Transgression in Postwar African American Literature Kirin Wachter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Literature As History; History in Literature

MEJO The MELOW Journal of World Literature February 2018 ISSN: Applied For A peer refereed journal published annually by MELOW (The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World) Facts, Distortions and Erasures: Literature as History; History in Literature Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang 1 Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang, Professor of English, Guru Gobind Singh IP University, Delhi Email: [email protected] Editorial Board: Anil Raina, Professor of English, Panjab University Email: [email protected] Debarati Bandyopadhyay, Professor of English, Viswa Bharati, Santiniketan Email: [email protected] Himadri Lahiri, Professor of English, University of Burdwan Email: [email protected] Manju Jaidka, Professor of English, Panjab University Email: [email protected] Neela Sarkar, Associate Professor, New Alipore College, W.B. Email: [email protected] Rimika Singhvi, Associate Professor, IIS University, Jaipur Email: [email protected] Roshan Lal Sharma, Dean and Associate Professor, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala Email: [email protected] 2 EDITORIAL NOTE MEJO, or the MELOW Journal of World Literature, is a peer-refereed Ejournal brought out biannually by MELOW, the Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World. It is a reincarnation of the previous publications brought out in book or printed form by the Society right since its inception in 1998. MELOW is an academic organization, one of the foremost of its kind in India. The members are college and university teachers, scholars and critics interested in literature, particularly in World Literatures. The Organization meets almost every year over an international conference. -

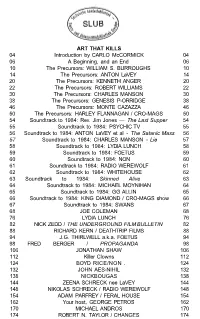

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

The Ethics of Eating Animals in Tudor and Stuart Theaters

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS IN TUDOR AND STUART THEATERS Rob Wakeman, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professors Theresa Coletti and Theodore B. Leinwand Department of English, University of Maryland A pressing challenge for the study of animal ethics in early modern literature is the very breadth of the category “animal,” which occludes the distinct ecological and economic roles of different species. Understanding the significance of deer to a hunter as distinct from the meaning of swine for a London pork vendor requires a historical investigation into humans’ ecological and cultural relationships with individual animals. For the constituents of England’s agricultural networks – shepherds, butchers, fishwives, eaters at tables high and low – animals matter differently. While recent scholarship on food and animal ethics often emphasizes ecological reciprocation, I insist that this mutualism is always out of balance, both across and within species lines. Focusing on drama by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and the anonymous authors of late medieval biblical plays, my research investigates how sixteenth-century theaters use food animals to mediate and negotiate the complexities of a changing meat economy. On the English stage, playwrights use food animals to impress the ethico-political implications of land enclosure, forest emparkment, the search for new fisheries, and air and water pollution from urban slaughterhouses and markets. Concurrent developments in animal husbandry and theatrical production in the period thus led to new ideas about emplacement, embodiment, and the ethics of interspecies interdependence. THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS IN TUDOR AND STUART THEATERS by Rob Wakeman Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Advisory Committee: Professor Theresa Coletti, Co-Chair Professor Theodore B. -

Jerey Allen Tucker the Necessity of Models, of Alternatives: Samuel R

Je!rey Allen Tucker The Necessity of Models, of Alternatives: Samuel R. Delany’s Stars in My Pocket like Grains of Sand “Boy loses world, boy meets boy, boy loses boy, boy saves world” In Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction, Damien Broderick provides the %rst thorough analysis of Samuel R. Delany’s last sci- ence %ction novel, Stars in My Pocket like Grains of Sand (1984). He notes that despite—or perhaps, as a result of—its conceptual accomplishments, the novel’s plot is “scant indeed.”& The prologue, “A World Apart,” is set on the planet Rhyonon and tells the story of Rat Korga, an illiterate nineteen-year-old male who undergoes a loboto- mizing procedure known as Radical Anxiety Termination (RAT), after which he is sold to do the menial work and su'er the degradations of a porter at a polar research station. Suddenly, all life on the surface of Rhyonon is eradicated by %re. The mechanics, purpose, and attribution of this planetwide holocaust are never fully explained to the reader; one possibility is that Rhyonon experi- enced a phenomenon called Cultural Fugue that was triggered either locally or by a mysterious and threatening alien race known as the Xlv. Most of the rest of the novel is organized under the title “Monologues” and is narrated by Marq South Atlantic Quarterly 109!2, Spring 2010 "#$ 10.1215/00382876-2009-034 © 2010 Duke University Press 250 Je!rey Allen Tucker Dyeth, an aristocratic “industrial diplomat” whose job frequently requires him to leave his homeworld o( Velm to travel across the galaxy, interact- ing with its myriad peoples and their cultures. -

