A Note on the Contributions of Wilson Duff to Northwest Coast Ethnology and Art MICHAEL M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-War Anthropology Andrew Nurse

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 17:02 Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine The Ambiguities of Disciplinary Professionalization: The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-war Anthropology Andrew Nurse Volume 30, numéro 2, 2007 Résumé de l'article La professionnalisation de l’anthropologie canadienne dans la première moitié URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800546ar du 20e siècle fut étroitement liée à la matrice de l’État fédéral, tout d’abord par DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/800546ar l’entremise de la division anthropologique de la Comission géologique du Canada, et ensuite par le biais du Musée national. Les anthropologues de l’État Aller au sommaire du numéro possèdent alors un statut professionnel ambigu à la fois comme fonctionnaires et comme anthropologues dévoués aux impératifs méthodologiques et disciplinaires de la science sociale moderne, mais limités et guidés par les Éditeur(s) exigences du service civil. Leur position au sein de l’État a favorisé le développement de la discipline, mais a également compromis l’autonomie CSTHA/AHSTC disciplinaire. Pour faire face aux limites imposées par l’État au soutien de leur discipline, les anthropologues de la fonction publique ont entretenu différents ISSN réseaux culturels, intellectuels, et comercialement-orientés qui ont servi à soutenir les nouveaux développements de leur champ, particulièrement dans 0829-2507 (imprimé) l’étude du folklore. Le présent essai examine ces dynamiques et suggère que le 1918-7750 (numérique) développement disciplinaire de l’anthropologie ne crée pas de dislocations entre la recherche professionnelle et la société civile. -

The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-War Anthropology Andrew Nurse

Document generated on 09/30/2021 5:47 p.m. Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine The Ambiguities of Disciplinary Professionalization: The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-war Anthropology Andrew Nurse Volume 30, Number 2, 2007 Article abstract The professionalization of Canadian anthropology in the first half of the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800546ar twentieth century was tied closely to the matrix of the federal state, first DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/800546ar though the Anthropology Division of the Geological Survey of Canada and then the National Museum. State anthropologists occupied an ambiguous See table of contents professional status as both civil servants and anthropologists committed to the methodological and disciplinary imperatives of modern social science but bounded and guided by the operation of the civil service. Their position within Publisher(s) the state served to both advance disciplinary development but also compromised disciplinary autonomy. To address the boundaries the state CSTHA/AHSTC imposed on its support for anthropology, state anthropologists cultivated cultural, intellectual, and commercially-oriented networks that served to ISSN sustain new developments in their field, particularly in folklore. This essay examines these dynamics and suggests that anthropology's disciplinary 0829-2507 (print) development did not create a disjunctive between professionalized scholarship 1918-7750 (digital) and civil society. Explore this journal Cite this article Nurse, A. (2007). The Ambiguities of Disciplinary Professionalization: The State and Cultural Dynamics of Canadian Inter-war Anthropology. Scientia Canadensis, 30(2), 37–53. -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

Marian Penner Bancroft Rca Studies 1965

MARIAN PENNER BANCROFT RCA STUDIES 1965-67 UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, Arts & Science 1967-69 THE VANCOUVER SCHOOL OF ART (Emily Carr University of Art + Design) 1970-71 RYERSON POLYTECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, Toronto, Advanced Graduate Diploma 1989 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, Visual Arts Summer Intensive with Mary Kelly 1990 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, short course with Griselda Pollock SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, upcoming in May 2019 WINDWEAVEWAVE, Burnaby, BC, video installation, upcoming in May 2018 HIGASHIKAWA INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL GALLERY, Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan, Overseas Photography Award exhibition, Aki Kusumoto, curator 2017 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, RADIAL SYSTEMS photos, text and video installation 2014 THE REACH GALLERY & MUSEUM, Abbotsford, BC, By Land & Sea (prospect & refuge) 2013 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HYDROLOGIC: drawing up the clouds, photos, video and soundtape installation 2012 VANCOUVER ART GALLERY, SPIRITLANDS t/Here, Grant Arnold, curator 2009 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, CHORUS, photos, video, text, sound 2008 REPUBLIC GALLERY, Vancouver, HUMAN NATURE: Alberta, Friesland, Suffolk, photos, text installation 2001 CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver THE MENDEL GALLERY, Saskatoon SOUTHERN ALBERTA ART GALLERY, Lethbridge, Alberta, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) 2000 GALERIE DE L'UQAM, Montreal, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) CATRIONA JEFFRIES GALLERY, Vancouver, VISIT 1999 PRESENTATION HOUSE GALLERY, North Vancouver, By Land and Sea (prospect and refuge) UNIVERSITY -

