On the Phenomena of the Glacial Drift of Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography: Example Erosion

The Physical and Human Causes of Erosion The Holderness Coast By The British Geographer Situation The Holderness coast is located on the east coast of England and is part of the East Riding of Yorkshire; a lowland agricultural region of England that lies between the chalk hills of the Wolds and the North Sea. Figure 1 The Holderness Coast is one of Europe's fastest eroding coastlines. The average annual rate of erosion is around 2 metres per year but in some sections of the coast, rates of loss are as high as 10 metres per year. The reason for such high rates of coastal erosion can be attributed to both physical and human causes. Physical Causes The main reason for coastal erosion at Holderness is geological. The bedrock is made up of till. This material was deposited by glaciers around 12,000 years ago and is unconsolidated. It is made up of mixture of bulldozed clays and erratics, which are loose rocks of varying type. This boulder clay sits on layer of seaward sloping chalk. The geology and topography of the coastal plain and chalk hills can be seen in figure 2. Figure 2 The boulder clay with erratics can be seen in figure 3. As we can see in figures 2 and 3, the Holderness Coast is a lowland coastal plain deposited by glaciers. The boulder clay is experiencing more rapid rates of erosion compared to the chalk. An outcrop of chalk can be seen to the north and forms the headland, Flamborough Head. The section of coastline is a 60 kilometre stretch from Flamborough Head in the north to Spurn Point in the south. -

Newtown Linford Village Design Statement 2008

Newtown Linford Village Design Statement 2008 Newtown Linford Village Design Statement 2008 Contents Title Page Executive summary 2-6 The Purpose of this Village Design Statement 7 1. Introduction 8 The purpose and use of this document. Aims and objectives 2. The Village Context 9-10 Geographical and historical background The village today and its people Economics and future development 3. The Landscape Setting Visual character of the surrounding countryside 11-12 Relationship between the surrounding countryside and the village periphery Landscape features Buildings in the landscape 4. Settlement Pattern and character 13-15 Overall pattern of the village Character of the streets and roads through the village Character and pattern of open spaces 5. Buildings & Materials in the Village 16-26 1. The challenge of good design 2. Harmony, the street scene 3. Proportions 4. Materials 5. Craftsmanship 6. Boundaries 7. Local Businesses 8. Building guidelines 6. Highways and Traffic 27-29 Characteristics of the roads and Footpaths Street furniture, utilities and services 7. Wildlife and Biodiversity 30-32 8. Acknowledgments 33 9. Appendix 1 Map of Village Conservation Area 34 Listed Buildings in the Village 35 10. Appendix 2 Map of the SSSI & Local Wildlife Sites 36 Key to the SSSI & Local Wildlife Sites 37-38 “Newtown Linford is a charming place with thatched and timbered dwellings, an inviting inn and a much restored medieval church in a peaceful setting by the stream - nor is this all, for the village is the doorstep to Bradgate Park, one of Leicestershire’s loveliest pleasure grounds,... … … with the ruins of the home of the ill fated nine days queen Lady Jane Grey” Arthur Mee - “Leicestershire” - Hodder and Stoughton. -

Holderness Coast (United Kingdom)

EUROSION Case Study HOLDERNESS COAST (UNITED KINGDOM) Contact: Paul SISTERMANS Odelinde NIEUWENHUIS DHV group 57 Laan 1914 nr.35, 3818 EX Amersfoort PO Box 219 3800 AE Amersfoort The Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)33 468 37 00 Fax: +31 (0)33 468 37 48 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] 1 EUROSION Case Study 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA 1.1 Physical process level 1.1.1 Classification One of the youngest natural coastlines of England is the Holderness Coast, a 61 km long stretch of low glacial drift cliffs 3m to 35m in height. The Holderness coast stretches from Flamborough Head in the north to Spurn Head in the south. The Holderness coast mainly exists of soft glacial drift cliffs, which have been cut back up to 200 m in the last century. On the softer sediment, the crumbling cliffs are fronted by beach-mantled abrasion ramps that decline gradually to a smoothed sea floor. The Holderness coast is a macro-tidal coast, according to the scoping study the classification of the coast is: 2. Soft rock coasts High and low glacial sea cliffs 1.1.2 Geology About a million years ago the Yorkshire coastline was a line of chalk cliffs almost 32 km west of where it now is. During the Pleistocene Ice Age (18,000 years ago) deposits of glacial till (soft boulder clay) were built up against these cliffs to form the new coastline. The boulder clay consists of about 72% mud, 27% sand and 1% boulders and large Fig. -

