CH-375 Chapel Point State Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

Anacostia River Watershed Restoration Plan

Restoration Plan for the Anacostia River Watershed in Prince George’s County December 30, 2015 RUSHERN L. BAKER, III COUNTPreparedY EXECUTIV for:E Prince George’s County, Maryland Department of the Environment Stormwater Management Division Prepared by: 10306 Eaton Place, Suite 340 Fairfax, VA 22030 COVER PHOTO CREDITS: 1. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 7. USEPA 2. Tetra Tech, Inc. 8. USEPA 3. Prince George’s County 9. Montgomery Co DEP 4. VA Tech, Center for TMDL and 10. PGC DoE Watershed Studies 11. USEPA 5. Charles County, MD Dept of 12. PGC DoE Planning and Growth Management 13. USEPA 6. Portland Bureau of Environmental Services _Tom Liptan Anacostia River Watershed Restoration Plan Contents Acronym List ............................................................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of Report and Restoration Planning ............................................................................... 3 1.1.1 What is a TMDL? ................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.2 What is a Restoration Plan? ............................................................................................... 4 1.2 Impaired Water Bodies and TMDLs .............................................................................................. 6 1.2.1 Water Quality Standards .................................................................................................... -

Maryland's 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards

Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards EPA Approval Date: July 11, 2018 Table of Contents Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards ............................................ 3 Nationally Recommended Water Quality Criteria Considered with Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Re-evaluation of Maryland’s Restoration Variances ...................................................................... 5 Other Future Water Quality Standards Work ................................................................................. 6 Water Quality Standards Amendments ........................................................................................... 8 Designated Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 Criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Antidegradation.......................................................................................................................... 24 2 Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards The Clean Water Act (CWA) requires that States review their water quality standards every three years (Triennial Review) and revise the standards as necessary. A water quality standard consists of three separate but related -

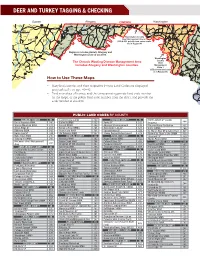

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Garrett Allegany CWDMA Washington Frederick Carroll Baltimore Harford Lineboro Maryland Line Cardiff Finzel 47 Ellerlise Pen Mar Norrisville 24 Whiteford ysers 669 40 Ringgold Harney Freeland 165 Asher Youghiogheny 40 Ke 40 ALT Piney Groev ALT 68 615 81 11 Emmitsburg 86 ge Grantsville Barrellville 220 Creek Fairview 494 Cearfoss 136 136 Glade River aLke Rid 546 Mt. avSage Flintstone 40 Cascade Sabillasville 624 Prospect 68 ALT 36 itts 231 40 Hancock 57 418 Melrose 439 Harkins Corriganville v Harvey 144 194 Eklo Pylesville 623 E Aleias Bentley Selbysport 40 36 tone Maugansville 550 419410 Silver Run 45 68 Pratt 68 Mills 60 Leitersburg Deep Run Middletown Springs 23 42 68 64 270 496 Millers Shane 646 Zilhman 40 251 Fountain Head Lantz Drybranch 543 230 ALT Exline P 58 62 Prettyboy Friendsville 638 40 o 70 St. aulsP Union Mills Bachman Street t Clear 63 491 Manchester Dublin 40 o Church mithsburg Taneytown Mills Resevoir 1 Aviltn o Eckhart Mines Cumberland Rush m Spring W ilson S Motters 310 165 210 LaVale a Indian 15 97 Rayville 83 440 Frostburg Glarysville 233 c HagerstownChewsville 30 er Springs Cavetown n R 40 70 Huyett Parkton Shawsville Federal r Cre Ady Darlingto iv 219 New Little 250 iv Cedar 76 140 Dee ek R Ridgeley Twiggtown e 68 64 311 Hill Germany 40 Orleans r Pinesburg Keysville Mt. leasP ant Rocks 161 68 Lawn 77 Greenmont 25 Blackhorse 55 White Hall Elder Accident Midlothian Potomac 51 Pumkin Big pringS Thurmont 194 23 Center 56 11 27 Weisburg Jarrettsville 136 495 936 Vale Park Washington -

