The Impact of Resource Dependence on the Localization of Humanitarian Action the Case of Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESERT LOCUST UPSURGE Progress Report on the Response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen May–August 2020

DESERT LOCUST UPSURGE Progress report on the response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen May–August 2020 DESERT LOCUST UPSURGE Progress report on the response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen May–August 2020 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 REQUIRED CITATION FAO. 2020. Desert locust upsurge – Progress report on the response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen (May–August 2020). Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ©FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

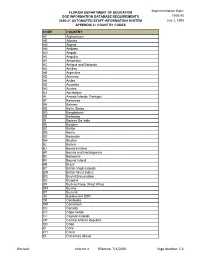

Implementation Date: 1995-95 July 1, 1995 Revised: Volume II Effective: 7

Implementation Date: FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DOE INFORMATION DATABASE REQUIREMENTS 1995-95 2020-21 AUTOMATED STAFF INFORMATION SYSTEM July 1, 1995 APPENDIX C: COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY AF Afghanistan AB Albania AG Algeria AN Andorra AO Angola AV Anguilla AY Antarctica AC Antigua and Barbuda AX Antilles AE Argentina AD Armenia AA Aruba AS Australia AU Austria AJ Azerbaijan AI Azores Islands, Portugal BF Bahamas BA Bahrain BS Baltic States BG Bangladesh BB Barbados BI Bassas Da India BE Belgium BZ Belize BN Benin BD Bermuda BH Bhutan BL Bolivia BJ Bonaire Island BP Bosnia and Herzegovina BC Botswana BV Bouvet Island BR Brazil BT British Virgin Islands BW British West Indies BQ Brunei Darussalam BU Bulgaria BX Burkina Faso, West Africa BM Burma BY Burundi JB Byelorussia SSR CB Cambodia CM Cameroon CC Canada CV Cape Verde CJ Cayman Islands CP Central African Republic CD Chad CI Chile CH China KI Christmas Island Revised: Volume II Effective: 7/1/2020 Page Number: C-1 Implementation Date: FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DOE INFORMATION DATABASE REQUIREMENTS 1995-95 2020-21 AUTOMATED STAFF INFORMATION SYSTEM July 1, 1995 APPENDIX C: COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY CN Clipperton Island KG Cocos Islands (Keeling) CL Colombia CQ Comoros CF Congo CR Coral Sea Island CS Costa Rica DF Croatia CU Cuba DH Curacao Island CY Cyprus CX Czechoslovakia DT Czech Republic DK Democratic Kampuchea DA Denmark DJ Djibouti DO Dominica DR Dominican Republic EJ East Timor EC Ecuador EG Egypt ES El Salvador EN England EA Equatorial Africa EQ Equatorial Guinea -

Annual Report 2020

2020 YEAR IN REVIEW TableofCONTENTS Abbreviations 4 Amref Health Africa at a Glance 9 Message from the Chair, International Board 11 Message from the Group CEO 13 Executive Summary 15 Project Highlights 18 Our Covid-19 Response in Africa 22 Research, Advocacy and Policy Development 23 Capacity Building for Health Workers 24 Supporting Workplaces to ensure Continuity of Economic Activity 24 Supporting flow of Goods and Continuity of Trade between Countries 25 Mobilising and Distributing PPE to Protect Health Workers 25 Water, Sanitation, Hygiene-Infection Prevention and Control (WASH-IPC) 26 Service Delivery 26 Programme Activities 28 Human Resources for Health (HRH) 28 Innovative Health Services and Solutions 35 Investments in Health 48 Crosscutting Themes 53 Policy and Advocacy 53 Research and Innovations 58 Gender and Inclusion 62 Our Subsidiaries 66 Amref Enterprises Limited (AEL) 66 Amref Flying Doctors (AFD) 68 Amref International University (AMIU) 70 Our International Board 72 Our Leadership 72 Our Offices 74 Financial Report 76 ABBREVIATIONS AAC Advocacy Accelerator ACHEST African Centre for Health and Social Transformation AEL Amref Enterprises Limited AHAIC Africa Health Agenda International Conference AMCOA Association of Medical Councils of Africa AMIU Amref International University ANC Antenatal Care ARP Alternative Rite of Passage ASRHR Adolescent, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights AT Assistive Technology ATM Automated Teller Machine ATSM Automated Tuberculosis Screening Machine AWDF African Women’s Development Fund -

