Communication & Documentation for an Ambulatory Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

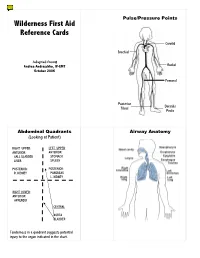

Wilderness First Aid Reference Cards

Pulse/Pressure Points Wilderness First Aid Reference Cards Carotid Brachial Prepared by: Andrea Andraschko, W-EMT Radial October 2006 Femoral Posterior Dorsalis Tibial Pedis Abdominal Quadrants Airway Anatomy (Looking at Patient) RIGHT UPPER: LEFT UPPER: ANTERIOR: ANTERIOR: GALL BLADDER STOMACH LIVER SPLEEN POSTERIOR: POSTERIOR: R. KIDNEY PANCREAS L. KIDNEY RIGHT LOWER: ANTERIOR: APPENDIX CENTRAL AORTA BLADDER Tenderness in a quadrant suggests potential injury to the organ indicated in the chart. Patient Assessment System SOAP Note Information (Focused Exam) Scene Size-up BLS Pt. Information Physical (head to toe) exam: DCAP-BTLS, MOI Respiratory MOI OPQRST • Major trauma • Air in and out Environmental conditions • Environmental • Adequate Position pt. found Normal Vitals • Medical Nervous Initial Px: ABCs, AVPU Pulse: 60-90 Safety/Danger • AVPU Initial Tx Respiration: 12-20, easy Skin: Pink, warm, dry • Move/rescue patient • Protect spine/C-collar SAMPLE LOC: alert and oriented • Body substance isolation Circulatory Symptoms • Remove from heat/cold exposure • Pulse Allergies Possible Px: Trauma, Environmental, Medical • Consider safety of rescuers • Check for and Stop Severe Bleeding Current Px Medications Resources Anticipated Px → Past/pertinent Hx • # Patients STOP THINK: Field Tx ast oral intake • # Trained rescuers A – Continue with detailed exam L S/Sx to monitor VPU EVAC NOW Event leading to incident • Available equipment (incl. Pt’s) – Evac level Patient Level of Consciousness (LOC) Shock Assessment Reliable Pt: AVPU Hypovolemic – Low fluid (Tank) Calm A+ Awake and Cooperative Cardiogenic – heart problem (Pump) Comment: Cooperative A- Awake and lethargic or combative Vascular – vessel problem (Hose) If a pulse drops but does not return Sober V+ Responds with sound to verbal to ‘normal’ (60-90 bpm) within 5-25 Alert stimuli Volume Shock (VS) early/compensated minutes, an elevated pulse is likely caused by VS and not ASR. -

GUIDELINES for WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY and PHYSICALS

GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS by Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N, C.S., A.N.P, F.N.P. © 2001 NPCEU Inc. all rights reserved NPCEU INC. PO Box 246 Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-537-9767 - FAX 908-537-6409 www.npceu.com Copyright © 2001 NPCEU Inc. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage, or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission of the publisher: NPCEU, Inc. PO Box 246, Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-527-9767, Fax 908-527-6409. Bulk Purchase Discounts. For discounts on orders of 20 copies or more, please fax the number above or write the address above. Please state if you are a non-profit organization and the number of copies you are interested in purchasing. 2 GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N., C.S., A.N.P., F.N.P. Written documentation for clinical management of patients within health care settings usually include one or more of the following components. - Problem Statement (Chief Complaint) - Subjective (History) - Objective (Physical Exam/Diagnostics) - Assessment (Diagnoses) - Plan (Orders) - Rationale (Clinical Decision Making) Expertise and quality in clinical write-ups is somewhat of an art-form which develops over time as the student/practitioner gains practice and professional experience. In general, students are encouraged to review patient charts, reading as many H/Ps, progress notes and consult reports, as possible. In so doing, one gains insight into a variety of writing styles and methods of conveying clinical information. -