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol

THE ARTERY News from the Britannia Art Gallery February 1, 2017 Vol. 44 Issue 97 While the Artery is providing this newsletter as a courtesy service, every effort is made to ensure that information listed below is timely and accurate. However we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of information and functioning of all links. INDEX # ON AT THE GALLERY: Exhibition My Vintage Rubble and Fish & Moose series 1 Mini-retrospective by Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wednesday, Feb 1, 6:30 pm EVENTS AROUND TOWN EVENTS 2-6 EXHIBITIONS 7-24 THEATRE 25/26 WORKSHOPS 27-30 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS LOCAL EXHIBITIONS 31 GRANTS 32 MISCELLANEOUS 33 PUBLIC ART 34 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS NATIONAL AWARDS 35 EXHIBITIONS 36-44 FAIR 45/46 FESTIVAL 47-49 JOB CALL 50-56 CALL FOR PARTICPATION 57 PERFORMANCE 58 CONFERENCE 59 PUBLIC ART 60-63 RESIDENCY 64-69 CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS INTERNATIONAL WEBSITE 70 BY COUNTRY ARGENTINA RESIDENCY 71 AUSTRIA PRIZE 72 BRAZIL RESIDENCY 73/74 CANADA RESIDENCY 75-79 FRANCE RESIDENCY 80/81 GERMANY RESIDENCY 82 ICELAND PERFORMERS 83 INDIA RESIDENCY 84 IRELAND FESTIVAL 85 ITALY FAIR 86 RESIDENCY 87-89 MACEDONIA RESIDENCY 90 MEXICO RESIDENCY 91/92 MOROCCO RESIDENCY 93 NORWAY RESIDENCY 94 PANAMA RESIDENCY 95 SPAIN RESIDENCY 96 RETREAT 97 UK RESIDENCY 98/99 USA COMPETITION 100 EXHIBITION 101 FELLOWSHIP 102 RESIDENCY 103-07 BRITANNIA ART GALLERY: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: 108 SUBMISSIONS TO THE ARTERY E-NEWSLETTER 109 VOLUNTEER RECOGNITION 110 GALLERY CONTACT INFORMATION 111 ON AT BRITANNIA ART GALLERY 1 EXHIBITIONS: February 1 - 24 My Vintage Rubble, Fish and Moose series – Ken Gerberick Opening Reception: Wed. -

PROVINCIAL MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY and ANTHROPOLOGY

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION PROVINCIAL MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY and ANTHROPOLOGY REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1958 Printed by DON MCDIARMID, Printer to the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty in right of the Province of British Columbia. 1959 To His Honour FRANK MACKENZIE ROSS, C.M.G., M.C., LL.D., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology for the year 1958. L. R. PETERSON, Minister of Education. Office of the Minister of Education, January, 1959. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY, VICTORIA, B.C., January 19th, 1959. The Honourable L. R. Peterson, Minister of Education, Victoria, B.C. SIR,—The undersigned respectfully submits herewith a report covering the activities of the Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology for the calendar year 1958. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, G. CLIFFORD CARL, Director. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION The Honourable LESLIE RAYMOND PETERSON, LL.B., Minister. J. F. K. ENGLISH, M.A., Ed.D., Deputy Minister and Superintendent. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY Staff G. CLIFFORD CARL, Ph.D., Director. CHARLES J. GUIGUET, M.A., Curator of Birds and Mammals. WILSON DUFF, M.A., Curator of Anthropology. ADAM F. SZCZAWINSKI, Ph.D., Curator of Botany. J. E. MICHAEL KEW, B.A., Assistant in Anthropology. FRANK L. BEEBE, Illustrator and Museum Technician. MARGARET CRUMMY, B.A., Senior Stenographer. BETTY C. NEWTON, Museum Technician. SHEILA Y. NEWNHAM, Assistant in Museum Technique. -