Constitutional Reforms and Decentralisation in Kenya, 2000–2020

Marie-Aude Fouéré, Marie-Emmanuelle Pommerolle and Christian Thibon (dir.) Kenya in Motion 2000-2020 Africae Chapter 4 Between Hopes and Disillusionment: Constitutional Reforms and Decentralisation in Kenya, 2000–2020 Chloé Josse-Durand Matteo Réveillon and Sarah Levy Klimpke DOI: 10.4000/books.africae.2480 Publisher: Africae Place of publication: Paris & Nairobi Year of publication: 2021 Published on OpenEdition Books: 8 June 2021 Series: Africae Studies Electronic EAN: 9782957305889 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference JOSSE-DURAND, Chloé. Between Hopes and Disillusionment: Constitutional Reforms and Decentralisation in Kenya, 2000–2020 In: Kenya in Motion 2000-2020 [online]. Paris & Nairobi: Africae, 2021 (generated 23 juin 2021). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/africae/2480>. ISBN: 9782957305889. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.africae.2480. Chapter 4 Between Hopes and Disillusionment Constitutional Reforms and Decentralisation in Kenya, 2000–2020 Chloé Josse-Durand Translated by Matteo Réveillon & Sarah Levy Klimpke In 2010, Kenya made a bold decision: it reformed its constitution by launching a decentralisation—also called devolution—which the World Bank referred to as “ambitious” and “unprecedented” in Africa (World Bank 2012, xi). The exceptional nature of this decentralisation lied not only in its large-scale territorial reform but also in the large number of functions delegated to new local levels of governance, called counties. Each of the new 47 counties was granted a large share of -

Achieving Transformative Results in the Covid-19 Pandemic

PANDEMIC PIVOT: ACHIEVING TRANSFORMATIVE RESULTS IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC 2020 REPORT PANDEMIC PIVOT: ACHIEVING TRANSFORMATIVE RESULTS IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC 2020 REPORT Cover photo: © UNPFA / Arijana K. If we work together in unity and solidarity, these rays of hope can reach around the world. That is the lesson of this most difficult year… both climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic are crises that can only be addressed by everyone together – as part of a transition to an inclusive and sustainable future. … Together, let us make peace among ourselves and with nature, tackle the climate crisis, stop the spread of COVID-19 and make 2021 a year of healing. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres1 1 https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/12/1080962 Message from the Executive Director When a new coronavirus was first identified in December 2019, the pandemic are informing the UNFPA Strategic Plan, 2022– it would have been difficult to imagine the scale of disruption 2025. Young people have played a key role in our outreach in and devastation that virus would ultimately cause. By the end of 2020, providing volunteer support, technological expertise and 2020, more than 82 million people worldwide had been infected technical advice. Data gleaned through rapid assessments and 1.8 million had succumbed to the disease.2 The pandemic and a decades-long history of demographic expertise have has exposed vulnerabilities and exacerbated inequalities within informed rapid response and enabled us to reach the last mile. and between countries, hitting the poorest and most vulnerable Collaboration with radically new partners opened up new paths among us particularly hard. -

HORN-Bulletin-Vol-III-•-Iss-IV-•-July-August-2020.Pdf

Volume III Issue IV July-August 2020 Bulletin The HORN Bulletin is a bi- Historical monthly publication by the HORN Talking Nile: Institute. It contains thematic articles mainly on issues affecting Aspects, Current Concerns, the Horn of Africa region. and the Stalemate in Grand INSIDE Talking Nile: Historical Aspects, 1 Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Current Concerns, and the Stalemate in GERD Negotiations Negotiations Human Rights and COVID-19 11 Responses in the Horn of Africa By Aleksi Ylönen, Ph.D. Burundi in Transition: Nkurunziza’s 20 Legacy and Priority Areas for the Incoming Administration Abstract The Double Edged Sword: China- 29 The iconic Nile River is both historically important and currently significant Kenya Relations in the Wake of COVID-19 Pandemic for the peoples inhabiting territories surrounding it. Ensuring continued access to Nile’s water resources has for a long time been an issue of concern About the HORN Institute especially to those whose livelihoods depend on it in the downstream territories. With independence, securing a sufficient supply of Nile water The HORN International Institute became a national security issue for Egypt and it became the most for Strategic Studies is a non- interested party in the Nile affairs. For years, Egypt, and Sudan as its junior profit, applied research, and partner, worked as the leading states in studying and exploiting the Nile policy think-do tank based water resources. However, with its ambitious dam project on the Blue Nile in Nairobi, Kenya. Its mission which contributes crucially to Nile’s overall flow, Ethiopia rapidly became a is to contribute to informed, contender in Nile affairs. -