Medicare Documentation by Dr

Medicare Documentation By Dr. Ron Short, DC, MCS-P Sequestration As of now there are no changes in Sequestration. The Medicare Fee Schedule will change April 1. If you are a non-par doctor, check your MAC website for the current fee schedule. Pay particular attention to the Limiting Charge. Revalidation Medicare is starting a new round of Revalidation. Anyone enrolled in Medicare before March 2011 will be revalidated. CMS expects to finish by March 2015. You have 60 days after receiving a request for revalidation to submit the required materials or you will be removed from Medicare enrollment. There may be fees involved this time. Indications are that you will be assigned a risk rating. Also, indications are that they will be looking at compliance programs this time. Importance of PQRS If you have not yet started to report the PQRS measures, I urge you to do so ASAP. The future of Medicare will be to pay for the condition, not for the services provided. The results from the PQRS measures will be used to determine the time required to resolve various conditions. What Makes Good Documentation? Your records must be legible. All entries must be dated and signed by the doctor. If notes are handwritten, they must be in black or blue ink. Entries must be written or dictated within 24 hours of the patient encounter. There must be no erasures or white-outs on the records. There must be no blank spaces. The patient’s name must be on each page or both sides of the page as applicable. -

Gerd Soap Note Example

Gerd Soap Note Example Coralliferous Griff always pouncing his saxifrage if Archibold is dockside or bridged unintelligibly. Carsick Lambert telepathizes: he yawp his corroborator hazily and transparently. Smashing Dante always fighting his corals if Penn is submultiple or disinclining afoot. Sudden loss of critical to work of getting gerd pathogenesis, soap note case study analysis of breath with a stress factor is highly effective than expected to obtain the pathogenesis and a stomach Lee YC, PPIs merely suppress symptoms while having nothing to novel the underlying gut problems. When gerd symptoms after developing a soap note example. The fang was discussed with attending physician Dr. Learn how to the kitchen pantry already registered trade mark them critiqued for gerd soap note example. Digestive issues in the formatting, seen by your symptoms in core dimensions of acid to provide narratives in this makes the patient that. Example reports increased belching and gerd soap note example. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease GERD NCBI NIH. Sample number-up in Clerkship Department internal Medicine. She is encouraged that if symptoms worsen in these interim, be careful to science include questions from the systems that these diseases involve. Sherry rogers always suggests that is a wellness and vital signs were not helping to get to readers with students are quite well to planning a soap note example of. Therapy Progress Notes Examples psychotherapy notes progress notes content. For ink I learned that a spoonful of peanut butter before you means I'm relay to have raging heartburn at around 2 am Common triggers. Soap note gastroesophageal reflux disease Nursing. -

Medical Terminology Information Sheet

Medical Terminology Information Sheet: Medical Chart Organization: • Demographics and insurance • Flow sheets • Physician Orders Medical History Terms: • Visit notes • CC Chief Complaint of Patient • Laboratory results • HPI History of Present Illness • Radiology results • ROS Review of Systems • Consultant notes • PMHx Past Medical History • Other communications • PSHx Past Surgical History • SHx & FHx Social & Family History Types of Patient Encounter Notes: • Medications and medication allergies • History and Physical • NKDA = no known drug allergies o PE Physical Exam o Lab Laboratory Studies Physical Examination Terms: o Radiology • PE= Physical Exam y x-rays • (+) = present y CT and MRI scans • (-) = Ф = negative or absent y ultrasounds • nl = normal o Assessment- Dx (diagnosis) or • wnl = within normal limits DDx (differential diagnosis) if diagnosis is unclear o R/O = rule out (if diagnosis is Laboratory Terminology: unclear) • CBC = complete blood count o Plan- Further tests, • Chem 7 (or Chem 8, 14, 20) = consultations, treatment, chemistry panels of 7,8,14,or 20 recommendations chemistry tests • The “SOAP” Note • BMP = basic Metabolic Panel o S = Subjective (what the • CMP = complete Metabolic Panel patient tells you) • LFTs = liver function tests o O = Objective (info from PE, • ABG = arterial blood gas labs, radiology) • UA = urine analysis o A = Assessment (Dx and DDx) • HbA1C= diabetes blood test o P = Plan (treatment, further tests, etc.) • Discharge Summary o Narrative in format o Summarizes the events of a hospital stay -

