Coping After a Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STAB WOUNDS PENETRATING the LEFT ATRIUM by MILROY PAUL from the General Hospital, Colombo, Ceylon

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.16.2.190 on 1 June 1961. Downloaded from Thorax (1961), 16, 190. STAB WOUNDS PENETRATING THE LEFT ATRIUM BY MILROY PAUL From the General Hospital, Colombo, Ceylon (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION NOVEMBER 15, 1960) A stab wound penetrating the left atrium followed by 4 pints of dextran throughout the night. (excluding the left auricle) would have to penetrate At 7 a.m. the next day he was still alive, breathing through other chambers of the heart or through quietly, with a pulse of 122 of good volume, blood the great arteries at their origin from the heart to pressure 100/70 mm. Hg, and warm extremities. Although there was still no blood in the bank, an reach the left atrium from the front of the chest. operation was decided on and begun at 8 a.m. Bv Such wounds would be fatal, the patient dying this time the pulse had again become small, although from profuse haemorrhage within a few minutes. the extremities were warm. The left chest was opened A stab wound through the back of the chest could through an intercostal incision in the eighth intercostal reach the left atrium in the narrow sulcus between space. The left pleural cavity contained fluid blood the root of the left lung in front and the oeso- and clots. In the outer surface of the lung under- phagus and descending thoracic aorta behind, but lying the stab wound of the chest wall there was a placing a wound at this site without at the same stab wound of the lung. -

Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Penetrating Chest Trauma

WTA 2014 ALGORITHM Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Penetrating chest trauma Riyad Karmy-Jones, MD, Nicholas Namias, MD, Raul Coimbra, MD, Ernest E. Moore, MD, 09/30/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== by http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma from Downloaded Martin Schreiber, MD, Robert McIntyre, Jr., MD, Martin Croce, MD, David H. Livingston, MD, Jason L. Sperry, MD, Ajai K. Malhotra, MD, and Walter L. Biffl, MD, Portland, Oregon Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma his is a recommended algorithm of the Western Trauma Historical Perspective TAssociation for the acute management of penetrating chest The precise incidence of penetrating chest injury, varies injury. Because of the paucity of recent prospective randomized depending on the urban environment and the nature of the trials on the evaluation and management of penetrating chest review. Overall, penetrating chest injuries account for 1% to injury, the current algorithms and recommendations are based 13% of trauma admissions, and acute exploration is required in by on available published cohort, observational and retrospective BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== 5% to 15% of cases; exploration is required in 15% to 30% of studies, and the expert opinion of the Western Trauma Asso- patients who are unstable or in whom active hemorrhage is ciation members. The two algorithms should be reviewed in the suspected. Among patients managed by tube thoracostomy following sequence: Figure 1 for the management and damage- alone, complications including retained hemothorax, empy- control strategies in the unstable patient and Figure 2 for the ema, persistent air leak, and/or occult diaphragmatic injuries management and definitive repair strategies in the stable patient. -

Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Emergency Department Nurses

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview Research and Major Papers 5-2018 Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Emergency Department Nurses Melissa Machado Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd Part of the Occupational and Environmental Health Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Machado, Melissa, "Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Emergency Department Nurses" (2018). Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview. 267. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd/267 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SECONDARY TRAUMATIC STRESS AMONG EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT NURSES by Melissa Machado A Major Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Nursing in The School of Nursing Rhode Island College 2018 Abstract Individuals employed in healthcare services are exposed daily to a variety of health and safety hazards which include psychosocial risks, such as those associated with work-related stress. Nursing is the largest group of health professionals in the healthcare system. Work-related -

Isolated Pneumopericardium After Penetrating Chest Injury

CASE REPORT East J Med 24(4): 558-559, 2019 DOI: 10.5505/ejm.2019.25582 Isolated Pneumopericardium After Penetrating Chest Injury Hasan Ekim1*, Meral Ekim2 1Bozok University Faculty of Medicine Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Yozgat 2 Bozok University Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Emergency Aid and Disaster Management, Yozgat ABSTRACT Pneumopericardium is defined as the presence of air or gas in the pericardial sac. Its course is stable unless tension pneumopericardium develops. However, even patients with asymptomatic pneumopericardium should be carefully monitored due to risk of tension pneumopericardium. We presented a 24-year-old male victim with stab wound complicated with isolated pneumopericardium. Pneumopericardium was accidentally encountered by plain chest radiograph. It was spontaneously resolved without pericardiocentesis or pericardial window. Key Words: Pneumopericardium, Stab Wound, Isolated Introduction Discussion Pneumopericardium is defined as the presence of air Pneumopericardium is a rare complication of blunt or or gas in the pericardial sac (1). It is commonly seen penetrating thoracic trauma and may also occur in neonates on mechanical ventilation and in victims iatrogenically (3). In addition, pericardial infections sustaining blunt thoracic trauma (1). However, may also lead to pneumopericardium (4). Lee et al (5) iatrogenic lesions such as barotrauma, endoscopic and reported that the swinging movement of the drainage surgical interventions may also lead to bottle may allow air in the bottom of the bottle to pneumopericardium. (2). A pneumopericardium due enter the chest tube and then into the pericardial to penetrating thoracic trauma is also rare (1). We space leading to pneumopericardium. Therefore, care presented an interesting case of stab wound should be taken when transporting patients complicated with isolated pneumopericardium. -

