Special Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro to Google for the Hill

Introduction to A company built on search Our mission Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. As a first step to fulfilling this mission, Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed a new approach to online search that took root in a Stanford University dorm room and quickly spread to information seekers around the globe. The Google search engine is an easy-to-use, free service that consistently returns relevant results in a fraction of a second. What we do Google is more than a search engine. We also offer Gmail, maps, personal blogging, and web-based word processing products to name just a few. YouTube, the popular online video service, is part of Google as well. Most of Google’s services are free, so how do we make money? Much of Google’s revenue comes through our AdWords advertising program, which allows businesses to place small “sponsored links” alongside our search results. Prices for these ads are set by competitive auctions for every search term where advertisers want their ads to appear. We don’t sell placement in the search results themselves, or allow people to pay for a higher ranking there. In addition, website managers and publishers take advantage of our AdSense advertising program to deliver ads on their sites. This program generates billions of dollars in revenue each year for hundreds of thousands of websites, and is a major source of funding for the free content available across the web. Google also offers enterprise versions of our consumer products for businesses, organizations, and government entities. -

1592213370-Monetize.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Online Monetization: How to Turn Your Following into Cash 1.1 What is monetization? 1.2 How to monetize your website, blog, or social media channel 1.3 Does a monetization formula exist? Chapter 1 Takeaways 2. How to Monetize Your Blog The Right Way 2.1 Why should you start monetizing with your blog? 2.2 How to earn money from blogging 2.3 How to transform your blog visitors into loyal fans 2.4 Blog monetization tools you should know about Chapter 2 Takeaways 3. Facebook Monetization: The What, Why, Where, and How 3.1 How Facebook monetization works 3.2 Facebook monetization strategies Chapter 3 Takeaways 4. How to monetize your Instagram following 4.1 Before you go chasing that Instagram money... 4.2 The four main ways you can earn money on Instagram 4.3 Instagram monetization tools 4.4 Ideas to make money on Instagram Chapter 4 Takeaways 5. Monetizing a YouTube Brand Without Ads 5.1 How to monetize Youtube videos without Adsense 5.2 Essential Youtube monetization tools 5.3 Factors that determine your channel’s long-term success Chapter 5 Takeaways 1. Online Monetization: How to Turn Your Following into Cash 5 Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Jenn, a customer service agent at a car leasing company, is fed up with her job. Her pay’s lousy, she’s on edge with customers yelling at her over the phone all day (they actually treat her worse in person), and her boss ignores all her suggestions, even though she knows he could make her job a lot less stressful. -

Google Ad Tech

Yaletap University Thurman Arnold Project Digital Platform Theories of Harm Paper Series: 4 Report on Google’s Conduct in Advertising Technology May 2020 Lissa Kryska Patrick Monaghan I. Introduction Traditional advertisements appear in newspapers and magazines, on television and the radio, and on daily commutes through highway billboards and public transportation signage. Digital ads, while similar, are powerful because they are tailored to suit individual interests and go with us everywhere: the bookshelf you thought about buying two days ago can follow you through your favorite newspaper, social media feed, and your cousin’s recipe blog. Digital ads also display in internet search results, email inboxes, and video content, making them truly ubiquitous. Just as with a full-page magazine ad, publishers rely on the revenues generated by selling this ad space, and the advertiser relies on a portion of prospective customers clicking through to finally buy that bookshelf. Like any market, digital advertising requires the matching of buyers (advertisers) and sellers (publishers), and the intermediaries facilitating such matches have more to gain every year: A PwC report estimated that revenues for internet advertising totaled $57.9 billion for 2019 Q1 and Q2, up 17% over the same half-year period in 2018.1 Google is the dominant player among these intermediaries, estimated to have netted 73% of US search ad spending2 and 37% of total US digital ad spending3 in 2019. Such market concentration prompts reasonable questions about whether customers are losing out on some combination of price, quality, and innovation. This report will review the significant 1 PricewaterhouseCoopers for IAB (October 2019), Internet Advertising Revenue Report: 2019 First Six Months Results, p.2. -