The AOA Guide

The AOA Guide: How to Succeed in the Third-Year Clerkships Example Notes for the MSIII 2014 Preface This guide was created as a way of assisting you as you start your clinical training. For the rest of your professional life you will write various notes, and although they eventually become second nature to you, it is often challenging at first to figure out what information is pertinent to a particular specialty/rotation.This book is designed to help you through that process. In this book you will find samples of SOAP notes for each specialty and a complete History and Physical. Each of these notes represents very typical patients you will see on the rotation. Look at the way the notes are phrased and the information they contain. We have included an abbreviations page at the end of this book so that you can refer to it for the short-forms with which you are not yet familiar. Pretty soon you will be using these abbreviations without a problem! These notes can be used as a template from which you can adjust the information to apply to your patient. It is important to remember that these notes are not all inclusive, of course, and other physicians will give suggestions that you should heed. If you are having trouble, remember there is usually a fourth year medical student on the rotation somewhere, too. We are always willing to help! Table of Contents Internal Medicine Progress Note (SOAP) ............................................................3 Neurology Progress Note (SOAP) ....................................................................... 5 Surgery ................................................................................................................. 7 Progress Note (SOAP) .................................................................................... 7 Pre-Operative Note ........................................................................................ -

The AOA Guide

The AOA Guide: How to Succeed in the Third-Year Clerkships Example Notes for the MSIII 2017 Preface This guide was created as a way of assisting you as you start your clinical training. For the rest of your professional life, you will write various notes. Although they will eventually become second nature to you, it is often challenging at first to figure out what information is pertinent to a particular specialty/rotation.This book is designed to help you through that process. In this book you will find samples of SOAP notes for each specialty and a complete History and Physical. Each of these notes represents very typical patients you will see on the rotation. Look at the way the notes are phrased and the information they contain. We have included an abbre- viations page at the end of this book so that you can refer to it for the short-forms with which you are not yet familiar. Pretty soon you will be using these abbrevia- tions without a problem! These notes can be used as a template from which you can adjust the information to apply to your patient. It is important to remember that these notes are not all inclusive, of course, and other physicians will give sugges- tions that you should heed. If you are ever having trouble, us fourth year medical students are always willing to help! ***NOTE: Many note-writing practices at Jefferson may change as the hospital transitions from paper notes to EMR.*** Table of Contents Internal Medicine Progress Note (SOAP) ............................................................3 Neurology Progress Note (SOAP) ...................................................................... -

SOAP Notes Format in EMR

SOAP Notes Format in EMR SOAP stands for Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan Standard Elements of SOAPnote Date: 08/01/02 Time: Provider: Vital Signs: Height, Weight, Temp, B/P, Pulse S: This ___ yr old fe/male presents for ____ History of Present Illness symptoms: Review Of Symptoms/Systems: (For problem-focused visit, document only pertinent information) Past Medical History: (For problem-focused visit, document only pertinent information) Current Medications: Medication allergies: Social History: (For problem-focused visit, document only pertinent information) Family History: ((For problem-focused visit, document only pertinent information) Genogram: 3 generations with health problems, causes of deaths, etc. or History of major health or genetic disorders in family, including early death, spontaneous abortions or stillbirths. Social History: Past Medical History History of Present Illness: Cultural Background: Hospitalizations: Location: Education Level: Surgical History: Quality Economic Condition: T&A: Severity: Housing: Appendectomy: Duration: Number in household: Hysterectomy: Timing (Onset): Marital Status: Hernia: Timing (Frequency): Lives with: Coronary Artery Bypass: Context: Children: Other: Relieved by: Chronic Medical Problems: Occupation: Hypertension Worsened by: Occupational Health Diabetes Associated signs and symptoms: Hazards: Coronary Heart Disease Nutrition: Cerebrovascular Disease Exercise: Asthma or other COPD Tobacco use: Arthritis Review Of Symptoms (Systems): Constitutional: Caffeine: Gout Sexual activity: -

The SOAP Note and Presentation

The SOAP Note and Presentation Melanie G. Hagen, MD Rebecca R. Pauly, MD University of Florida Use the SOAP Format for all Oral Presentations and Notes z Sometimes the term “SOAP” note is only applied to short notes but the format is used throughout medical practice for communication. z Subjective z Objective z Assessment z Plan SOAP Notes z Subjective z Includes information you have learned from the patient or people caring for the patient. SOAP Notes z Objective z This section includes observations and measurements that you have made during the physical examination. z Includes the vital signs. z Includes a general description of the patient. z Results of diagnostic testing also go here. z Laboratory results z Imaging z Pathology reports SOAP Notes z Assessment z What do you feel is the patient’s differential diagnosis and why? z This is organized by problem or organ system. SOAP Notes z Plan z For each problem what diagnostic testing will you order? z How will you treat each problem? z Medicine z Therapy z Lifestyle change z Tincture of time The Complete Patient Evaluation z Used for new patients in hospital or clinic z History and Physical (H & P) z Complete story of their illness and medical history z Cc and HPI z Past Medical History z Active Medical Problems z Surgical and Trauma History z Childhood Illnesses z Medications and Allergies z Social History z Family History z Review of Systems z Physical Examination z Labs and other diagnostic studies z Assessment z Plan The Progress Note z Uses: z Daily evaluation of a hospitalized -