Practice Management Guidelines for Selective Nonoperative Management of Penetrating Abdominal Trauma

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT UPDATE Practice Management Guidelines for Selective Nonoperative Management of Penetrating Abdominal Trauma John J. Como, MD, Faran Bokhari, MD, William C. Chiu, MD, Therese M. Duane, MD, Michele R. Holevar, MD, Margaret A. Tandoh, MD, Rao R. Ivatury, MD, and Thomas M. Scalea, MD and minimal to no abdominal tenderness. Diagnostic laparoscopy may be Background: Although there is no debate that patients with peritonitis or considered as a tool to evaluate diaphragmatic lacerations and peritoneal hemodynamic instability should undergo urgent laparotomy after pene- penetration in an effort to avoid unnecessary laparotomy. trating injury to the abdomen, it is also clear that certain stable patients Key Words: Practice management guidelines, Penetrating abdominal without peritonitis may be managed without operation. The practice of trauma, Selective nonoperative management, Nontherapeutic laparoctomy, deciding which patients may not need surgery after penetrating abdom- Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. inal wounds has been termed selective management. This practice has been readily accepted during the past few decades with regard to (J Trauma. 2010;68: 721–733) abdominal stab wounds; however, controversy persists regarding gunshot wounds. Because of this, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guidelines Committee set out to develop guidelines to analyze which patients may be managed safely without STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM laparotomy after penetrating abdominal trauma. A secondary goal of this -

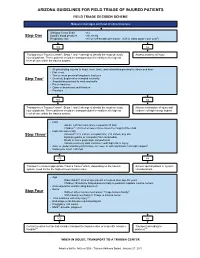

Guidlines for Field Triage of Injured Pts Final .Pdf

ARIZONA GUIDELINES FOR FIELD TRIAGE OF INJURED PATIENTS FIELD TRIAGE DECISION SCHEME Measure vital signs and level of consciousness Glasgow Coma Scale <14 Step One Systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg Respiratory rate <10 or >29 breaths per minute (<20 in infant aged < one year1) YES NO Transport to a Trauma Center2. Steps 1 and 2 attempt to identify the most seriously Assess anatomy of injury. injured patients. These patients should be transported preferentially to the highest level of care within the trauma system. • All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and extremities proximal to elbow and knee • Flail chest • Two or more proximal long-bone fractures 3 Step Two • Crushed, degloved or mangled extremity • Amputation proximal to wrist and ankle • Pelvic fractures • Open or depressed skull fracture • Paralysis YES NO Transport to a Trauma Center2. Steps 1 and 2 attempt to identify the most seriously Assess mechanism of injury and injured patients. These patients should be transported preferentially to the highest evidence of high-energy impact. level of care within the trauma system. • Falls ◦ Adults: >20 feet (one story is equal to 10 feet) ◦ Children4: >10 feet or two or three times the height of the child • High-risk auto crash 3 5 Step Three ◦ Intrusion : >12 inches, occupant site; >18 inches, any site ◦ Ejection (partial or complete) from automobile ◦ Death in same passenger compartment ◦ Vehicle telemetry data consistent with high risk of injury • Auto vs. pedestrian/bicyclist thrown, run over, or with significant (>20 mph) impact6 • Motorcycle crash >20 mph YES NO Transport to closest appropriate Trauma Center7 which, depending on the trauma Assess special patient or system system, need not be the highest level trauma center. -