Structures of Desire: Postanarchist Kink in the Speculative Fiction Of

Chapter 7 Structures of desire Postanarchist kink in the speculative fiction of Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany Lewis Call It's a beautiful universe ... wondrous and the more exciting because no one has written plays and poems and built sculptures to indicate the structure of desire I negotiate every day as I move about in it. -Samuel Delany, Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand The problem of power is one of the major philosophical and political preoccupations of the modern West. It is a problem which has drawn the attention of some of the greatest minds of the nineteenth and twentieth cen turies, including Fried~ich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault. I have argued else where that the philosophies of power articulated by Nietzsche and Foucault stand as prototypes of an innovative form of anarchist theory, one which finds liberatory potential in the disintegration of the modern self and its liberal humanist politics (Call 2002: chs 1 and 2). Lately this kind of theory has become known as postanarchism. For me, postanarchism refers to a form of contemporary anarchist theory which draws extensively upon postmodern and poststructuralist philosophy in order to push anarchism beyond its traditional boundaries. Postanarchism tries to do this by adding important new ideas to anarchism's traditional critiques of statism and capitalism. Two of these ideas are especially significant for the present essay: the Foucauldian philosophy of power, which sees power as omnipresent but allows us to distinguish between power's various forms, and the Lacanian concept of subjectivity, which understands the self to be constituted by and through its desire. -

A Study of Similarities Between Dalit Literature and African-American Literature

A STUDY OF SIMILARITIES BETWEEN DALIT LITERATURE AND AFRICAN-AMERICAN LITERATURE J. KAVI KALPANA K. SARANYA Ph.D Research Scholars Ph.D Research Scholars Department of English Department of English Presidency College Presidency College Chennai. (TN) INDIA Chennai. (TN) INDIA Dalit literature is the literature which artistically portrays the sorrows, tribulations, slavery degradation, ridicule and poverty endured by Dalits. Dalit literature has a great historical significance. Its form and objective were different from those of the other post-independence literatures. The mobilization of the oppressed and exploited sections of the society- the peasants, Dalits, women and low caste occurred on a large scale in the 1920s and 1930s,under varying leaderships and with varying ideologies. Its presence was noted in India and abroad. On the other hand African American writing primarily focused on the issue of slavery, as indicated by the subgenre of slave narratives. The movement of the African Americans led by Martin Luther King and the activities of black panthers as also the “Little Magazine” movement as the voice of the marginalized proved to be a background trigger for resistance literature of Dalits in India. In this research paper the main objective is to draw similarities between the politics of Caste and Race in Indian Dalit literature and the Black American writing with reference to Bama’s Karukku and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. Keywords: Dalit Literature, African American writings, marginalized, Slave narratives, Black panthers, Untouchable, Exploitation INTRODUCTION In the words of Arjun Dangle, “Dalit literature is one which acquaints people with the caste system and untouchability in India. -

Bgsu1245712232.Pdf (295.66

BODILY BORDERS/NATIONAL BORDERS: TOWARD A POST-NATIONALIST VALUATION OF LIFE IN THE CASE OF KIMBERLY MEDINA-TEJADA Jason Zeh A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Jolie Sheffer, Advisor Kimberly Coates © 2009 Jason Zeh All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Dr Jolie Sheffer, Advisor Drawing upon the theories of Judith Butler, William Godwin, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Michel Foucault, I perform a close reading and textual analysis of a February 24, 2006 court case from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of California entitled “Richardo Medina-Tejada, Plaintiff, v. Sacramento County; Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department; Sheriff Lou Blanas; and Does 1 through XXX, inclusive, Defendants.” In this case, Kimberly (Richardo) Medina-Tejada, a transgender illegal immigrant from Mexico, challenges the constitutionality of her classification by the Sheriff’s Department as a “T-Sep,” or “total separation” inmate, while detained in the Sacramento County Main Jail awaiting deportation. The project explores a particular convergence of nationally specific discourses on race, gender, and citizenship that render Medina-Tejada’s body unintelligible and incapable of being afforded moral worth. I argue that the Nation-State, as a unit of social, political, economic, and cultural organization, is a fragile concept that must be vigorously guarded against threats to its epistemological foundations. This case reveals the State’s profound fear of transgressive modes of embodiment that challenge the categories upon which it is built. As such, Medina-Tejada’s body becomes a site in which the State’s oppression and repression of individual bodies becomes evident. -

