In Saguaro National Park: Re-Survey of a One-Square-Mile Section First Surveyed in 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Civic Health Index About the Partners

GEORGIA CIVIC HEALTH INDEX ABOUT THE PARTNERS NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CITIZENSHIP GEORGIA FAMILY CONNECTION PARTNERSHIP At the National Conference on Citizenship (NCoC), we believe *HRUJLD)DPLO\&RQQHFWLRQ3DUWQHUVKLS *D)&3 ZRUNVWRDFKLHYH everyone has the power to make a difference in how their community D*HRUJLDZKHUHDOOFKLOGUHQDUHKHDOWK\UHDG\WRVWDUWVFKRRODQG and country thrive. GRZHOOZKHQWKH\JHWWKHUHDQGZKHUHHYHU\IDPLO\LVVWDEOHDQG VHOIVXIÀFLHQW $V D QRQSURÀW SXEOLFSULYDWH LQWHUPHGLDU\ *D)&3 :HDUHDG\QDPLFQRQSDUWLVDQQRQSURÀWZRUNLQJDWWKHIRUHIURQW H[LVWV WR XQLI\ SXEOLF DQG SULYDWH RUJDQL]DWLRQV· FRPPLWPHQW WR of our nation’s civic life. We continuously explore what shapes *HRUJLD·VFKLOGUHQDQGIDPLOLHVPDNHVXUHWKHLUHIIRUWVWRLPSURYH WRGD\·VFLWL]HQU\GHÀQHWKHHYROYLQJUROHRIWKHLQGLYLGXDOLQRXU WKHOLYHVRIFKLOGUHQDQGIDPLOLHVZRUNDQGSURWHFWHYHU\GLPHRI GHPRFUDF\ DQG XQFRYHU ZD\V WR PRWLYDWH JUHDWHU SDUWLFLSDWLRQ WKHLULQYHVWPHQWLQ*HRUJLD·VIXWXUH 7KURXJK RXU HYHQWV UHVHDUFK DQG UHSRUWV 1&R& H[SDQGV RXU QDWLRQ·V FRQWHPSRUDU\ XQGHUVWDQGLQJ RI ZKDW LW PHDQV WR EH D *D)&3ZDQWVWRKHOSEXLOGFRPPXQLWLHVZKHUHFKLOGUHQDQGIDPLOLHV FLWL]HQ:HVHHNQHZLGHDVDQGDSSURDFKHVIRUFUHDWLQJJUHDWHU can thrive, and hopes to use the Civic Health Index to spark and FLYLFKHDOWKDQGYLWDOLW\WKURXJKRXWWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV VXVWDLQDFRQYHUVDWLRQDERXW*HRUJLD·VFLYLFHQJDJHPHQW CARL VINSON INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENT AT THE GEORGIAFORWARD UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA *HRUJLD)RUZDUGLVDQLQGHSHQGHQWQRQSDUWLVDQ F QRQSURÀW For more than 80 years, the Carl Vinson Institute of Government RUJDQL]DWLRQZRUNLQJWRLPSURYHWKHVWDWHRI*HRUJLDE\HQJDJLQJ -

Bi@Leaf in the Cumberlands by James W

Bi@leaf in the Cumberlands by James W. Kelly Without a doubt, the bigleaf and dusk was rapidly approaching, and magnolia, Magnolia macrophylla, is we did not remain long. I collected one of the most spectacular of the trees fruiting herbarium specimens from of the temperate world. It has the both species of the felled magnolias. largest undivided leaves of any Even at that time, the fruits were quite temperate woody plant. Its gorgeous large. On M. macrophylla, they would white flowers are often ten inches ultimately grow to the size of baseballs. across, with magenta crescents at the Two days later I returned to the bases of the three inner tepals. The same area shortly after ten o' clock in splendid leaves, particularly on open the morning before the weather grown trees, are often slightly became uncomfonably hot. This time I decurved, exposing their glaucous parked farther up the ridge near the reverses. side of a small ravine. I could not have picked a more beautiful day. The forest I have seen the bigleaf magnolia was still damp from an early morning cultivated in several locations, mostly shower. As in thc case of Magnolia arboretums, but I have always wanted fraseri in the Smoky Mountains, the to see it in its habitat. Like the saguaro opening made by the road benefited cactus in Arizona, such a distinct the bigleal' and umbrella magnolias. species would dominate the landscape. More light reached the forest floor to Since I would be near its habitat, I about one hundred feet from the edge wanted to make every effort to see a where the population was the densest. -