Assessment and Management of the Injured Abdomen

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.62.725.155 on 1 March 1986. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (1986) 62, 155-158 Review Article Assessment and management ofthe injured abdomen T.G. Parks Department ofSurgery, The Queen's University ofBelfast, Belfast, UK. In many countries trauma remains the major cause of incipient paralytic ileus, significant injury should be death in patients under 40 years of age. Severe blunt strongly suspected. abdominal trauma occurs most often as a result of In patients with multiple injuries, abdominal road traffic accidents but it is not uncommon in trauma may represent a major challenge in diagnosis industrial injuries, civil violence or participation in and treatment. In other instances there may be no sport. The death toll in the European Economic significant injury to the abdomen but this may be Community from road traffic accidents alone totals difficult to substantiate with certainty initially. 50,000 per year. Furthermore, for every fatality there Altered level of consciousness due to head injury, are 20 cases ofserious injury. With improved transport presence of concurrent chest or skeletal injuries, services and vigorous resuscitative measures more of hypovolaemia and shock may add to the problems of these critically ill patients are surviving long enough to diagnosis in cases of abdominal trauma. reach the operating theatre for emergency surgery. A diagrammatic representation of a suggested The wearing of automobile seat belts has not only scheme for the clinical management of patients with reduced the mortality but also the frequency and penetrating and non-penetrating injuries is given in copyright. -

Associated Injuries and Complications of Stab Wounds of the Spinal Cord

ASSOCIATED INJURIES AND COMPLICATIONS OF STAB WOUNDS OF THE SPINAL CORD By ROBERT LIPSCHITZ, F.R.C.S.E. Principal Neurosurgeon, Department of Neurosurgery, Baragwanath Hospital, and the University of the Witwatersrand THIS review follows on an earlier series (Lipschitz and Block, 1962). At that stage 130 cases of stab wounds of the spinal cord were discussed and these occurred over a period of 4! years, viz. 1955-1959. In the following eight years, because of improved socio-economic conditions amongst the Africans living in and around Johannesburg our figures have decreased and only a further 122 cases have been collected, making a total of 252 all in all. In this group there were no less than 86 associated injuries. These stab wounds of the spine have on occasion been inflicted with the deliberate intention of making the patient paraplegic but more recently this means of 'getting even' with a fellow-gangster has been replaced by more sophisticated methods. The majority of our stab wounds of the spine occur as the result of generalised stabbing. Our hospital, which in the pre-1960's used to admit over 5,000 cases of generalised stabbing a year, now admits less than 2,500 stab wound cases annually. As most of these stab wounds are haphazardly inflicted, the chances are that a certain number will penetrate into the spinal column and destroy or damage the cord. The weapon, as stated previously, can be any sharp instrument which is long enough and strong enough to be effective. Knives of every shape and description were by far the commonest though we have also encountered such weapons as sharpened screw-drivers and bicycle spokes. -

Intracranial Stab Injuries: Case Report and Case Study

Forensic Science International 129 (2002) 122–127 Intracranial stab injuries: case report and case study Martin Bauer*, Dieter Patzelt Institute of Legal Medicine, University of Wuerzburg, Versbacher Strasse 3, 97078 Wuerzburg, Germany Received 13 February 2002; received in revised form 27 June 2002; accepted 9 July 2002 Abstract Non-missile penetrating brain injuries are rare events in western countries. We report a case with lethal stab injury of the brain and identification of the weapon used in the assault by digital superimposition on CT scans taken at admission of the victim to a hospital. Furthermore, all cases with knife stab wounds of the skull between 1971 and 2000 were analyzed and compared with literature reports. Results of this study show that there is no region preference despite of differences in bone thickness, that stab wounds of the brain are almost invariably associated with multiple stab wounds to the trunk and that the wound tract may correspond to the dimensions of the blade allowing the identification of the weapon by digital image analysis. # 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Stab wound; Brain; Superimposition; Computed tomography; Slot fracture 1. Introduction 2. Case report Stab wounds of the brain are relatively uncommon in A 60-year-old man was involved in an altercation which western countries because the adult calvarium usually pro- resulted in the patient sustaining multiple wounds to the vides an effective barrier [1]. However, there are areas of thin chest and head. At arrival to the trauma center the patient bone such as the orbitae or the temporal region where knives was comatose and responsive only to deep pain. -

Neurological Findings in Pediatric Penetrating Head Injury at a University Teaching Hospital in Durban, South Africa: a 23-Year Retrospective Study

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg Pediatr 18:550–557, 2016 Neurological findings in pediatric penetrating head injury at a university teaching hospital in Durban, South Africa: a 23-year retrospective study Kadhaya David Muballe, MD,1 Timothy Hardcastle, MMed, PhD,2 and Erastus Kiratu, MBChB1 Department of 1Neurosurgery and 2Trauma Surgery, Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital and University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa OBJECTIVES Penetrating traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) can be divided into gunshot wounds or stab wounds based on the mechanisms of injury. Pediatric penetrating TBIs are of major concern as many parental and social factors may be involved in the causation. The authors describe the penetrating cranial injuries in pediatric patient subgroups at risk and presenting to the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, by assessment of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score and review of the common neurological manifestations including cranial nerve abnormalities. METHODS The authors performed a retrospective chart review of children who presented with penetrating TBIs be- tween 1985 and 2007 at a university teaching hospital. Descriptive statistical analysis with univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the variables. RESULTS Out of 223 children aged 16 years and younger with penetrating TBIs seen during the study period, stab wounds were causal in 127 (57%) of the patients, while gunshot injuries were causal in 96 (43%). Eighty-four percent of the patients were male. Apart from abnormal GCS scores, other neurological abnormalities were noted in 109 (48.9%) of the patients, the most common being cranial nerve deficits (22.4%) and hemiparesis. -

