Ka Mate Ka Ora: a New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NZSA Bulletin of New Zealand Studies

NZSA Bulletin of New Zealand Studies Issue Number 2 Edited by Ian Conrich ISSN 1758-8626 Published 2010 by Kakapo Books 15 Garrett Grove, Clifton Village, Nottingham NG11 8PU © 2010 Kakapo Books © 2010 for the poetry, which remains with the authors. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise, or stored in an information retrieval system without written permission from the publisher. Editor: Ian Conrich Assistant Editor: Tory Straker Typesetter: Opuscule Advisory Board: Dominic Alessio (Richmond The American International University) Clare Barker (University of Birmingham) Kezia Barker (Birkbeck, University of London) Claudia Bell (University of Auckland, New Zealand) Judy Bennett (University of Otago, New Zealand) Roger Collins ( Dunedin, New Zealand) Sean Cubitt (University of Melbourne, Australia) Peter Gathercole (Darwin College, University of Cambridge) Nelly Gillet (University of Technology of Angoulême, France) Manying Ip (University of Auckland, New Zealand) Michelle Keown (University of Edinburgh) Yvonne Kozlovsky-Golan (Sapir Academic College, Israel) Geoff Lealand (University of Waikato, New Zealand) Martin Lodge (University of Waikato, New Zealand) Bill Manhire (Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand) Rachael Morgan (Edinburgh) Michaela Moura-Koçuglu (Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany) David Newman (Simon Fraser University, Canada) Claudia Orange (Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand) Vincent O’Sullivan (Victoria University of Wellington, -

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

Office for Contemporary Art Norway / Valiz

and Criticism and Indigenous Art, Curation Sovereign Words. Sovereign Words García-Antón Katya by Edited Tripura. Bikash Sontosh Tripura, Prashanta Tamati-Quennell, Megan Garneau, Biung Ismahasan, Kimberley Moulton, Máret Ánne Sara, Venkat Raman Singh Shyam, Irene Snarby, ÁndeDaniel Somby, Browning, Kabita Chakma, Megan Cope, Santosh Kumar Das, Hannah Donnelly, Léuli Māzyār Luna’i Eshrāghi, David Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism Office for Contemporary Art Norway / Valiz With this publication we pay respect to our peers in Sápmi, as well as to the myriad Indigenous histories, presents and futures harboured in lands and oceans across the world. We acknowledge their Ancestors and the stories of survivance (survival, resistance and presence) in the face of colonial mechanisms that are still ongoing. We also honour the agency possible in the constitution of alliances between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities within the fields of culture and beyond. Sovereign Words. Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism Edited by Katya García-Antón Office for Contemporary Art Norway Valiz, Amsterdam – 2018 7 Preface Katya García-Antón Sounding the Global Sovereign Histories Indigenous. Language, of the Visual Contemporaneity and Indigenous Art Writing 15 Can I Get a Witness? 63 Jođi lea buoret go oru. Indigenous Art Criticism Better in Motion than at David Garneau Rest. Iver Jåks 33 What Does or Should (1932–2007) ‘Indigenous Art’ Mean? Irene Snarby Prashanta Tripura 77 Toi te kupu, toi te mana, 47 History and Context of toi te whenua. The Madhubani (Mithila) Art Permanence of Language, Santosh Kumar Das Prestige and Land Megan Tamati-Quennell 97 Sovereignty over Representation. Indigenous Cinema in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh Kabita Chakma Statues, Maps, Stories Sovereign World-Building. -

September 2005 Lambton Quay WELLINGTON New Zealand Poetry Society Patrons Dame Fiona Kidman Te Hunga Tito Ruri O Aotearoa Vincent O’Sullivan

