic

Samuel R. Delany Science Fiction Hall of Fame SFWA Grand Master Winner of the Hugo Award Nebula Award Locus Award Tiptree Award World Fantasy Award Shirley Jackson Award Stonewall Award Mythopoeic Fantasy Award “I consider Delany not only one of the most important science-fiction writers of the present generation, but a fascinating writer in general who has invented a new style.” —Umberto Eco “The Nevèrÿon series is a major and unclassifiable achievement in contemporary American literature.” —Fredric R. Jameson “The very best ever to come out of the science fiction field. A literary landmark.” —Theodore Sturgeon, on Dhalgren PM PRESS OUTSPOKEN AUTHORS SERIES 1. The Left Left Behind Terry Bisson 2. The Lucky Strike Kim Stanley Robinson 3. The Underbelly Gary Phillips 4. Mammoths of the Great Plains Eleanor Arnason 5. Modem Times 2.0 Michael Moorcock 6. The Wild Girls Ursula K. Le Guin 7. Surfing the Gnarl Rudy Rucker 8. The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Cory Doctorow 9. Report from Planet Midnight Nalo Hopkinson 10. The Human Front Ken MacLeod 11. New Taboos John Shirley 12. The Science of Herself Karen Joy Fowler PM PRESS OUTSPOKEN AUTHORS SERIES 13. Raising Hell Norman Spinrad 14. Patty Hearst & The Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials Paul Krassner 15. My Life, My Body Marge Piercy 16. Gypsy Carter Scholz 17. Miracles Ain’t What They Used to Be Joe R. Lansdale 18. Fire. Elizabeth Hand 19. Totalitopia John Crowley 20. The Atheist in the Attic Samuel R. Delany 21. Thoreau’s Microscope Michael Blumlein 22. The Beatrix Gates Rachel Pollack THE ATHEIST IN THE ATTIC plus “Racism and Science Fiction” and “Discourse in an Older Sense” Outspoken Interview Samuel R. -

Abject Utopianism and Psychic Space: an Exploration of a Psychological Process Toward Utopia in the Work of Samuel R

ABJECT UTOPIANISM AND PSYCHIC SPACE: AN EXPLORATION OF A PSYCHOLOGICAL PROCESS TOWARD UTOPIA IN THE WORK OF SAMUEL R. DELANY AND JULIA KRISTEVA A Dissertation Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada (c) Copyright by Cameron Alexander James Ellis 2014 Cultural Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program September 2014 ABSTRACT Abject Utopianism and Psychic Space: An Exploration of a Psychological Process Toward Utopia in the Work of Samuel R. Delany and Julia Kristeva Cameron Alexander James Ellis This dissertation utilizes the psychoanalytic theories of French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva as a lens through which to read the novels of American author Samuel R. Delany. I argue that concepts proper to Kristeva’s work—namely abjection and/or the abject—can provide a way to think what it might mean to be utopian in the 21st century. Delany’s novels are received historically, which is to say his work speaks from a certain historical and cultural viewpoint that is not that of today; however, I claim that his novels are exceptional for their attempts to portray other ways of being in the world. Delany’s novels, though, contain bodies, psychologies, and sexualities that are considered abject with respect to contemporary morality. Nonetheless, this dissertation argues that such manifestations of abject lived experience provide the groundwork for the possibility of thinking utopianism differently today. Throughout, what I am working toward is a notion that I call Abject Utopianism: Rather than direct attention toward those sites that closely, yet imperfectly, approximate the ideal, one should commit one’s attention to those sights that others avoid, abscond, or turn their nose up at in disgust, for those are the sites of hope for a better world today. -

Lessoning Fiction: Modernist Crisis and the Pedagogy of Form

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2018 Lessoning Fiction: Modernist Crisis and the Pedagogy of Form Matthew Cheney University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Cheney, Matthew, "Lessoning Fiction: Modernist Crisis and the Pedagogy of Form" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 2387. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2387 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LESSONING FICTION: MODERNIST CRISIS AND THE PEDAGOGY OF FORM BY MATTHEW CHENEY B.A., University of New Hampshire, 2001 M.A., Dartmouth College, 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May 2018 ii This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by: Dissertation Director, Robin Hackett, Associate Professor of English Delia Konzett, Professor of English Siobhan Senier, Professor of English Rachel Trubowitz, Professor of English A. Lavelle Porter, Assistant Professor of English New York City College of Technology, City University of New York On 29 March 2018 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v LIST OF FIGURES ix NOTE ON PUNCTUATION AND EDITIONS CITED x ABSTRACT xiv 1. -

Lunacon ’92 March 20 - 22, 1992 the Rye Town Hilton, Rye Brook, New York Progress Report

Lunacon ’92 March 20 - 22, 1992 The Rye Town Hilton, Rye Brook, New York Progress Report Writer Guest of Honor: Samuel R. Delany Artist Guest of Honor: Paul Lehr Fan Guest of Honor: Jon Singer Special Guest: Kristine Kathryn Rusch Featured Filkers: Bill and Brenda Sutton WELCOME Hey, New York - we're baa-ack! After a year of being lost in New England, Lunacon returns to the comfortable surroundings of Westchester County, a short trip north from New York City. Lunacon '92, our 35th annual convention, promises to be our best Lunacon ever. We've spent the last year listening carefully to your comments, criticisms and suggestions and have made many substantial changes. You'll find some familiar things, some new things and some things being done very differently than in the past. We will be working hard, with an eye toward both your enjoyment and convenience. After all, you're the reason Lunacon exists. One of these changes is our new location. We've moved to the luxurious and spacious Rye Town Hilton in Rye Brook, NY The hotel has more space and a better layout to enable us to expand and improve the sort of activities you've come to expect at Lunacon. In addition, the hotel is easily accessible by car and mass transit. If you have any questions, suggestions or comments, please feel free to contact the person running that department or the Lunacon '92 Chair (aka Ghod-Emperor of Lune) at our address listed below. We look forward to seeing you at Lunacon. OUR ADDRESS Please address all correspondence to: Lunacon '92 Post Office Box 338 New York, NY 10150-0338 You can also reach our Chair, Stuart C.