Finance and Managerial Control in the US Forest Products Industry, 1945-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolute Forest Products Annual Report 2021

Resolute Forest Products Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NYSE:RFP) Published: March 1st, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER: 001-33776 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0526415 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. employer identification number) 111 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard Suite 5000 Montreal Quebec Canada H3C 2M1 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (514) 875-2160 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: New York Stock Exchange Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share RFP Toronto Stock Exchange (Title of class) (Trading Symbol) (Name of exchange on which registered) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

AFIO Periscope

NEWSLETTER OF AFIO NATIONAL AND CHAPTER ™ PERISCOPE EVENTS, PLANS & NEWS Association of Former Intelligence Offi cers olumeV XXVI, Number 1, 2003 Boston Pops Meets the Men in Black Special AFIO Evening Hosted by Albano F. Ponte FIO recently held a ground-breaking event in Boston at The Changing Face Symphony Hall on of Intelligence Tuesday,A July 2, 2003. The Boston Pops Esplanade Orchestra performed AFIO’s to a sold-out performance including one hundred AFIO members and National Intelligence supporters and AFIO President Gene Symposium 2003 Poteat, all of whom enjoyed a program titled An American Salute. at The National Reconnaissance Office, The Central Intelligence Agency, and other locales 1 - 4 November 2003 — Tyson’s Corner, VA Backstage post-concert were [L to R] AFIO Board member & ave the date! And make plane Symposium 2003 will be com- Endowment Fund Director Albano Ponte; Boston Pops conductor bined with the AFIO Convention and Keith Lockhart; AFIO President Gene Poteat, and AFIO Member and hotel reservations NOW. and Chairman of Boston Pops Event Committee Gary Wass.. The AFIO National Intelli- Awards Banquet again this year, but the gence Symposium 2003, 1 Banquet will start the event. The AFIO Conductor Keith Lockhart, led Sthrough 4 November 2003, will be Convention runs 1 and 2 November at the Boston Pops in a stirring patri- one of our best ever, with distinguished the Sheraton Premiere Hotel on Lees- otic program of American favorites speakers from the intelligence commu- burg Pike in Tysons Corner, Virginia. with guest performers soprano Indra nity, law enforcement, and homeland The Sixth Annual AFIO Awards Ban- Thomas and Pianist Michael Lewin. -

Public Opinion and Foreign Policy ∗ John Peterson 1

9 L a í t { 5 Ç 9 t h C t W t 1 US Democrats = the True Europeans? Public Opinion and Foreign Policy ∗ John Peterson 1 This paper, based on a ceremonial lecture, develops three main arguments. First, we know far more today about public opinion globally than we have ever known before. Second, foreign policy is becoming a less cloistered, elite- dominated arena of public policy. Third, all of this has implications for transatlantic relations. On most questions of values – including those which underpin US foreign policy – Americans are more alike than different from one another, and both exceptional and distinct from Europeans. On questions of policy, the real divide is often not between Europe and America, but between American Republicans and everybody else. One consequence of the polarisation of American society is that American Democrats share many views on policy that are ‘European’ in nature. Over the years, all of us who have studied European integration have learned a lot from Joseph Weiler of New York University. Over those same years, he has developed and kept close ties to the University of Edinburgh, mostly via the good offices of our highly-prized colleague Prof Drew Scott of the Europa Institute. A few years ago, I saw Weiler give a ceremonial lecture in Belfast. On that occasion, I felt that I learned a lot about what is appropriate at this sort of occasion. By way of introducing him, the person chairing in Belfast elected to read out a very long list of all of the academic institutions where Joseph had ever been affiliated. -