Newsletter New Zealand Poetry Society PO Box 5283 September 2005 Lambton Quay WELLINGTON New Zealand Poetry Society Patrons Dame Fiona Kidman Te Hunga Tito Ruri o Aotearoa Vincent O’Sullivan President James Norcliffe With the Assistance of Creative NZ Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa Email [email protected] and Lion Foundation Website ISSN 1176-6409 www.poetrysociety.org.nz NZPS Competition – an insider view at them over Queen’s Birthday Weekend. Then I went to the Post Office. I should have been suspicious when the Our International Poetry Competition has recently door opened too easily. The box was empty, except for concluded for another year. How did you do? Were you a small yellow card. The yellow card is what appears in amongst The Chosen Ones? I wasn’t and, as usual, I your box when there is too much mail. There was a flood. consoled myself with the thought that maybe I’d be in the I received from the Post Shop counter a sack containing 81 anthology again this year. envelopes, about half of them from schools and containing I’ve been entering the NZPS competition for a long multiple entries. For the rest of the week I worked until time, and this year I got to see how it works, after agreeing midnight every night, processing envelopes. Several took to take on the role of competition secretary. The first thing more than 1½ hours each. A few were requests for entry I discovered was that the work starts in November, when forms – too late.The slowest part was twinking out names the anthology is launched and the new competition opens. -

Otago Abroad

Otago poetry on Krakow walls The poetry of Otago alumni writers is shining on Krakow city walls, as part of the UNESCO Cities of Literature Multipoetry Project. Read on to learn more about the poets, and view more images of the poetry beaming in to the heart of Krakow. The eight alumni poets are: Emma Neale Emma is a former Burns Fellows at Otago. She currently teaches Creative Writing in the English Department, and her latest book of poetry Tender Machines has recently been published by University of Otago Press. Hone Tuwhare New Zealand's most distinguished Māori poet, and a former Burns Fellow at Otago. Hone Tuwhare is the people’s poet. He was loved and cher ished by New Zealan ders from all walks of life. A picture of Hone's poem in Krakow is featured below. David Eggleton David is editor of pre-eminent NZ literary journal Landfall, published by University of Otago Press. Landfall is New Zealand's foremost and longest-running arts and literary journal, showcasing new fiction and poetry, as well as biographical and critical essays, and cultural commentary. He recently won the 2015 Janet Frame Literary Trust Award for Poetry. A picture of David's poem in Krakow is featured below. Janet Frame Janet Frame is New Zealand’s most distinguished writer. Among her numerous honours, Frame is a Member of the Order of New Zealand, a Nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature and an Honorary Foreign Member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. She was among ten of New Zealand’s greatest living artists named as Arts Foundation of New Zealand Icon Artists in 2003. -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each. -

City of Literature Vision

1 United Nations Designated Educational, Scientific and UNESCO Creative City Cultural Organization in 2014 This publication was written as part of Dunedin City’s bid for UNESCO City of Literature status in March 2014. Some information has been updated since its publication mid-2015. Thank you to all of the people who contributed to developing Dunedin’s bid and in particular the Steering Team members Bernie Hawke, Noel Waite, Annie Villiers and Liz Knowles. A special thank you also to Eleanor Parker, Michael Moeahu, Lisa McCauley; and Elizabeth Rose and Susan Isaacs from the New Zealand National Commission of UNESCO. ISBN: 978-0-473-32950-1 | PUBLISHED BY: Dunedin Public Libraries 2015 | DESIGNER: Casey Thomas COVER IMAGE: Macandrew Bay, Dunedin by Paul le Comte Olveston Historic Home by Guy Frederick ONE OF THE WORLD’S GREAT SMALL CITIES Otago Harbour by David Steer CONTENTS New Zealand: It's People and Place in the World 7 Multi-cultural Heritage 17 • Books for Children 33 City's Contribution to the Creative City Network 49 • Bookshops 33 • Policy 49 Dunedin's Literary Cultural Assets 19 About Us: Dunedin 11 • Musical Lyricists 35 • International Cooperation and Partnerships 50 • City's Layout and Geographical Area 14 • Te Pukapuka M¯aori – M¯aori Literature 21 • Literature-focused Festivals 35 • A Great City for Writers 23 City of Literature Vision 55 • Population and Economy 14 • Residencies and Awards 25 Dunedin's Creative City Assets 37 • Infrastructure 15 • Impressive Publishing Heritage 28 • Arts and Culture 37 • Municipal/Government Structure 15 • Centre for the Book 29 • Events 41 • Urban Planning, Policy and Strategy 15 • Libraries 31 • Educational Institutes 45 Panoramic of the Steamer Basin, Dunedin by Paul le Comte NEW ZEALAND ITS PEOPLE AND PLACE IN THE WORLD Aotearoa New Zealand. -

