Eliminating Implausible Fisheries Assessment Models Using Fishers’ Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FISH LIST WISH LIST: a Case for Updating the Canadian Government’S Guidance for Common Names on Seafood

FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood Authors: Christina Callegari, Scott Wallace, Sarah Foster and Liane Arness ISBN: 978-1-988424-60-6 © SeaChoice November 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY . 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 Findings . 5 Recommendations . 6 INTRODUCTION . 7 APPROACH . 8 Identification of Canadian-caught species . 9 Data processing . 9 REPORT STRUCTURE . 10 SECTION A: COMMON AND OVERLAPPING NAMES . 10 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 10 Results . 11 Snapper/rockfish/Pacific snapper/rosefish/redfish . 12 Sole/flounder . 14 Shrimp/prawn . 15 Shark/dogfish . 15 Why it matters . 15 Recommendations . 16 SECTION B: CANADIAN-CAUGHT SPECIES OF HIGHEST CONCERN . 17 Introduction . 17 Methodology . 18 Results . 20 Commonly mislabelled species . 20 Species with sustainability concerns . 21 Species linked to human health concerns . 23 Species listed under the U .S . Seafood Import Monitoring Program . 25 Combined impact assessment . 26 Why it matters . 28 Recommendations . 28 SECTION C: MISSING SPECIES, MISSING ENGLISH AND FRENCH COMMON NAMES AND GENUS-LEVEL ENTRIES . 31 Introduction . 31 Missing species and outdated scientific names . 31 Scientific names without English or French CFIA common names . 32 Genus-level entries . 33 Why it matters . 34 Recommendations . 34 CONCLUSION . 35 REFERENCES . 36 APPENDIX . 39 Appendix A . 39 Appendix B . 39 FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood 2 GLOSSARY The terms below are defined to aid in comprehension of this report. Common name — Although species are given a standard Scientific name — The taxonomic (Latin) name for a species. common name that is readily used by the scientific In nomenclature, every scientific name consists of two parts, community, industry has adopted other widely used names the genus and the specific epithet, which is used to identify for species sold in the marketplace. -

Undesirable Substances in Seafood Products – Results from Monitoring Activities in 2006

Undesirable substances in seafood products – Results from monitoring activities in 2006 Ásta Margrét Ásmundsdóttir Vordís Baldursdóttir Sasan Rabieh Helga Gunnlaugsdóttir Matvælaöryggi Skýrsla Matís 17-08 Júlí 2008 ISSN 1670-7192 Titill / Title Undesirable substances in seafood products– results from the monitoring activities in 2006 Höfundar / Authors Ásta Margrét Ásmundsdóttir, Vordís Baldursdóttir, Sasan Rabieh, Helga Gunnlaugsdóttir Skýrsla / Report no. 17 - 08 Útgáfudagur / Date: Júlí 2008 Verknr. / project no. 1687 Styrktaraðilar / funding: Ministry of fisheries Ágrip á íslensku: Árið 2003 hófst, að frumkvæði Sjávarútvegsráðuneytisins, vöktun á óæskilegum efnum í sjávarafurðum, bæði afurðum sem ætlaðar eru til manneldis sem og afurðum lýsis- og mjöliðnaðar. Tilgangurinn með vöktuninni er að meta ástand íslenskra sjávarafurða með tilliti til magns aðskotaefna. Gögnin sem safnað er í vöktunarverkefninu verða einnig notuð í áhættumati og til að hafa áhrif á setningu hámarksgilda óæskilegra efna t.d í Evrópu. Umfjöllun um aðskotaefni í sjávarafurðum, bæði í almennum fjölmiðlum og í vísindaritum, hefur margoft krafist viðbragða íslenskra stjórnvalda. Nauðsynlegt er að hafa til taks vísindaniðurstöður sem sýna fram á raunverulegt ástand íslenskra sjávarafurða til þess að koma í veg fyrir tjón sem af slíkri umfjöllun getur hlotist. Ennfremur eru mörk aðskotaefna í sífelldri endurskoðun og er mikilvægt fyrir Íslendinga að taka þátt í slíkri endurskoðun og styðja mál sitt með vísindagögnum. Þetta sýnir mikilvægi þess að regluleg vöktun fari fram og að á Íslandi séu stundaðar sjálfstæðar rannsóknir á eins mikilvægum málaflokki og mengun sjávarafurða er. Þessi skýrsla er samantekt niðurstaðna vöktunarinnar árið 2006. Það er langtímamarkmið að meta ástand íslenskra sjávarafurða m.t.t. magns óæskilegra efna. Þessu markmiði verður einungis náð með sívirkri vöktun í langan tíma. -