MAKING HISTORY VISIBLE Culture and Politics in the Presentation of Musqueam History

MAKING HISTORY VISIBLE Culture and Politics in the Presentation of Musqueam History Susan Roy B.A., University of British Columbia. 1993 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFIL,LMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History O Susan Roy I999 SIMON F;RASER UNIVERSlTY November 1999 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Bibliith&que nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prster, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis .nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent itre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT The ongoing struggle for aboriginal rights in British Columbia has been matched by an ongoing attempt on the part of scholars to analyze it. The focus of many of these studies has been the court room, that is, the legaI battles to define aboriginal title and sovereignty. -

Marius Barbeau and Musical Performers Elaine Keillor

Marius Barbeau and Musical Performers Elaine Keillor Abstract: One of Marius Barbeau’s important contributions to heightening awareness of folk music traditions in Canada was his organization and promotion of concerts. These concerts took different forms and involved a range of performers. Concert presentations of folk music, such as those that Barbeau initiated called the Veillées du bon vieux temps, often and typically included a combination of performers. This article examines Barbeau’s “performers,” including classically educated musicians and some of his most prolific, talented informants. Barbeau and Juliette Gaultier Throughout Barbeau’s career as a folklorist, one of his goals was to use trained Canadian classical musicians as folk music performers, thereby introducing Canada’s rich folk music heritage to a broader public. This practice met with some mixed reviews. There are suggestions that he was criticized for depending on an American singer, Loraine Wyman,1 in his early presentations. Certainly, in his first Veillées du bon vieux temps, he used Sarah Fischer (1896-1975), a French-born singer who had made a highly praised operatic debut in 1918 at the Monument national in Montreal. But in 1919, she returned to Europe to pursue her career. Since she was no longer readily available for Barbeau’s efforts, he had to look elsewhere. One of Barbeau’s most prominent Canadian, classically trained singers was Juliette Gauthier de la Verendrye2 (1888-1972). Born in Ottawa, Juliette Gauthier attended McGill University, studied music in Europe, and made her debut with the Boston Opera in the United States. The younger sister of the singer Eva Gauthier,3 Juliette Gauthier made her professional career performing French, Inuit, and Native music. -

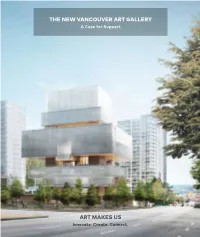

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY a Case for Support

THE NEW VANCOUVER ART GALLERY A Case for Support A GATHERING PLACE for Transformative Experiences with Art Art is one of the most meaningful ways in which a community expresses itself to the world. Now in its ninth decade as a significant contributor The Gallery’s art presentations, multifaceted public to the vibrant creative life of British Columbia and programs and publication projects will reflect the Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery has embarked on diversity and vitality of our community, connecting local a transformative campaign to build an innovative and ideas and stories within the global realm and fostering inspiring new art museum that will greatly enhance the exchanges between cultures. many ways in which citizens and visitors to the city can experience the amazing power of art. Its programs will touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, through remarkable, The new building will be a creative and cultural mind-opening experiences with art, and play a gathering place in the heart of Vancouver, unifying substantial role in heightening Vancouver’s reputation the crossroads of many different neighbourhoods— as a vibrant place in which to live, work and visit. Downtown, Yaletown, Gastown, Chinatown, East Vancouver—and fuelling a lively hub of activity. For many British Columbians, this will be the most important project of their Open to everyone, this will be an urban space where museum-goers and others will crisscross and encounter generation—a model of civic leadership each other daily, and stop to take pleasure in its many when individuals come together to build offerings, including exhibitions celebrating compelling a major new cultural facility for its people art from the past through to artists working today— and for generations of children to come. -

