Nurturing Spirituality the Case of Adventist Education in Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Seventh-Day Adventist Colleges and Universities

DIRECTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ADVENTIST ACCREDITING ASSOCIATION Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, Maryland 20904 USA 2018-2019 CONTENTS Preface 5 Board of Directors 6 Adventist Colleges and Universities Listed by Country 7 Adventist Education World Statistics 9 Adriatic Union College 10 AdventHealth University 11 Adventist College of Nursing and Health Sciences 13 Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies 14 Adventist University Cosendai 16 Adventist University Institute of Venezuela 17 Adventist University of Africa 18 Adventist University of Central Africa 20 Adventist University of Congo 22 Adventist University of France 23 Adventist University of Goma 25 Adventist University of Haiti 27 Adventist University of Lukanga 29 Adventist University of the Philippines 31 Adventist University of West Africa 34 Adventist University Zurcher 36 Adventus University Cernica 38 Amazonia Adventist College 40 Andrews University 41 Angola Adventist Universitya 45 Antillean Adventist University 46 Asia-Pacific International University 48 Avondale University College 50 Babcock University 52 Bahia Adventist College 55 Bangladesh Adventist Seminary and College 56 Belgrade Theological Seminary 58 Bogenhofen Seminary 59 Bolivia Adventist University 61 Brazil Adventist University (Campus 1, 2 and 3) 63 Bugema University 66 Burman University 68 Central American Adventist University 70 Central Philippine Adventist College 73 Chile -

World Report 2019 Adventist Education Around the World

World Report 2019 Adventist Education Around the World General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Department of Education December 31, 2019 Table of Contents World Reports ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Basic School Type Definitions ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 World Summary of Schools, Teachers, and Students ............................................................................................................................................. 8 World Summary of School Statistics....................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Division Reports ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 10 East-Central Africa Division (ECD) ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Pirates in the Library

Librarian Life Rules Human Library Little Free Library p 4 p 8 p 10 CTION ASDALVolume 37 | Number 1 | Fall 2017 Association A of Seventh-Day Adventist Librarians Pirates in the Library p 12 ASDAL ACTION | FALL 2016 1 ASDAL Action Volume 37, No. 1 | Fall 2017 ISSN 1523-8997 Editor Jessica Spears contents About ASDAL ASDAL is an organization for individuals interested in Seventh-day Adventist 34 librarianship. The Association was formed to enhance communication between Seventh- day Adventist librarians, and to promote librarianship and library services to Seventh- day Adventist institutions. The association holds an Annual Conference, publishes ASDAL Action, awards the D. Glenn Hilts Scholarship, and is a sponsor of the Seventh-day Adventist Periodical Index. The Adventist Library Information Cooperative (ALICE), is a service provided by the Association to provide Member Libraries with enhanced database access opportunities at reduced costs through collective efforts and resource sharing within FEATURES the Cooperative. Librarain Life Rules Little Free Library Letters to the Editor 4 10 We welcome your comments and questions. by Bruce McClay by Deyse Bravo-Rivera Please submit letters to the editor to [email protected]. Human Library Pirates in the ASDAL Membership 8 12 Library Membership is open to those who support the by Michelle Down goals of the Association. Members receive a by Melissa Hortemiller one year subscription to ASDAL Action and discounted conference registration. Get Involved with ASDAL All members are invited to get -

Valley View University and Catholic University College of Ghana Gasu- Strengthening Higher Der.Indd 164 14/11/2018 23:28:28 8

SECTION IV Two Private Universities: Valley View University and Catholic University College of Ghana Gasu- Strengthening Higher der.indd 164 14/11/2018 23:28:28 8 Valley View University From Missionary College to a Chartered University The Valley View University (VVU) has the singular distinction of being the first chartered private university in Ghana. The institution has a vision of becoming ‘…a leading Centre of Excellence in Christian Education’ (VVU 2014). The University, therefore, seeks in its mission statement to emphasise ‘…academic, spiritual, vocational and technological excellence in a context that prepares lives for service of God and humanity’ (VVU 2014). The statements pertaining to the University’s vision and mission provide some insights into its ecclesiastical origins; even as efforts are being made to wed the theological with secular education. The origins of the Valley View University can be traced to the setting up of the Adventist Missionary College at Bekwai-Ashanti in 1979. The Adventist Missionary College was founded by the West African Union Mission of Seventh- day Adventists, with the intent of training clerics for the Seventh-day Adventists mission. The Missionary College was relocated to Adentan near Accra in 1983, where it was housed in a rented premise. The Adventist Missionary College was moved, yet again, from Adentan to its present site at Oyibi in 1989; and was renamed the Valley View College. With the liberalisation of the higher education system that allowed the operationalisation of private actors in the sector, the Valley View College, in 1995, became an affiliated institution to the Griggs University in Silver Springs, USA. -