Section 3: the Fishes of the Tweed and the Eye

SECTION 3: THE FISHES OF THE TWEED AND THE EYE C.2: Beardie Barbatulus Stone Loach “The inhabitants of Italy ….. cleaned the Loaches, left them some time in oil, then placed them in a saucepan with some more oil, garum, wine and several bunches of Rue and wild Marjoram. Then these bunches were thrown away and the fish was sprinkled with Pepper at the moment of serving.” A recipe of Apicius, the great Roman writer on cookery. Quoted by Alexis Soyer in his “Pantropheon” published in 1853 Photo C.2.1: A Beardie/Stone Loach The Beardie/Stone Loach is a small, purely freshwater, fish, 140mm (5.5”) in length at most. Its body is cylindrical except near the tail, where it is flattened sideways, its eyes are set high on its head and its mouth low – all adaptations for life on the bottom in amongst stones and debris. Its most noticeable feature is the six barbels set around its mouth (from which it gets its name “Beardie”), with which it can sense prey, also an adaptation for bottom living. Generally gray and brown, its tail is bright orange. It spawns from spring to late summer, shedding its sticky eggs amongst gravel and vegetation. For a small fish it is very fecund, one 75mm female was found to spawn 10,000 eggs in total in spawning episodes from late April to early August. The species is found in clean rivers and around loch shores throughout west, central and Eastern Europe and across Asia to the Pacific coast. In the British Isles they were originally found only in the South-east of England, but they have been widely spread by humans for -

Charnwood Forest

Charnwood Forest: A Living Landscape An integrated wildlife and geological conservation implementation plan March 2009 Cover photograph: Warren Hills, Charnwood Lodge Nature Reserve (Michael Jeeves) 2 Charnwood Forest: A Living Landscape Contents Page 1. Executive summary 5 2. Introduction 8 3. A summary of the geological/geomorphological interest 13 4. Historical ecology since the Devensian glaciation 18 5. The main wildlife habitats 21 6. Overall evaluation 32 7. Summary of changes since the 1975 report 40 8. Review of recommendations in the 1975 report 42 9. Current threats 45 10. Existing nature conservation initiatives 47 11. New long-term objectives for nature conservation in Charnwood Forest 51 12. Action plan 54 13. Acknowledgements 56 14. References 57 Appendix – Gazeteer of key sites of ecological importance in Charnwood Forest Figures: 1. Charnwood Forest boundaries 2. Sites of Special Scientific Interest 3. Map showing SSSIs and Local Wildlife Site distribution 4. Tabulation of main geological formations and events in Charnwood 5. Regionally Important Geological Sites 6. Woodlands in order of vascular plant species-richness 7. Moth species-richness 8. Key sites for spiders 9. Key sites for dragonflies and damselflies 10. Evaluation of nature conservation features 11. Invertebrate Broad Assemblage Types in Charnwood listed by ISIS 12a Important ISIS Specific Assemblage Types in Charnwood Forest 3 12b Important habitat resources for invertebrates 12c Important sites for wood-decay invertebrate assemblages 12d Important sites for flowing water invertebrate assemblages 12e Important sites for permanent wet mire invertebrate assemblages 12f Important sites for other invertebrate assemblage types 13. Evaluation of species groups 14. Leicestershire Red Data Book plants 15. -

