Issue 5 May 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NZSA Bulletin of New Zealand Studies

NZSA Bulletin of New Zealand Studies Issue Number 2 Edited by Ian Conrich ISSN 1758-8626 Published 2010 by Kakapo Books 15 Garrett Grove, Clifton Village, Nottingham NG11 8PU © 2010 Kakapo Books © 2010 for the poetry, which remains with the authors. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise, or stored in an information retrieval system without written permission from the publisher. Editor: Ian Conrich Assistant Editor: Tory Straker Typesetter: Opuscule Advisory Board: Dominic Alessio (Richmond The American International University) Clare Barker (University of Birmingham) Kezia Barker (Birkbeck, University of London) Claudia Bell (University of Auckland, New Zealand) Judy Bennett (University of Otago, New Zealand) Roger Collins ( Dunedin, New Zealand) Sean Cubitt (University of Melbourne, Australia) Peter Gathercole (Darwin College, University of Cambridge) Nelly Gillet (University of Technology of Angoulême, France) Manying Ip (University of Auckland, New Zealand) Michelle Keown (University of Edinburgh) Yvonne Kozlovsky-Golan (Sapir Academic College, Israel) Geoff Lealand (University of Waikato, New Zealand) Martin Lodge (University of Waikato, New Zealand) Bill Manhire (Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand) Rachael Morgan (Edinburgh) Michaela Moura-Koçuglu (Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany) David Newman (Simon Fraser University, Canada) Claudia Orange (Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand) Vincent O’Sullivan (Victoria University of Wellington, -

Office for Contemporary Art Norway / Valiz

and Criticism and Indigenous Art, Curation Sovereign Words. Sovereign Words García-Antón Katya by Edited Tripura. Bikash Sontosh Tripura, Prashanta Tamati-Quennell, Megan Garneau, Biung Ismahasan, Kimberley Moulton, Máret Ánne Sara, Venkat Raman Singh Shyam, Irene Snarby, ÁndeDaniel Somby, Browning, Kabita Chakma, Megan Cope, Santosh Kumar Das, Hannah Donnelly, Léuli Māzyār Luna’i Eshrāghi, David Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism Office for Contemporary Art Norway / Valiz With this publication we pay respect to our peers in Sápmi, as well as to the myriad Indigenous histories, presents and futures harboured in lands and oceans across the world. We acknowledge their Ancestors and the stories of survivance (survival, resistance and presence) in the face of colonial mechanisms that are still ongoing. We also honour the agency possible in the constitution of alliances between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities within the fields of culture and beyond. Sovereign Words. Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism Edited by Katya García-Antón Office for Contemporary Art Norway Valiz, Amsterdam – 2018 7 Preface Katya García-Antón Sounding the Global Sovereign Histories Indigenous. Language, of the Visual Contemporaneity and Indigenous Art Writing 15 Can I Get a Witness? 63 Jođi lea buoret go oru. Indigenous Art Criticism Better in Motion than at David Garneau Rest. Iver Jåks 33 What Does or Should (1932–2007) ‘Indigenous Art’ Mean? Irene Snarby Prashanta Tripura 77 Toi te kupu, toi te mana, 47 History and Context of toi te whenua. The Madhubani (Mithila) Art Permanence of Language, Santosh Kumar Das Prestige and Land Megan Tamati-Quennell 97 Sovereignty over Representation. Indigenous Cinema in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh Kabita Chakma Statues, Maps, Stories Sovereign World-Building. -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each. -

YOUNG SCIENTIST of the YEAR Internationalisation the ALUMNUS BEHIND FIREFOX CHAMPION SCULLER SPRING 2006 – Ingenio the University of Auckland Alumni Magazine

THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND ALUMNI MAGAZINE SpRING 2006 SHAPING AUCKLAND YOUNG SCIENTIST OF THE YEAR INTERNatIONALISatION THE ALUMNUS BEHIND FIREFOX CHAMPION SCULLER SPRING 2006 – INGENIO THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND ALUMNI MAGAZINE In this issue . Ingenio – The University of Auckland alumni magazine Spring 2006 ISSN 1176-211X Editor Tess Redgrave Photography Godfrey Boehnke Design/production Ingrid Atvars 5 9 10 32 Publication management and proof reading Bill Williams Advertising manager Don Wilson 4 Letters to the Editor OpINION Editorial contact details Entrepreneurship Ingenio 25 Communications and Marketing UNIVERSITY NEWS The University of Auckland Eminent Mäori professor dies ALUMNI Private Bag 92 019 4 Auckland 1142 New Zealand 5 London Royal Society, NZ Trio, 26 Top fox Ben Goodger Level 10 Fisher Building Primatologist 18 Waterloo Quadrant Auckland 28 News and noticeboard Telephone 64 9 373 7599 Leigh Marine, Long QT syndrome 6 Film-maker Roseanne Liang ext 84149 test, Maurice Wilkins Centre 30 Facsimile 64 9 373 7047 email [email protected] www.auckland.ac.nz/ingenio HISTORY PHILANTHROPY Engineering Chris Bennett How alumni keep in touch 7 32 To ensure that you continue to 8 Education 30 Jean Heywood receive Ingenio, and to subscribe to @auckland, the University’s email 9 Old Government House newsletter for alumni and friends, REGULAR COLUMNS please update your details at: RESEARCH www.alumni.auckland.ac.nz/update 34 Sport Alumni Relations Office 10 Young Scientist The University of Auckland 35 Alumni snapshots 19A Princes Street 12 Shaping Auckland Art Private Bag 92019 36 Auckland 1142 New Zealand Books StRatEGY 37 odfrey Boehnke Telephone 64 9 373 7599 G – ext 82246 18 Internationalisation 38 Student life email [email protected] AGE M www.alumni.auckland.ac.nz I TEACHING Copyright ER V Articles reflect personal opinions O Poetry in transmission C and are not those of The University 22 of Auckland. -

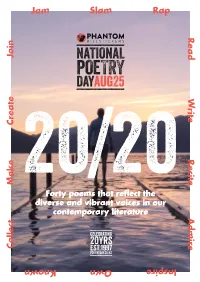

Jam Inspire Create Join Make Collect Slam Own Rap Known Read W Rite

Jam Slam Rap Read Join Write Create Recite Make 20/20 Forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant voices in our contemporary literature Admire Collect Inspire Known Own 20 ACCLAIMED KIWI POETS - 1 OF THEIR OWN POEMS + 1 WORK OF ANOTHER POET To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, we asked 20 acclaimed Kiwi poets to choose one of their own poems – a work that spoke to New Zealand now. They were also asked to select a poem by another poet they saw as essential reading in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection, a selection of forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant range of voices in New Zealand’s contemporary literature. Published in 2017 by The New Zealand Book Awards Trust www.nzbookawards.nz Copyright in the poems remains with the poets and publishers as detailed, and they may not be reproduced without their prior permission. Concept design: Unsworth Shepherd Typesetting: Sarah Elworthy Project co-ordinator: Harley Hern Cover image: Tyler Lastovich on Unsplash (Flooded Jetty) National Poetry Day has been running continuously since 1997 and is celebrated on the last Friday in August. It is administered by the New Zealand Book Awards Trust, and for the past two years has benefited from the wonderful support of street poster company Phantom Billstickers. PAULA GREEN PAGE 20 APIRANA TAYLOR PAGE 17 JENNY BORNHOLDT PAGE 16 Paula Green is a poet, reviewer, anthologist, VINCENT O’SULLIVAN PAGE 22 Apirana Taylor is from the Ngati Porou, Te Whanau a Apanui, and Ngati Ruanui tribes, and also Pakeha Jenny Bornholdt was born in Lower Hutt in 1960 children’s author, book-award judge and blogger. -

