The Relationship Between Protected Areas and Indigenous Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Vegetation Data from the Prioksko-Terrasnyi Biosphere Reserve

Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e71266 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.9.e71266 Data Paper Current vegetation data from the Prioksko- Terrasnyi Biosphere Reserve Mikhail Shovkun‡, Natalya Ivanova§§, Larisa Khanina , Michael S. Romanov§‡, Vasily Demidov ‡ Prioksko-Terrasnyi Biosphere Reserve, Danki, Russia § Institute of Mathematical Problems of Biology RAS – branch of the Keldysh Institute of Applied Mathematics of Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino, Russia Corresponding author: Mikhail Shovkun ([email protected]), Natalya Ivanova ([email protected]), Larisa Khanina ([email protected]), Vasily Demidov ([email protected]) Academic editor: Ivan Chadin Received: 08 Jul 2021 | Accepted: 17 Aug 2021 | Published: 25 Aug 2021 Citation: Shovkun M, Ivanova N, Khanina L, Romanov MS, Demidov V (2021) Current vegetation data from the Prioksko-Terrasnyi Biosphere Reserve. Biodiversity Data Journal 9: e71266. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.9.e71266 Abstract Background Here we present the sampling event dataset that contributes to the knowledge of current vegetation of the Prioksko-Terrasnyi Biosphere Reserve (part of the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves), Moscow Region, Russia. The Reserve is situated on the terraces of the Oka River in the zone of mixed coniferous forests. New information The dataset provides 269 relevés (9174 associated occurrences) of renewed vegetation collected in 2019-2020. It is aimed at sampling vegetation data from the Reserve area with particular interest to sites with invasive species and sites with recent deadfall in the spruce stands caused by the bark beetle-typographer. The dataset contains representative information on plant communities in localities with assigned GPS coordinates, sampled using the standard relevé method with the Braun-Blanquet cover-abundance scale. -

Nature Reserve of Orange County

NATURE RESERVE OF ORANGE COUNTY NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release June 13, 2016 Irvine, California-- Between June 18 to June 24 and July 5 to July 12, the Nature Communities Coalition (NCC), in collaboration with OC Parks, Irvine Ranch Conservancy, and The Nature Conservancy will conduct an aerial weed survey during daylight hours using a small, low-flying helicopter to document and map the distribution of over 30 weed species located within selected inland parks and open space areas. The resulting information will provide details about the abundance and distribution of invasive weeds and help land managers evaluate the effectiveness of current weed monitoring practices, identify emerging weed problems, and strategically plan future weed management actions. Notices describing the aerial weed survey will be posted at trailheads at participating parks and open space areas during the project period. The aerial weed survey will be focused on mapping the distribution of artichoke thistle and a minimum of 30 other established and emerging invasive weeds which degrade natural habitat values important to wildlife and the park visitor experience. The survey will cover nearly 32,000 acres and involve the following land areas (also see attached map): Aerial Survey Area Ownership Whiting Ranch Wilderness Park OC Parks Siphon Reservoir Irvine Ranch Water District City of Irvine Open Space Preserve North City of Irvine Irvine Ranch Open Space OC Parks Irvine Regional Park OC Parks Peters Canyon Regional Park OC Parks Santiago Oaks Regional Park OC Parks Coal Canyon Ecological Reserve California Department of Fish and Wildlife -OVER- The aerial survey will be conducted by an experienced team, Wildlands Conservation Science LLC, using a small helicopter (Schweizer-333) and a crew of three (an experienced pilot and two biologists conducting the survey). -

Bay Road Park Local Nature Reserve

Bay Road Park Local Nature Reserve www.derrycity.gov.uk/biodiversity Bay Road Park Local Nature Reserve is a 20 ha former landfill site, located on the banks of the River Foyle, which provides impressive scenery of the Foyle Bridge, Foyle catchment and the City. It can Bay Road Park supports a wide range of habitats to include woodland, grassland, salt be accessed from the Foyle marsh and mudflats. These habitats support a wide range of species, with significant Bridge or behind Da Vinci’s population of wading and wintering birds, including six of Northern Ireland’s priority Hotel, off the Culmore Road. species: redshank, herring gull, song thrush, mistle thrush, starling and bullfinch. Also, international over-wintering birds feast on the eel grass and insects on the mudflats. The woodlands and wildflower meadows provide a habitat for a range of priority species, including eight species of butterflies, for example, orange tip, tortoiseshell, peacock and painted ladies. Also, the willow trees provide a habitat for the lunar hornet moth, which mimics the behaviour of This riverside green space is managed by a wasp. The range of moths provide a Derry City Council for biodiversity and valuable source of food for the bats recreation, with a pedestrian and cycle that use the site for feeding. Two bat network. species have been recorded utilizing It was launched as Derry City Council’s first the site, Pipistrelle and Daubenton bats. Local Nature Reserve in June 2009, for its biodiversity, access, community involvement During your visit you may catch sight of a and educational value. -