APPENDIX M Common and Scientific Species Names

Bay du Nord Development Project Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX M Common and Scientific Species Names Bay du Nord Development Project Environmental Impact Statement Common and Species Names Common Name Scientific Name Fish Abyssal Skate Bathyraja abyssicola Acadian Redfish Sebastes fasciatus Albacore Tuna Thunnus alalunga Alewife (or Gaspereau) Alosa pseudoharengus Alfonsino Beryx decadactylus American Eel Anguilla rostrata American Plaice Hippoglossoides platessoides American Shad Alosa sapidissima Anchovy Engraulidae (F) Arctic Char (or Charr) Salvelinus alpinus Arctic Cod Boreogadus saida Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Thunnus thynnus Atlantic Cod Gadus morhua Atlantic Halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus Atlantic Mackerel Scomber scombrus Atlantic Salmon (landlocked: Ouananiche) Salmo salar Atlantic Saury Scomberesox saurus Atlantic Silverside Menidia menidia Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrhynchus oxyrhynchus Atlantic Wreckfish Polyprion americanus Barndoor Skate Dipturus laevis Basking Shark Cetorhinus maximus Bigeye Tuna Thunnus obesus Black Dogfish Centroscyllium fabricii Blue Hake Antimora rostrata Blue Marlin Makaira nigricans Blue Runner Caranx crysos Blue Shark Prionace glauca Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis Boa Dragonfish Stomias boa ferox Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis Brown Bullhead Catfish Ameiurus nebulosus Burbot Lota lota Capelin Mallotus villosus Cardinal Fish Apogonidae (F) Chain Pickerel Esox niger Common Grenadier Nezumia bairdii Common Lumpfish Cyclopterus lumpus Common Thresher Shark Alopias vulpinus Crucian Carp -

Real-Time Fish Type Recognition in Underwater Images for Sustainable Fishing

UPTEC IT 14019 Examensarbete 30 hp June 2015 Real-time fish type recognition in underwater images for sustainable fishing Fritjof Jonsson Abstract Real-time fish type recognition in underwater images for sustainable fishing Fritjof Jonsson Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten It has been investigated if it is possible to selectivly catch farmed salmon (Salmo salar L., 1758) and sea Besöksadress: trout (Salmo trutta L., 1758) without disturbing the Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 wild fish. A image analysis software that can Hus 4, Plan 0 separate wild from farmed salmon and salmon from sea trout has been developed. This is interesting Postadress: since the advent of hydro power stations has Box 536 751 21 Uppsala obstructed the natural migration of these species to their natal river streams. Even though ladders have Telefon: been built, fewer fish find their way back up stream. 018 – 471 30 03 This has lead to farming of salmon and sea trout to Telefax: compensate for a lower population. However, this is 018 – 471 30 00 bad for the natural genetic variation and it would be desirable if only the wild fish could enter the rivers. Hemsida: The software could be installed in traps at fish http://www.teknat.uu.se/student ladders to help with this problem. It is common to cut the adipose fin from the farmed salmon and the lack of this fin has been used as a key character to separate farmed from wild salmon. A real-time algorithm was developed which could recognize the farmed fish with high accuracy by searching for presence or absence of the adipose fin. -

Monitoring Bycatches in Norwegian Fisheries

MONITORING BYCATCHES IN NORWEGIAN FISHERIES Species registered by the Norwegian Reference Fleet 2015-2018 Tom Clegg and Tom Williams (IMR) RAPPORT FRA HAVFORSKNINGEN NR. 2020-8 Title (English and Norwegian): Monitoring bycatches in Norwegian fisheries Overvåking av bifangst i Norske fiskerier Subtitle (English and Norwegian): Species registered by the Norwegian Reference Fleet 2015-2018 Arter registrerte av den Norske Referanseflåten 2015-2018 Report series: Year - No.: Date: Distribution: Rapport fra Havforskningen 2020-8 12.03.2020 Open ISSN:1893-4536 Project No.: Authors: 15561 Tom Clegg and Tom Williams (IMR) Program: Godkjent av: Forskningsdirektør(er): Geir Huse Programleder(e): Elena Eriksen Barentshavet og Polhavet Research group(s): Fiskeridynamikk Number of pages: 26 Summary (English): The Norwegian Reference Fleet is a group of active fishing vessels, selected as an approximate stratified random sample of vessels from the Norwegian fishing fleet, and tasked with providing information about catches and general fishing activity to the Institute of Marine Research. Fisheries data is collected by the crew members themselves, an approach commonly known as self-sampling of catches. This report aims to give an overview of how the Norwegian Reference Fleet record their catches and presents the reported catch composition with regards to number of species. A total of 271 species have been recorded by the Norwegian Reference Fleet between 2015 and 2018. There are an additional 39 records of unidentified species, which can occur because of excessive damage limiting an identification or a known misidentification that cannot be rectified. Summary (Norwegian): Referanseflåten er en gruppe aktive fiskefartøy, valgt ut som en tilnærmet stratifisert tilfeldig utvalg (stratified random sample) av fartøy fra den Norske fiskeflåten. -

