Distribution of Sources of Household Air Pollution: a Cross-Sectional Study in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Central Domain of the Cameroon North Equatorial Fold Belt): PT Data

JOURNAL OF THE CAMEROON ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Vol. 8 No. 2/3 (2009) Neoproterozoic metamorphic events in the kekem area (central domain of the Cameroon north equatorial fold belt): P-T data. TCHAPTCHET TCHATO D.c, NZENTI P. a, NJIOSSEU E. L.a, NGNOTUE, T.b, GANNO S.a a Laboratory of Structural Geology and Petrology of Orogenic Domains (LPGS), Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, P.O.Box 812, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon. b Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, University of Dschang, Cameroon. c Laboratoire d’analyse des matériaux (MIPROMALO), B.P. 2396 Yaoundé. ABSTRACT The Kekem area (southwestern part of the central domain of the Cameroon North Equatorial Fold Belt) is composed of high-grade migmatitic gneisses in which two lithological units are distinguished: (i) a metasedimentary unit (garnet- sillimanite-biotite-gneisses and garnet-biotite-gneisses) interpreted as a continental series; and (ii) meta-igneous rocks comprising mafic pyroxene gneisses, amphibolites, and orthogneisses. These units recrystallised under HT-MP conditions (T=700-800°C, P ≥ 0.5-0.8GPa) and were deformed in relation to a major tangential tectonic event with the NNE-SSW kinematic direction. The lithological association and its tectono-metamorphic evolution show striking similarities with the Banyo and Maham III gneisses, suggesting that the extensional depositional environment envisaged for this formation can be extended farther west. P-T calculations in this contribution provide new data on the Pan-African structural and metamorphic evolution of the metapelites and metabasites in the basement of the Kekem area. The results show two distinct events: (1) crystallization during a Pan-African high temperature metamorphic event and, (2) subsequent deformation and high temperature mylonitization. -

Traditions and Bamiléké Cultural Rites: Tourist Stakes and Sustainability

PRESENT ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, VOL. 7, no. 1, 2013 TRADITIONS AND BAMILÉKÉ CULTURAL RITES: TOURIST STAKES AND SUSTAINABILITY Njombissie Petcheu Igor Casimir1 , Groza Octavian2 Tchindjang Mesmin 3, Bongadzem Carine Sushuu4 Keywords: Bamiléké region, tourist resources, ecotourism, coordinated development Abstract. According to the World Travel Tourism Council, tourism is the first income-generating activity in the world. This activity provides opportunities for export and development in many emerging countries, thus contributing to 5.751 trillion dollars into the global economy. In 2010, tourism contributed up to 9.45% of the world GDP. This trend will continue for the next 10 years and tourism will be the leading source of employment in the world. While many African countries (Morocco, Gabon etc.) are parties to benefit from this growth, Cameroon, despite its huge touristic potential, seems ill-equipped to take advantage of this alternative activity. In Cameroon, tourism is growing slowly and is little known by the local communities which depend on agro-pastoral resources. The Bamiléké of Cameroon is an example faced with this situation. Nowadays in this region located in the western highlands of Cameroon, villages rich in natural, traditional or socio-cultural resources, are less affected by tourist traffic. This is probably due to the fact that tourism in Cameroon is sinking deeper and deeper into a slump, with the degradation of heritages, reception facilities and the lack of planning. In this country known as "Africa in miniature", tourism has remained locked in certain areas (northern part), although the tourist sites of Cameroon are not as limited as one may imagine. -

