Arxiv:1711.02999V3 [Quant-Ph] 31 Jul 2018 Lowing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

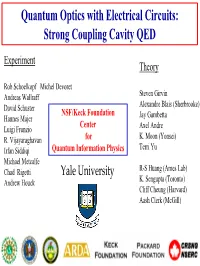

Quantum Optics with Electrical Circuits: Strong Coupling Cavity QED

Quantum Optics with Electrical Circuits: Strong Coupling Cavity QED Experiment Theory Rob Schoelkopf Michel Devoret Andreas Wallraff Steven Girvin Alexandre Blais (Sherbrooke) David Schuster NSF/Keck Foundation Hannes Majer Jay Gambetta Center Luigi Frunzio Axel Andre R. Vijayaraghavan for K. Moon (Yonsei) Irfan Siddiqi Quantum Information Physics Terri Yu Michael Metcalfe Chad Rigetti Yale University R-S Huang (Ames Lab) Andrew Houck K. Sengupta (Toronto) Cliff Cheung (Harvard) Aash Clerk (McGill) 1 A Circuit Analog for Cavity QED 2g = vacuum Rabi freq. κ = cavity decay rate γ = “transverse” decay rate out cm 2.5 λ ~ transmissionL = line “cavity” E B DC + 5 µm 6 GHz in - ++ - 2 Blais et al., Phys. Rev. A 2004 10 µm The Chip for Circuit QED Nb No wires Si attached Al to qubit! Nb First coherent coupling of solid-state qubit to single photon: A. Wallraff, et al., Nature (London) 431, 162 (2004) Theory: Blais et al., Phys. Rev. A 69, 062320 (2004) 3 Advantages of 1d Cavity and Artificial Atom gd= iERMS / Vacuum fields: Transition dipole: mode volume10−63λ de~40,000 a0 ∼ 10dRydberg n=50 ERMS ~ 0.25 V/m cm ide .5 gu 2 ave λ ~ w L = R ≥ λ e abl l c xia coa R λ 5 µm Cooper-pair box “atom” 4 Resonator as Harmonic Oscillator 1122 L r C H =+()LI CV r 22L Φ ≡=LI coordinate flux ˆ † 1 V = momentum voltage Hacavity =+ωr ()a2 ˆ † VV=+RMS ()aa 11ˆ 2 ⎛⎞1 CV00= ⎜⎟ω 22⎝⎠2 ω VV= r ∼ 12− µ RMS 2C 5 The Artificial Atom non-dissipative ⇒ superconducting circuit element non-linear ⇒ Josephson tunnel junction 1nm +n(2e) -n(2e) SUPERCONDUCTING Anharmonic! -

The Quantum Times

TThhee QQuuaannttuumm TTiimmeess APS Topical Group on Quantum Information, Concepts, and Computation autumn 2007 Volume 2, Number 3 Science Without Borders: Quantum Information in Iran This year the first International Iran Conference on Quantum Information (IICQI) – see http://iicqi.sharif.ir/ – was held at Kish Island in Iran 7-10 September 2007. The conference was sponsored by Sharif University of Technology and its affiliate Kish University, which was the local host of the conference, the Institute for Studies in Theoretical Physics and Mathematics (IPM), Hi-Tech Industries Center, Center for International Collaboration, Kish Free Zone Organization (KFZO) and The Center of Excellence In Complex System and Condensed Matter (CSCM). The high level of support was instrumental in supporting numerous foreign participants (one-quarter of the 98 registrants) and also in keeping the costs down for Iranian participants, and having the conference held at Kish Island meant that people from around the world could come without visas. The low cost for Iranians was important in making the Inside… conference a success. In contrast to typical conferences in most …you’ll find statements from of the world, Iranian faculty members and students do not have the candidates running for various much if any grant funding for conferences and travel and posts within our topical group. I therefore paid all or most of their own costs from their own extend my thanks and appreciation personal money, which meant that a low-cost meeting was to the candidates, who were under essential to encourage a high level of participation. On the plus a time-crunch, and Charles Bennett side, the attendees were extraordinarily committed to learning, and the rest of the Nominating discussing, and presenting work far beyond what I am used to at Committee for arranging the slate typical conferences: many participants came to talks prepared of candidates and collecting their and knowledgeable about the speaker's work, and the poster statements for the newsletter. -