High Rates of Acute Stress Disorder Impact Quality-Of-Life Outcomes in Injured Adolescents: Mechanism and Gender Predict Acute Stress Disorder Risk Troy L

The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care High Rates of Acute Stress Disorder Impact Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Injured Adolescents: Mechanism and Gender Predict Acute Stress Disorder Risk Troy L. Holbrook, PhD, David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, Raul Coimbra, MD, FACS, Bruce Potenza, MD, FACS, Michael Sise, MD, FACS, and John P. Anderson, PhD -p < 0.01; 6-month, ASD ,0.710 ؍ Background: Injury is the leading were enrolled in the study. The admis- score -vs. ASD 0.704 ؍ cause of death and functional disability sion criteria for patients were as follows: positive QWB score ;p < 0.001 ,0.742 ؍ in adolescent children. Little is known (1) age 12 to 19 years and (2) injury negative QWB score ؍ about quality of life and psychological diagnoses excluding severe traumatic 12-month: ASD-positive QWB score ؍ outcomes after trauma in adolescents. brain injury (TBI) or spinal cord injury. 0.718 vs. ASD-negative QWB score The Trauma Recovery Project in Ado- QoL after trauma was measured using 0.757, p < 0.01; 24-month, ASD-positive vs. ASD-negative 0.725 ؍ lescents is a prospective epidemiologic the Quality of Well-being (QWB) scale, QWB score p < 0.01. Female sex ,0.769 ؍ study designed to examine multiple out- a sensitive and well-validated functional QWB score op- and violent mechanism predicted ASD ؍ death to 1.000 ؍ comes after major trauma in adolescents index (range, 0 aged 12 to 19 years, including quality of timum functioning). ASD (before dis- risk (47% female vs. 36% male; odds ra- life (QoL) and psychological sequelae charge) was diagnosed with the Impact tio, 1.6; p < 0.05; violence 54% vs. -

Case Reviews EMS Coordinator Financial Disclosure Case 1-EMS Course for the Advanced ◼ Called to an MVA

David Sanko, BA, NR-Paramedic Trauma Case Reviews EMS Coordinator Financial Disclosure Case 1-EMS Course for the Advanced ◼ Called to an MVA ◼ No relevant financial relationships with ◼ 39 y/o male restrained driver of car traveling roughly Provider-7.0 any commercial interests exists. 70 mph on E-470 ◼ Impacted a guard rail which flipped the car over ◼ We will not be discussing any “off-label” uses of products or medications ◼ Part of the wooden guardrail penetrated the engine compartment, through the firewall and into ◼ Be sure to always default to your local the passenger compartment where the patient medical direction and protocols in place. legs were impacted. ◼ + A/B deployment, + SW broken with the driver’s David Sanko, BA, NRP seat actually displaced by the impact. EMS Coordinator of Education & Training Case 1- EMS Course Case 1-EMS Course Case 1 –EMS Course ◼ EMS VS : Reported unable to obtain a blood ◼ EMS Treatment: pressure, HR=70, RR=20, EKG= STACH ◼ Tourniquet application ◼ GEN: No LOC, AAOx3, C/P right leg pain, Skin ◼ Extricated to LSB pale, cool, dry, + EtOH on breath noted. Morbidly ◼ IV access x 2 with IVF x 400 ml infused obese at 5’10” and 333 lbs (151 kg) ◼ O2 via NC ◼ HEENT: 5 cm laceration above the right eye, ◼ EMS reported unable to utilized SNC due to body habitus so they manually stabilized the cervical spine ◼ EXT: Right leg is mangled and almost completely fully amputated below the knee with both tibia throughout the transport with towels and hands. and fibula visible just above the ankle, the foot is ◼ ED VS= 110/50, 67, 22, 94%, 36.6 mangle and actually folded up under the leg itself, ◼ PMHx= congenital single left kidney, left ankle problems the leg had significant oozing bleeding with no with left talocalcaneal fusion, Leukemia in remission with overt arterial spurting noted, EBL=500 ml on residual UE neuropathy from chemotherapy scene according to EMS.