Google Adsense Fuels Growth for Android- Focused Site

Google AdSense Case Study Google AdSense fuels growth for Android- focused site About elandroidelibre • elandoidelibre.com • Based in Madrid • Blog about the Android operating system “We regard AdSense as an essential tool that’s helping us to set up more blogs, take on more staff, and earn more revenue.” — Paolo Álvarez, administrator and editor. elandroidelibre.com (“the free Android”) is a leading Spanish-language blog about the Android operating system, featuring news, reviews, games and other apps for Android smartphone users. Launched in 2009, it now employs six people and attracts 6.5 million visits each month. Since the outset, Google AdSense has accounted for around 40 per cent of its income. Administrator and editor Paolo Álvarez says: “I was attracted to AdSense because it was simple and effective. I began using it right from the start, and even though I wasn’t an expert, I could see that it worked.” He’s highly satisfied with the quality and relevance of the ads appearing on his site, and says the 300 x 250 Medium Rectangle and the 728 x 90 Leaderboard formats work particularly well. Álvarez uses Google AdSense reports and Google Analytics to analyse the return on the site and gain a better understanding of the kind of visitors it attracts: for example 30 per cent of traffic and income comes from mobile devices. He has also begun using Google’s free ad serving solution, DoubleClick for Publishers, allowing him to manage his online advertising more effectively and segment traffic from different countries. He plans to continue improving the quality and quantity of content in the future. -

Google Data Collection —NEW—

Digital Content Next January 2018 / DCN Distributed Content Revenue Benchmark Google Data Collection —NEW— August 2018 digitalcontentnext.org CONFIDENTIAL - DCN Participating Members Only 1 This research was conducted by Professor Douglas C. Schmidt, Professor of Computer Science at Vanderbilt University, and his team. DCN is grateful to support Professor Schmidt in distributing it. We offer it to the public with the permission of Professor Schmidt. Google Data Collection Professor Douglas C. Schmidt, Vanderbilt University August 15, 2018 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Google is the world’s largest digital advertising company.1 It also provides the #1 web browser,2 the #1 mobile platform,3 and the #1 search engine4 worldwide. Google’s video platform, email service, and map application have over 1 billion monthly active users each.5 Google utilizes the tremendous reach of its products to collect detailed information about people’s online and real-world behaviors, which it then uses to target them with paid advertising. Google’s revenues increase significantly as the targeting technology and data are refined. 2. Google collects user data in a variety of ways. The most obvious are “active,” with the user directly and consciously communicating information to Google, as for example by signing in to any of its widely used applications such as YouTube, Gmail, Search etc. Less obvious ways for Google to collect data are “passive” means, whereby an application is instrumented to gather information while it’s running, possibly without the user’s knowledge. Google’s passive data gathering methods arise from platforms (e.g. Android and Chrome), applications (e.g. -

Broadband Video Advertising 101

BROADBAND VIDEO ADVERTISING 101 The web audience’s eyes are already on broadband THE ADVERTISING CHALLENGES OF video, making the player and the surrounding areas the ONLINE PUBLISHERS perfect real estate for advertising. This paper focuses on what publishers need to know about online advertising in Why put advertising on your broadband video? When order to meet their business goals and adapt as the online video plays on a site, the user’s attention is largely drawn advertising environment shifts. away from other content areas on the page and is focused on the video. The player, therefore, is a premium spot for advertising, and this inventory space commands a premium price. But adding advertising to your online video involves a lot of moving parts and many decisions. You need to consider the following: • What types and placements of ads do you want? • How do you count the ads that are viewed? • How do you ensure that the right ad gets shown to the right viewer? Luckily, there are many vendors that can help publishers fill up inventory, manage their campaigns, and get as much revenue from their real estate as possible. This paper focuses on the online advertising needs of the publisher and the services that can help them meet their advertising goals. THE VIDEO PLATFORM COMCASTTECHNOLOGYSOLUTIONS.COM | 800.844.1776 | © 2017 COMCAST TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS ONLINE VIDEO ADS: THE BASICS AD TYPES You have many choices in how you combine ads with your content. The best ads are whatever engages your consumers, keeps them on your site, and makes them click. -