New Year's in Vancouver

NEW YEAR’S IN Activity Level: 1 VANCOUVER December 30, 2021 – 4 Days 1 Dinner Included With Salute to Vienna concert at Orpheum Fares per person: $1,470 double/twin; $1,825 single; $1,420 triple Please add 5% GST. Ring in 2022 in style and enjoy the annual performance of Salute to Vienna presented Early Bookers: $60 discount on first 15 seats; $30 on next 10 by the Vancouver Symphony. It has an Experience Points: outstanding cast of 75 musicians, singers, Earn 32 points on this tour. and dancers, and has been billed as the Redeem 32 points if you book by October 27, 2021. world’s greatest New Year’s concert. We Departure from: Victoria have reserved superb seats in the Centre Orchestra of the Orpheum Theatre. Two other shows are also included, but most theatre companies are still emerging from Covid shutdowns and planning their fall and winter schedules. A morning at the Vancouver Art Gallery is included. The tour stays 3 nights at the renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver. Salute to Vienna ITINERARY Day 1: Thursday, December 30 such as the Gateway or Granville Island Stage. Transportation is provided mid-day to the Again, if you are not interested in attending, you renowned Fairmont Hotel Vancouver and we stay can opt out and your fare will be reduced. We three nights. Opened in 1939 at a cost of $12 return to the hotel after the show, then at million, it was the third Hotel Vancouver and a midnight you may want to celebrate the arrival of downtown landmark with its copper green roof 2022 in the hotel lounge or nearby. -

The Cult of the Folk: Ideas and Strategies After Ernest Gagnon Gordon E

Document generated on 10/01/2021 7:19 a.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes The Cult of the Folk: Ideas and Strategies after Ernest Gagnon Gordon E. Smith Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Article abstract Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie In this paper I discuss ideas of collectors (Édouard-Zotique Massicotte and Volume 19, Number 2, 1999 Marius Barbeau) vis-à-vis the song collection of Ernest Gagnon. The Chansons populaires repertoire is viewed in different ways by Gagnon's successors as URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014443ar historically significant and/or insignificant, and/or an exhaustive, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014443ar representative "canon" of songs. Approaches to fieldwork, transcription, and the "selection" of repertoire in these collectors' works are also studied. The second part of the paper sets up a critical frame of reference for these See table of contents strategies based on current literature (e.g., Philip Bohlman, Ian MacKay). Within this discussion, Gagnon's nineteenth-century ideology of "le peuple" is considered alongside the preservationist "cult of the folk" inspiration of his Publisher(s) successors. Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (print) 2291-2436 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Smith, G. E. (1999). The Cult of the Folk: Ideas and Strategies after Ernest Gagnon. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014443ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. -

Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Potlatch at Gitsegukla

n8 BC STUDIES ... I had been thinking about the book is aimed, will be able to critically glyphs all morning after finally being assess its lack of scholarship. This can ferried across" Too bad he didn't take only lead to entrenching preconceptions the time to speak with the Edgars, who about, and ignorance of, First Nations have intimate knowledge of the area in British Columbia. The sad thing is and the tliiy'aa'a of Clo-oose. that, although this result is no doubt Serious students will find little of the furthest thing from Johnson's value in this book, and it is unlikely intention, it will be the legacy of his that the general public, at whom the book. Transmission Difficulties: Franz Boas and Tsimshian Mythology Ralph Maud Burnaby: Talonbooks, 2000.174 pp. Illus. $16.95 paper. Potlatch at Gitsegukla: William Beynon's 1Ç45 Field Notebooks Margaret Anderson and Marjorie Halpin, Editors Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000. 283 pp. Illus., maps. $29.95 paper. REGNA DARNELL University of Western Ontario OTH VOLUMES REVIEWED here respects the integrity of Beynon's parti explore the present utility and cipant-observation documentation, B quality of Tsimshian archival simultaneously reassessing and con- and published materials. There the re textualizing it relative to other extant semblance ends. The scholarly methods work on the Gitksan and closely related and standpoints are diametrically op peoples. Beynon was invited to the pot- posed; a rhetoric of continuity and latches primarily in his chiefly capacity, respect for tradition contrasts sharply although he was also an ethnographer with one of revolutionary discontinuity.