Dschang Western Cameroon

logy & eo G G e f o o p l h a y n s r i c u Benammi et al., J Geol Geophys 2017, 6:2 s o J Journal of Geology & Geophysics DOI: 10.4172/2381-8719.1000282 ISSN: 2381-8719 Research Article Open Access Preliminary Magnetostratigraphic and Isotopic Dating of the Ngwa Formation (Dschang Western Cameroon) Benammi M1*, Hell JV2, Bessong M2, Nolla D2, Solé J3 and Brunet M1,4 1Institut de Paléoprimatologie, Paléontologie Humaine: Évolution et Paléoenvironnements (IPHEP), UMR-CNRS 7262, Bâtiment B35, 6 rue Michel.Brunet, 86022 Poitiers Cedex, France 2Institut de Recherches Géologiques et Minières du Cameroun, BP 4140, Yaoundé, Cameroun 3Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología Dept. de Geoquímica Cd. Universitaria, Coyoacán 04510 México DF 4Collège de France, Chaire de Paléontologie humaine, 11 Place Marecelin Berthelot, 75231 Paris cedex 05 Abstract A magnetostratigraphic study has been carried out to constrain the age of the volcano-sedimentary Ngwa formation in the eastern part of the Dschang region. A stratigraphic section of about 80 meters thick corresponding to 26 sites has been sampled, and it is composed mainly of fine-grained sandstones, clays, lignite, volcanic sediment and tuffs. A magnetic study conducted on 56 samples shows one or two components of magnetization carried either by titanomagnetite, magnetite and Fe-sulphide. The section that was sampled shows one normal polarity and one reversed polarity. In the lower part of the section, a K-Ar radiometric dating was performed on the plagioclase minerals isolated from the tuffs level situated about 15 meters above the lignite seam, and gave an age of 20.1 ± 0.7 Ma. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 March 2021

CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 572 313 669 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 386 198 818 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 2 Strategic developments 204 1 1 Protests 131 2 2 Methodology 3 Riots 63 28 38 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 43 14 62 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1399 556 1590 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Bamileke Bamileke Language & Culture in the Unitedstates

STUDYING BAMILEKE BAMILEKE LANGUAGE & CULTURE IN THE UNITEDSTATES Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Graffi Please contact the National African Language languages, whose attachment to the Bantu division is still Resource Center, or check the NALRC disputed. While some consider it as a Bantu or a semi-Bantu website at http://www.nalrc.indiana.edu/ language, others prefer to in-clude Bamileke in the Niger-Congo group. Bamileke is not an unique language. It seems that Bamileke Medumba stems from ancient Egyptian and is a root language for many other Bamileke variants. The Bamiléké languages, which are tonal, belong to the Grasslands Bantu Group of the Broad Bantu languages. Nearly every Bamileke kindom names its own dialect as a separate language. Bamiléké languages are not al-ways mutually intelligible between bordering kingdoms. The Bamileke are renowned for their skilled craftsmenship. Bamileke are particularly celebrated carvers in wood, ivory, and horn. Chief’s compounds are notable for their intricately carved door frames and columns. Much of the art produced by the Bamileke tribes are associated with NATIONAL AFRICAN royal ceremonies. Beadwork and masks are common in this LANGUAGE RESOURCE tribe. Even the king may put on a mask for an appearance at a CENTER (NALRC) Kuosi celebration which is a public dance held every other year as a display of the kingdom’s wealth. Bamileke of 701 Eigenmann Hall, 1900 E. 10th St. Bloomington, IN 47406 USA Cameroon raise their dead to the rank of ancestors, worthy BAMILEKE TRADITIONAL ATTIRE T: (812) 856 4199 | F: (812) 856 4189 of worship and sacrifice. -

Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon During the First World War

Soldiers of their Own: Honor, Violence, Resistance and Conscription in Colonial Cameroon during the First World War by George Ndakwena Njung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolph (Butch) Ware III, Chair Professor Joshua Cole Associate Professor Michelle R. Moyd, Indiana University Professor Martin Murray © George Ndakwena Njung 2016 Dedication My mom, Fientih Kuoh, who never went to school; My wife, Esther; My kids, Kelsy, Michelle and George Jr. ii Acknowledgments When in the fall of 2011 I started the doctoral program in history at Michigan, I had a personal commitment and determination to finish in five years. I wanted to accomplish in reality a dream that began since 1995 when I first set foot in a university classroom for my undergraduate studies. I have met and interacted with many people along this journey, and without the support and collaboration of these individuals, my dream would be in abeyance. Of course, I can write ten pages here and still not be able to acknowledge all those individuals who are an integral part of my success story. But, the disservice of trying to acknowledge everybody and end up omitting some names is greater than the one of electing to acknowledge only a few by name. Those whose names are omitted must forgive my short memory and parsimony with words and names. To begin with, Professors Emmanuel Konde, Nicodemus Awasom, Drs Canute Ngwa, Mbu Ettangondop (deceased), wrote me outstanding references for my Ph.D. -