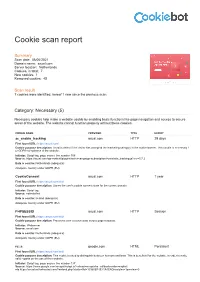

Cookie Scan Report

Cookie scan report Summary Scan date: 08/06/2021 Domain name: axual.com Server location: Netherlands Cookies, in total: 7 New cookies: 1 Removed cookies: 45 Scan result 7 cookies were identified, hereof 1 new since the previous scan. Category: Necessary (5) Necessary cookies help make a website usable by enabling basic functions like page navigation and access to secure areas of the website. The website cannot function properly without these cookies. COOKIE NAME PROVIDER TYPE EXPIRY ac_enable_tracking axual.com HTTP 29 days First found URL: https://axual.com/ Cookie purpose description: Used to detect if the visitor has accepted the marketing category in the cookie banner. This cookie is necessary f or GDPR-compliance of the website. Initiator: Script tag, page source line number 508 Source: https://axual.com/wp-content/plugins/activecampaign-subscription-forms/site_tracking.js?ver=5.7.2 Data is sent to: Netherlands (adequate) Adequate country under GDPR (EU) CookieConsent axual.com HTTP 1 year First found URL: https://axual.com/trial/ Cookie purpose description: Stores the user's cookie consent state for the current domain Initiator: Script tag Source: notinstalled Data is sent to: Ireland (adequate) Adequate country under GDPR (EU) PHPSESSID axual.com HTTP Session First found URL: https://axual.com/trial/ Cookie purpose description: Preserves user session state across page requests. Initiator: Webserver Source: axual.com Data is sent to: Netherlands (adequate) Adequate country under GDPR (EU) rc::a google.com HTML Persistent First found URL: https://axual.com/trial/ Cookie purpose description: This cookie is used to distinguish between humans and bots. -

GOOGLE ADVERTISING TOOLS (FORMERLY DOUBLECLICK) OVERVIEW Last Updated October 1, 2019

