Turkmenistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

49370-002: National Power Grid Strengthening Project

Initial Environmental Examination Final Report Project No.: 49370-002 October 2020 Turkmenistan: National Power Grid Strengthening Project Volume 4 Prepared by the Ministry of Energy, Government of Turkmenistan for the Asian Development Bank. The Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 49370-002: TKM TKM Power Sector Development Project 81. Out of these IBAs, eight IBAs are located close to phase I Transmission line alignments. Four IBAs are located close to proposed Gurtly (Ashgabat) to Balkanabat Transmission line. And four falls close to existing Sardar (West) to Dashoguz Transmission line. No IBA falls close to Dashoguz-Balkan Transmission line. The view of these IBAs with respect to transmission alignment of phase I are shown at Figure 4.17. 82. There are 8 IBAs along phase II alignment. Two IBAs, i.e. Lotfatabad & Darregaz and IBA Mergen is located at approx 6.0 km &approx 9.10 km from alignment respectively. The view of these IBAs with respect to transmission alignment of phase II is shown at Figure 4.18. : Presence of Important Bird Areas close to Proposed/existing -

DRUG SITUATION and DRUG POLICY P-PG (2015) 13 by Alex CHINGIN and Olga FEDOROVA December 2014

Turkmenistan DRUG SITUATION AND DRUG POLICY P-PG (2015) 13 By Alex CHINGIN and Olga FEDOROVA December 2014 Pompidou Group of the Council of Europe Co-operation Group to Combat Drug Abuse and Illicit trafficking in Drugs 3 Preface The Pompidou Group is publishing a series of “Country Profiles” to describe the current drug situation and policy of its Member States and States and countries of the European neighbourhood, including Central Asia. The aim is to provide an overview on the issues and developments related to illicit drugs and provide information about the policies, laws and practical responses in place. It is hoped that the Country Profiles will become a useful source of information and reference for policy makers, practitioners and other interested audiences. This publication examines the state of affairs and drugs policy in Turkmenistan and provides a descriptive analysis for an interested audience on drug related developments in the country, existing policies and legislation, as well as information on prevention and treatment measures and law enforcement activities. Furthermore, the role of substitution treatment and harm reduction programmes as well as treatment options available in prisons are described. In addition, it provides an overview of the various international commitments and relations with neighbouring countries in the areas of demand and supply reduction. Overall, the publication provides an overview on the state of implementation of the national drug policy in Turkmenistan. The Pompidou Group expresses its gratitude and appreciation to the Department for Antidrug Policies of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers of Italy for their financial support to the publication of the Pompidou Group Country Profile series. -

Turkmenistan – Making the Most of Desert Resources

Turkmenistan Making the Most of Desert Resources urkmen hospitality is legendary, its roots There is little forested land. In fact, four-fifths of the in the distant past. Beyond the traditional country’s surface is desert—most of it the Karakum Khosh geldiniz (welcome), a host’s sacred (Garagum in Turkmen, the official language). And duty has always been to be hospitable to most of the remaining 20% of land is occupied Tguests, even if they are strangers. The hardship of by steep mountains. At the southwest edge of the life and travel in the desert that makes up most of Karakum, the Kopet-Dag Range rises up along the country is such that finding a friendly refuge Turkmenistan’s southern border. This range forms could be a matter of life or death. Inhospitality to a part of the Trans-Eurasian seismic belt, which is traveler is virtually unthinkable. unstable and has caused violent earthquakes in the country. An Uncompromising Terrain Turkmenistan’s most important river is the Amu Darya, the longest river in Central Asia, which Turkmenistan, the second largest Central Asian emanates from the Pamir mountains and flows country, covers 488,100 square kilometers, northwesterly through Turkmenistan. Much of its measuring about 1,100 kilometers from east to water is diverted to the west for irrigation via the west and 650 kilometers from north to south, Karakum Canal. Other major rivers are the Tejen, Upper: The Yangkala Canyon in northwestern Turkmenistan. Lower: The between the Caspian Sea in the west and the the Murgab, and the Atrek. Mausoleum of Turkmenbashi in Ahal Amu Darya River in the east. -

The Report of Data Collection Survey on the Partnership Between the Private Sector in Hokkaido and Mongolia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus Area

THE REPORT OF DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN THE PRIVATE SECTOR IN HOKKAIDO AND MONGOLIA, CENTRAL ASIA, AND THE CAUCASUS AREA Final Report March 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Hokkaido Intellect Tank International Development Center of Japan 3R JR 16-002 CONTENTS Ⅰ Summary ............................................................................................................................................ - 1 - 1 Background of the Survey .................................................................................................................... - 1 - 2 Purpose of the Survey .......................................................................................................................... - 1 - 3 Survey Implementation Policy ............................................................................................................. - 2 - (1) Collaboration with the Policies of Japan and Multilateral/Bilateral Efforts ...................................... - 2 - (2) Country Analyses Based on the International Situation .................................................................... - 2 - (3) Discussion Based on the Japanese Policy for Support to Target Countries ...................................... - 2 - (4) Technologies and Knowledge from Hokkaido Applicable to Target Countries ................................ - 2 - (5) Examination of the Promotion of Private Collaboration Considering Past Lessons ......................... - 3 - 4 Flow of Survey Implementation .......................................................................................................... -