Trijsteeship Council

UN rr E D N A TI O N S Distr. TRIJSTEESHIP GENERAL T/PET.5/1351 COUNCIL 5 November 1958 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: FRENCH FIFTY-THREE PETITIONS COliTAINING COMPLAillTS RELATING TO ,VARIOUS REPRESSIVE MEASURES IN TEE CAJ.\ffi:RCONS UNDER FRENCH ADMI!USTRATION · (Circulated in accordance with paragraph 5 of the annex to resolution 1713 .(XX)) 1. The authors of these fifty-three petitions protest strongly against the provocative acts, brutality, vexations and measures of repression of all kinds of which the Cruneroonians in the Bandleke, }.fu.ngo, Nyong-et-Sanaga, Sanaga-Maritime and Wouri Regions are still said ·to be the victims. The date~ given on the petitions are spread over the period 11 August to 4 October 1958. Forty of the petitions were sent from the Cemeroons under British administration, ten from France, one from Tunisia, one from Berlin and one from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Thirty-one ·or the petitions say that they are members of a local committee of ONE Kamerun, two of them members of committees of the Union des Populations du Cam.eroun, one of them a member of UDEFEC, nine of them members of a group of "Femmes Kameruna.ises"; eigh~ of. them write as individuals) one as a member of an Association ml1t,u0lle and another on behalf of the International Conference of Asian-African Writers. The following extracts describing specific incidents in support of the petitioners' allegations are taken from the original of each of the petitions and are grouped according to the region to which they refer. 2. -

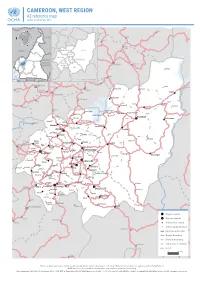

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 Reference Map Update of September 2018

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 reference map Update of September 2018 Nwa Ndu Benakuma CHAD WUM Nkor Tatum NIGERIA BAMBOUTOS NOUN FUNDONGMIFI MENOUA Elak NKOUNG-KHI CENTRAL H.-P. Njinikom AFRICAN HAUT- KUMBO Mbiame REPUBLIC -NKAM Belo NDÉ Manda Njikwa EQ. Bafut Jakiri GUINEA H.-P. : HAUTS--PLATEAUX GABON CONGO MBENGWI Babessi Nkwen Koula Koutoukpi Mabouo NDOP Andek Mankon Magba BAMENDA Bangourain Balikumbat Bali Foyet Manki II Bangambi Mahoua Batibo Santa Njimom Menfoung Koumengba Koupa Matapit Bamenyam Kouhouat Ngon Njitapon Kourom Kombou FOUMBAN Mévobo Malantouen Balepo Bamendjing Wabane Bagam Babadjou Galim Bati Bafemgha Kouoptamo Bamesso MBOUDA Koutaba Nzindong Batcham Banefo Bangang Bapi Matoufa Alou Fongo- Mancha Baleng -Tongo Bamougoum Foumbot FONTEM Bafou Nkong- Fongo- -Zem -Ndeng Penka- Bansoa BAFOUSSAM -Michel DSCHANG Momo Fotetsa Malânden Tessé Fossang Massangam Batchoum Bamendjou Fondonéra Fokoué BANDJOUN BAHAM Fombap Fomopéa Demdeng Singam Ngwatta Mokot Batié Bayangam Santchou Balé Fondanti Bandja Bangang Fokam Bamengui Mboébo Bangou Ndounko Baboate Balambo Balembo Banka Bamena Maloung Bana Melong Kekem Bapoungué BAFANG BANGANGTÉ Bankondji Batcha Mayakoue Banwa Bakou Bakong Fondjanti Bassamba Komako Koba Bazou Baré Boutcha- Fopwanga Bandounga -Fongam Magna NKONGSAMBA Ndobian Tonga Deuk Region capital Ebone Division capital Nkondjock Manjo Subdivision capital Other populated place Ndikiniméki InternationalBAF borderIA Region boundary DivisionKiiki boundary Nitoukou Subdivision boundary Road Ombessa Bokito Yingui The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. NOTE: In places, the subdivision boundaries may suffer of significant inacurracy. Date of update: 23/09/2018 ● Sources: NGA, OSM, WFP ● Projection: WGS84 Web Mercator ● Scale: 1 / 650 000 (on A3) ● Availlable online on www.humanitarianresponse.info ● www.ocha.un.org. -