Flower Power

FLOWER POWER IDAHO BOTANICAL GARDEN WHAT IS A FLOWER? INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVE: When students finish this project, they will have gained respect for the beauty of flowers and appreciate their ecological and practical importance. INTRODUCTION Dear Teacher, The Idaho Botanical Garden is an outdoor learning environment. We want to make your visit comfortable and enjoyable, and ask that your students are dressed appropriately for the weather and have water, especially in the warm weather months. TERMS Angiosperms: Flowering plants that produce seeds enclosed in a fruit. Anthers: The boxlike structures at the top of stamens, where pollen is produced. Botanical garden: A place where plants are collected and displayed for scientific, educational and artistic purposes. Fertilization: The union of male sperm cells and female egg cells. Filament: The stalk of the stamen. Flower: The reproductive structure of an angiosperm. Fruit: A ripened ovary conaining seeds. Nectar: The sweet liquid produced by flowers to attract pollinators. Ovary: The hollow compartment at the base of the pistil which contains ovules. It develops into a fruit containing seeds. Ovules: The structures in a flower ovary that can develop into seeds. Pistil: The female part of a flower; stigma, style, and ovary. Pollen: A yellow, powder-like material containing sperm cells. Pollen tubes: Tubes that carry sperm cells from the stigma into the ovary. Pollination: The process of pollen coming together with the stigma of a flower. Pollinators: Animals which carry pollen from one flower to another. Seed: A structure containing a baby plant and its food supply, which is surrounded by a protective seed coat. -

SOS for Kids BW -2017.Pub

DITAT DEUS KATIE HOBBS Secretary of State State of Jlrizona SOS for Kids An Arizona Secretary of State publication My name is Arizona and my birthday is February 14. Did you know I wasn’t always a state? At one time I was a territory. Being a territory is a lot like being a kid. As a territory I could ask the United States government for things, but I didn’t always get them. I finally became the 48th state in 1912, and I’ve grown a lot since then. THE ARIZONA STATE QUARTER Do you have a quarter in your pocket? You might have the Arizona state quarter. Arizona’s quarter was released in 2008. The quarter design has the Grand Canyon and a rising sun at the top of the coin. To the right is a large Saguaro cactus with other desert cacti. A banner with the words “Grand Canyon State” separates the two Arizona scenes. This Activity Book may be reproduced for educational purposes. An electronic version is available for electronic download at www.azlibrary.gov. © 2017 Arizona Secretary of State’s Office. Design and graphics by Scott Cancelosi. 2 Katiee Hobbs, Secret ary of State An Arizona Secretary of State publication SOS for Kids WHERE AM I? Do you know where Arizona is? Circle the state on the map of the United States of America below. WHAT CITY OR TOWN DO YOU LIVE IN? Do you know what city or town you live in? Ask a parent, teacher or someone you know to help you. Write it below. -

