Politico-Ritual Variations on the Assamese Fringes: Do Social Systems Exist? Philippe Ramirez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Candidates for the Post of Specialist Doctors Under NHM, Assam Sl Post Regd

List of candidates for the post of Specialist Doctors under NHM, Assam Sl Post Regd. ID Candidate Name Father Name Address No Specialist NHM/SPLST Dr. Gargee Sushil Chandra C/o-Hari Prasad Sarma, H.No.-10, Vill/Town-Guwahati, P.O.-Zoo 1 (O&G) /0045 Borthakur Borthakur Road, P.S.-Gitanagar, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-Assam, Pin-781024 LATE C/o-SELF, H.No.-1, Vill/Town-TARALI PATH, BAGHORBORI, Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. GOPAL 2 NARENDRA P.O.-PANJABARI, P.S.-DISPUR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State- (O&G) /0002 SARMA NATH SARMA ASSAM, Pin-781037 C/o-Mrs.Mitali Dey, H.No.-31, Vill/Town-Tarunnagar, Byelane No. 2, Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. MIHIR Late Upendra 3 Guwahati-78005, P.O.-Dispur, P.S.-Bhangagarh, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, (O&G) /0059 KUMAR DEY Mohan Dey State-Assam, Pin-781005 C/o-KAUSHIK SARMA, H.No.-FLAT NO : 205, GOKUL VILLA Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. MONTI LATE KIRAN 4 COMPLEX, Vill/Town-ADABARI TINIALI, P.O.-ADABARI, P.S.- (O&G) /0022 SAHA SAHA ADABARI, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781012 DR. C/o-DR. SANKHADHAR BARUA, H.No.-5C, MANIK NAGAR, Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. RINA 5 SANKHADHAR Vill/Town-R. G. BARUAH ROAD, GUWAHATI, P.O.-DISPUR, P.S.- (O&G) /0046 BARUA BARUA DISPUR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781005 C/o-ANUPAMA PALACE, PURBANCHAL HOUSING, H.No.-FLAT DR. TAPAN BANKIM Specialist NHM/SPLST NO. 421, Vill/Town-LACHITNAGAR FOURTH BYE LANE, P.O.- 6 KUMAR CHANDRA (O&G) /0047 ULUBARI, P.S.-PALTANBAZAR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State- BHOWMICK BHOWMICK ASSAM, Pin-781007 JUBAT C/o-Dr. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Lz-^ P-,^-=O.,U-- 15 15 No

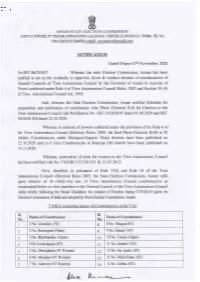

ASSAM STATE ELECTION COMMISSION ADITYA TOWER, 2}TD FI.,OO& DO\AAITO\^AI, G.S. ROAD DISPUR, GUWAHATI -781W. PTT. NO. M1263210/ 2264920 email - [email protected] NOTIFICATION Dated Dispur 17m November,2020 No.SEC.86l2020l7 : Whereas, the state Election Commission, Assam has been notified to act as the Authority to supervise, direct & conduct election of constituencies of General Councils of Tiwa Autonomous Council by the Governor of Assam in exercise of Power conferred under Rule 4 of Tiwa Autonomous Council Rules, 2005 and Section 50 (4) of Tiwa Autonomous Council Act, 1995; And, whereas, the State Election Commission, Assam notified Schedule for preparation and publication of constituency wise Photo Electoral Roll for Election to the Tiwa Autonomous Council vide Notification No. 5EC.5412020147 dated 01 .09.2020 and SEC 5 4 I 2020 I | 0 4 dated 22.1 0 .2020 ; Whereas, in exercise of powers conferred under the provision of the Rule 4 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council (Election) Rules, 2005, the final Photo Electoral Rolls in 30 (thirty) Constituencies under MorigaonA.lagaonl Hojai districts have been published on 22.10.2020 and in 6 (six) Constituencies in Kamrup (M) district have been published on t5.rr.2020; Whereas, reservation of seats for women in the Tiwa Autonomous Council has been notified vide No. TAD/BC/I5712015151 dt.21.07.2015; Now, therefore, in pursuance of Rule 17(I) and Rule 18 of the Tiwa Autonomous Council (Election) Rules 2005, the State Election Commission, Assam calls upon electors of 36 (thirfy-six) nos. of Tiwa Autonomous Council constituencies as enumerated below to elect members to the General Council of the Tiwa Autonomous Council while sfictly following the Broad Guidelines for conduct of Election dwing COVID-l9 given by Election Commission of India and adopted by State Election Commissioq Assam TABLE consistins names of Constituencies of the TAC sl. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Socio-Economic Significances of the Festivals of the Tiwas and the the Assamese Hindus of Middle Assam