Curriculum Vitae Steven M. Girvin

CURRICULUM VITAE STEVEN M. GIRVIN http://girvin.sites.yale.edu/ Mailing address: Courier Delivery: [email protected] Yale Quantum Institute Yale Quantum Institute (203) 432-5082 (office) PO Box 208 334 Suite 436, 17 Hillhouse Ave. (203) 240-7035 (cell) New Haven, CT 06520-8263 New Haven, CT 06511 USA EDUCATION: BS Physics (Magna Cum Laude) Bates College 1971 MS Physics University of Maine 1973 MS Physics Princeton University 1974 Ph.D. Physics Princeton University 1977 Thesis Supervisor: J.J. Hopfield Thesis Subject: Spin-exchange in the x-ray edge problem and many-body effects in the fluorescence spectrum of heavily-doped cadmium sulfide. Postdoctoral Advisor: G. D. Mahan HONORS, AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS: 2017 Hedersdoktor (Honoris Causus Doctorate), Chalmers University of Technology 2007 Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science 2007 Foreign Member, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 2007 Member, Connecticut Academy of Sciences 2007 Oliver E. Buckley Prize of the American Physical Society (with AH MacDonald and JP Eisenstein) 2006 Member, National Academy of Sciences 2005 Eugene Higgins Professorship in Physics, Yale University 2004 Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2003 First recipient of Yale's Conde Award for Teaching Excellence in Physics, Applied Physics and Astronomy 1992 Distinguished Professor, Indiana University 1989 Fellow, American Physical Society 1983 Department of Commerce Bronze Medal for Superior Federal Service 1971{1974 National Science Foundation Graduate Fellow (University of Maine and Princeton University) 1971 Phi Beta Kappa (Bates College) 1968{1971 Charles M. Dana Scholar (Bates College) EMPLOYMENT: 2015-2017 Deputy Provost for Research, Yale University 2007-2015 Deputy Provost for Science and Technology, Yale University 2007 Assoc. -

![Arxiv:1712.05854V1 [Quant-Ph] 15 Dec 2017](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7326/arxiv-1712-05854v1-quant-ph-15-dec-2017-2677326.webp)

Arxiv:1712.05854V1 [Quant-Ph] 15 Dec 2017

Deterministic remote entanglement of superconducting circuits through microwave two-photon transitions P. Campagne-Ibarcq,1, ∗ E. Zalys-Geller, A. Narla, S. Shankar, P. Reinhold, L. Burkhart, C. Axline, W. Pfaff, L. Frunzio, R. J. Schoelkopf,1 and M. H. Devoret1, † 1Department of Applied Physics, Yale University (Dated: December 19, 2017) Large-scale quantum information processing networks will most probably require the entanglement of distant systems that do not interact directly. This can be done by performing entangling gates between standing information carriers, used as memories or local computational resources, and flying ones, acting as quantum buses. We report the deterministic entanglement of two remote transmon qubits by Raman stimulated emission and absorption of a traveling photon wavepacket. We achieve a Bell state fidelity of 73%, well explained by losses in the transmission line and decoherence of each qubit. INTRODUCTION to shuffle information between the nodes of a network. However, the natural emission and absorption temporal envelopes of two identical nodes do not match as one Entanglement, which Schroedinger described as “the is the time-reversed of the other. Following pioneering characteristic trait of quantum mechanics” [1], is instru- work in ion traps [15], many experiments in circuit-QED mental for quantum information science applications have sought to modulate in time the effective coupling such as quantum cryptography and all the known of the emitter to a transmission channel in order to pure-state quantum algorithms [2]. Two systems Alice shape the “pitched” wavepacket [16–20]. Indeed, a rising and Bob that do not interact directly can be entangled if exponential wavepacket could be efficiently absorbed they interact locally with a third traveling system acting [21–24] by the receiver. -