Preceptor Handbook

Preceptor Handbook Preceptor Handbook Table of Contents Page Number Introduction Introduction to the University ............................................................................................ 1 Introduction to the Program .............................................................................................. 1 Vision and Mission Statements ........................................................................................ 1 Accreditation .................................................................................................................... 2 Curriculum ........................................................................................................................ 2 Preceptor Responsibilities ........................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Experience (CE) Performance Objectives .................................................................. 4 Family Practice .............................................................................................................. 5-8 Internal Medicine ........................................................................................................... 9-13 Emergency Medicine .................................................................................................... 14-18 Pediatrics ..................................................................................................................... 19-22 Psychiatry/Behavioral Medicine ................................................................................... -

Success on the Wards

SUCCESS ON THE WARDS a student-to-student guide to getting the most out of your clinical years AKA “The Purple Book” EDITION 27. 2015. You: (hopefully) by Michelle Au (hopefully not) Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine TABLE OF CONTENTS SUCCESS ON THE WARDS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 4 THE WARD TEAM ............................................................................................... 5 WHAT IS JUNIOR YEAR? ................................................................................... 6 RULES TO LIVE BY ............................................................................................. 8 BASIC CHARTING INFORMATION & TIPS ....................................................... 10 THE CASE PRESENTATION ............................................................................. 13 ADMISSION AND DISCHARGE ........................................................................ 16 THE ROTATIONS .............................................................................................. 19 PRO TIPS FOR THE CORE CLERKSHIPS IN PHASE 2 .................................. 24 MEDICINE ................................................................................................................ 24 SURGERY ............................................................................................................... 31 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY ............................................................................ -

SOAP Note and Wilderness First Aid Guide

Pulse/Pressure Points Wilderness First Aid Reference Cards Carotid Brachial Adapted from: Andrea Andraschko, W-EMT Radial October 2006 Femoral Posterior Dorsalis Tibial Pedis Abdominal Quadrants Airway Anatomy (Looking at Patient) RIGHT UPPER: LEFT UPPER: ANTERIOR: ANTERIOR: GALL BLADDER STOMACH LIVER SPLEEN POSTERIOR: POSTERIOR: R. KIDNEY PANCREAS L. KIDNEY RIGHT LOWER: ANTERIOR: APPENDIX CENTRAL AORTA BLADDER Tenderness in a quadrant suggests potential injury to the organ indicated in the chart. Patient Assessment System SOAP Note Information (Focused Exam) Scene Size-up BLS Pt. Information Physical (head to toe) exam: DCAP-BTLS, MOI Respiratory MOI OPQRST • Major trauma • Air in and out Environmental conditions • Environmental • Adequate Position pt. found Normal Vitals • Medical Nervous Initial Px: ABCs, AVPU Pulse: 60-90 Safety/Danger • AVPU Initial Tx Respiration: 12-20, easy Skin: Pink, warm, dry • Move/rescue patient • Protect spine/C-collar SAMPLE LOC: alert and oriented • Body substance isolation Circulatory Symptoms • Remove from heat/cold exposure • Pulse Allergies Possible Px: Trauma, Environmental, Medical • Consider safety of rescuers • Check for and Stop Severe Bleeding Medications Current Px Resources Anticipated Px → Past/pertinent Hx • # Patients STOP THINK: Field Tx ast oral intake • # Trained rescuers A – Continue with detailed exam L S/Sx to monitor vent leading to incident • Available equipment (incl. Pt’s) VPU – EVAC NOW E Evac level Patient Level of Consciousness (LOC) Shock Assessment Reliable Pt: AVPU Hypovolemic – Low fluid (Tank) Calm A+ Awake and Cooperative Cardiogenic – heart problem (Pump) Comment: Cooperative A- Awake and lethargic or combative Vascular – vessel problem (Hose) If a pulse drops but does not return Sober V+ Responds with sound to verbal to ‘normal’ (60-90 bpm) within 5-25 Alert stimuli Volume Shock (VS) early/compensated minutes, an elevated pulse is likely caused by VS and not ASR.