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 5 May 2020 | ISSN: 2320-28820 SOCIO-ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCES OF THE FESTIVALS OF THE TIWAS AND THE THE ASSAMESE HINDUS OF MIDDLE ASSAM Abstract:- The Tiwas of Mongoloid group migrated to Assam and scattered into different parts of Nagaon, Morigaon and Karbi Anglong districts and settled with the Assamese Hindus as an inseparable part of their society. The Festivals observed by the Tiwas and the Assamese caste Hindus have their distinct identity and tradition. The festivals celebrated by these communities are both of seasonal and calenderic and some festivals celebrated time to time. Bihu is the greatest festival of the region and the Tiwas celebrate it with a slight variation. The Gosain Uliuwa Mela, Jonbeel Mela and the Barat festival are some specific festivals. Influence of Neo-Vaisnative culture is diffusively and widely seen in the festivals of the plain Tiwas and the other Assamese caste Hindus. The Committee Bhaona festival of Ankiya drama performance celebrated in Charaibahi area is a unique one. This paper is an attempt to look into the socio-economic significances of the festivals of the Tiwas and Assamese Hindus of Middle Assam. Key Words:- Bihu, Gosain Uliuwn, Bhaona. 1. Introduction : In the valley of the mighty river Brahmaputra in Assam, different groups of people of different ethnicity, culture, religion and following various customs and traditions began to live from the very ancient times. Some of them were autochthonous while others came across the Northern or the Eastern hill from the plains on the west as traders or pilgrims. -

Traditional Socio-Political Institutions of the Tiwas

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 4, Ver. II (Apr. 2016) PP 01-05 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Traditional Socio-Political Institutions of the Tiwas Lakhinanda Bordoloi Department of Political Science, Dhing College, Nagaon, Assam I. Introduction The Tiwas are concentrated mainly in the central plains of Assam covering the district of Nagaon, Morigaon and Kamrup. A section of the Tiwas lives in the hilly areas of Karbi Anglong, some villages are in the districts like Jorhat, Lakhimpur and Dhemaji of the state of Assam of and Ri-bhoi district of eastern part of the state of Meghalaya. The Tiwas, other than hills, foothill and some remote/isolated areas don‟t know to speak in their own language. A rapid cultural change has been observed among the Tiwas living in the plains. It is also revealed that, the process of social change occurred in traditional socio-cultural practices in a unique direction and places have formed sub-culture. In the areas- Amri and Duar Amla Mauza of Karbi Anglong, Mayong parts in the state of Meghalaya, villages of foothill areas like Amsoi, Silsang, Nellie, Jagiroad, Dimoria, Kathiatoli, Kaki (Khanggi); the villages like Theregaon near Howraghat, Ghilani, Bhaksong Mindaimari etc are known for the existence of Tiwa language, culture and tradition. In the Pasorajya and Satorajya, where the plain Tiwas are concentrating become the losing ground of traditional socio-political, cultural institutions, practices and the way of life. The King and the Council of Ministers: Before the advent of Britishers the Tiwas had principalities that enjoyed sovereign political powers in the area. -

Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution in Three Tribal Societies of North East India