Otago University Press 2019 C a T a L O G U E

otago university press 2019 CATALOGUE NEW BOOKS I 1 CONTENTS OTAGO UNIVERSITY PRESS Te Whare Tā o Te Wānanga o Ōtākou New books 3–20 Recent books 21–31 PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand Books in print: by title 32–38 Level 1 / 398 Cumberland Street Books in print: by author 39–41 Dunedin, New Zealand How to buy OUP books 42 Phone: 64 3 479 8807 Email: [email protected] Web: www.otago.ac.nz/press www.facebook.com/OtagoUniversityPress http://twitter.com/OtagoUniPress Co-Publishers: Rachel Scott and Vanessa Manhire Production Manager: Fiona Moffat Editor: Imogen Coxhead Publicity and Marketing Co-ordinator: Victor Billot Accounts Administrator: Arvin Lazaro Prices are recommended retail prices and may be subject to change. Cover: Radclyffe Hall with her dachshunds, from Queer Objects (see pp. 4–5). MSS_HallR_and_ TroubridgeUVL_25/5/004, University of Texas, Austin 2 I NEW BOOKS WOMEN MEAN BUSINESS CATHERINE BISHOP Colonial businesswomen in New Zealand From Kaitaia in Northland to Oban on Stewart Island, New Zealand’s nineteenth- Colonial businesswomen in New Zealand in New businesswomen Colonial Business Mean Women From Kaitaia in Northland to Oban on Stewart Island, New Zealand’s nineteenth- century towns were full of entrepreneurial women.century Contrary towns were full of entrepreneurial to what women. Contrary we to mightwhat we might expect, expect, colonial women were not only wives and mothers or domestic servants. colonial women were not only wives and mothers Aor surprising domestic number ran their own businesses,servants. supporting themselves A surprising and their families, sometimes in productive partnership with husbands, but in other cases number ran their own businesses, supporting themselvescompensating for a spouse’sand incompetence, their intemperance, families, absence – or allsometimes three. -

Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day Celebrate 20 Years with Diverse Poetry Collection

MEDIA RELEASE Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day celebrate 20 years with diverse poetry collection To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day (NPD), 20 leading Kiwi poets were asked to select one of their own poems, something they felt spoke to New Zealanders now. They also chose a poem by an emerging poet, writers they feel make essential reading for us in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection – 40 poems by New Zealand poets who represent the diversity and vibrancy of talent in our contemporary national literature. The list includes Poet Laureates, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards winners, and strong new voices from recent collections and anthologies. NPD has been running continuously since 1997 and is always celebrated on the last Friday in August. Poetry enthusiasts from all over New Zealand organise a feast of events – from poetry slams to flash and pop-up events – in venues that include schools, libraries, bars, galleries, surf clubs, and parks. This year’s NPD will be held on Friday 25 August. Launched today, the 20/20 Collection will be published in groups of ten poems between now and NPD. Featured poets are: Jenny Bornholdt and her pick, Ish Doney; Paula Green and Simone Kaho; Vincent O’Sullivan and Lynley Edmeade; Apirana Taylor and Kiri Piahana Wong; Alison Wong and Chris Tse; Tusiata Avia and Teresia Teaiwa; Kevin Ireland and Gregory Kan; Diana Bridge and John Dennison; Andrew Johnston and Bill Nelson; Michael Harlow and Paul Schimmel; C.K. Stead and Johanna Emeney; David Eggleton and Leilani Tamu; Elizabeth Smither and Rob Hack; Richard Reeve and Michael Steven; Robert Sullivan and Ngahuia Te Awekotuku; Bill Manhire and Louise Wallace; Selina Tusitala Marsh and Reihana Robinson; Cilla McQueen and David Holmes; James Norcliffe and Marisa Capetta; and Brian Turner and Jillian Sullivan. -

MODERN LETTERS Te P¯U Tahi Tuhi Auaha O Te Ao

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯u tahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 9 August 2006 This is the 91st in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Iowa Workshop (i): Starting and building a novel............................................. 1 2. Jack Lasenby Award ........................................................................................... 2 3. The expanding bookshelf..................................................................................... 2 4. New Zealand Book Month — and the festivals beforehand............................... 2 5. Curious questions ................................................................................................ 3 6. Creating Gallipoli ................................................................................................ 3 7. From the whiteboard........................................................................................... 3 8. August – the most poetic month?........................................................................ 4 9. But wait, there’s more… ..................................................................................... 4 10. Recent web reading............................................................................................ 5 11. Great lists of our time........................................................................................ 6 _____________________________________________________________________ -

