Which Voting System Is Best for Canada?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single-Winner Voting Method Comparison Chart

Single-winner Voting Method Comparison Chart This chart compares the most widely discussed voting methods for electing a single winner (and thus does not deal with multi-seat or proportional representation methods). There are countless possible evaluation criteria. The Criteria at the top of the list are those we believe are most important to U.S. voters. Plurality Two- Instant Approval4 Range5 Condorcet Borda (FPTP)1 Round Runoff methods6 Count7 Runoff2 (IRV)3 resistance to low9 medium high11 medium12 medium high14 low15 spoilers8 10 13 later-no-harm yes17 yes18 yes19 no20 no21 no22 no23 criterion16 resistance to low25 high26 high27 low28 low29 high30 low31 strategic voting24 majority-favorite yes33 yes34 yes35 no36 no37 yes38 no39 criterion32 mutual-majority no41 no42 yes43 no44 no45 yes/no 46 no47 criterion40 prospects for high49 high50 high51 medium52 low53 low54 low55 U.S. adoption48 Condorcet-loser no57 yes58 yes59 no60 no61 yes/no 62 yes63 criterion56 Condorcet- no65 no66 no67 no68 no69 yes70 no71 winner criterion64 independence of no73 no74 yes75 yes/no 76 yes/no 77 yes/no 78 no79 clones criterion72 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 monotonicity yes no no yes yes yes/no yes criterion80 prepared by FairVote: The Center for voting and Democracy (April 2009). References Austen-Smith, David, and Jeffrey Banks (1991). “Monotonicity in Electoral Systems”. American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, No. 2 (June): 531-537. Brewer, Albert P. (1993). “First- and Secon-Choice Votes in Alabama”. The Alabama Review, A Quarterly Review of Alabama History, Vol. ?? (April): ?? - ?? Burgin, Maggie (1931). The Direct Primary System in Alabama. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

Automated Verification for Functional and Relational Properties of Voting

Automated Verification for Functional and Relational Properties of Voting Rules Bernhard Beckert, Thorsten Bormer, Michael Kirsten, Till Neuber, and Mattias Ulbrich Abstract In this paper, we formalise classes of axiomatic properties for voting rules, discuss their characteristics, and show how symmetry properties can be exploited in the verification of other properties. Following that, we describe how automated verification methods such as software bounded model checking and deductive verification can be used to verify implementations of voting rules. We present a case study, where we use and compare different approaches to verify that plurality voting satisfies the majority and the anonymity property. 1 Introduction Axiomatic definitions of characteristic properties for voting rules are important both for understanding existing voting rules and for designing new ones. For the trustworthiness of elections, it is also important to analyse the algorithmic descriptions of voting rules and to prove that they have the desired properties, i.e., they satisfy the declarative description. There are two classes of voting rule properties, namely (a) functional (absolute) properties, such as the majority criterion, which refer to single voting results, and (b) relational properties, such as anonymity, which are defined by comparing two (or more) results. In this paper, we first formally define these two classes of properties and discuss their characteristics (Section 2). We then show how symmetry properties { which are a particular kind of relational properties { can be exploited to more efficiently verify voting rules w.r.t. other (functional) properties (Section 3). Proving properties of voting rules by hand is tedious and error-prone { in particular, if the rules and properties evolve during design and various versions have to be verified. -