Native Plants for Conservation, Restoration & Landscaping

ABOUT THE NATIVE PLANTS FOR CONSERVATION, WHAT ARE NATIVES? For more information, refer to field guides and publications RESTORATION AND LANDSCAPING PROJECT Native species evolved within specific regions and dispersed on local natural history for color, shape, height, bloom times This project is a collaboration between the Virginia Depart- throughout their range without known human involvement. and specific wildlife value of the plants that grow in your ment of Conservation and Recreation and the Virginia Native They form the primary component of the living landscape region. Visit a nearby park, natural area preserve, forest or Plant Society. VNPS chapters across the state helped to fund and provide food and shelter for wildlife management area to learn about common plant the 2011 update to this brochure. native animal species. Native associations, spatial groupings and habitat conditions. For The following partners have provided valuable assistance plants co-evolved with specific recommendations and advice about project design, throughout the life of this project: native animals over many consult a landscape or garden design specialist with thousands to millions of experience in native plants. TheNatureConservancy–VirginiaChapter•Virginia years and have formed TechDepartmentofHorticulture•VirginiaDepartmentof complex and interdependent WHAT ARE NON-NATIVE PLANTS? AgricultureandConsumerServices•VirginiaDepartment relationships. Our native Sometimes referred to as “exotic,” “alien,” or “non- of Environmental Quality, Coastal Zone Management fauna depend on native indigenous,” non-native plants are species introduced, Program•VirginiaDepartmentofForestry•Virginia flora to provide food and DepartmentofGameandInlandFisheries•Virginia Native intentionally or accidentally, into a new region by cover. -

Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus). Photo by Moez Ali. Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 Authors Moez Ali Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Kristen Beaupré National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd, Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 Patricia Valentine-Darby University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway Pensacola, Florida 32514 Chris White Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Project Contact Robert E. Bennetts National Park Service Southern Plains Network Capulin Volcano National Monument PO Box 40 Des Moines, New Mexico 88418 May 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colora- do, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource manage- ment, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

POLLINATION REQUIREMENTS for EDIBLE TREES Edible Tree Pollination Codes and Notes

POLLINATION REQUIREMENTS FOR EDIBLE TREES Edible Tree Pollination Codes and notes. S = Self Pollination; C =Cross pollinated; I = Insect Pollinated; W = Wind Pollinated; M/F = Male & Female Trees Almond C, I Cross-pollination by bees and other insects Apple C, I Cross-pollination with another apple varieties, and insect pollinated.. Apricot C/S, I Insect pollinated. Many varieties are self-pollinated, but planting two varieties can increase yields Bay laurel C, I, Trees are dioecious with separate male and female trees. Both must be grown if M/F seed is required. However, the leaves of the tree are most often used and can be harvested from any tree. Bees are the primary pollinators. Carob C, I/W, Typically dioecious, with separate male and female trees. Both wind and insect M/F pollinated. Male or hermaphrodite trees can be interplanted or male limbs can be grafted onto female trees for pollination. Cherry C/S, I All are insect pollinated. Sweet cherries and wild cherries require cross- pollination. Plant two or three varieties to ensure proper pollination. Sour cherries are self-pollinated. Citrus: All C/S, I Flowers are self-pollinating and also may be cross-pollinated. Honey bees Types effective at pollinating flowers. Desert fan C/S, I Primarily cross-pollinated by insects, but self-pollination can occur. palm Date palm C, I/W, Dioecious with separate male and female palms. Primarily wind pollinated, but M-F can also be insect pollinated. Typically pollinated by hand to improve yield. Elderberry C/S, I Self-pollinating, but produce more when cross-pollinated. -

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas William L. Halvorson and Brooke S. Gebow, editors Technical Report No. 68 United States Geological Survey Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona USGS Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona, Tucson The Sonoran Desert Field Station (SDFS) at The University of Arizona is a unit of the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (WERC). It was originally established as a National Park Service Cooperative Park Studies Unit (CPSU) in 1973 with a research staff and ties to The University of Arizona. Transferred to the USGS Biological Resources Division in 1996, the SDFS continues the CPSU mission of providing scientific data (1) to assist U.S. Department of Interior land management agencies within Arizona and (2) to foster cooperation among all parties overseeing sensitive natural and cultural resources in the region. It also is charged with making its data resources and researchers available to the interested public. Seventeen such field stations in California, Arizona, and Nevada carry out WERC’s work. The SDFS provides a multi-disciplinary approach to studies in natural and cultural sciences. Principal cooperators include the School of Renewable Natural Resources and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at The University of Arizona. Unit scientists also hold faculty or research associate appointments at the university. The Technical Report series distributes information relevant to high priority regional resource management needs. The series presents detailed accounts of study design, methods, results, and applications possibly not accommodated in the formal scientific literature. Technical Reports follow SDFS guidelines and are subject to peer review and editing. -