YOUNG SCIENTIST of the YEAR Internationalisation the ALUMNUS BEHIND FIREFOX CHAMPION SCULLER SPRING 2006 – Ingenio the University of Auckland Alumni Magazine

THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND ALUMNI MAGAZINE SpRING 2006 SHAPING AUCKLAND YOUNG SCIENTIST OF THE YEAR INTERNatIONALISatION THE ALUMNUS BEHIND FIREFOX CHAMPION SCULLER SPRING 2006 – INGENIO THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND ALUMNI MAGAZINE In this issue . Ingenio – The University of Auckland alumni magazine Spring 2006 ISSN 1176-211X Editor Tess Redgrave Photography Godfrey Boehnke Design/production Ingrid Atvars 5 9 10 32 Publication management and proof reading Bill Williams Advertising manager Don Wilson 4 Letters to the Editor OpINION Editorial contact details Entrepreneurship Ingenio 25 Communications and Marketing UNIVERSITY NEWS The University of Auckland Eminent Mäori professor dies ALUMNI Private Bag 92 019 4 Auckland 1142 New Zealand 5 London Royal Society, NZ Trio, 26 Top fox Ben Goodger Level 10 Fisher Building Primatologist 18 Waterloo Quadrant Auckland 28 News and noticeboard Telephone 64 9 373 7599 Leigh Marine, Long QT syndrome 6 Film-maker Roseanne Liang ext 84149 test, Maurice Wilkins Centre 30 Facsimile 64 9 373 7047 email [email protected] www.auckland.ac.nz/ingenio HISTORY PHILANTHROPY Engineering Chris Bennett How alumni keep in touch 7 32 To ensure that you continue to 8 Education 30 Jean Heywood receive Ingenio, and to subscribe to @auckland, the University’s email 9 Old Government House newsletter for alumni and friends, REGULAR COLUMNS please update your details at: RESEARCH www.alumni.auckland.ac.nz/update 34 Sport Alumni Relations Office 10 Young Scientist The University of Auckland 35 Alumni snapshots 19A Princes Street 12 Shaping Auckland Art Private Bag 92019 36 Auckland 1142 New Zealand Books StRatEGY 37 odfrey Boehnke Telephone 64 9 373 7599 G – ext 82246 18 Internationalisation 38 Student life email [email protected] AGE M www.alumni.auckland.ac.nz I TEACHING Copyright ER V Articles reflect personal opinions O Poetry in transmission C and are not those of The University 22 of Auckland. -

MODERN LETTERS Te P¯U Tahi Tuhi Auaha O Te Ao

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯u tahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 28 March 2008 This is the 121 st in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected] 1. We have a winner!.............................................................................................. 1 2. Life across the Tasman........................................................................................ 2 3. Muldooniana....................................................................................................... 2 4. A Spanish story.................................................................................................... 2 5. And still on the subject of writers’ festivals . .................................................. 3 6. Newsflash ............................................................................................................ 3 7. Best New Zealand Poems.................................................................................... 3 8. From the whiteboard.......................................................................................... 3 9. Writing on the run.............................................................................................. 3 10. Online pioneers ................................................................................................. 3 11. The expanding bookshelf................................................................................. -

Hone Tuwhare's Aroha

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 6 September 2008 Hone Tuwhare’s Aroha Robert Sullivan This issue of Ka Mate Ka Ora is an appreciation of Hone Tuwhare’s poetry containing tributes by some of his friends, fans and fellow writers, as well as scholars outlining different aspects of his widely appreciated oeuvre. It was a privilege to be asked by Murray Edmond to guest-edit this celebration of Tuwhare’s work. I use the term work for Tuwhare’s oeuvre because he was brilliantly and humbly aware of his role as a worker, part of a greater class and cultural struggle. His humility is also deeply Māori, and firmly places him as a rangatira of people and poets. It goes without saying that this tribute acknowledges the passing of a very (which adverb to use here – greatly? hugely? extraordinarily?) significant New Zealand poet, and the first Māori author of a literary collection to be published in English. No Ordinary Sun was published by Blackwood and Janet Paul in September 1964. In September 2008, it is an understatement to say that New Zealand Māori literature in English has spread beyond its national boundaries, and that many writers, Māori and non-Māori, stand on Tuwhare’s shoulders. Having the words ‘ka mate’ and ‘ka ora’ together in this journal’s title, terms borrowed from New Zealand’s most famous poem, the ngeri by the esteemed leader and composer Te Rauparaha, feels appropriate for New Zealand’s most esteemed Māori poet in English. Tuwhare’s poetic – regenerative, sexually active, appetitive, pantheistic myth-referencing, choral-solo, light and shade, regional-personal, historical-immediate, high aesthetic registers mixed with popular vocals, class- conscious, ideologically aware, traditional Māori intersecting with contemporary Māori in English – captures the mauri or life-force and the dark duende of Te Rauparaha’s haka composition as it springs from the earth stamped in live performance. -