ROBERT J. SCHOELKOPF Yale University

ROBERT J. SCHOELKOPF Yale University Phone: (203) 432-4289 15 Prospect Street, #423 Becton Center Fax: (203) 432-4283 New Haven, CT 06520-8284 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://rsl.yale.edu/ PERSONAL U.S. Citizen. Married, two children. EDUCATION Princeton University, A. B. Physics, cum laude. 1986 California Institute of Technology, Ph.D., Physics. 1995 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Director of Yale Quantum Institute 2014 – present Sterling Professor of Applied Physics and Physics, Yale University 2013- present William A. Norton Professor of Applied Physics and Physics, Yale University 2009-2013 Co-Director of Yale Center for Microelectronic Materials and Structures 2006-2012 Associate Director, Yale Institute for Nanoscience and Quantum Engineering 2009 Professor of Applied Physics and Physics, Yale University 2003-2008 Interim Department Chairman, Applied Physics, Yale University July-December 2012 Visiting Professor, University of New South Wales, Australia March-June 2008 Assistant Professor of Applied Physics and Physics, Yale University July 1998-July 2003 Associate Research Scientist and Lecturer, January 1995-July 1998 Department of Applied Physics, Yale University Graduate Research Assistant, Physics, California Institute of Technology 1988-1994 Electrical/Cryogenic Engineer, Laboratory for High-Energy Astrophysics, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center 1986-1988 HONORS AND AWARDS Connecticut Medal of Science (The Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering) 2017 Elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2016 Elected to National Academy of Sciences 2015 Max Planck Forschungspreis 2014 Fritz London Memorial Prize 2014 John Stewart Bell Prize 2013 Yale Science and Engineering Association (YSEA) Award for Advancement 2010 of Basic and Applied Science Member of Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering 2009 APS Joseph F. -

Quantum Measurement and Bath Engineering for Superconducting Qubits Via Multiple Parametric Couplings

Quantum measurement and bath engineering for superconducting qubits via multiple parametric couplings by Xi Cao Bachelor of Science, Wuhan University, 2014 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Xi Cao It was defended on February 11, 2021 and approved by Michael Hatridge, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh David Pekker, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh Sergey Frolov, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh Ayres Freitas, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh Daniel Lambrecht, Department of Chemistry and Physics, Florida Gulf Coast University Dissertation Director: Michael Hatridge, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Xi Cao 2021 iii Quantum measurement and bath engineering for superconducting qubits via multiple parametric couplings Xi Cao, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 Quantum computers have huge potential applications, but do not currently exist. It has already been proven that a quantum computer would outperform the best classical supercomputers in certain problems, some of which have vital connections with our daily lives. For example, quantum computers efficiently solve the prime number factoring problem, which in turn is the foundation of the RSA algorithm behind most online transactions. There is a great deal of current effort to implement quantum computers, and we have seen good progress in platforms including superconducting circuits, ion traps, and photons in cavity QED systems and spins in semiconductors. -

The 2014 Fritz London Memorial Prize Winners Robert J. Schoelkopf

The 2014 Fritz London Memorial Prize Winners Robert J. Schoelkopf, (Yale University, USA) http://appliedphysics.yale.edu/robert-j-schoelkopf Citation: "The Fritz London Memorial Prize is awarded to Prof. Robert J. Schoelkopf in recognition of fundamental and pioneering experimental advances in quantum control, quantum information processing and quantum optics with superconducting qubits and microwave photons." Robert Schoelkopf is the Sterling Professor of Applied Physics and Physics at Yale University. His research focuses on the development of superconducting devices for quantum information processing, which might eventually lead to revolutionary advances in computing. His group is a leader in the development of solid-state quantum bits (qubits) for quantum computing, and the advancement of their performance to practical levels. Together with his collaborators at Yale, Professors Michel Devoret and Steve Girvin, their team created the new field of “circuit quantum electrodynamics,” which allows quantum information to be distributed by microwave signals on wires. His lab has produced many firsts in the field based on these ideas, including the development of a “quantum bus” for information, and the first demonstrations of quantum algorithms and quantum error correction with integrated circuits. A graduate of Princeton University, Schoelkopf earned his Ph.D. at the California Institute of Technology. From 1986 to 1988 he was an electrical/cryogenic engineer in the Laboratory for High-Energy Astrophysics at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, where he developed low-temperature radiation detectors and cryogenic instrumentation for future space missions. Schoelkopf, who came to Yale as a postdoctoral researcher in 1995, joined the faculty in 1998, becoming a full professor in 2003. -