Saguaro Parts

SAGUARO PARTS 3) Point out the different parts you drew, Students identify the DOING THE A CTIVITY asking the students to name each one. basic structures of a Encourage the students to explain the saguaro and their SETTING THE STAGE functions of each part, filling in details from functions and label 1) Draw an outline of a simple saguaro the Saguaro Parts and Their Functions them on a picture of a cactus on the board including chart below. Write the name next to each saguaro. · an arm with flowers and fruits on it part as the group discusses it. · a pleated stem · spines · roots spanning shallowly below the ARIZONA SCIENCE surface of the ground STANDARDS 2) Ask the students, “What kind of a plant SC03-S4C1-01 is this?” (a saguaro cactus!) Explain that saguaros are special plants for a lot of reasons, and one is that they are only found right here, in the Sonoran Desert. OBJECTIVES Tell them that they are going to take a Students should: class about saguaros at the Desert · Identify the basic Museum that will make them saguaro structures of the experts. But to be experts, first they saguaro and describe need to learn about the saguaro’s parts. their functions. SAGUARO PARTS AND THEIR FUNCTIONS STEM · What are they for? (They allow the cactus to · What do you call the “trunk” of a saguaro? (stem) swell and take in water, or shrink as the water is · What is the stem for? (it stores water, makes food used.) for the plant, provides support) ROOTS SPINES · What part of the cactus is below the ground? · What are these spiky things called? (spines, not (roots) thorns) · What do they do for the cactus? (Take in rain · What are they for? (to help protect the cactus from water and dissolved minerals; anchor the cactus in feeding animals; to provide insulation for the growing the ground.) tips of the cactus’ arms and stem to protect them from heat and cold) FLOWERS · What do the flowers do? (Produce pollen and ARMS nectar to attract pollinators like bats, birds, and · What are these parts called? (arms) insects that visit them. -

Flora of the Whipple Mountains

$5.00 (Free to Members) VOL. 35, NO. 1 • WINTER 2007 FREMONTIA JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY FLORA OF THE WHIPPLE MOUNTAINS— THE “NOSE” OF CALIFORNIA INVASIVEINVASIVE PLANTSPLANTS IMPACTIMPACT TRADITIONALTRADITIONAL BASKETRY PLANTS NATIVE GRASSES IN THE GARDEN REMEMBERING GRADY WEBSTER BUCKEYEVOLUME 35:1, AS WINTERBONSAI 2007 AN ORCHID IN SAN DIEGO CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY FREMONTIA CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5113 Phone: (916) 447-CNPS (2677) Fax: (916) 447-2727 VOL. 35, NO. 1, WINTER 2007 Web site: www.cnps.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2007 MEMBERSHIP California Native Plant Society Membership form located on inside back cover; dues include subscriptions to Fremontia and the Bulletin Bart O’Brien, Editor Bob Hass, Copy Editor Mariposa Lily . $1,500 Family or Group . $75 Benefactor . $600 International . $75 Beth Hansen-Winter, Designer Patron . $300 Individual or Library . $45 Brad Jenkins, Jake Sigg, and Carol Plant Lover . $100 Student/Retired/Limited Income . $25 Witham, Proofreaders STAFF CHAPTER COUNCIL CALIFORNIA NATIVE Sacramento Office: Alta Peak (Tulare) . Joan Stewart PLANT SOCIETY Executive Director . Amanda Jorgenson Bristlecone (Inyo-Mono) . Sherryl Taylor Development Director/Finance Channel Islands . Lynne Kada Dedicated to the Preservation of Manager . Cari Porter the California Native Flora Dorothy King Young (Mendocino/ Membership Assistant . Christina Sonoma Coast) . Lori Hubbart The California Native Plant Society Neifer East Bay . Elaine P. Jackson (CNPS) is a statewide nonprofit organi- El Dorado . Amy Hoffman zation dedicated to increasing the un- At Large: Kern County . Lucy Clark derstanding and appreciation of Califor- Fremontia Editor . Bart O’Brien Los Angeles/Santa Monica Mtns . -