Enhancing Nationally Determined Contributions Through Protected Areas Table of Contents

ENHANCING NATIONALLY DETERMINED CONTRIBUTIONS THROUGH PROTECTED AREAS TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 BACKGROUND 5 METHODOLOGY 7 RESULTS 13 1. EXPLICIT MENTION OF PROTECTED AREAS 13 2. ESTABLISHING NEW OR EXPANDING EXISTING PROTECTED AREAS 14 3. UTILIZING PROTECTED AREAS TO HELP PEOPLE ADAPT TO CLIMATE CHANGE (ECOSYSTEM-BASED ADAPTATION) 15 4. MITIGATION BENEFITS FROM CARBON SEQUESTRATION AND AUTHORS AVOIDED EMISSIONS 17 Abigail Hehmeyer, Jacqueline Vogel, Shaun Martin, Ryan Bartlett 5. MANAGING PROTECTED AREAS FOR CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS 18 DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 20 WWF CONCLUSION 27 GLOSSARY 28 For more than 50 years, WWF has been protecting the future of nature. One APPENDICES 31 of the world’s leading conservation organizations, WWF works in nearly 100 countries and is supported by more than 1.1 million members in the United APPENDIX 1: RESULTS BY COUNTRY 31 States and 5 million supporters globally. WWF’s unique way of working APPENDIX 2: COUNTRIES RANKED BY CREDITS EARNED FOR THE combines global reach with a foundation in science, involves action at every level 5 CRITERIA EXAMINED 39 from local to global, and ensures the delivery of innovative solutions that meet the needs of both people and nature. Visit worldwildlife.org to learn more. APPENDIX 3: COUNTRIES REFERENCED IN THIS REPORT, LISTED BY REGION 41 REFERENCES 43 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this analysis, conducted by WWF US, was made possible by the Support Project for the Implementation of the Paris Agreement (SPA), which is implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) under its International Climate Initiative (IKI). -

Vietnam: Van Long Nature Reserve

Van Long Nature Reserve Vietnam Van Long – local fishers cast nets in the limestone fringed community wetland By Dao Nguyen May 2008 Executive summary Van Long Nature Reserve is situated in Gia Vien district along the Northeastern border of Ninh Binh Province. Van Long straddles seven communes (local Government administrative units) and is in the heartland of the populated centre of north-eastern Vietnam, 85km south of the capitol, Hanoi. All the 45,000 or so people who live in these seven communes in the buffer zone of Van Long are of the Kinh ethnic Vietnamese majority. Van Long itself covers some 3,000 hectares and comprises two major geographic features. Firstly, Van Long is a large wetland and freshwater system. Secondly, the canals, lakes and streams wend through an island-like landscape of karst limestone mountains that harbour the only viable population of the Delacour Langur - one of the world’s most critically endangered species of primate (with less than 200 individuals remaining, globally). Without the protection afforded Van Long by the local community, and now by the Government and local authorities, it is highly probable that the Delacour langur would be the first primate extinction of the 21st Century. The name Van Long dates back centuries, and the community has evidenced a robust capacity to harness the natural resources of Van Long through decades of intense conflict and change, without diminishing their resource base. The cultural significance of the wetland-karst landscape is a vital part of local folklore and sense of place. With the outside discovery of the population of Delacour’s Langur in 1993, external attention to Van Long began to increase. -

Insert Proposal Title

STATUS QUO TECHNICAL NOTE ENVIRONMENT South Eastern District Local Area Plan 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 This Technical Note represents part of the Phase Two Deliverable for the South Eastern District Local Area Plan. 1.1 DETAILS OF THE STUDY AREA ....................................................................................................................... 1 Contract No. SCM 66 of 11/12 2 ENVIRONMENTAL STATUS QUO ............................................................................................................... 1 Prepared for: 2.1 AIR QUALITY AND CLIMATE ......................................................................................................................... 1 Msunduzi Municipality 2.2 GEOLOGY, SOILS AND TOPOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 Topography ................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2.2 Geology ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2.3 Soils, Land Cover and Land Capability ...................................................................................................... 5 2.3 BIODIVERSITY ............................................................................................................................................. -

What Is Inclusive Conservation and Why Is It Important to Biodiversity Conservation and Protected Area Management?