Voting Systems∗

Voting Systems∗ Paul E. Johnson May 27, 2005 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Mathematical concepts 4 2.1 Transitivity. 4 2.2 Ordinal versus Cardinal Preferences . 5 3 The Plurality Problem 7 3.1 Two Candidates? No Problem! . 7 3.2 Shortcomings of Plurality Rule With More than Two Candidates . 9 4 Rank-order voting: The Borda Count 14 4.1 The Borda Count . 15 4.2 A Paradox in the Borda Procedure . 17 4.3 Another Paradox: The Borda Winner Is A Loser? . 20 4.4 Inside the Guts of the Borda Count . 21 ∗This is a chapter prepared for educational usage by undergraduates at the University of Kansas and for eventual inclusion in a mathematics textbook that is being written with Saul Stahl of the University of Kansas Department of Mathematics. Revisions will be ongoing, so comments & corrections are especially welcome. Please contact Paul Johnson <[email protected]>. 1 4.5 Digression on the Use of Cardinal Preferences . 25 5 Sequential Pairwise Comparisons 28 5.1 A Single Elimination Tournament . 28 5.2 Dominated Winner Paradox . 30 5.3 The Intransitivity of Majority Rule . 30 6 Condorcet Methods: The Round Robin Tournament 35 6.1 Searching for an Unbeatable Set of Alternatives . 36 6.2 The Win-Loss Record . 37 6.3 Aggregated Pairwise Voting: The Borda Count Strikes Back! . 38 6.4 The Schulze Method . 43 7 Single Vote Systems: Cousins of Plurality and Majority Rule 57 8 Conclusion 63 List of Figures 1 Hypothetical Football Tournament . 29 2 Tournament Structure for the Dominated Winner Paradox . 31 3 The Smith Set . -

Crowdsourcing Applications of Voting Theory Daniel Hughart

Crowdsourcing Applications of Voting Theory Daniel Hughart 5/17/2013 Most large scale marketing campaigns which involve consumer participation through voting makes use of plurality voting. In this work, it is questioned whether firms may have incentive to utilize alternative voting systems. Through an analysis of voting criteria, as well as a series of voting systems themselves, it is suggested that though there are no necessarily superior voting systems there are likely enough benefits to alternative systems to encourage their use over plurality voting. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 Assumptions ............................................................................................................................... 6 Voting Criteria .............................................................................................................................. 10 Condorcet ................................................................................................................................. 11 Smith ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Condorcet Loser ........................................................................................................................ 15 Majority ................................................................................................................................... -

The Space of All Proportional Voting Systems and the Most Majoritarian Among Them

Social Choice and Welfare https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-018-1166-9 ORIGINAL PAPER The space of all proportional voting systems and the most majoritarian among them Pietro Speroni di Fenizio1 · Daniele A. Gewurz2 Received: 10 July 2017 / Accepted: 30 November 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract We present an alternative voting system that aims at bridging the gap between pro- portional representative systems and majoritarian electoral systems. The system lets people vote for multiple party-lists, but then assigns each ballot paper to a single party. This opens a whole range of possible parliaments, all proportionally representative. We show theoretically that this space is convex. Then among the possible parliaments we present an algorithm to produce the most majoritarian result. We then test the system and compare the results with a pure proportional and a majoritarian voting system showing how the results are comparable with the majoritarian system. Then we simulate the system and show how it tends to produce parties of exponentially decreasing size with always a first, major party with about half of the seats. Finally we describe how the system can be used in the context of a parliament made up of two separate houses. 1 Introduction One of the main difficulties in choosing an electoral systems is how to approach the dichotomy between governability and representativeness. The general consensus is that it is impossible to have a system that is both proportionally representative and that assures a sufficient concentration of power in few parties to give them the possibility to efficiently govern a country. -

The Expanding Approvals Rule: Improving Proportional Representation and Monotonicity 3

Working Paper The Expanding Approvals Rule: Improving Proportional Representation and Monotonicity Haris Aziz · Barton E. Lee Abstract Proportional representation (PR) is often discussed in voting settings as a major desideratum. For the past century or so, it is common both in practice and in the academic literature to jump to single transferable vote (STV) as the solution for achieving PR. Some of the most prominent electoral reform movements around the globe are pushing for the adoption of STV. It has been termed a major open prob- lem to design a voting rule that satisfies the same PR properties as STV and better monotonicity properties. In this paper, we first present a taxonomy of proportional representation axioms for general weak order preferences, some of which generalise and strengthen previously introduced concepts. We then present a rule called Expand- ing Approvals Rule (EAR) that satisfies properties stronger than the central PR axiom satisfied by STV, can handle indifferences in a convenient and computationally effi- cient manner, and also satisfies better candidate monotonicity properties. In view of this, our proposed rule seems to be a compelling solution for achieving proportional representation in voting settings. Keywords committee selection · multiwinner voting · proportional representation · single transferable vote. JEL Classification: C70 · D61 · D71 1 Introduction Of all modes in which a national representation can possibly be constituted, this one [STV] affords the best security for the intellectual qualifications de- sirable in the representatives—John Stuart Mill (Considerations on Represen- tative Government, 1861). arXiv:1708.07580v2 [cs.GT] 4 Jun 2018 H. Aziz · B. E. Lee Data61, CSIRO and UNSW, Sydney 2052 , Australia Tel.: +61-2-8306 0490 Fax: +61-2-8306 0405 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Haris Aziz, Barton E. -