Further Reading PARROT L

mep Laurent - Bologne:mep.DB 29/05/09 17:53 Page 1 Horticulture and city supply in Africa: evidence from South-West Cameroon RBAN growth in the West African coastal growth poles provides economies Laurent Parrot of scale and the urbanization process leads to agricultural transformation, Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche especially in terms of agricultural intensification. In this context, horticulture is Agronomique pour le Développement particularly well suited for an urban environment and for city supplies. (CIRAD), 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5, France Horticulture benefits from intensification techniques on small areas of Tel.: (334) 67-61-75-02 — fax: (334)-67-61-56-88 land and it provides good revenues for small scale farming systems. E-mail address: [email protected] NIGER NDJAMENA 0 200 km A Maroua I R E G I N Garoua MethodMuea was surveyed in August 1995 and again in June 2004 using Muea market and the main trade independent surveys. The surveys included a complete census of Ngaoundéré routes in Cameroon households (all houses and households were recorded for a random Oku Banso Bamenda Bali NdopFoumban Mamfe Mbouda CENTRAL selection), a household survey (300) and a market survey. Due to their Dschang Foumbot AFRICAN Bafoussam REPUBLIC nature and scope, the household and market surveys provided Muea Douala YAOUNDE Limbe complementary and cross-checked information. MALABO Edea EQUAT. GABON CONGO GUINEA Livestock & Food supplies Food supply Food & Manufacture supplies Main areas of demand Manufacture & Textile supplies Main trade flows Main paved roads The study of market flows among local food markets can be a good indicator of nationwide trade flows. -

Bamileke Businessmen in the Realm of Political Transition in Bamileke Region of Cameroon, 1990- 2000

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume III, Issue II, February 2019|ISSN 2454-6186 Bamileke Businessmen in the Realm of Political Transition in Bamileke Region of Cameroon, 1990- 2000 Nzeucheu Pascal1, Prof. Simon Tata Ngenge2 1History Department, Faculty of Arts, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon 2Vice Dean, Faculty of Law and Political Science, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon Abstract:-In the Bamilike County of Cameroon the businessmen the party in power, CPDM or for the newly created parties prior to the 1990s were not interested in party politics. After andto obtain representative positions.2 In this perspective, independence they were not interested in politics and business and politic became inseparable. Hence, how the concentrated in building wealth. The creation of a monolithic political transition occurred in the Bamileke area? What were systemon 1st September 1966, made it that they were simple the professional and political identifications of the Bamileke militants of the political system and went about doing their businesses successfully. The re-emergence of multi-party Businessmen that stepped in politics during this period? How democracy in 1990 changed the perception of the businessmen and why businessmen participated in local electoral toward political participation. To protect their businesses most of competitions? Finally what was the impact of this them became militants of Cameroon Democratic Movement participation on the reconfiguration of the Bamileke society? (CPDM) in their various home towns in order to preserve their These are some issues raised in the course of this paper. businesses while other defected from CPDM to join the opposition or created their own political parties. -

Commune De Baham

Centre Technique de la Forêt Communale Association des Communes Forestières du Cameroun BP 15 107 Yaoundé CAMEROUN Tél. : (00237) 22 20 35 12 Email : ctfccameroun@ yahoo.com Site web : www.foretcommunale-cameroun.org COMMUNE DE BAHAM RESERVE FORESTIERE DE THEGNE-BAHAM RAPPORT D’ENQUETE SOCIO-ECONOMIQUE DES VILLAGES RIVERAINS A LA RESERVE FORESTIERE (Baghom, Baho,Djegheu, Ngougoua et Chengne) JUILLET 2013 Centre Technique de la Forêt Communale Association des Communes Forestières du Cameroun BP 15 107 Yaoundé CAMEROUN Tél. : (00237) 22 20 35 12 Email : ctfccameroun@ yahoo.com Site web : www.foretcommunale-cameroun.org SOMMAIRE Liste des tableaux..............................................................................................................................................4 Liste des cartes..................................................................................................................................................4 CHAPITRE 1 : INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................5 1.1 Contexte et justification ........................................................................................................................5 1.2 Objectifs de l’étude.....................................................................................................................................6 Objectif global ..............................................................................................................................................6