Building the Resolute of the Future

BUILDING THERESOLUTE resolutefpcom OFTHEFUTURE AnnualReport SHAREHOLDERINFORMATION ANNUALGENERALMEETING INVESTORRELATIONS FORMK Ourannualmeetingofstockholders AlainBourdages ResoluteForestProductsIncfi lesits willbeheldonWednesdayJune VicePresident annualreportonFormKwiththeUS atamEastern atCentredesarts SecuritiesandExchangeCommission deBaieComeaudeBretagne ir resolutefpcom acopyofwhichisincludedwiththis BaieComeauQuebecG C S annualreporttostockholders Canada MEDIA Freecopieswithoutexhibits are availableuponrequesttoResolute’s TRANSFERAGENT SethKursman InvestorRelationsdepartment FORCOMMONSTOCK VicePresident Thecompany’sSECfi lingsannualreports CorporateCommunications ResoluteForestProductsisaglobal Acommitmenttosustainabilityisatthe ComputershareTrustCompanyNA tostockholdersnewsreleasesandother SustainabilityandGovernmentAff airs BUILDING leaderintheforestproductsindustry heartofourcompanycultureItguides POBox CollegeStation investorinformationcanbeaccessedat withadiverserangeofproducts ourapproachtothewaywedobusiness Texas UnitedStates resolutefpcom/investors sethkursman resolutefpcom THERESOLUTE includingmarketpulpwoodproducts everydayWetakeenormouspride tollfreewithin tissuenewsprintandspecialtypapers inthesupportwehavereceivedfrom theUnitedStatesandCanada STOCKLISTINGS OFTHEFUTURE Thecompanyownsoroperates communityandFirstNationsleaders INVESTORINFORMATION overpulppaperwoodproducts customersunionrepresentatives Thesharesofcommonstockof computersharecom/investor ANDFINANCIALREPORTING andtissuefacilitiesintheUnited governmentoffi -

Forest Products Forest Annual Market Annual Review 2014-2015

UNECE Forest Products Forest Annual MarketAnnual Review 2014-2015 UNECE Forest Products - Annual Market Review 2014-2015 UNITED NATIONS UNECE Forest Products Annual Market Review 2014-2015 II UNECE/FAO Forest Products Annual Market Review, 2014-2015 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Data for the Commonwealth of Independent States is composed of these twelve countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or carry the endorsement of the United Nations. ABSTRACT The Forest Products Annual Market Review 2014-2015 provides a comprehensive analysis of markets in the UNECE region and reports on the main market influences outside the UNECE region, using the best-available data from diverse sources. It covers the range of products from the forest to the end-user: from roundwood and primary-processed products to value-added products and those used in housing. Statistics-based chapters analyse the markets for wood raw materials, sawn softwood, sawn hardwood, wood- based panels, paper, paperboard and woodpulp. Other chapters analyse policies, institutional forestland ownership and its effects on forest products markets, and markets for wood energy. The Review highlights the role of sustainable forest products in international markets. -

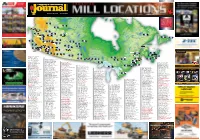

Mill Location Map Is Complete and Up-To-Date

www.forestnet.com — 604.990.9970 Every effort has been made to ensure that the information on this mill location map is complete and up-to-date. Possible errors and omissions are inevitable and we ask that these be brought to Logging & Sawmilling Journals attention. Please Fort Nelson contact [email protected] with updated information. Map Source file National Atlas of Canada. Fort Smith “Source: © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. High Level Prince Rupert G LSJ PUBLISHING Terrace Fort St. John Smithers Peace River Goose Bay Fort McMurray Grande Prairie Prince George Gander St. John’s Quesnel Slave Lake Port Hardy Hinton Thompson Williams Lake La Ronge Edmonton Flin Flon Campbell River Loydminster The Pas Kamloops Prince Albert Revelstoke Nanaimo Vancouver Kelowna Calgary Saskatoon ® ® NEED A LIFT? Charlottetown Cranbrook Dolbeau-Mistanssini Lethbridge Medicine Hat Dauphin Regina Moncton British Columbia Board Mills Truro Atco Wood Products Ltd. • Fruitvale • 250-367-9441 Kapuskasing BC Veneer Products Ltd. • Surrey • 604-572-8968 Halifax CIPA Lumber Co. Ltd. • Delta • 604-523-2250 Brandon Kenora Quebec St. John Coastland Wood Industries Ltd. • Nanaimo • 250-754-1962 Canwest Trading Ltd. (Suncoast Lumber & Milling) • Sechelt • 604-885-7313 Dryden Val d´Or Winnipeg Eldcan Forest Products Ltd. • Kamloops • 250-573-1900 Capital Woodwork • Langley • 604-607-5697 Timmins Gorman Bros. Lumber Ltd. • Canoe • 250-833-1260 Carrier Lumber Ltd. • Prince George • 250-563-9271 Louisiana-Pacific Canada Ltd. • Dawson Creek • 250-782-1616 Chimney Creek Lumber Co. Ltd. • Williams Lake • 250-392-7267 Trois-Riviéres Louisiana-Pacific Canada Ltd. • Golden • 250-344-8846 Conifex (Fort St. -