Fact Sheet What is inclusive conservation and why is it important to biodiversity conservation and protected area management? October 2019 ‘Inclusive Conservation’ is a trans-disciplinary approach to balancing stakeholder visions, and promoting shared agreements for the future management of protected areas through the development and application of multiple tools and processes. - 2 - Protecting our natural areas Global context Protected areas are clearly defined geographical spaces, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated Figure 1: Growth in ecosystem services and cultural values.1 Protected areas are critical for protected area coverage conserving local to regional biodiversity, particularly the characteristic on land and in the ocean (Exclusive Economic Zones of threatened species, habitats and ecosystems.2,3 (EEZ) and Areas Beyond At a global level, Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) National Jurisdiction (ABNJ)) between 1990 agreed in 2010 to a target of protecting at least 17% of terrestrial and and 2018 and projected inland water areas, and 10% of coastal and marine areas (Aichi Target growth to 2020 according 11), by 2020. Currently, protected areas cover almost 15% of land and to commitments from countries and territories.5 inland waters and 8% of the world’s oceans.4 (Figure 1). Area (Million km2) 40 2 30 3 20 10 1 0 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 1 ABNJ 2 EEZ 3 Land - 3 - Despite this expansion, protected areas only partly cover important sites for biodiversity, and there are issues associated with their ecological representativeness and equitable management6. -

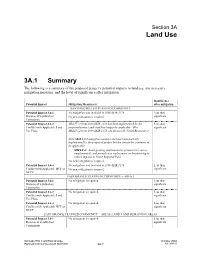

Section 3A Land Use

Section 3A Land Use 3A.1 Summary The following is a summary of the proposed project’s potential impacts to land use, any necessary mitigation measures, and the level of significance after mitigation. Significance Potential Impact Mitigation Measure(s) after mitigation SANTIAGO HILLS II PLANNED COMMUNITY Potential Impact 3A-1. No mitigation was included in 2000 SEIR 1278. Less than Division of Established No new mitigation is required. significant Community Potential Impact 3A-2. MM-LU-1 from 2000 SEIR 1278 has been implemented by the Less than Conflict with Applicable Land proposed project and would no longer be applicable. (For significant Use Plans MM-LU-2 from 2000 SEIR 1278, see Section 3I, Visual Resources.) 2000 SEIR 1278 mitigation measure that has been partially implemented by the proposed project but the remainder continues to be applicable: MM LU-3. Limit grading (implemented), prepare tree survey (implemented), and provide tree replacement and monitoring to reduce impacts to Irvine Regional Park. No new mitigation is required. Potential Impact 3A-3. No mitigation was included in 2000 SEIR 1278. Less than Conflict with Applicable HCP or No new mitigation is required. significant NCCP EAST ORANGE PLANNED COMMUNITY – AREA 1 Potential Impact 3A-1. No mitigation is required. Less than Division of Established significant Community Potential Impact 3A-2. No mitigation is required. Less than Conflict with Applicable Land significant Use Plans Potential Impact 3A-3. No mitigation is required. Less than Conflict with Applicable HCP or significant NCCP EAST ORANGE PLANNED COMMUNITY – AREAS 2 AND 3 AND REMAINING AREAS Potential Impact 3A-1. -

E-367 Georgia

E-367 GEORGIA PROTECTED AREAS DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Environmental Assessment, Environmental Management Plan 1. Introduction. The Government of Georgia (GoG) has requested that the International Public Disclosure Authorized Development Association (the Bank) provide support through the Global Environment Facility (GEF) for a Protected Areas Development Project. This Project will help the GoG to improve the conservation and sustainable use of Georgian biodiversity. 2. The project will: (i) establish three protected areas in eastern Georgia; (ii) facilitate the creation of a national network of protected areas; (iii) integrate biodiversity conservation into forestry, range management, and agriculture; (iv) strengthen institutions responsible for biodiversity conservation programs; (iv) improve public awareness of the values and importance of Georgian biodiversity; and (v) promote regional / international cooperation for conservation of biodiversity in the Caucasus region. 3. The Implementing Agency for the Project is the Georgia Department of Protected Areas. Financing for Project preparation commenced in March, 1999. Significant analysis and Public Disclosure Authorized proposals for Project financing were developed in partnership with the Department of Protected Areas administrations of three proposed project sites (Vashlovani, Lagodekhi and Tusheti); NGOs; the scientific community, international experts, and Georgian governmental institutions (Ministry of Environment). During project preparation, an environmental review identified the potential impacts of project activities and elaborated environmental review and management plan to be undertaken during project implementation. 4. The results of the environmental review and the recommended environmental management plan were the subject of public consultations held for each protected area site between June 12 and 14,2000. Comments were recorded in minutes (see Annex 5, Summary of Consultations; full minutes are available in Georgian from the Project Implementation Unit). -