YALE QUANTUM INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT 2020 on the Cover

YALE QUANTUM INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT 2020 On the cover At first glance the YQI logo seems straightforward, however it contains a few hidden meanings. The Q and I are Director's Word stacked on top of one other to evoke the superposition of state like a on/off button, and the feline-like tail of the Q hints at Schrödinger's cat. But this year, our logo gets atomized! Robert Schoelkopf Sterling Professor of Applied Physics and Physics 1.6 YQI investigator Nir Navon’s group focuses on the quantum many-body 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 role in the next phase of growth in this research, engineering and 1.4 problem. They devised a program known as quantum simulation, in 1.2 teaching activity at Yale. 50 which well-controlled quantum systems can be used to investigate 1 100 0.8 prototypical quantum many-body models. These quantum simulations This year YQI welcomed to our membership six additional faculty 0.6 consists of quantum matter cooled down to “ultracold” scales. members for a 5-year term (see page 11), bringing to 23 the 150 0.4 density Optical 0.2 numbers of faculty members working under the Institute umbrella. 200 0 Ultracold quantum matter is a fascinating platform to conduct this We have broadened our research portfolio by including members x- and y-axis: pixels (1.85 µm/px) (proportional to the number o atoms) program. Researchers can control the laser traps in which the atoms are from the Chemistry department and from areas of physics focused confined, the interactions between particles, or subject them to effective gauge fields. -

The 2014 Fritz London Memorial Prize Winners Michel Devoret

The 2014 Fritz London Memorial Prize Winners Michel Devoret, (Yale University, USA) http://appliedphysics.yale.edu/michel-devoret Citation: "The Fritz London Memorial Prize is awarded to Prof. Michel H. Devoret in recognition of fundamental and pioneering experimental advances in quantum control, quantum information processing and quantum optics with superconducting qubits and microwave photons." Michel Devoret is the F. W. Beinecke Professor of Applied Physics and Physics at Yale University. While completing his electrical engineering studies for the MS degree at Ecole Nationale Superieure des Telecommunications in Paris in 1975, he started graduate work in molecular quantum physics at the University of Orsay. He then joined Professor Anatole Abragam's laboratory in CEA-Saclay for his thesis work on NMR in solid hydrogen, and received his PhD from Paris University in 1982. His two post-doctoral years in Professor John Clarke's laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, were pivotal in his research orientation: working together with then graduate student John Martinis, he discovered the macroscopic level quantization of a Josephson junction, now the basis for superconducting quantum bits. Upon his return at Saclay, he pursued this research on quantum mechanical electronics, starting his own research group with Daniel Esteve and Cristian Urbina. In this new type of electronics, electrical collective degrees of freedom like currents and voltages behave quantum mechanically. Such mesoscopic phenomena underlie the realization of quantum information processing superconducting devices. The main achievements of the "quantronics group" under Michel Devoret's direction are the measurement of the traversal time of tunneling, the invention of the single electron pump, the first observation of the charge of Cooper pairs and the first measurement of the effect of atomic valence on the conductance of a single atom. -