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan FINDINGS : Severe religious freedom violations and official harassment of religious adherents persist in Turkmenistan. Despite a few limited reforms undertaken by President Berdimuhamedov since 2007, the country’s laws, policies, and practices continue to violate international human rights norms, including those on freedom of religion or belief. Police raids and other harassment of registered and unregistered religious groups continue. The highly repressive 2003 religion law remains in force, causing major difficulties for religious groups to function legally, and has justified police raids and arrests. Turkmen law does not allow a civilian alternative to military service, and six Jehovah’s Witnesses are imprisoned for conscientious objection. In light of these severe violations, USCIRF continues to recommend in 2012 that the U.S. government designate Turkmenistan as a “country of particular concern,” or CPC. The Commission has recommended CPC designation for Turkmenistan since 2000, but the State Department has never followed this recommendation. Under the late President Niyazov, Turkmenistan was among the world’s most repressive and isolated states. Niyazov’s personality cult dominated public life, and there is evidence that President Berdimuhamedov is building a cult to justify his own dominance, but without religious overtones. While President Berdimuhamedov has ordered a few limited reforms and released the former chief mufti from prison in 2007, since then his government has not adopted essential systemic legal reforms on freedom of religion or belief and other human rights. Moreover, the Turkmen government has reinstituted restrictive policies regarding education, foreign travel, dual citizenship, and telecommunications that have again led to the country’s extreme isolation. -

Essential Turkmenistan 2020 Essential Turkmenistan from the Capital to the Caspian

Essential Turkmenistan 2020 Essential Turkmenistan From the Capital to the Caspian Flexible Essential Trip – Classic Private Journey – 12 Days Your choice of dates, suggested start day: Friday From the marble and gold monuments of the capital, Ashgabat, and the UNESCO-listed ruins of Parthian Nisa, head into the mountains to visit a silk-weaver in a tribal village home. Discover the country’s only seaport, Turkmenbashi, where the abundant oil is refined and shipped over the shallow Caspian Sea, then drive through glorious, striated Yangykala Canyon. Explore UNESCO-listed Merv’s five ancient cities and spend some time admiring the Zoroastrian sites of Bronze Age Gonur Depe. Camp at the “Door to Hell,” the burning Darvaza Gas Crater, and survey Turkmenistan’s third UNESCO Site, Kunya-Urgench, ancient capital of Khorezm. © 1996-2020 MIR Corporation 85 South Washington St, Ste. 210, Seattle, WA 98104 • 206-624-7289 • 206-624-7360 FAX • Email [email protected] 2 Daily Itinerary Day 1, Friday Arrive Ashgabat, Turkmenistan Day 2, Saturday Ashgabat Day 3, Sunday Ashgabat • Nohur • Serdar Day 4, Monday Serdar • Karakala • Turkmenbashi Day 5, Tuesday Turkmenbashi • Gozli Ata Day 6, Wednesday Gozli Ata • fly to Ashgabat Day 7, Thursday Ashgabat • Mary Day 8, Friday Mary • Merv Day 9, Saturday Mary • fly to Ashgabat • Darvaza Day 10, Sunday Darvaza • Dashoguz • Kunya-Urgench • fly to Ashgabat Day 11, Monday Ashgabat Day 12, Tuesday Depart Ashgabat © 1996-2020 MIR Corporation 85 South Washington St, Ste. 210, Seattle, WA 98104 • 206-624-7289 • 206-624-7360 -

Diversity of the Mountain Flora of Central Asia with Emphasis on Alkaloid-Producing Plants

diversity Review Diversity of the Mountain Flora of Central Asia with Emphasis on Alkaloid-Producing Plants Karimjan Tayjanov 1, Nilufar Z. Mamadalieva 1,* and Michael Wink 2 1 Institute of the Chemistry of Plant Substances, Academy of Sciences, Mirzo Ulugbek str. 77, 100170 Tashkent, Uzbekistan; [email protected] 2 Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 364, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +9-987-126-25913 Academic Editor: Ipek Kurtboke Received: 22 November 2016; Accepted: 13 February 2017; Published: 17 February 2017 Abstract: The mountains of Central Asia with 70 large and small mountain ranges represent species-rich plant biodiversity hotspots. Major mountains include Saur, Tarbagatai, Dzungarian Alatau, Tien Shan, Pamir-Alai and Kopet Dag. Because a range of altitudinal belts exists, the region is characterized by high biological diversity at ecosystem, species and population levels. In addition, the contact between Asian and Mediterranean flora in Central Asia has created unique plant communities. More than 8100 plant species have been recorded for the territory of Central Asia; about 5000–6000 of them grow in the mountains. The aim of this review is to summarize all the available data from 1930 to date on alkaloid-containing plants of the Central Asian mountains. In Saur 301 of a total of 661 species, in Tarbagatai 487 out of 1195, in Dzungarian Alatau 699 out of 1080, in Tien Shan 1177 out of 3251, in Pamir-Alai 1165 out of 3422 and in Kopet Dag 438 out of 1942 species produce alkaloids. The review also tabulates the individual alkaloids which were detected in the plants from the Central Asian mountains. -