Institute of Hydrology

Institute of Hydrology Natural Environment Research Council • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 0-0 • • • • • • • •-atsZICI_t 73- eTard2 - • • • • • • • • Hydrological and Hydrogeological Assessment • Cransley Lodge, Kettering for • Stock Land and Estates Ltd • Volume 1 This repon is an official document prepared under contract between Stock Land and Estates Ltd and the Natural Environment Research CounciL It should not be quoted without permission of both the Institute of Hydrology and Stock Land Estates Ltd. • • Institute of Hydrology Maclean Building Crowmarsh Gifford Wall ingford 0 Oxon OXIO 8BB 0 UK Tel: 0491 38800 0 Telex: 849365 Hydro] G • March 1992 Fax: 0491 32256 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •-• • • • • • • • \, Contents VOLUME 1 Figures Glossary of Terms Summary • 1 INTRODUCTION 2 SITE DESCRIPTION AND STUDY OUTLINE 2.1 Location 2.2 Artificial Influences 2.2.1 Ironstone Quarries 2.2.2 Augmented Spring Flow 2.2.3 Agricultural Practices 2.3 Monitoring Network 3 GEOLOGY • 3.1 Jurassic Deposits 3.1.1 Upper Lias 3.1.2 Northampton Sand 3.1.3 Upper Estuarine Series 3.2 Pleistocene Deposits 3.2.1 Pleistocene Gravel 3.2.2 Boulder Clay 3.3 Recent Deposits 4 HYDROGEOLOGY 4.1 Jurassic Deposits 4.1.1 Upper Lias 4.1.2 Northampton Sand 4.1.3 Upper Estuarine Series 4.2 Pleistocene Deposits 4.2.1 Pleistocene Gravel 4.2.2 Boulder Clay 4.3 Recent Deposits • • 7a2 ;$,:gnIC.,;;aarttr:rm:::=1;ram:moz • 5 SURFACE HYDROLOGY • 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Catchment Description 5.3 Flood Frequency Analysis 5.3.1 Statistical -

PLANTS of PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-County 78)

PLANTS OF PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-county 78) A CHECKLIST OF FLOWERING PLANTS AND FERNS David J McCosh 2012 Cover photograph: Sedum villosum, FJ Roberts Cover design: L Cranmer Copyright DJ McCosh Privately published DJ McCosh Holt Norfolk 2012 2 Neidpath Castle Its rocks and grassland are home to scarce plants 3 4 Contents Introduction 1 History of Plant Recording 1 Geographical Scope and Physical Features 2 Characteristics of the Flora 3 Sources referred to 5 Conventions, Initials and Abbreviations 6 Plant List 9 Index of Genera 101 5 Peeblesshire (v-c 78), showing main geographical features 6 Introduction This book summarises current knowledge about the distribution of wild flowers in Peeblesshire. It is largely the fruit of many pleasant hours of botanising by the author and a few others and as such reflects their particular interests. History of Plant Recording Peeblesshire is thinly populated and has had few resident botanists to record its flora. Also its upland terrain held little in the way of dramatic features or geology to attract outside botanists. Consequently the first list of the county’s flora with any pretension to completeness only became available in 1925 with the publication of the History of Peeblesshire (Eds, JW Buchan and H Paton). For this FRS Balfour and AB Jackson provided a chapter on the county’s flora which included a list of all the species known to occur. The first records were made by Dr A Pennecuik in 1715. He gave localities for 30 species and listed 8 others, most of which are still to be found. Thereafter for some 140 years the only evidence of interest is a few specimens in the national herbaria and scattered records in Lightfoot (1778), Watson (1837) and The New Statistical Account (1834-45). -