Tree Elevations.Pdf

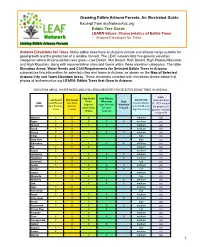

! Growing Edible Arizona Forests, An Illustrated Guide Excerpt from leafnetworkaz.org Edible Tree Guide LEARN Values, Characteristics of Edible Trees Network • Arizona Elevations for Trees Linking Edible Arizona Forests Arizona Elevations for Trees. Many edible trees have an Arizona climate and altitude range suitable for good growth and the production of a reliable harvest. The LEAF network lists five general elevation categories where Arizona edible trees grow—Low Desert, Mid Desert, High Desert, High Plateau/Mountain and High Mountain, along with representative cities and towns within these elevation categories. The table Elevation Areas, Water Needs and Chill Requirements for Selected Edible Trees in Arizona summarizes this information for selected cities and towns in Arizona, as shown on the Map of Selected Arizona City and Town Elevation Areas. These elevations correlate with elevations shown below fruit photos at leafnetworkaz.org LEARN: Edible Trees that Grow in Arizona. T!TB6;UVW%6XT6A.%C6;TX%WTTYA%6WY%*&U!!%XTZ[UXT\TW;A%FVX%AT!T*;TY%TYU]!T%;XTTA%UW%6XU^VW6% 4256$,-.-/0% 4256$&780-89:$ '4())?$ )*+$,-.-/0$$ 123$,-.-/0$$ <=!#"$>%#?$$ &1)9(%>$,E$$2% 8=1>$.% 1*9;082;%% 4256$$ !"##$$ !"#$%&"'"()% 671.%*"("% =1E%HIJIK+2L-9% ?+2@5"2.% /"@$.%/9$(<1D.%% 1*9;082;$ NI%J%MOPF%2$$:$:% %&#'(#%$ *+,-.%/01$2+3.% 89"2:$.% 5$:%IKJMK%+2L-9% A+$99"%B+(,".% C+2(=1E.%% F="@(,"G% Q19%R91R$9%>):% 4)5"% ;)<(12% 0+@0%NKJOK%+2L-9% C+==<13% ;)>"%*+,-% @91E,0.%Q9)+,%($,% "2:%@91E,0% $=7@*;3$ S% S% S% 5$:+)5% -$(% $=AA7-$ S% S% S% S% S% 5$:+)5% -$(% $=A/2B*0$ -

Postfire Regeneration in Arizona's Giant Saguaro Shrub Community

Postfire Regeneration in Arizona's Giant Saguaro Shrub Community R.C. Wilson, M.G. Narog2, A.L. Koonce2, and B.M. Corcoran2 Abstract.---In May 1993, an arsonist set numerous fires in the saguaro shrub vegetation type on the Mesa Ranger District, Tonto National Forest. In January 1994, we began a postfire examination in these burned areas to determine the potential of the shrub species for resprouting after fire. Fire girdled saguaros and charred shrub skeletons covered the burned areas. Shrub skeletons were examined for basal sprouts or branch regrowth, Resprouting from branches of shrubs was evident within islands of partially burned areas and along the edges of the burns. Basal sprouting was observed on plants that had no apparent viable upper branches. This implies that some shrub species in the saguaro shrub association studied have the potential to regenerate after a spring wildfire. INTRODUCTION A review of current fire records, 1973 to 1992, from the flammable exotic grasses that connect many of these patches Tonto National Forest, Arizona, reveals a continuing increase and purportedly increase ignitions and acreage burned. in fire frequency and acreage burned in upland Sonoran desert The role of fire and grazing in Arizona desert communities. The number of fires in desert habitats grassland-shrub communities has been debated and evaluated approaches those in timber, but exceeds all other habitats in for over 70 years. Leopold (1924) called for a serious actual acres burned (Narog et. al. in press). Earlier studies of consideration of his perceived problem of shrub encroachment fire occurrence reported similar increases in desert-shrub and into grasslands.