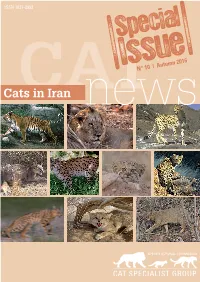

Tiger in Iran

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Mammals of the Caucasus

planifrons Falc. and Equus stenonis Cocchi have been identified. The breccia is underlain by a layer of doleritic lava and is covered by lacustrine sands and clays. The lake sediments are overlain by a layer of dolorite (Zaridze and Tatrishvili, 1948). Thus, in that area, the mammals lived and died during a period when the volcanos in the Lesser Caucasus were dornnant. The next transgression in the Caspian ->- N Basin, a somewhat smaller one, is known ^.AA.>.>J>-Jn,*^f^^v-»L*.-.->4-W-vn-Wtv^ as the Apsheron sea. ;'<,•.•''' OS The Kura bay of the Apsheron sea OB reached the longitude of Kirovabad. The :o:.\-:e:.--i Terek bay was temporarily connected with the Euxinic basin by a strait in the Manych area. The sea reached the latitude of Sarepta and [Lake] Inder in the north. •'•p.;-. .- •«.•.. e". ;..•.*• o*. •.•.; ''•',' 45 o'. • o". ' '•'o'.'- o." ; •.b..'i^-'.'-o'".^•.•<>.• The climate and landforms of the 4>- b-fi.: Caucasus in Apsheron time probably remained the same as in the Akchagyl, and the volcanic activity was of about the same c?o intensity. Torrential mudflows, caused by heavy rains, carried volumes of gravel and boulders from the mountains (Kudryavtsev, 1933); these boulders can 68 'S::^^^^ now be seen on the Kakhetia Plain. d - 5 The land vegetation known from the Apsheron deposits in the Shiraki Steppe consisted of spruce (Picea orientalis) and a number of Recent forms: beech, oak, aspen, apple, willow, filbert, Turkish filbert, walnut (Juglans regia), zelkova, honeysuckle; and Hyrcanian forms: f < oak (Quercus castanei folia), alder (Alnus subcordata), maple (Acer ibericum) (Palibin, 1936). -

Turkmenistan

BTI 2020 Country Report Turkmenistan This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2020. It covers the period from February 1, 2017 to January 31, 2019. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of governance in 137 countries. More on the BTI at https://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2020 Country Report — Turkmenistan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2020 | Turkmenistan 3 Key Indicators Population M 5.9 HDI 0.710 GDP p.c., PPP $ 19270 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.6 HDI rank of 189 108 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 68.0 UN Education Index 0.628 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 51.6 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 5.0 Sources (as of December 2019): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2019 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2019. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary In 2017 and 2018, Turkmenistan made further adjustments to its legislation in line with international legal norms. -

The Geopolitics of Natural Gas Turkmenistan: Real Energy Giant Or Eternal Potential?

The Geopolitics of Natural Gas Turkmenistan: Real Energy Giant or Eternal Potential? Harvard University’s Belfer Center and Rice University’s Baker Institute Center for Energy Studies December 2013 JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY TURKMENISTAN: REAL ENERGY GIANT OR ETERNAL POTENTIAL? BY MARTHA BRILL OLCOTT, PH.D. SENIOR ASSOCIATE RUSSIA AND EURASIA PROGRAM CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE DECEMBER 10, 2013 Turkmenistan: Real Energy Giant or Eternal Potential? THESE PAPERS WERE WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER (OR RESEARCHERS) WHO PARTICIPATED IN A BAKER INSTITUTE RESEARCH PROJECT. WHEREVER FEASIBLE, THESE PAPERS ARE REVIEWED BY OUTSIDE EXPERTS BEFORE THEY ARE RELEASED. HOWEVER, THE RESEARCH AND VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THESE PAPERS ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL RESEARCHER(S), AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. © 2013 BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY THIS MATERIAL MAY BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION, PROVIDED APPROPRIATE CREDIT IS GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. 2 Turkmenistan: Real Energy Giant or Eternal Potential? Acknowledgments The Center for Energy Studies of Rice University’s Baker Institute would like to thank ConocoPhillips and the sponsors of the Baker Institute Center for Energy Studies for their generous support of this program. The Center for Energy Studies further acknowledges the contributions by study researchers and writers. Energy Forum Members Advisory Board Associate Members Accenture Direct Energy The Honorable & Mrs. Hushang Ansary Hess Corporation Baker Botts L.L.P. Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. -

Turkmenistan Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Turkmenistan This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Turkmenistan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Turkmenistan 3 Key Indicators Population M 5.7 HDI 0.691 GDP p.c., PPP $ 16880 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.7 HDI rank of 188 111 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 67.6 UN Education Index 0.634 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 50.4 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 4.2 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary During the period under review, the government undertook reforms to harmonize legislation with international standards while intensifying cooperation with foreign countries and international organizations.