THE Various Deposits of Boulder-Clay, Sands, Gravels, Brick-Earths, Warp

Downloaded from http://pygs.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Saskatchewan on March 17, 2015 KAIKLEY : BLOWING WELLS. 421 attention has been drawn to them, In this paper it is shown—That these currents vary in nature and amount with the changes of the barometer just as the volume of the air in any closed receiver varies strictly with the atmospheric pressure when the influence of temperature has been eliminated. Hence the observations may be considered to prove the existence of large cavities or series of cavities or fissures in the underlying strata adjacent to the wells. In the case of the well at Solberge, this cavity has a capacity approximating to ten millions of cubic feet. A chamber 217 feet each way—length, width, and height, would have nearly the same capacity. GLACIAL SECTIONS AT YOEK, AND THEIR RELATION TO LATER DEPOSITS. BY J. EDMUND CLARK, B.A., B.SC, ETC. THE various deposits of boulder-clay, sands, gravels, brick-earths, warp and peat, near York, have been sufficiently exposed by build• ing operations, brick fields, and gravel pits to show this very simple relation. Resting upon the deep-seated Triassic rocks lies the irregular boulder-clay, which forms all the higher ground, reaching in Severn's Mount to 100 feet above the river Ouse. Where the stream escapes from between its undulations, the top• most laj^ers have been washed and re-arranged as glacial gravels. Its hollows have been levelled up with the sediment thus pro• duced, forming the brick-earths and warpy clays; whilst peat deposits have completed the work where the depth, elevation, or remoteness of the original hollow prevented the brick-earths from accomplishing that end. -

Solway Tweed RBMP Chapter 2: Appendices a and B

The river basin management plan for the Solway Tweed river basin district 2009–2015 Chapter 2 Appendices A and B Contents Appendix A: Water bodies with extended deadlines for achieving good status 2 Appendix B: Water bodies with a lower (less stringent) objective than good status 25 Appendix A: Water bodies with extended deadlines for achieving good status WBID NAME Assessment category Water use Assessment 2015 2021 2027 parameter 5101 Whiteadder Water flow and water Abstraction - manufacturing Change from Moderate by Good by Water (Dye levels natural flow 2015 2021 Water to Billie conditions Burn Water flow and water Flow regulation - aquaculture Change from Moderate by Good by confluences) levels natural flow 2015 2021 conditions Water flow and water Flow regulation - manufacturing Change from Moderate by Good by levels natural flow 2015 2021 conditions Water flow and water Flow regulation - public water Change from Moderate by Good by levels supplies natural flow 2015 2021 conditions 5105 Blackadder General water quality Diffuse source pollution - Phosphorus Moderate by Good by Water (Howe agriculture 2015 2021 Burn confluence General water quality Point source pollution - collection Phosphorus Moderate by Good by to Whiteadder and treatment of sewage 2015 2021 Water) Water flow and water Abstraction - agriculture Change from Moderate by Good by levels natural flow 2015 2021 conditions Water flow and water Abstraction - agriculture Depletion of base Moderate by Good by levels flow from gw body 2015 2021 5109 Howe Burn General water -

Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report

.. Natural Environment Research Councii Institute of Geological Sciences Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report p-_- A report prepared for the Department of Industry This report relates to workcarried out by the Institute of Geological Sciences on behalf of the Department of Industry. The information contained herein must not be published without reference to the Director, Institute of Geological Sciences D. Ostle Programme Manager Institute of Geological Sciences Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG No. 28 A mineral reconnaissance survey of the Abington-Biggar-Moffat area, south-central Scotland INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES Natural Environment Research Council Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report No. 28 A mineral reconnaissance survey of the Abington-Biggar-Moffat area, south-central Scotland. South Lowlands Unit J. Dawson, BSc J. D. Floyd, BSc, PhD P. R. Philip, BSc 0 Crown copyright 1979 London 1979 A report prepared for the Department of Industry Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Reports The Institute of Geological Sciences was formed by the incorporation of the Geological Survey of Great Britain and 1 The concealed granite roof in south-west Cornwall the Geological Museum with Overseas Geological Surveys and is a constituent body of the Natural Environment 2 Geochemical and geophysical investigations around Research Council Garras Mine, near Truro, Cornwall 3 Molybdenite mineralisation in Precambrian rocks near Lairg, Scotland 4 Investigation of copper mineralisation at Vidlin, Shetland 5 Preliminary mineral reconnaissanceof Central Wales 6 Report on geophysical surveys at Struy, Inverness- shire 7 Investigation of tungsten and other mineralisation associated with the Skiddaw Granite near Carrock Mine, Cumbria 8 Investigation of stratiform sulphide mineralisation in parts of central Perthshire 9 Investigation of disseminated copper mineralisation near Kilmelford, Argyllshire, Scotland 10 Geophysical surveys around Talnotry mine, Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland 11 12 Mineral investigations in the Teign Valley, Devon. -