NESRC Peace Studies Series–4 Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution in Three Tribal Societies of North East India Editor Alphonsus D’Souza North Eastern Social Research Centre Guwahati 2011 Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Alphonsus D’Souza / 1 Traditional Methods of Conflict Management among the Dimasa Padmini Langthasa / 5 The Karbi Community and Conflicts Sunil Terang Dili / 32 Traditional Methods of Conflict Resolution Adopted by the Lotha Naga Tribe Blank Yanlumo Ezung / 64 2 TRADITIONAL METHODS OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION INTRODUCTION 3 system rather than an adversarial and punitive system. inter-tribal conflicts were resolved through In a criminal case, the goal is to heal and restore the negotiations and compromises so that peaceful victim’s well-being, and to help the offender to save relations could be restored. face and to regain dignity. In a civil case, the parties In the case of internal conflicts, all the three involved are helped to solve the dispute in a way communities adopted very similar, if not identical, that there are no losers, but all are winners. The mechanisms, methods and procedures. The elders ultimate aim is to restore personal and communal played a leading role. The parties involved were given harmony. ample opportunities to express their grievances and The three essays presented here deal with the to present their case. Witnesses were examined and traditional methods of conflict resolution practised cross examined. In extreme cases when evidence was in three tribal communities in the Northeast. These not very clear, supernatural powers were invoked communities have many features in common. All the through oaths. The final verdict was given by the elders three communities have their traditional habitat, in such a way that the guilty were punished, injustices distinctive social organisation and culture. -

Polities and Ethnicities in North-East India Philippe Ramirez

Margins and borders: polities and ethnicities in North-East India Philippe Ramirez To cite this version: Philippe Ramirez. Margins and borders: polities and ethnicities in North-East India. Joëlle Smadja. Territorial Changes and Territorial Restructurings in the Himalayas, Adroit, 2013, 978-8187393016. hal-01382599 HAL Id: hal-01382599 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382599 Submitted on 17 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Margins and borders: polities and ethnicities in North-East India1 Philippe RAMIREZ in Joëlle Smadja (ed.) Territorial Changes and Territorial Restructurings in the Himalayas. Delhi, 2013 under press. FINAL DRAFT, not to be quoted. Both the affirmative action policies of the Indian State and the demands of ethno- nationalist movements contribute to the ethnicization of territories, a process which began in colonial times. The division on an ethnic basis of the former province of Assam into States and Autonomous Districts2 has multiplied the internal borders and radically redefined the political balance between local communities. Indeed, cultural norms have been and are being imposed on these new territories for the sake of the inseparability of identity, culture and ancestral realms. -

An Introduction to the Sattra Culture of Assam: Belief, Change in Tradition

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 12 (2): 21–47 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2018-0009 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SATTRA CULT URE OF ASSAM: BELIEF, CHANGE IN TRADITION AND CURRENT ENTANGLEMENT BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In 16th-century Assam, Srimanta Sankaradeva (1449–1568) introduced a move- ment known as eka sarana nama dharma – a religion devoted to one God (Vishnu or Krishna). The focus of the movement was to introduce a new form of Vaishnava doctrine, dedicated to the reformation of society and to the abolition of practices such as animal sacrifice, goddess worship, and discrimination based on caste or religion. A new institutional order was conceptualised by Sankaradeva at that time for the betterment of human wellbeing, which was given shape by his chief dis- ciple Madhavadeva. This came to be known as Sattra, a monastery-like religious and socio-cultural institution. Several Sattras were established by the disciples of Sankaradeva following his demise. Even though all Sattras derive from the broad tradition of Sankaradeva’s ideology, there is nevertheless some theological seg- mentation among different sects, and the manner of performing rituals differs from Sattra to Sattra. In this paper, my aim is to discuss the origin and subsequent transformations of Sattra as an institution. The article will also reflect upon the implication of traditions and of the process of traditionalisation in the context of Sattra culture. I will examine the power relations in Sattras: the influence of exter- nal forces and the support of locals to the Sattra authorities. -