Julrec99.Pdf

July 1999 ForFor thethe RecordRecord Oil operation permit for sludge solidification permit TAMKO ROOFING PRODUCTS, INC. - 4500 The following is a list of PHIPPS CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTORS, OTTIS E. BREEDING , SR. – Denton, MD Tamko Drive, Frederick, MD 21701. (TR MDE’s permiting activity from - 4300 Shannon Drive, Baltimore, MD 21213. (89-SP-0332) Application received for a 5447) Received an air permit to construct for a May 15 - June 15, 1999 (TR 5452) Received an air permit to construct renewal of a surface mine permit on Route 313 modification to an existing storage tank area for one concrete crusher For information on these PROFESSIONAL DISPOSAL SERVICES, INC. Carroll County Garrett County permits, please call MDE’s - 7107 Commercial Avenue, Baltimore, MD 21237. (99-OPX-2597) Oil operation permit Environmental Permits Service RONALD YOHN FARM - Wentz Road, HARBISON-WALKER REFRACTORIES - for sludge solidification Manchester, MD 21102. Sewage sludge 16306 Bittinger Road, Grantsville, MD 21536. Center at (410) 631-3772. STRATUS PETROLEUM CORPORATION - application on agricultural land (1999-11-00026) Air quality permit to operate 3100 Vera Street, Baltimore City, MD 21226. JENKINS DEVELOPMENT CO., - Applications Received (99-ODS-3487) Surface water discharge for oil Cecil County Lonaconing, MD (SM-87-411) Application terminal received for significant modification. U.S. TAG & LABEL COMPANY - 2208 HARBOUR VIEW WASTE WATER TREAT- Aisquith Street, Baltimore, MD 21218. (TR Allegany County MENT PLANT - Dartmouth Road, Chesa- 5426) Received an air permit to construct for Harford County peake City, MD 21915. (99DP0496) Surface one heat-set web printing press AMCELLE RF - Route 220, Cumberland, MD municipal discharge permit 21502. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Birding in Southern Maryland Calvert, Charles, St

Birding in Southern Maryland Calvert, Charles, St. Mary’s and Southern Prince George’s Counties Produced by Southern Maryland Audubon Society Society Birding in Southern Maryland This brochure was especially designed for birders. If you are traveling through and have the urge to bird for a while, we hope this brochure will help you locate some spots local birders enjoy without wasting time looking for them. Our list in the back of this brochure includes some less common sightings as well as resident and migrant birds. If you are a resident birder, we hope you will eventually be able to put a checkmark beside each species. Good Birding! NOTE: Any birds sighted which are not on the checklist in the back of this brochure or are marked with an asterisk should be reported to [email protected]. Species notations, such as preferred habitat and seasonality are listed at the end of the checklist in the back of this brochure. Olive Sorzano 1920-1989 This brochure is dedicated to the memory of Olive Sorzano, a charter member of the Southern Maryland Audubon Society from 1971 until her death in 1989. A warm, generous, kind and thoughtful person, Olive came to represent the very soul of Southern Maryland Audubon. Throughout the years, she held various positions on the Board of Directors and willingly helped with nearly all activities of the growing chapter. She attended every membership meeting and every field trip, always making sure that new members were made welcome and novice birders were encouraged and assisted. Living on the Potomac River in Fenwick, a wooded community in Bryans Road, Maryland, she studied her land and water birds, keeping a daily list of what she saw or heard with her phenomenal ears. -