Graduate Business Education in Adventist Colleges and Universities: History and Challenges Annetta M

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University School of Business Administration Faculty School of Business Administration Publications April 2012 Graduate Business Education in Adventist Colleges and Universities: History and Challenges Annetta M. Gibson Andrews University, [email protected] Robert Firth Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/sba-pubs Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Gibson, Annetta M. and Firth, Robert, "Graduate Business Education in Adventist Colleges and Universities: History and Challenges" (2012). School of Business Administration Faculty Publications. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/sba-pubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Business Administration at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Business Administration Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GraduaTe BuSIneSS eduCaTIon In advenTIST ColleGeS and unIverSITIeS: H ISTORYAND C HALLENGES raduate business educa- Single and Double Entry, Commercial ulty, especially academically trained tion is in high demand Calculations and the Philosophy of teachers with terminal degrees. At the everywhere, including the Morals of Business (1866) as one of the same time, a new business accrediting Seventh-day Adventist college textbooks. The Second Annual body, the AACSB (Association to Ad- Church. Since 1990, 34 Catalogue included bookkeeping as a vance Collegiate Schools of Business) GMaster’s programs in business have separate course.2 By 1879, the college developed standards for business cur- been started at various Adventist col- had a Commercial Department, which riculum, library holdings, faculty quali- leges and universities; 14 of these pro- continued when the school moved in fications, and faculty research. -

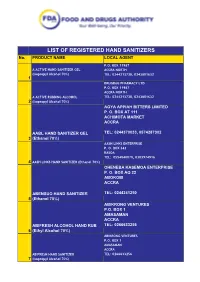

LIST of REGISTERED HAND SANITIZERS No

LIST OF REGISTERED HAND SANITIZERS No. PRODUCT NAME LOCAL AGENT P.O. BOX 11987 A ACTIVE HAND SANITIZER GEL ACCRA NORTH (Isopropyl Alcohol 70%) TEL: 0244213738, 0243801632 1 DRUGBAG PHARMACY LTD P.O. BOX 11987 ACCRA NORTH A ACTIVE RUBBING ALCOHOL TEL: 0244213738, 0243801632 2 (Isopropyl Alcohol 70%) AGYA APPIAH BITTERS LIMITED P. O. BOX AT 111 ACHIMOTA MARKET ACCRA AABL HAND SANITIZER GEL TEL: 0244370033, 0574287302 3 (Ethanol 70%) AASH LINKS ENTERPRISE P. O. BOX 343 KASOA TEL: 0554840078, 0303974916 4 AASH LINKS HAND SANITIZER (Ethanol 70%) OHENEBA KASEMOA ENTERPRISE P. O. BOX AQ 22 ABOKOBI ACCRA ABENSUO HAND SANITIZER TEL: 0244241250 5 (Ethanol 70%) ABIKRONG VENTURES P.O. BOX 1 AMASAMAN ACCRA ABIFRESH ALCOHOL HAND RUB TEL: 0266633256 6 (Ethyl Alcohol 70%) ABIKRONG VENTURES P.O. BOX 1 AMASAMAN ACCRA ABIFRESH HAND SANITIZER TEL: 0266633256 7 (Isopropyl Alcohol 70%) ABL HAND SANITIZER (Ethanol ACCRA BREWERY LIMITED 80%). P. O. BOX GP 351 ACCRA TEL: 0302688851-6 8 DANAP TOP CLASS ENTERPRISE P. O. BOX 439 KASOA ABLE HAND SANITIZER (Isopropyl TEL: 0545221406 9 Alcohol 70%) ABOKALA STAR VENTURES P. O. BOX 2690 SUNYANI BONO REGION TEL: 0244471321 10 ABOJOY HAND SANITIZER (Ethanol 70%) ABUMAAJ MEDIATION CENTRE P. O. BOX 1222 ADUM KUMASI TEL: 0244704488, 0556216882 11 ABUMAJ HAND SANITIZER (80% Ethanol) ABY-ELIZENT P. O. BOX 15577 ACCRA NORTH ABY HAND SANITIZER (Isopropyl Alcohol TEL: 0243442991, 0505762238 12 70%) DASK CHEMIST LTD P.O. BOX TN 1956 TESHIE NUNGUA A-CLEAN HAND SANITIZER GEL TEL: 0243041091, 0541024723 13 (Ethanol 70%) DASK CHEMIST LTD P.O. BOX TN 1956 TESHIE NUNGUA A-CLEAN HAND SANITIZER SPRAY TEL: 0243041091, 0541024723 14 (Ethanol 70%) ACQPONG ENTERPRISE P. -