Selecting the Runoff Pair

Selecting the runoff pair James Green-Armytage New Jersey State Treasury Trenton, NJ 08625 [email protected] T. Nicolaus Tideman Department of Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] This version: May 9, 2019 Accepted for publication in Public Choice on May 27, 2019 Abstract: Although two-round voting procedures are common, the theoretical voting literature rarely discusses any such rules beyond the traditional plurality runoff rule. Therefore, using four criteria in conjunction with two data-generating processes, we define and evaluate nine “runoff pair selection rules” that comprise two rounds of voting, two candidates in the second round, and a single final winner. The four criteria are: social utility from the expected runoff winner (UEW), social utility from the expected runoff loser (UEL), representativeness of the runoff pair (Rep), and resistance to strategy (RS). We examine three rules from each of three categories: plurality rules, utilitarian rules and Condorcet rules. We find that the utilitarian rules provide relatively high UEW and UEL, but low Rep and RS. Conversely, the plurality rules provide high Rep and RS, but low UEW and UEL. Finally, the Condorcet rules provide high UEW, high RS, and a combination of UEL and Rep that depends which Condorcet rule is used. JEL Classification Codes: D71, D72 Keywords: Runoff election, two-round system, Condorcet, Hare, Borda, approval voting, single transferable vote, CPO-STV. We are grateful to those who commented on an earlier draft of this paper at the 2018 Public Choice Society conference. 2 1. Introduction Voting theory is concerned primarily with evaluating rules for choosing a single winner, based on a single round of voting. -

The Plurality-With-Elimination Method (PWE)

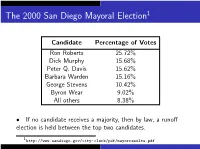

The 2000 San Diego Mayoral Election1 Candidate Percentage of Votes Ron Roberts 25.72% Dick Murphy 15.68% Peter Q. Davis 15.62% Barbara Warden 15.16% George Stevens 10.42% Byron Wear 9.02% All others 8.38% • If no candidate receives a majority, then by law, a runoff election is held between the top two candidates. 1http://www.sandiego.gov/city-clerk/pdf/mayorresults.pdf Example: The 2000 San Diego Mayoral Election Practical problems with this system: I Runoff elections cost time and money I Ties (or near-ties) for second place I Preference ballots provide a method of holding an “instant-runoff" election: the Plurality-with-Elimination Method (PWE). 2. If no candidate has received a majority, then eliminate the candidate with the fewest first-place votes. 3. Repeat steps 1 and 2 until some candidate has a majority, then declare that candidate the winner. The Plurality-with-Elimination Method (x1.4) 1. Count the first-place votes. If some candidate receives a majority of the first-place votes, then that candidate is the winner. 3. Repeat steps 1 and 2 until some candidate has a majority, then declare that candidate the winner. The Plurality-with-Elimination Method (x1.4) 1. Count the first-place votes. If some candidate receives a majority of the first-place votes, then that candidate is the winner. 2. If no candidate has received a majority, then eliminate the candidate with the fewest first-place votes. The Plurality-with-Elimination Method (x1.4) 1. Count the first-place votes. If some candidate receives a majority of the first-place votes, then that candidate is the winner. -