Intrinsic Vulnerability in the Global Fish Catch

The following appendix accompanies the article Intrinsic vulnerability in the global fish catch William W. L. Cheung1,*, Reg Watson1, Telmo Morato1,2, Tony J. Pitcher1, Daniel Pauly1 1Fisheries Centre, The University of British Columbia, Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory (AERL), 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada 2Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas, Universidade dos Açores, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal *Email: [email protected] Marine Ecology Progress Series 333:1–12 (2007) Appendix 1. Intrinsic vulnerability index of fish taxa represented in the global catch, based on the Sea Around Us database (www.seaaroundus.org) Taxonomic Intrinsic level Taxon Common name vulnerability Family Pristidae Sawfishes 88 Squatinidae Angel sharks 80 Anarhichadidae Wolffishes 78 Carcharhinidae Requiem sharks 77 Sphyrnidae Hammerhead, bonnethead, scoophead shark 77 Macrouridae Grenadiers or rattails 75 Rajidae Skates 72 Alepocephalidae Slickheads 71 Lophiidae Goosefishes 70 Torpedinidae Electric rays 68 Belonidae Needlefishes 67 Emmelichthyidae Rovers 66 Nototheniidae Cod icefishes 65 Ophidiidae Cusk-eels 65 Trachichthyidae Slimeheads 64 Channichthyidae Crocodile icefishes 63 Myliobatidae Eagle and manta rays 63 Squalidae Dogfish sharks 62 Congridae Conger and garden eels 60 Serranidae Sea basses: groupers and fairy basslets 60 Exocoetidae Flyingfishes 59 Malacanthidae Tilefishes 58 Scorpaenidae Scorpionfishes or rockfishes 58 Polynemidae Threadfins 56 Triakidae Houndsharks 56 Istiophoridae Billfishes 55 Petromyzontidae -

Sebastes Fasciatus

Acadian Redfish − Sebastes fasciatus Overall Vulnerability Rank = Moderate Biological Sensitivity = Moderate Climate Exposure = High Data Quality = 83% of scores ≥ 2 Expert Data Expert Scores Plots Scores Quality (Portion by Category) Sebastes fasciatus Low Moderate Stock Status 2.0 2.8 High Other Stressors 1.9 2.2 Very High Population Growth Rate 3.5 2.4 Spawning Cycle 2.6 2.8 Complexity in Reproduction 1.9 1.2 Early Life History Requirements 2.2 2.0 Sensitivity to Ocean Acidification 1.1 0.8 Prey Specialization 2.0 3.0 Habitat Specialization 1.5 3.0 Sensitivity attributes Sensitivity to Temperature 2.2 3.0 Adult Mobility 2.8 2.0 Dispersal & Early Life History 1.8 2.8 Sensitivity Score Moderate Sea Surface Temperature 3.9 3.0 Variability in Sea Surface Temperature 1.0 3.0 Salinity 1.1 3.0 Variability Salinity 1.2 3.0 Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Variability Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Variability in Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Ocean Acidification 4.0 2.0 Exposure variables Variability in Ocean Acidification 1.0 2.2 Currents 2.1 1.0 Sea Level Rise 1.1 1.5 Exposure Score High Overall Vulnerability Rank Moderate Acadian Redfish (Sebastes fasciatus) Overall Climate Vulnerability Rank: Moderate (94% certainty from bootstrap analysis). Climate Exposure: High. Two exposure factors contributed to this score: Ocean Surface Temperature (3.9) and Ocean Acidification (4.0). All life stages of Acadian Redfish use marine habitats. Biological Sensitivity: Moderate. Three sensitivity attributes scored above 2.5: Population Growth Rate (3.5), Spawning Cycle (2.6), Adult Mobility (2.8). -