!""!#$%%&'($)*+,+-!%*""#,%%%./")0$)#1%%'"23#$4#+456%"($)(+$7%%% #89:%%2;<8:=<%">:?@=A%BC%%%DEBF% " #$%%$&'("&)"*+,-./$(-.("0(-"1&&2%-"3*.4-/$'2"/&&%("/&"5%*6-"*+("*%&'2($+-"1&&2%-""""""""""""""(-.,$6-(7" (-*.68".-(0%/(7"&."&'"/8$.+"5*./9":-;($/-(<"1&&2%-"*%(&"%-,-.*2-("$/(",*(/"(/&.-("&)"0(-."+*/*"/"""""""""""""" &" 5.&,$+-"*+,-./$(-.(":$/8"(&58$(/$6*/-+"="*'+"&)/-'"0'6*''9"="$'($28/("$'/&"/8-$."*+("" """"""""" >" 5-.)&.3*'6-<""" " % 5$1%&'($)*+,% $)G/&4+-!%H)"'24*,%%% " 1&&2%-"#*.4-/$'2"?%*/)&.37"""""""5.-,$&0(%9"4'&:'"*("@&0;%-A%$647"$("1&&2%-" >("5.-3$03"*+,-./$(-.B" )*6$'2"5.&+06/<"1&&2%-"*6C0$.-+""""@&0;%-A%$64"$'"DEEF"")&."GH<!";$%%$&'7"3&.-"/8*'"G!";$%%&'"""""""&,-." /8-"(-%""""""""""""""%-.I(",*%0*/$&'<!"J/"/8-"/$3-7"@&0;%-A%$64":*("*"%-*+$'2"5.&,$+-."&)"+$(5%*9"*+("/&"5&50%*." /8$.+"5*./9"($/-("%$4-"" " " "" JKL7"#9M5*6-7"*'+"/8-"N*%%"M/.--/"O&0.'*%< " " " " " D""""P'"DE!Q7"1&&2%-"0'$)$-+"" @&0;%-A%$64>("*+,-./$(-."/&&%("*'+"$/("-'/-.5.$(-"*'*%9/$6("5.&+06/"0'+-""""""" ."/8-""""1&&2%-"#*.4-/$'2" ?%*/)&.3";.*'+<""H" " J("*"5*./"&)"/8-"DE!Q".-;.*'+$'2"""" 7"1&&2%-"""*%(&".-68.$(/-'-+"$/(""""5.&+06/("/8*/"*%%&:-+"":-;"" 50;%$(8-.("/&"(-%%"*+,-./$($'2"(5*"""" 6-7")&.3-.%9"4'&:'"*(""""""""@&0;%-A%$64")&."?0;%$(8-.("*'+" @&0;%-A%$64""""""""J+"RS68*'2-<"J%/8&028"/8-(-"5.&+06/("*.-"'&:"";.*'+-+"*("1&&2%-"J+"#*'*2-."""" 7" @&0;%-A%$64""6&+-" "(/$%%"*55-*.("&'"T<U"3$%%$&'":-;($/-(< " " " " "T" "" " !""#$%&'()*%& +,-#&.$(+/")0&123&!&& ""#$%&452&& & 1&&2%-"#*.4-/$'2"?%*/)&.3"$("/8-"5.-3$03"6&0'/-.5*./"/&"1&&2%-I(")%*2(8$5"*+"50.68*($'2""""""" -

Ei-Report-2013.Pdf

Economic Impact United States 2013 Stavroulla Kokkinis, Athina Kohilas, Stella Koukides, Andrea Ploutis, Co-owners The Lucky Knot Alexandria,1 Virginia The web is working for American businesses. And Google is helping. Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. Making it easy for businesses to find potential customers and for those customers to find what they’re looking for is an important part of that mission. Our tools help to connect business owners and customers, whether they’re around the corner or across the world from each other. Through our search and advertising programs, businesses find customers, publishers earn money from their online content and non-profits get donations and volunteers. These tools are how we make money, and they’re how millions of businesses do, too. This report details Google’s economic impact in the U.S., including state-by-state numbers of advertisers, publishers, and non-profits who use Google every day. It also includes stories of the real business owners behind those numbers. They are examples of businesses across the country that are using the web, and Google, to succeed online. Google was a small business when our mission was created. We are proud to share the tools that led to our success with other businesses that want to grow and thrive in this digital age. Sincerely, Jim Lecinski Vice President, Customer Solutions 2 Economic Impact | United States 2013 Nationwide Report Randy Gayner, Founder & Owner Glacier Guides West Glacier, Montana The web is working for American The Internet is where business is done businesses. -

Google-Doubleclick Case

Statement of FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Concerning Google/DoubleClick FTC File No. 071-0170 The Federal Trade Commission has voted 4-11 to close its investigation of Google’s proposed acquisition of DoubleClick after a thorough examination of the evidence bearing on the transaction. The Commission dedicated extensive resources to this investigation because of the importance of the Internet and the role advertising has come to play in the development and maintenance of this rapidly evolving medium of communication.2 Online advertising fuels the diversity and wealth of free information available on the Internet today. Our investigation focused on the impact of this transaction on competition in the online advertising marketplace. The investigation was conducted pursuant to the Commission’s statutory authority under the Clayton Act to review mergers and acquisitions. If this investigation had given the Commission reason to believe that the transaction was likely to harm competition and injure consumers, the Commission could have filed a federal court action seeking to enjoin the transaction under Section13(b) of the Federal Trade Commission Act (“FTC Act”) and Section 15 of the Clayton Act. The standard used by the Commission to review mergers and acquisitions is set forth in Section 7 of the Clayton Act. That statute prohibits acquisitions or mergers, the effect of which “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” The Commission can apply Section 7 (as well as Section 1 of the Sherman Act and Section 5 of the FTC Act) to challenge transactions that threaten to create, enhance, or facilitate the exercise of market power. -