Novartis in Society ESG Report 2020 2 | Novartis in Society Contents Novartis in Society | 3

Novartis in Society ESG Report 2020 2 | Novartis in Society CONTENTS Novartis in Society | 3 Contents 2020 highlights 4 Our response to COVID-19 5 Who we are 6 How we create value 8 Message from the Chairman 10 Message from the CEO 11 Our journey to build trust with society 12 Valuing our impact 16 Strategic areas 18 Holding ourselves to high ethical standards 18 Being part of the solution on pricing and access 30 Addressing global health challenges 46 Being a responsible citizen 54 About this report 68 Performance indicators 2020 69 Selected training programs for associates 74 Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) 75 Novartis GRI Content Index 78 Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Index 82 Appendix: corporate responsibility material topic boundaries 84 Appendix: corporate responsibility materiality assessment issue cluster and topic definitions 86 Appendix: external initiatives and membership of associations 88 Appendix: measuring and valuing our impact 89 Independent Assurance Report on the 2020 Novartis in Society ESG reporting 90 Inside cover photo Novartis employees at a production facility in Torre Annunziata, Italy. Cover photo Dr. Ngo Viet Quynh Tram (right) watches as a student practices the correct way to use a mask at the Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy in central Vietnam. Dr. Tram participated in a nationwide effort to train all final-year medical students how to screen, diagnose and treat COVID-19 patients. The program was supported by the Novartis COVID-19 Response Fund. 4 | Novartis -

COVID-19 and Mobility, Conflict and Development in the Horn of Africa

June 2020 COVID-19 and mobility, conflict and development in the Horn of Africa REF briefing paper By Louisa Brain, Hassan Adow, Jama Musse Jama, Farah Manji, Michael Owiso, Fekadu Adugna Tufa, Mahad Wasuge Research and Evidence Facility The Research and Evidence Facility Consortium SOAS, University of London The University of Sahan Thornhaugh St, Manchester Nairobi, Kenya Russell Square, Arthur Lewis Building, www.sahan.global London WC1H 0XG Oxford Road, Conflict & Governance Key United Kingdom Manchester M13 9PL Expert: Vincent Chordi www.soas.ac.uk United Kingdom Senior Advocacy Officer: Team Leader: www.gdi.manchester.ac.uk Rashid Abdi Laura Hammond Migration & Development Research Coordinator: Project Manager and Key Expert: Oliver Bakewell Caitlin Sturridge Research Officer: Communications Manager: Research Team Leader: Louisa Brain Rose Sumner Lavender Mboya This report was prepared by Louisa Brain, Has‐ Suggested Citation: Research and Evidence san Adow, Jama Musse Jama, Farah Manji, Facility (REF). June 2020. ‘COVID‐19 and mo‐ Michael Owiso, Fekadu Adugna Tufa and Ma‐ bility, conflict and development in the Horn of had Wasuge. Africa. REF briefing paper’, London: EU Trust Fund for Africa (Horn of Africa Window) Re‐ This publication was produced with the finan‐ search and Evidence Facility. cial support of the European Union. Its con‐ tents are the sole responsibility of the re‐ For more information on The Research and searchers and do not necessarily reflect the Evidence Facility visit the website views of the European Union or the EU Trust blogs.soas.ac.uk/ref‐hornresearch Fund for Africa. and follow @REFHorn on Twitter. Cover image: © World Bank / Sambrian Funded by the European Union Mbaabu, CC 2.0. -

Effects of COVID-19 Pandemy on African Health, Political and Economic Strategy János Besenyö, Marianna Kármán