TAB 05 RM 66 DFO Redfish to The

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: X Decision: Issue: Information regarding the possible addition of the Acadian Redfish (Sebastes fasciatus) and the Deepwater Redfish (Sebastes mentella) to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk on the Species at Risk Act. Background: As per 3.3 of the Harmonized Listing Process, DFO is informing NWMB of assessment results. COSEWIC has completed status updates for the Acadian Redfish and Deepwater Redfish. DFO does not intend to move forward with listing consultations for species that occur in both Nunavut and Nunavik waters until an MOU has been developed and approved to harmonize the SARA listing process and Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement. This means the SARA listing process will not move forward at this time for the Acadian and Deepwater Redfish. Acadian Redfish and Deepwater Redfish – General Because the two species cannot be easily distinguished (Fig. 1), DFO Fisheries Management treats the two species as a single management unit. For this reason, the two species have been assessed together by COSEWIC in the 2010 report and both have been designated as Threatened. Redfish inhabit cold waters along slopes of banks and channels at a depth of 100 to 700 m. Deepwater Redfish are typically found in waters of 350 to 700 m depth while Acadian Redfish prefer slightly shallower waters of from 150 t0 300 m. While Deepwater Redfish occur on both sides of the Atlantic, the Acadian Redfish is found only in the western Atlantic, mainly along the coast of Canada (Figure 2). Redfish have a long life span (up to at least 75 years) and late maturation and slow growth give this species low resilience and are considered limiting factors. -

Agilent RFLP Decoder

Agilent Reference Database AB 1 Species Common name 2 Clupea harengus Atlantic herring 3 Dicentrarchus labrax European sea bass 4 Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod 5 Gadus morhua Atlantic cod 6 Glyptocephalus cynoglossus Witch 7 Hippoglossus stenolepis Pacific halibut 8 Kathetostoma giganteum Giant stargazer 9 Katsuwonus pelamis Skipjack tuna 10 Lophiodes caulinaris Spottedtail angler 11 Lophius americanus Monkfish/American angler 12 Lophius budegassa Monkfish/Black-bellied angler 13 Lophius piscatorius Monkfish/Anglerfish 14 Lophius vaillanti Shortspine African angler 15 Lophius vomerinus Cape monkfish/Cape anglerfish 16 Macruronus novaezelandiae New Zealand hoki 17 Melanogrammus aeglefinus Haddock 18 Merlangius merlangus Whiting 19 Merluccius hubbsi Argentine hake 20 Merluccius merluccius European hake 21 Merluccius paradoxus Deep water cape hake 22 Microstomus kitt Lemon sole 23 Molva molva Ling 24 Mullus surmuletus Striped red mullet 25 Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii Cut-throat trout 26 Oncorhynchus gorbuscha Pink/Humpback salmon 27 Oncorhynchus keta Keta/Chum salmon 28 Oncorhynchus kisutch Coho/Silver salmon 29 Oncorhynchus masou masou Cherry salmon 30 Oncorhynchus nerka Red/Sockeye salmon 31 Oncorhynchus tshawytscha Chinook/King/Pacific salmon 32 Pangasianodon hypophthalmus Pangasius/Basa/River cobbler 33 Platichthys flesus Flounder 34 Pleuronectes platessa European plaice 35 Pollachius pollachius Pollock 36 Pollachius virens Coley/Saithe 37 Psetta maxima Turbot 38 Reinharditius hippoglossoides Greenland halibut 39 Salmo salar Atlantic -