Process Summer 2014

PROCESS The alumni newsletter of the Indiana University Department of Anthropology Vitzthum Receives $1.5M NSF Grant to Study Climate Impact in Greenland Virginia Vitzthum is leading an Indi- ana University collaboration with Mon- tana State University and the University of Greenland to conduct a three-year, $1.5 million National Science Foun- dation-funded study of the biological, cultural and environmental challenges facing an Arctic population. Like many coastal and modernizing communities worldwide, northern Greenlanders are confronted by a changing climate, demo- graphic shifts and global economic forces that threaten their continued existence. -CONTINUED ON PAGE 8 Virginia Vitzthum Coastal town in Greenland | Photo by Glenn Mattsing Sept Receives Student focus: PhD Candidate Distinguished Anyur Onur on her field work My doctoral dissertation project, supervised by Prof. Nazif Shahrani Teaching Award and Prof. Sara Friedman, explores the interconnections between mili- tary services, gender equity goals, and pursuit of modernity in Turkey, Jeanne Sept where the society is predominantly Muslim and the political system was named the is secular. I focus on the lives of Turkish -CONTINUED ON PAGE 8 2014 recipient of Anyur Onur the prestigious Frederic Bachman Lieber Memorial Suslak Helps Award. The award, which recognizes Community distinguished teaching and is the Revitalize Ayöök oldest of Indi- Jeanne Sept ana University’s Language teaching awards, was established in 1954 by In the spring, Daniel Suslak Mrs. Katie D. Bachman in memory of her received a $253,000 grant from grandson and was further endowed by Mrs. the National Endowment for the Herman Lieber. Dr Sept was honored at the Humanities to fund his project 2014 Celebration of Distinguished Teaching “Community Directed Audio-Visu- dinner Friday, April 4. -

“Smackdown”: a Textual Analysis of Class, Race and Gender in WWE Televised Professional Wrestling

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Ideological “Smackdown”: A Textual Analysis of Class, Race and Gender in WWE Televised Professional Wrestling Casey Brandon Hart University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Hart, Casey Brandon, "Ideological “Smackdown”: A Textual Analysis of Class, Race and Gender in WWE Televised Professional Wrestling" (2012). Dissertations. 550. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/550 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi IDEOLOGICAL “SMACKDOWN”: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CLASS, RACE AND GENDER IN WWE TELEVISED PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING by Casey Brandon Hart Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT IDEOLOGICAL “SMACKDOWN”: A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CLASS, RACE AND GENDER IN WWE TELEVISED PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING by Casey Brandon Hart May 2012 The focus of this study is an in-depth intertextual examination of how the WWE in 2010 and by extension contemporary professional wrestling in general represents a microcosm of modern cultural ideology. The study examines three major areas in which this occurs. -

New Acquisitions - July 2021

NEW ACQUISITIONS - JULY 2021 BOOKS GENERAL FICTION Call No. Author Title F ACKERMAN, B Ackerman, Brittany, 1989- The Brittanys F ANDREWS, B Andrews, Brian, 1973- Sons of valor F ARNETT, K Arnett, Kristen. With teeth F AUBRAY, C Aubray, Camille The godmothers F BELLEFLEUR, A Bellefleur, Alexandria Hang the moon : a novel F BENEDICT, M Benedict, Marie The personal librarian F BENTLEY, D Bentley, Don Tom Clancy target acquired F BLAU, S Blau, Sarah The Others F BLY, M Bly, Mary, 1962- Lizzie & Dante : a novel F BONVICINI, C Bonvicini, Caterina, 1974- The year of our love F BRENNER, J Brenner, Jamie, 1971- Blush F BRODIE, E Brodie, Emma Songs in Ursa Major F CASTRO, V Castro, V The queen of the cicadas = la reina de las chicharras F CLINTON, B Clinton, Bill, 1946- The president's daughter : a thriller F COLGAN, J Colgan, Jenny Sunrise by the sea F COOLEY, M Cooley, Martha Buy me love F CRONIN, M Cronin, Marianne The one hundred years of Lenni and Margot : a novel F DAILEY, J Dailey, Janet Santa's sweetheart F DIOFEBI, D Diofebi, Dario, 1987- Paradise, Nevada : (this town wasn't built on winners) F DOAN, A Doan, Amy Mason Lady sunshine : a novel F DOREY- STEIN, B Dorey-Stein, Beck Rock the boat : a novel F DUMAS, H Dumas, Henry, 1934-1968 Echo tree : the collected short fiction of Henry Dumas F DUNN, M Dunn, Matt, 1966- Pug actually F EVANS, L Evans, Lissa V for victory : a novel F EVISON, J Evison, Jonathan Legends of the North Cascades F FLANAGAN, R Flanagan, Richard, 1961- The living sea of waking dreams F FOLEY, B Foley, Bridget, 1977- -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M.