Copy of List of Public Roads

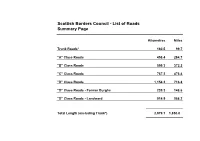

Scottish Borders Council - List of Roads Summary Page Kilometres Miles Trunk Roads* 160.5 99.7 "A" Class Roads 458.4 284.7 "B" Class Roads 599.3 372.2 "C" Class Roads 767.2 476.4 "D" Class Roads 1,154.2 716.8 "D" Class Roads - Former Burghs 239.3 148.6 "D" Class Roads - Landward 914.9 568.2 Total Length (excluding Trunk*) 2,979.1 1,850.0 Trunk Roads (Total Length = 160.539 km or 99.695 Miles) Classification / Route Description Section Length Route No. A1 London-Edinburgh- From boundary with Northumberland at Lamberton Toll to boundary with 29.149 km 18.102 miles Thurso East Lothian at Dunglass Bridge A7 Galashiels-Carlisle From the Kingsknowe roundabout (A6091) by Selkirk and Commercial 46.247 km 28.719 miles Road, Albert Road and Sandbed, Hawick to the boundary with Dumfries & Galloway at Mosspaul. A68 Edinburgh-Jedburgh- From boundary with Midlothian at Soutra Hill by Lauder, St. Boswells and 65.942 km 40.95 miles Newcastle Jedburgh to Boundary with Northumberland near Carter Bar at B6368 road end A702 Edinburgh-Biggar- From Boundary with Midlothian at Carlops Bridge by West Linton to 10.783 km 6.696 miles Dumfries Boundary with South Lanarkshire at Garvald Burn Bridge north of Dolphinton. A6091 Melrose Bypass From the Kingsknowe R'bout (A7) to the junction with the A68 at 8.418 km 5.228 miles Ravenswood R'bout "A" Class Roads (Total Length = 458.405 km or 284.669 Miles) Classification / Description Section Length Route Route No. A7 Edinburgh-Galashiels- From the boundary with Midlothian at Middleton by Heriot, Stow and 31.931 km 19.829 miles Carlisle Galashiels to the Kingsknowe R'bout (A6091) A1107 Hillburn-Eyemouth- From A1 at Hillburn by Redhall, Eyemouth and Coldingham to rejoin A1 at 21.509 km 13.357 miles Coldingham-Tower Tower Farm Bridge A697 Morpeth-Wooler- From junction with A698 at Fireburnmill by Greenlaw to junction with A68 38.383 km 23.836 miles Coldstream-Greenlaw- at Carfraemill. -

T H E T W E E D P O U R S It S W a T E R S a F a R D O W N T H E L In

1 The Tw eed pours its w aters afar D ow n the links on yon w ild, w inding glen A nd the m ountains look up to the stars R ound the haunt and the dw ellings of m en H enry Scott R iddell Plate 1 The confluence of the River Tweed and Biggar Water looking to Drumelzier Frontispiece 2 Dedication This survey is dedicated to the memory of Andrew Lorimer Farmer of Mossfennan, Tweedsmuir Andrew Lorimer contacted the writer of this report and asked if a survey of Mossfennan Farm would be possible, since he knew of numerous unrecorded sites. The writer was invited to walk over the farm with Mr Lorimer who did indeed point out sites without record and also the monuments that had been recorded. The farm, like the other areas of Upper Tweeddale has a rich legacy of upstanding buildings, covering a range of periods. That visit was one of the reasons for the present research of the archaeological sites and monuments of Upper Tweeddale. To facilitate a survey, Mr Lorimer sketch painted a view of Logan, depicting the sites he knew about. This was presented to the writer and is produced here for the first time. Sadly, Andrew Lorimer did not live to see the outcome of what he desired. However, this survey of Upper Tweeddale, the land he loved so much, could not have been reproduced in the form it is, without a generous grant from the Andrew Lorimer Trust. The writer acknowledges that essential support and is grateful to the Trustees of the Fund for their confidence in the outcome of this work, of which the survey is the first phase.