Directory of Seventh-Day Adventist Colleges and Universities

DIRECTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ADVENTIST ACCREDITING ASSOCIATION Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities 12501 Old Columbia Pike, Silver Spring, Maryland 20904 USA 2018-2019 1 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Board of Directors ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Adventist Colleges and Universities Listed by Country ............................................................................................. 7 Adventist Education World Statistics ......................................................................................................................... 9 Adriatic Union College ............................................................................................................................... 10 AdventHealth University ........................................................................................................................... 11 Adventist College of Nursing and Health Sciences .................................................................................... 13 Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies ............................................................................... 14 Adventist University Cosendai .................................................................................................................. -

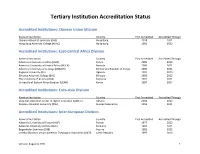

Tertiary Institution Accreditation Status

Tertiary Institution Accreditation Status Accredited Institutions: Chinese Union Mission Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Chinese Adventist Seminary (CAS) Hong Kong 2018 2021 Hong Kong Adventist College (HKAC) Hong Kong 1982 2022 Accredited Institutions: East-Central Africa Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Adventist University of Africa (AUA) Kenya 2005 2022 Adventist University of Central Africa (AUCA) Rwanda 2006 2021 Adventist University of Lukanga (UNILUK) Democratic Republic of Congo 2005 2021 Bugema University (BU) Uganda 1992 2023 Ethiopia Adventist College (EAC) Ethiopia 1993 2022 The University of Arusha (UOA) Tanzania 1992 2021 University of Eastern Africa Baraton (UEAB) Kenya 1987 2024 Accredited Institutions: Euro-Asia Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Ukrainian Adventist Center of Higher Education (UACHE) Ukraine 2004 2024 Zaoksky Adventist University (ZAU) Russian Federation 1994 2021 Accredited Institutions: Inter-European Division Name of Institution Country First Accredited Accredited Through Adventist University of France (AUF) France 1977 2022 Adventus University Cernica (AUC) Romania 1997 2021 Bogenhofen Seminary (SSB) Austria 1983 2022 Czecho-Slovakian Union Adventist Theological Institute (CSUATI) Czech Republic 1997 2024 Version: August 4, 2021 1 Listing of Seventh-day Adventist Colleges and Universities, continued Friedensau Adventist University (FAU) Germany 1984 2021 Italian Adventist University Villa -

Download the Post-Graduate Admission

Application for Graduate Studies Valley View University If you have previously attended /applied or presently attending Valley View University please enter your ID/Reference number here SECTION A PERSONAL DETAILS Surname [Mr. / Mrs. / Ms.]: Fix photograph here First Names: Please write your name and Other Names [if any]: proposed programme at the back of the photo Gender: Male Female Day Month Date of Birth Year Nationality: Age (as at your last B'day) Place of Birth: Passport No: Social Security No: National ID No: Marital Status: Permanent Address: Current Mailing Address [if different] Telephone: Mobile: Fax No: Email: Foreigners Only Yes If YES, attach a copy of your resident permit Are you permanently residing in Ghana? No SECTION B PROPOSED PROGRAMME OF STUDY What is your proposed programme? Master of Education in Curriculum and Instruction Master of Philosophy in Computer Science Master of Philosophy in Curriculum and Instruction Master of Education in Educational Administration and Leadership Master of Business Administration in Banking & Finance Master of Business Administration in Human Resource Management Master of Business Administration in Strategic Management Master of Business Administration in Accounting Post Graduate Diploma in Education Post Graduate Diploma in Pastoral Ministry [For research programme only ] Proposed field of Research, if admitted: Any previous work done in the general field of your intended research: Page 1 of 7 Campus: Accra (Oyibi) Kumasi(Kwadaso) Techiman(Site) Mode: Semester/Year of Application: Weekend (Sunday only) First [July/August] 20_______ Sandwich (Long Vac., Christmas & Easter) Second [January] 20_______ Elongated (Fridays & Sundays) Regular SECTION C EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION Please attach certified copies of transcripts and certificates. -