Google Adsense •Doubleclick •MSN.Com •Yahoo Publisher •Valueclick Network •AOL.Com •Aquantive •Quigo •Ask.Com •24/7 Real Media

DefiningDefining thethe RelevantRelevant ProductProduct MarketMarket forfor GoogleGoogle-- DoubleClickDoubleClick MergerMerger Robert W. Hahn, Reg-Markets Hal J. Singer, Criterion Economics IndustryIndustry BackgroundBackground InIn 2007,2007, U.S.U.S. advertisersadvertisers werewere expectedexpected forfor thethe firstfirst timetime toto spendspend moremore onon onlineonline advertisingadvertising thanthan onon radioradio advertisingadvertising • Source: eMarketer U.S.U.S. onlineonline advertisingadvertising revenuesrevenues inin 20072007 werewere roughlyroughly $17$17 billion,billion, anan increaseincrease ofof 3535 percentpercent overover 20052005 revenuesrevenues • Source: Interactive Advertising Bureau 2 TheThe InputsInputs toto anan OnlineOnline AdAd Suppliers of online advertising provide three primary inputs: (1) ad tools, (2) intermediation, and (3) publisher tools Ad tools: software packages that allow advertisers to manage inventory and produce ads Intermediation: matching advertisers (buyers) to publishers (sellers) in an advertising marketplace • publishers’ direct sales forces • “ad networks” (resell publisher ad space) • “ad exchanges” (match advertisers and publishers) 3 ResearchResearch AgendaAgenda OurOur analysisanalysis focusesfocuses onon whetherwhether differentdifferent channelschannels ofof onlineonline advertisingadvertising representrepresent aa singlesingle productproduct marketmarket Limitation:Limitation: WeWe dodo notnot analyzeanalyze whetherwhether otherother formsforms ofof advertisingadvertising -

Understanding In-App Header Bidding: the Essentials

UNDERSTANDING IN-APP HEADER BIDDING THE ESSENTIALS INTRODUCTION Consumers downloaded 204 billion apps in 2019,1 as users around the world shifted to mobile-first browsing behaviors. This shift in user behavior has driven advertisers to follow their customers into app environments, creating a booming opportunity for app developers. Three key trends have impacted how advertisers have changed their investing strategies to give mobile publishers a unique opportunity: 1 MOBILE AD SPEND IS ON THE RISE Digital ad spend was expected to surpass traditional media, including TV, for the first time in 2019,2 with the majority of digital ad spend going to mobile devices (including both mobile web and in-app). 2 BRANDS PREFER TO BUY APPS PROGRAMMATICALLY Programmatic strategies tend to get a larger portion of in-app advertising budgets. On average, 66% of in-app budgets go to programmatic direct or open exchange strategies as compared to 34% for direct buy.3 As a result, mobile advertising now accounts for the majority of global programmatic ad spend, with over 80% of all programmatic display dollars in the US and UK going to mobile.4 3 PROGRAMMATIC IN-APP BUDGETS ARE GROWING As buyers shift their spend to mobile channels, programmatic in-app is experiencing some of the biggest opportunities. Recent research found that 30% of buyers planned to grow their programmatic direct in-app budgets by more than 10% the following year.5 As mobile advertising continues to grow, app publishers who want to scale effectively and get a slice of growing brand dollars will embrace programmatic selling through header bidding.