Summary on Marine and Coastal Protected Areas in NOWPAP Region

Summary on Marine and Coastal Protected Areas in NOWPAP Region (NOWPAP DINRAC, March 2010) 1. Overview This summary is based on the Database on Coastal and Marine Nature Reserves in the Northwest Pacific Region (NowpapNatureReserve, http://dinrac.nowpap.org/NowpapNatureReserve.php) which is developed and maintained by NOWPAP DINRAC. The data was collected and provided by the National Focal Points of DINRAC started from 2006 and updated periodically. The WDPA (World database of protected areas, http://www.wdpa-marine.org), and the Ramsar Sites Database (http://ramsar.wetlands.org) were also taken as reference. The summary intends to give an overview and understanding on current situation of marine and coastal protected areas (MPAs) in NOWPAP region. The MPAs - marine and coastal protected areas comprise the nature reserves, national parks, wetland protected areas (Ramsar Sites) in NOWPAP Region. The sea area mainly covers the Yellow Sea and Eastern Area of NOWPAP region. Based on the existing data, there are total 87 MPAs in NOWPAP region covers an area of 4,090,046ha (Table 1 to Table 3). The earliest MPA was established in October 1916 and the latest was in August 2007 (Table 4). The smallest area is 10ha in Japan and largest area is 909,000ha in China (Table 5). Statistics tables and figures below are conducted on number, area, protected level, protected type and protected objectives (species) for MPAs in NOWPAP (Table 6 and Fig.1 to Fig.5). The list (List 1) and the location of the MPAs (Map 1) are listed individually. 2. Statistics Table 1. Number of MPAs in NOWPAP Region by Country Level Protected Type Country Total Wild Municipal/ Natural Nature Number National Provincial animal and County ecosystem heritage plant China 20 9 5 6 15 17 17 Japan 31 17 14 0 31 31 20 Korea 22 22 0 0 22 20 13 Russia 14 7 7 0 14 14 7 Region 87 55 26 6 82 82 57 1 Table 2. -

Policy Highlights Marine Protected Areas Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes

Marine Protected Areas Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes Policy HIGHLIGHTS Marine Protected Areas Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes Progress in expanding the coverage of marine protected areas is underway. With a push from the Sustainable Development Goals their global coverage is expected to increase even further. But their effectiveness is uneven. It is one thing to draw a line on a map – it is another to effectively design, site, monitor and enforce them. We are starting to understand what works and what doesn’t. Adaptive management and improvements over time will be essential if marine conservation and sustainable use objectives are to be met. Simon Upton – OECD Environment Director POLICY HI G HLI G H T Pressures on marine ecosystems from human activities are already severe and the often S competing demands for marine space and resources are projected to rise. Costs of poor ocean management practices include environmental and social costs that are often not factored into decision-making processes. This undermines the resilience of the ecosystems upon which we depend, for food, for income, but also other less visible life-support functions such as coastal protection, habitat provisioning and carbon sequestration. Marine protected areas are one of the policy instruments available to help ensure the conservation and sustainable use of our vast yet vulnerable ecosystems. While progress is being made towards increasing the global coverage of marine protected areas, significantly greater efforts are needed to ensure these are also being located in areas that are under threat and can therefore yield greatest environmental benefits, and that they are effectively managed. -

Understanding and Assessing Equity in Protected Area Conservation a Matter of Governance, Rights, Social Impacts and Human Wellbeing

Understanding and assessing equity in protected area conservation A matter of governance, rights, social impacts and human wellbeing Phil Franks, Francesca Booker and Dilys Roe Issue Paper Biodiversity; Governance Keywords: February 2018 Equity, conservation, protected areas, Social Assessment of Protected Areas (SAPA), wellbeing About the author Phil Franks is a senior researcher in the biodiversity team at IIED. Francesca Booker is a researcher in the biodiversity team at IIED. Dilys Roe is a principal researcher in the biodiversity team at IIED. Corresponding author: Phil Franks, [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Natural Resources Group The aim of the Natural Resources Group is to build partnerships, capacity and wise decision-making for fair and sustainable use of natural resources. Our priority in pursuing this purpose is on local control and management of natural resources and other ecosystems. Acknowledgments This paper builds on the work of a large group of people who have worked over the last three years on the development of the equity framework for protected area management and governance. Annex 1 contains the latest version of this framework at the time of publication, which reflects discussions at a workshop in April 2017 and a recent round of comments. We would like to acknowledge, in particular, the contribution of Kate Schreckenberg and Adrian Martin (co-authors of our earlier publications), staff of the Forest Peoples’ Programme for their detailed comments on the latest version of the framework, and Noelia Zafro-Calvo for being the first person to put the framework to good use. Published by IIED, February 2018 Franks, P et al.