Post-Secondary Institutions

AAA Accreditation Status for Colleges and Universities The following list identifies by Division and Country all post-secondary institutions recognized and accredited by the Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities (AAA) along with the year each institution was first accredited and when current accreditation expires. Expiration is always on December 31 of the year identified, and during that same year an accreditation visit will be scheduled. The following definitions apply: ▪ Accredited: An institution with full accreditation. ▪ Mid-Level Training Institutions: Institutions that offer education which goes beyond secondary level education but is less than a bachelor’s degree. These include diploma teacher training, technical training in building and construction or other professional trades, and non-collegiate hospital-based schools of nursing (c.f. FE 30 15). ▪ In Candidacy: An institution in the process of application for full accreditation. Programs are still recommended for transfer to other accredited institutions. The maximum candidacy term is two years. ▪ In Pre-candidacy: An institution that has met basic criteria for operation and is working towards candidacy status. Programs are not yet recognized for transfer to other accredited institutions. The maximum pre-candidacy term is 5 years. ▪ On Probation: An institution that has held full accreditation but is not presently meeting accreditation expectations in certain critical areas. After a set period, accreditation will either be revoked -

SDA Mission in Southern Ghana Union Conference. Asia

http://dx.doi.org/10.21806/aamm.2016.14.06 Asia-Africa Journal of Mission and Ministry Vol. 14, pp. 91–109, Aug. 2016 SDA Mission in Southern Ghana Union Conference Oppong Kenneth Abiodun A. Adesegun Peter Obeng Manu ABSTRACT—Knowing the past will influence the present and mostly importantly, guide the future. Studying church history will help identify the failures of the past so as not to repeat them in the church today. It will also help identify the successes of the past so as to modify them to ensure the success of the church today. Church history is tantamount to the success of the present day church. The history and the mission of the Southern Ghana Union Conference in modern day Ghana calls for historical evaluation. This study seeks to trace the history of the Southern Ghana Union Conference and how it has carried on its mission since its establishment. The study is a historical evaluation of Southern Ghana Union Conference from 2013 to 2015. It was discovered that the leadership of the SGUC is mission conscious and Adventism is getting more rooted in the Southern part of Ghana. The historic growth of the Southern Ghana Union Conference has been enormous over the few years of its birth and a birth to a new Union Conference was foreseen by the researchers. It was noted that the Union has challenges, even, though it is speedily growing. Also, it was identified that appetizing church houses should be built to accommodate the fast growing membership of the Union. More so, the leadership of the Union should furnish some of Manuscript received June 11, 2016; revised Aug. -

Self Study, Andrews University’S Key Theme of “Seek Knowledge

Self-Study Report for the Comprehensive Visit Berrien Springs Michigan 49104 Prepared for The General Conference Accrediting Association of Seventh-day Adventist Schools, Colleges, and Universities December 5–7, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background ................................................................................................... 3 Institutional Profile ........................................................................................................ 5 Section A: Response to Major Recommendations from 2009 .........................................14 Section B: Standards Standard 1: Mission and Identity .............................................................................31 Standard 2: Spiritual Development, Witness and Service .........................................44 Standard 3: Governance, Organization and Administration ..................................... 60 Standard 4: Programs of Study ............................................................................... 70 Standard 5: Faculty and Staff ................................................................................. 95 Standard 6: Educational Context ...........................................................................102 Standard 7: Pastoral and Theological Education ....................................................131 Section C: Showcase on Health and Wellness ............................................................ 169 Introduction ...........................................................................................................171