Report of Investigations 71 (Pdf, 4.8

Department of Natural Resources Resource Assessment Service MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Emery T. Cleaves, Director REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO. 71 A STRATEGY FOR A STREAM-GAGING NETWORK IN MARYLAND by Emery T. Cleaves, State Geologist and Director, Maryland Geological Survey and Edward J. Doheny, Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey Prepared for the Maryland Water Monitoring Council in cooperation with the Stream-Gage Committee 2000 Parris N. Glendening Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend Lieutenant Governor Sarah Taylor-Rogers Secretary Stanley K. Arthur Deputy Secretary MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21401 General DNR Public Information Number: 1-877-620-8DNR http://www.dnr.state.md.us MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 2300 St. Paul Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218 (410) 554-5500 http://mgs.dnr.md.gov The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin, or physical or mental disability. COMMISSION OF THE MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. GORDON WOLMAN, CHAIRMAN F. PIERCE LINAWEAVER ROBERT W. RIDKY JAMES B. STRIBLING CONTENTS Page Executive summary.........................................................................................................................................................1 Why stream gages?.........................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction............................................................................................................................................................4 -

Religious Freedom Byway Management Plan

Religious Freedom Byway Management Plan The Beginnings of Religious Freedom in America October 2008 This page intentionally left blank Religious Freedom Byway Management Plan The Beginnings of Religious Freedom in America Prepared for: Charles and St. Mary’s Counties in Maryland and Maryland Offi ce of Tourism Development Maryland State Highway Administration Prepared By: Lardner/Klein Landscape Architects, P.C. John Milner Associates, Inc. National Trust for Historic Preservation, Heritage Tourism Program Daniel Consultants, Inc. with the assistance of Religious Freedom Byway Advisory Committee October 2008 Acknowledgements The Religious Freedom Byway Management Plan was developed with the assistance of an Advisory Committee comprised of representatives from each of the participating Counties, Southern Maryland Heritage Area, Maryland Offi ce of Tourism Development, Maryland State Highway Administration, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Department of Historic Resources, and Maryland Department of Planning. Thank you to the following Advisory Committee members, local offi cials, and public servants for their time and effort in helping to identify issues and review proposed strategies for the development of the plan. Christine Arnold-Lourie, Professor, College of Southern Maryland Vivian Mills, Conservancy for Charles County, Inc. Marsha Back, Nanjemoy Vision Group Jay Moose, Thomas Stone National Historic Site Reverend John Ball, Rector, Trinity Episcopal Church Reverend William Jessee Neat, Christ Episcopal Church Christine Bergmark , Director of Agricultural Programs, Tri-County Coun- Debra Pence, Museum Division Manager, St. Mary’s County Museum cil for Southern Maryland Division Ronald Brown, Charles County Heritage Commission Bruce Perrygo Mike Brown, Vice President, United Committee for African American Tony Puleo, Senior Planner, Charles County Department of Planning Contributions and Growth Management Rev. -

Port Tobacco River Watershed Assessment Summary

LOWER PATUXENT RIVER WATERSHED ASSESSMENT JUNE | 2016 PREPARED FOR Charles County Department of Planning and Growth Management Watershed Protection and Restoration Program 200 Baltimore St., La Plata, MD 20646 PREPARED BY KCI TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 936 RIDGEBROOK ROAD SPARKS, MD 21152 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Lower Patuxent Watershed Assessment was a collaborative effort between Coastal Resources, Inc., KCI Technologies, Inc. and Charles County Department of Planning and Growth Management. The resulting report was authored by the following individuals from KCI Technologies, Inc. and Charles County. Susanna Brellis | KCI Technologies, Inc. Megan Crunkleton | KCI Technologies, Inc. Colin Hill | KCI Technologies, Inc. Bill Frost | KCI Technologies, Inc. Michael Pieper | KCI Technologies, Inc. James Tomlinson | KCI Technologies, Inc. Charles Rice | Charles County P&GM Karen Wiggen | Charles County P&GM Lower Patuxent River Watershed Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 1.1 Background ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 1.2 Watershed description --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.3 Previous Watershed studies and Assessments -------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.4 Goals --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.4.1 Watershed