Effects of COVID-19 pandemy on African health, political and economic strategy János Besenyö, Marianna Kármán To cite this version: János Besenyö, Marianna Kármán. Effects of COVID-19 pandemy on African health, political and economic strategy. Insights into Regional Development, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Center, 2020, 2 (3), pp.630 - 644. 10.9770/ird.2020.2.3(2). hal-03121408 HAL Id: hal-03121408 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03121408 Submitted on 26 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. INSIGHTS INTO REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT ISSN 2669-0195 (online) http://jssidoi.org/IRD/ 2020 Volume 2 Number 3 (September) http://doi.org/10.9770/IRD.2020.2.3(2) Publisher http://jssidoi.org/esc/home EFFECTS OF COVID-19 PANDEMY ON AFRICAN HEALTH, POLTICAL AND ECONOMIC STRATEGY* János Besenyő ¹, Marianna Kármán ² 1,2 Doctoral School of Safety and Secutity Studies, of Óbuda Uniersity, Hungary E-mails: 1 [email protected]; 2 [email protected] Received 18 March 2020; accepted 10 July 2020; published 30 September 2020 Abstract. The appearance of COVID-19 is proving to be a difficult challenge not only for Africa but for the whole world. -

East Africa Annual Market and Trade Update, 2020

East Africa Annual Market and Trade Update, 2020 WFP VAM | food security analysis Issued: 18 February 2021 Regional Bureau Nairobi Highlights Map 1: Maize price changes: Dec 2020 compared to the five-year average (2015-2019) During 2020, staple food prices generally followed normal seasonal trends except in Sudan where steep rise in prices continued throughout the year. Prices of staple cereals were most elevated in Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Burundi, while they were relatively lower in Uganda and Kenya. Following the COVID-19 related control measures, the region- al cross-border trade reduced significantly in the second quar- ter, which then gradually picked up and slightly surpassed the five-year average level in the last quarter. The recovery in the last two quarters may be attributed to increased exportable regional food surplus and also traders’ adaptations to oper- ating under COVID-19 measures. Livestock prices across the region in 2020 have generally been higher than 2019 and the five-year average, supported by enhanced body conditions following favourable seasonal per- formance. This has enhanced the purchasing power of live- stock keepers. Context 2020 was particularly a difficult year for market dependent households in the region, due to multiple shocks that disrupted food supply chains and impacted livelihoods. Even before the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, food prices were already very high in most markets due to a combination of macro-economic & climatic shocks and effects of localized and protracted conflicts. Despite a generally improved regional annual grain production and surplus, COVID-19 control measures disrupted domestic and cross-border trade and markets resulting in increased food prices and reduced incomes. -

DESERT LOCUST UPSURGE Progress Report on the Response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen May–August 2020

DESERT LOCUST UPSURGE Progress report on the response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen May–August 2020 DESERT LOCUST UPSURGE Progress report on the response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen May–August 2020 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 REQUIRED CITATION FAO. 2020. Desert locust upsurge – Progress report on the response in the Greater Horn of Africa and Yemen (May–August 2020). Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ©FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

Djibouti-Ethiopia-Kenya-And-Uganda

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD3904 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 4.4 MILLION (US$6.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF DJIBOUTI CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 23.1 MILLION (US$31.5 MILLION EQUIVALENT) Public Disclosure Authorized AND GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 23.1 MILLION (US$31.5 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF EURO 39.3 MILLION (US$43.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF KENYA CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 35.2 MILLION (US$48.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR AN EMERGENCY LOCUST RESPONSE PROGRAM AS PHASE 1 OF THE MULTI-PHASE PROGRAMMATIC APPROACH WITH AN OVERALL FINANCING ENVELOPE OF US$500 MILLION EQUIVALENT MAY 7, 2020 Agriculture and Food Global Practice Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Middle East and North Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective {March 31, 2020}) Djibouti Ethiopia Currency Unit = Djiboutian Franc (DJF) Currency Unit = Ethiopian Birr (ETB) DJF177.79 = US$1 ETB32.80 = US$1 Kenya Uganda Currency Unit = Kenyan Shilling (KES) Currency Unit = Ugandan Shilling (UGX) KES105.04 = US$1 UGX3796.50 = US$1 EUR0.91328371 = US$1 SDR 0.73270809 = US$ 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Regional Vice President: Hafez M.