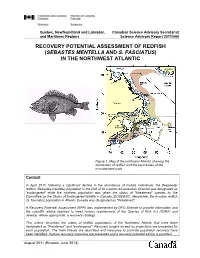

Recovery Potential Assessment of Redfish (Sebastes Mentella and S

Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat and Maritimes Regions Science Advisory Report 2011/044 RECOVERY POTENTIAL ASSESSMENT OF REDFISH (SEBASTES MENTELLA AND S. FASCIATUS) IN THE NORTHWEST ATLANTIC Figure 1. Map of the northwest Atlantic showing the distribution of redfish and the boundaries of the management units Context In April 2010, following a significant decline in the abundance of mature individuals, the Deepwater redfish (Sebastes mentella) population in the Gulf of St. Lawrence/Laurentian Channel was designated as "endangered" while the northern population was given the status of "threatened" species by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Meanwhile, the Acadian redfish (S. fasciatus) population in Atlantic Canada was designated as "threatened". A Recovery Potential Assessment (RPA) was implemented by DFO Science to provide information and the scientific advice required to meet various requirements of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) and develop, where appropriate, a recovery strategy. This advice describes the status of redfish populations of the Northwest Atlantic that have been designated as "threatened" and "endangered". Recovery targets as well as projections are presented for each population. The main threats are described and measures to promote population recovery have been identified. Various recovery scenarios are presented and a recovery potential advice is provided. August 2011 (Erratum: June 2013) Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Recovery Potential Assessment of Redfish and Maritimes Regions (Sebastes fasciatus and S. mentella) in the Northwest Atlantic SUMMARY • COSEWIC identified two designatable units (DU) for deepwater redfish (Sebastes mentella): Gulf of St. Lawrence/Laurencian Channel (Unit 1+2) and northern population (SA0+2+3KLNO). -

Icelandic Golden Redfish Commercial Fishery

FAO-Based Icelandic Responsible Fisheries Management Golden Redfish Full Assessment Report FAO-BASED ICELANDIC RESPONSIBLE FISHERY MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION FULL ASSESSMENT REPORT For The Icelandic Golden Redfish Commercial Fishery Applicant Group: The Federation of Icelandic Fishing Vessel Owners (LÍÚ) The Federation of Icelandic Fish Processing Plants (SF) The National Association of Small Boat Owners, Iceland (NASBO) Fisheries Association of Iceland (Facilitator) SAI Global/Global Trust Certification Ltd. Head Office, 3rd Floor, Block 3, Quayside Business Park, Mill Street, Dundalk, Co. Louth. T: +353 42 9320912 F: +353 42 9386864 web: www.GTCert.com Report Ref: ICE/RED/001/2013 Page 1 of 193 FAO-Based Icelandic Responsible Fisheries Management Golden Redfish Full Assessment Report Report Ref: ICE/RED/001/2013 Page 2 of 193 FAO-Based Icelandic Responsible Fisheries Management Golden Redfish Full Assessment Report Assessment Team Members Clare Murray, Lead Assessor SAI Global/Global Trust Certification Ltd. Dundalk, Ireland. Gísli Svan. Einarsson, Assessor VERIÐ Vísindagarðar/Science Park Háeyri 1. 550 Sauðárkrókur. Iceland. Dr. Norman Graham, Assessor Marine Institute, Galway, Ireland. Deirdre Hoare, Assessor Independent Fishery Scientist, Dublin, Ireland. Report Ref: ICE/RED/001/2013 Page 3 of 193 FAO-Based Icelandic Responsible Fisheries Management Golden Redfish Full Assessment Report Schedule of Key Assessment Activities: Assessment Activities Date (s) Application Date May 2011 Initial Review January 2012 Initial Site Visit June 2012 Validation Assessment Report February 2012 Appointment of Full Assessment Team June 2012 On-site Assessment Visit December 2012 Draft Full Assessment Report August 2013* Client Review October 2013* External Peer Review March 2014** Final Assessment Report April 2014 Certification Review/Decision May 1st 2014 *Report awaiting confirmation of outcome on ICES Redfish HCR Review **Report awaiting implementation of Icelandic Redfish Fisheries Management Plan HCR. -

Deepwater Redfish/Acadian Redfish Complex Sebastes Mentella and Sebastes Fasciatus

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Deepwater Redfish/Acadian Redfish complex Sebastes mentella and Sebastes fasciatus Deepwater Redfish Gulf of St. Lawrence - Laurentian Channel Population Deepwater Redfish Northern Population Acadian Redfish Atlantic Population Acadian Redfish Bonne Bay Population in Canada Deepwater Redfish Gulf of St. Lawrence - Laurentian Channel Population – ENDANGERED Deepwater Redfish Northern Population – THREATENED Acadian Redfish Atlantic Population – THREATENED Acadian Redfish Bonne Bay Population – SPECIAL CONCERN 2010 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Deepwater Redfish/Acadian Redfish complex Sebastes mentella and Sebastes fasciatus, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 80 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Red Méthot for writing the status report on the Deepwater Redfish/Acadian Redfish complex Sebastes mentella and Sebastes fasciatus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Alan Sinclair, Co-Chair of the COSEWIC Marine Fishes Specialist Subcommittee, and Howard Powles, previous Co-Chair of the COSEWIC Marine Fishes Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le complexe sébaste atlantique/ sébaste d’Acadie (Sebastes mentella et Sebastes fasciatus) au Canada.