PSEB Working Group

PSEB Working Group Karsten Heeger, PhD (Chair) Karsten Heeger is chair of the physics department, professor of physics, and director of the Wright Laboratory at Yale University. His research focuses on the study of neutrino oscillations and neutrino mass. Prof. Heeger received his undergraduate degree in physics from Oxford University and his Ph.D. from the University of Washington in Seattle where he worked on a model-independent measurement of the solar 8 B neutrino flux in the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO). Before joining the faculty at Yale University he was on the faculty at the University of Wisconsin and a Chamberlain Fellow at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. His work has been recognized with numerous awards including the 2016 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. He is a Fellow of the American Physical Society (APS). At Yale Prof. Heeger has led the renovations and transformation of the Wright Nuclear Structure Laboratory into the new Yale Wright Lab and is building a research program in nuclear, particle, and astrophysics. Prof. Heeger has served on national and international advisory committees including the High Energy Physics Advisory Panel (HEPAP), the Nuclear Science Advisory Committee (NSAC), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and the ASCAC LDRD Independent Review. He has been a member of the DPF Executive Committee, DNP Nominating Committee, DNP NNPSS Steering Committee, and the APS Committee on International Scientific Affairs. Prof. Heeger is Associate Editor for the European Physical Journal C and Journal of Physics G and a reviewer for Physics Review, NIM, Physics Letters, and others. Charles Ahn, PhD Charles H. -

2013 Bell Prize

Short form: "For fundamental and pioneering experiments in entangling superconducting qubits and microwave photons, and their application to quantum information processing." Long form: 2013 Bell prize The third biennial John Stewart Bell Prize for Research on Fundamental Issues in Quantum Mechanics and Their Applications is awarded to Michel Devoret and Robert Schoelkopf, Professors of Applied Physics at Yale University, USA, for fundamental and pioneering experimental advances in entangling superconducting qubits and microwave photons, and their application to quantum information processing. John Bell’s discovery that entanglement had experimentally testable consequences opened a new experimental field in which the boundaries of validity of quantum mechanics would be explored as far as current technology would permit. One new direction was proposed at the beginning of the 80’s by Tony Leggett (recipient of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physics): test the application of quantum mechanics to collective electrical variables of radio-frequency circuits, like macroscopic currents and voltages. In circuits that are purely linear, like an inductance-capacitance (LC) harmonic oscillator, the difference between classical and quantum behavior is very subtle and is hard to observe if one does not introduce a non-linear element. Leggett suggested that a Josephson junction should be used. According to theory, the Josephson effect provides a non-linear inductance which is non-dissipative when the temperature is reduced well below the superconducting gap. Pioneering experiments performed at UC Berkeley in 1983-84 in John Clarke's lab by Devoret and John Martinis demonstrated that a Josephson junction can indeed behave as an artificial atom, possessing quantum energy levels which can be excited by microwave light. -

Basic Concepts in Quantum Information As Well As Provide a Basic Introduction to Circuit QED

February 26, 2013 1:10 World Scientific Review Volume - 9.75in x 6.5in SINGAPORE˙SMG˙FOR˙ARXIV˙2013.02.23 Chapter 1 Basic Concepts in Quantum Information Steven M. Girvin Sloane Physics Laboratory Yale University New Haven, CT 06520-8120 USA [email protected] In the last 25 years a new understanding has evolved of the role of information in quantum mechanics. At the same time there has been tremendous progress in atomic/optical physics and condensed matter physics, and particularly at the interface between these two formerly distinct fields, in developing experimental systems whose quantum states are long-lived and which can be engineered to perform quantum information processing tasks. These lecture notes will present a brief introduction to the basic theoretical concepts behind this ‘second quantum revolution.’ These notes will also provide an introduction to ‘circuit QED.’ In addition to being a novel test bed for non-linear quantum optics of microwave electrical circuits which use superconducting qubits as artificial atoms, circuit QED offers an architecture for constructing quantum information processors. 1. INTRODUCTION and OVERVIEW Quantum mechanics is now more than 85 years old and is one of the most suc- cessful theories in all of physics. With this theory we are able to make remark- arXiv:1302.5842v1 [quant-ph] 23 Feb 2013 ably precise predictions of the outcome of experiments in the microscopic world of atoms, molecules, photons, and elementary particles. Yet despite this success, the subject remains shrouded in mystery because quantum phenomena are highly counter-intuitive to human beings whose intuition is built upon experience in the macroscopic world.