HISTORY OR GOSSIP? C.K. STEAD the University of Auckland Free

HISTORY OR GOSSIP? C.K. STEAD The University of Auckland Free Public Lecture Auckland Writers Festival 2019 How do literary history and literary gossip differ? On p. 386 of his biography of Frank Sargeson, Michael King reports that in 1972 Frank ‘had another spirited exchange of letters with Karl Stead when Stead reported that [Charles] Brasch had visited him in Menton.’ I had more or less accused Brasch of being an old fake and asked why everyone was so pious about him. In terms of what it was acceptable to say about Brasch at the time, when he was well known as almost the only wealthy benefactor the Arts in New Zealand had, this was outrageous – and no doubt unfair and unjust. Brasch was a good man who did his best for literature and the visual Arts. But he was irritatingly precious, and snobbish – not the snobbishness of wealth and social status, but of ‘good taste’. He suffered from an overload of discriminations and dismissals – and these had no doubt provoked my ‘spirited’ (to use Michael King’s word) outburst in the letter to Frank. Frank wrote back to me, ‘Look you simply can’t write things like that.’ He reminded me that his correspondence was being bought by the Turnbull Library – in other words his papers were becoming literary history, and if he had not rescued me by sending my letter back, I would have gone on record as having said Bad things about Brasch! King records that my reply was, ‘I wrote to you, Frank, not to the Turnbull Library, or to The Future.’ 1 But this was a reminder that when you put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, if you are an aspirant to literature, you may be committing literary history. -

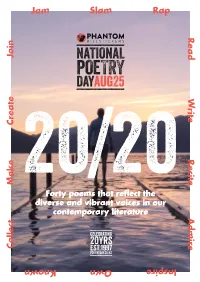

Jam Inspire Create Join Make Collect Slam Own Rap Known Read W Rite

Jam Slam Rap Read Join Write Create Recite Make 20/20 Forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant voices in our contemporary literature Admire Collect Inspire Known Own 20 ACCLAIMED KIWI POETS - 1 OF THEIR OWN POEMS + 1 WORK OF ANOTHER POET To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, we asked 20 acclaimed Kiwi poets to choose one of their own poems – a work that spoke to New Zealand now. They were also asked to select a poem by another poet they saw as essential reading in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection, a selection of forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant range of voices in New Zealand’s contemporary literature. Published in 2017 by The New Zealand Book Awards Trust www.nzbookawards.nz Copyright in the poems remains with the poets and publishers as detailed, and they may not be reproduced without their prior permission. Concept design: Unsworth Shepherd Typesetting: Sarah Elworthy Project co-ordinator: Harley Hern Cover image: Tyler Lastovich on Unsplash (Flooded Jetty) National Poetry Day has been running continuously since 1997 and is celebrated on the last Friday in August. It is administered by the New Zealand Book Awards Trust, and for the past two years has benefited from the wonderful support of street poster company Phantom Billstickers. PAULA GREEN PAGE 20 APIRANA TAYLOR PAGE 17 JENNY BORNHOLDT PAGE 16 Paula Green is a poet, reviewer, anthologist, VINCENT O’SULLIVAN PAGE 22 Apirana Taylor is from the Ngati Porou, Te Whanau a Apanui, and Ngati Ruanui tribes, and also Pakeha Jenny Bornholdt was born in Lower Hutt in 1960 children’s author, book-award judge and blogger.