Tribal Politics in Assam: from Line System to Language Problem

Social Change and Development Vol. XVI No.1, 2019 Tribal Politics in Assam: From line system to language problem Juri Baruah* Abstract Colonial geography of Northeast India reveals the fragmentation of the hills and plains and how it shaped the tribal politics in the region. Assam is a unique space to study the struggle of tribal against the mainstream political confront as it is the last frontier of the subcontinent with a distinctiveness of ethnic mosaic. The tribal politics in the state became organised through the self determination of tribal middle class in terms of indignity. The question on indignity is based on land and language which are the strong determinants in the political climate of Assam. This paper tries to argue on the significance of the line system and how it was initially used to create the space for organised tribal politics in terms of land rights. From line system to landlessness the tribal politics is going through different phases of challenges and possibilities by including the demands for autonomy and idea of homeland. The Ethnic identity is indeed directly linked with the region’s unique linguistic nature that becomes fragile in terms of identity questions. 1. Introduction The discourse of ‘tribal politics’ was first used by the colonial rulers in Assam which carries various socio-political backgrounds in the history of Northeast in general and Assam in particular. It became a question of identity in the late colonial Assam originating from the meaning of ‘tribe’ to the representation of ‘indigenous people’. The tribal politics began to challenge the hegemony of caste Hindus in the beginning and then transformed to tribal autonomy in the post-colonial period. -

Land, People and Politics: Contest Over Tribal Land in Northeast India

Land, People and Politics Land, PeoPLe and PoLitics: contest oveR tRibaL Land in noRtheast india Editors Walter Fernandes sanjay BarBora North Eastern Social Research Centre International Workgroup for Indigenous Affairs 2008 Land, People and Politics: contest over tribal Land in northeast india Editors: Walter Fernandes and Sanjay Barbora Pages: 178 ISSN: 0105-4503 ISBN: 9788791563409 Language: English Index : 1. Indigenous peoples; 2. Land alienation; Acknowledgements 3. Northeast India; 4. Colonialism Geographical area: Asia Publication date: January 2009 cover design: Kazimuddin Ahmed, Panos South Asia This book is an outcome of collaboration between North Eastern Social Research Centre (NESRC), Panos South Asia and International Published by: North Eastern Social Research Centre 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA). It is based on studies on Guwahati 781004 land alienation in different states of the Northeast done by a group of Assam, India researchers in 2005-2006. Some papers that were produced during that Tel. (+91-361) 2602819 study are included in this book while others are new and were written Email: [email protected] Website: www.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/ or revised for this publication. We are grateful to all the researchers for NESRC the hard work they have put into these papers. The study, as well as the book, was funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) Denmark. The study was coordinated by Artax Shimray. We are grateful Classensgade 11E DK-2100 Copenhagen to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark for financial support for this Denmark book. We are grateful to IWGIA particularly Christian Erni and Christina www.iwgia.org Nilsson for their support. -

The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596

The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596 1 The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596 Edited by Dr. Anjan Saikia Cinnamara College Publication 2 The Mirror (Vol-3) ISSN – 2348-9596 The Mirror Vol-III: A Bilingual Annual Journal of Department of History, Cinnamara College in collaboration with Assam State Archive, Guwahati, edited by Dr. Anjan Saikia, Principal, Cinnamara College, published by Cinnamara College Publication, Kavyakshetra, Cinnamara, Jorhat-8 (Assam). International Advisor Dr. Olivier Chiron Bordeaux III University, France Chief Advisor Dr. Arun Bandopadhyay Nurul Hassan Professor of History University of Calcutta, West Bengal Advisors Prof. Ananda Saikia Indrajit Kumar Barua Founder Principal President, Governing Body Cinnamara College Cinnamara College Dr. Om Prakash Dr. Girish Baruah School of Policy Sciences Ex-Professor, DKD College National Law University, Jodhpur Dergaon, Assam Dr. Daljit Singh Dr. Yogambar Singh Farswan Department of Punjab Historical Deparment of History & Archaeology Studies Punjabi University, Patiala H.N. Bahuguna Garhwal University Dr. Ramchandra Prasad Yadav Dr. Vasudev Badiger Associate Professor, Satyawati Professor, and Department of studies College University of Delhi in Ancient History & Archaeology Dr. Rupam Saikia, Director Kannada University, Karnataka College Development Council Dr. Rup Kumar Barman Dibrugarh University Professor, Department of History Dr. K. Mavali Rajan Jadavpur University, West Bengal Department of Ancient Indian Dr. Suresh Chand History Culture & Archeology Special Officer & Deputy Registrar copyrights Santiniketan Incharge-ISBN Agency Dr. Rahul Raj Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Ancient Indian Government of India, New Delhi History Culture & Archaeology Dr. Devendra Kumar Singh Banaras Hindu University Department of History Dr. Uma Shanker Singh Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Department of History Madhya Pradesh Dyal Singh College Dr.