Troubled Waters Earthquakes May Not Be Oklahoma’S Biggest Problem with Fracking

• An Independent JournAl of CommentAry • JUNE 2016 • VOLUME 48 NUMBER 6 • $5.00 Troubled Waters Earthquakes May Not Be Oklahoma’s Biggest Problem With Fracking Special Report: Page 24 Observations www.okobserver.net OK Corral VOLUME 48, NO. 6 Chalk one up for common sense. The same Legislature that introduced a resolution urging the presi- PUBLISHER Beverly Hamilton dent’s impeachment and approved a measure [later vetoed] making abor- EDITOR Arnold Hamilton tion a felony actually stood up to the gun lobby and rejected a proposal that would have authorized open-carry without training or permits. DIGITAL EDITOR MaryAnn Martin Holy Slim Pickens! What in the Wide, Wide World of Sports is a-goin’ on here? FOUNDING EDITOR Frosty Troy Well, it turns out modern businesses – including the NBA’s Oklahoma ADVISORY BOARD City Thunder – weren’t exactly keen on Grandfield Republican Rep. Jeff Marvin Chiles, Andrew Hamilton, Coody’s loopy, frontier-era scheme to allow anyone at least 21 years old Matthew Hamilton, Scott J. Hamilton, and without a felony conviction to strap on a firearm, whether or not Trevor James, Ryan Kiesel, George Krumme, Robert D. Lemon, they know the barrel from the handle. Gayla Machell, Bruce Prescott, It was in late April, you might recall, that a licensed, conceal-carrying Robyn Lemon Sellers, Kyle Williams man shot and killed a fellow worshipper at a Pennsylvania church in a dispute over reserved seating. OUR MOTTO To Comfort the Afflicted and Afflict the If that can happen in a house of worship, just imagine untrained, un- Comfortable. licensed, intoxicated louts at an emotionally-charged Bedlam football game, six-shooters at the ready. -

We Are Resolute

WE ARE RESOLUTE 2010SUSTAINABILITy reporT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 RENEWED 1.1 COMPANY PROFILE 5 1.2 REPORT HIGHLIGHTS 6 1.3 LETTER FROM THE CEO 9 1.4 ABOUT THIS REPORT 11 1.5 SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY AND KEY COMMITMENTS 15 2 RESPONSIBLE 2.1 FIBER AND FORESTRY 18 2.2 CLIMATE AND ENERGY 26 2.3 MILL ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE 34 2.4 PRODUCTS 44 2.5 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 50 2.6 GOVERNANCE AND CORPORATE CULTURE 56 2.7.1 EMPLOYEES / HUMAN RESOURCES 61 2.7.2 EMPLOYEES / HEALTH AND SAFETY 64 2.8 COMMUNITY 70 2.9 ECONOMIC IMPACTS 76 3 RESOLUTE 3.1 MILL ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCEA DAT 80 3.2 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) INDEX 88 3.3 GLOSSARY 93 2 FOREST REGENERATION The regeneration of harvested areas is an essential component of sustainable forest management. As a responsible forest manager, Resolute seeks to respect the natural growth cycle of trees, while ensuring biodiversity. In Canada, fiber used in our products is sourced primarily from public land, located mainly in the boreal forest. By law, these woodlands must be promptly regenerated. The boreal forest has a remarkable ability to regenerate on its own. In fact, approximately 75% of the area harvested grows back naturally. Our foresters ensure that the rest is promptly reforested. We planted a total of 62.7 million seedlings in 2010. To put the impact of the forest products industry in per- disturbed annually by wildfires, insects and disease. The spective, it should be noted that approximately 0.2% of series of time-stamped images that follow are represen- the boreal forest is harvested by the industry each year.1 tative of the typical regeneration of a black spruce forest By comparison, five times this amount on average is found in the northern Lac-Saint-Jean, Québec, region. -