Newsletter – 2 February 2007

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 26 Aug 2009 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 145th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Alistair Te Ariki Campbell (1925 -2009) ...............................................................1 2. Dr Barbara Anderson..............................................................................................2 3. Hugh Price: learning to read ..................................................................................2 4. Aesthletics .................................................................................................................3 5. New Zealand Post National Schools Poetry Awards and Writing Festival ........3 6. Books and change.....................................................................................................3 7. The expanding bookshelf.........................................................................................4 8. Legal fiction ..............................................................................................................4 9. On stage.....................................................................................................................4 10. Kenyan playwright speaks at Victoria.................................................................4 11. Fantastic Voyages: Writing Speculative Fiction .................................................5 -

Spirituality, Identity and Landscape in Pakeha Literary Fiction, 1975-2009

THE CLOAK OF BEFORE, THE WRENCH / OF BEYOND: SPIRITUALITY, IDENTITY AND LANDSCAPE IN PAKEHA LITERARY FICTION, 1975-2009 BY LISA EYRE A Thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies School of Art History, Classics and Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2012 ! ! CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................................................................iv ABSTRACT .........................................................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE: METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................8 A Literary Methodology..................................................................................................................8 What is “Pakeha literature”?........................................................................................................ 14 Identifying Pakeha writers ........................................................................................................... 18 Defining Landscape...................................................................................................................... 24 CHAPTER TWO: A SECULAR LANDSCAPE...................................................................... -

Literary and Theatre Sources at the Hocken Collections

Reference Guide Literary and Theatre Sources at the Hocken Collections New Zealand poet and Landfall editor Charles Brasch, 1937. Charles Brasch papers, MS-0996- 012/654, S09-539a, Archives & Manuscripts collection. Hocken Collections/Te Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to New Zealand literature and theatre held at the Hocken. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. The advanced search ‐ https://goo.gl/HVNTqH gives you several search options, and you can refine your results to the Hocken Library on the left side of the screen. -

David Eggleton Named New Zealand Poet Laureate 2019-2021

23 August, 2019 - 07:00 Tautai Pacific Arts Trust Accomplished Pacific poet, editor, art critic and journalist David Eggleton has been awarded the New Zealand Poet Laureate 2019 - 2021. David Eggleton is of Rotuman, Tongan and Palagi descent. He grew up in Fiji and South Auckland, and now lives in Dunedin. The National Library has announced his two-year term as poet laureate starts today, which is National Poetry Day. Fuseworks Media The National Library of New Zealand is delighted to announce that David Eggleton of Dunedin is the New Zealand Poet Laureate for 2019 - 2021. Chris Szekely, Chief Librarian of the Alexander Turnbull Library describes David’s appointment as further recognition for "a poet of consequence whose work continues to develop and mature. David is a significant and widely-respected voice in New Zealand poetry whose work is representative of life in Aotearoa in all its breadth and diversity." Former New Zealand Poet Laureate Cilla McQueen says David’s poetry is "informed with indigenous understanding and discerns the post-colonial legacy with a satirist’s sharp eye for humour and incongruity." Says David Eggleton on receiving news of his appointment as Poet Laureate, "I am humbled, honoured and delighted to have been chosen as the new Poet Laureate. I look forward to helping promote and celebrate the importance and need for all kinds of poetry in Aotearoa New Zealand." From its beginnings as the Te Mata Estate Laureate Award in 1996 through to 2007 the Laureates were Bill Manhire, Hone Tuwhare, Elizabeth Smither, Brian Turner and Jenny Bornholdt. Since 2007, when the National Library took over the appointment of the Poet Laureate, the Laureates have been Michele Leggott, Cilla McQueen, Ian Wedde, Vincent O’Sullivan, CK Stead and Selina Tusitala Marsh.