10. Dalton Et Al. Pp.124-38.Pmd

ADVANCED DEMOCRACIES AND THE NEW POLITICS Russell J. Dalton, Susan E. Scarrow, and Bruce E. Cain Russell J. Dalton is director of the Center for the Study of Democracy at the University of California, Irvine. Susan E. Scarrow is associate professor of political science at the University of Houston. Bruce E. Cain is Robson Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, and director of the Institute of Governmental Studies. This essay is adapted from their edited volume, Democracy Transformed? Expanding Political Opportunities in Advanced Indus- trial Democracies (2003). Over the past quarter-century in advanced industrial democracies, citi- zens, public interest groups, and political elites have shown decreasing confidence in the institutions and processes of representative govern- ment. In most of these nations, electoral turnout and party membership have declined, and citizens are increasingly skeptical of politicians and political institutions.1 Along with these trends often go louder demands to expand citizen and interest-group access to politics, and to restructure democratic deci- sion-making processes. Fewer people may be voting, but more are signing petitions, joining lobby groups, and engaging in unconventional forms of political action.2 Referenda and ballot initiatives are growing in popu- larity; there is growing interest in processes of deliberative or consultative democracy;3 and there are regular calls for more reliance on citizen advi- sory committees for policy formation and administration—especially at the local level, where direct involvement is most feasible. Contempo- rary democracies are facing popular pressures to grant more access, increase the transparency of governance, and make government more accountable. -

Chapter 3 Voting Systems

Chapter 3 Voting Systems 3.1 Introduction We rank everything. We rank movies, bands, songs, racing cars, politicians, professors, sports teams, the plays of the day. We want to know “who’s number one?” and who isn't. As a lo- cal sports writer put it, “Rankings don't mean anything. Coaches continually stress that fact. They're right, of course, but nobody listens. You know why, don't you? People love polls. They absolutely love ’em” (Woodling, December 24, 2004, p. 3C). Some rankings are just for fun, but people at the top sometimes stand to make a lot of money. A study of films released in the late 1970s and 1980s found that, if a film is one of the 5 finalists for the Best Picture Oscar at the Academy Awards, the publicity generated (on average) generates about $5.5 mil- lion in additional box office revenue. Winners make, on average, $14.7 million in additional revenue (Nelson et al., 2001). In today's inflated dollars, the figures would no doubt be higher. Actors and directors who are nominated (and who win) should expect to reap rewards as well, since the producers of new films are eager to hire Oscar-winners. This chapter is about the procedures that are used to decide who wins and who loses. De- veloping a ranking can be a tricky business. Political scientists have, for centuries, wrestled with the problem of collecting votes and moulding an overall ranking. To the surprise of un- 1 CHAPTER 3. VOTING SYSTEMS 2 dergraduate students in both mathematics and political science, mathematical concepts are at the forefront in the political analysis of voting procedures. -

Arrow's Impossibility Theorem

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem Some announcements • Final reflections due on Monday. • You now have all of the methods and so you can begin analyzing the results of your election. Today’s Goals • We will discuss various fairness criteria and how the different voting methods violate these criteria. Last Time We have so far discussed the following voting methods. • Plurality Method (Majority Method) • Borda Count Method • Plurality-with-Elimination Method (IRV) • Pairwise Comparison Method • Method of Least Worst Defeat • Ranked Pairs Method • Approval Voting Fairness Criteria The following fairness criteria were developed by Kenneth Arrow, an economist in the 1940s. Economists are often interested in voting theories because of their impact on game theory. The mathematician John Nash (the subject of A Beautiful Mind) won the Nobel Prize in economics for his contributions to game theory. The Majority Criterion A majority candidate should always be the winner. Note that this does not say that a candidate must have a majority to win, only that such a candidate should not lose. Plurality, IRV, Pairwise Comparison, LWD, and Ranked Pairs all satisfy the Majority Criterion. The Majority Criterion The Borda Count Method violates the Majority Criterion. Number of voters 6 2 3 1st A B C 2nd B C D 3rd C D B 4th D A A Even though A had a majority of votes it only has 29 points. B is the winner with 32 points. Moral: Borda Count punishes polarizing candidates. The Condorcet Criterion A Condorcet candidate should always be the winner. Recall that a Condorcet Candidate is one that beats all other candidates in a head-to-head (pairwise) comparison.