2011 Annual Report

RESOLUTE FO r EST P r ODUCTS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT2011 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Printed in Canada resolutefp.com RESOLUTE_RAP_COVER_ANG_R1.indd 1 05/04/12 12:16 FINANCIAL BOard of DIRECTORS HIGHLIGHTS Richard B. EVANS JEFFREy A. HEARN 2, 4 Michael S. ROUSSEAU 1, 3 1 Audit Committee Non-Executive Chairman, Corporate Director Executive Vice President 2 Environmental, Health 0 1 and Safety Committee AbitibiBowater Inc. 1, 3 and Chief Financial Officer, Alain RHÉAUME 3 LETter tO Air Canada Finance Committee Richard GARNEAU Managing Partner, 4 Human Resources and SHAREHOLDERS 2, 4, President and Trio Capital Inc. DAvid H. Wilkins Compensation/Nominating and Governance Committee Chief Executive Officer, 3, 4, 5 Partner, Nelson Mullins Riley & AbitibiBowater Inc. PAul C. RIVETT Scarborough LLP; Former U.S. 5 Not standing for re-election at Vice President and Ambassador to Canada the May 23, 2012, annual meeting 02 1, 2, 3 Richard D. FALCONER Chief Legal Officer, Fairfax of stockholders EXECUTIVE Corporate Director Financial Holdings Limited 04 TEAM EXECUTIVE OFFICERS RESOLUTE AT A GLANCE Richard GARNEAU Pierre LABERGE YVEs LAFLAMME JACQUEs P. VACHON President and Senior Vice President, Senior Vice President, Wood Senior Vice President, Chief Executive Officer Human Resources Products, Procurement and Corporate Affairs and 05 Information Technology Chief Legal Officer Alain Boivin John LAFAVE PRODUCT Senior Vice President, Senior Vice President, Jo-Ann LONgwORTH OVERVIEW Pulp and Paper Operations Pulp and Paper Sales Senior Vice President and 06 and Marketing Chief Financial Officer NEW IDENTITY Shareholder INFORMATION ANNUal General MEETING MEDIA 08 Seth KURSMAN Our annual meeting of stockholders will be held Vision and on Wednesday, May 23, 2012, at 8:00 AM (Eastern), Vice President, Corporate Communications, VALUES at the Hilton Charlotte Center City, North Carolina Room, Sustainability and Government Relations 3rd Floor, 222 East Third Street, Charlotte, North Carolina. -

Bands’ Rocks out for Children Who Stutter Transportation to the Individual Events Will Be Provided at No Cost

News Sports Students get backstage Women’s tennis loses pass to entertainment tournament opener, beats world with PRSSA 3 UCR for ninth place 6 California State University, Fullerton DAILY TITAN Tuesday, April 26, 2005 www.dailytitan.com Volume 80, Issue 39 Creative strategy puts ad team in third team the victory yesterday during at the competition, it was this cliff- eight other schools in their district The National Student Advertising Farnall said the presentation was Synergy 23 competes the National Student Advertising hanger that left him hanging when and received third place for their Competition included over 200 evaluated by five judges, two of against seven schools Competition on campus. making his decision. presentation. schools, said Olan Farnall, an asso- whom were from Yahoo!, this year’s Their idea was to produce a “cliff- “The idea is there but I’m not Greg Dodds, a co-account super- ciate professor and Ad Club faculty client. in Yahoo! campaign hanger” advertisement that viewers sure whether the world is ready,” visor for the UCLA advertising team, adviser. There are 15 separate dis- Businesses typically pay approxi- By ASHLEE ANDRIDGE could go to the Web to watch, and said Roberts. “It was a struggle. Not said the answer to their success was tricts and the winner from each com- mately $1.5 million to be a host Daily Titan Asst. News Editor in the end, they hoped it would help everyone’s got broadband.” hard work. petes nationally in Nashville, Tenn., for the competition and sometimes them stand out from other schools, First place for the competition “We’re a club, not a class. -

2017 Annual and Sustainability Report

2017 ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT resolutefp.com 1 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS — 2017 ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT A REWARDING CULTURE Over the past six years, Resolute In recognition of our industry-leading Forest Products has emerged as a sustainability, environmental and safety performance, Resolute won over 20 regional, global sustainability leader, working North American and international awards and closely with employees, retirees, union distinctions in the past year alone. representatives, customers, business We value this recognition because it provides and Aboriginal partners, community tangible proof that our vision and values are not leaders, government officials, and merely aspirational words; they are the driving force behind our improved performance and industry peers on issues that matter to global success. The awards garnered in 2017 us all: protecting the natural resources speak directly to our core values of working safely, in our care, mitigating climate change, being accountable, ensuring sustainability and investing in clean sources of energy succeeding together. Our achievements in sustainable development as well as our and deepening our commitment to business practices reflect the principled Aboriginal peoples. Our vision and leadership of our management team values capture our business approach and the hard work and dedication and our shared sense of purpose, of our employees. guiding our business decisions, actions and behaviors. Our success is linked to a rewarding culture, where profitability and sustainability