The Election of 2004 – Collective Memory Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Clinton Bibliography - 2002 Thru 2020*

Bill Clinton Bibliography - 2002 thru 2020* Books African American Journalists Rugged Waters: Black Journalists Swim the Mainstream by Wayne Dawkins PN4882.5 .D38 2003 African American Women Cotton Field of Dreams: A Memoir by Janis Kearney F415.3.K43 K43 2004 For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Politics by Donna Brazile E185.96 .B829 2018 African Americans--Biography Step by Step: A Memoir of Hope, Friendship, Perseverance, and Living the American Dream by Bertie Bowman E185.97 .B78 A3 2008 African Americans--Civil Rights Brown Versus Board of Education: Caste, Culture, and the Constitution KF4155 .B758 2003 A Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution by David Nichols E836 .N53 2007 Winning While Losing: Civil Rights, the Conservative Movement, and the Presidency From Nixon to Obama edited by Kenneth Osgood and Derrick White E185.615 .W547 2013 African Americans--Politics and Government Bill Clinton and Black America by DeWayne Wickham E886.2 .W53 2002 Conversations: William Jefferson Clinton from Hope to Harlem by Janis Kearney E886.2 .K43 2006 African Americans--Social Conditions The Mark of Criminality: Rhetoric, Race, and Gangsta Rap in the War-on-crime Era * This is a non-annotated continuation of Allan Metz’s, Bill Clinton: A Bibliography. 1 by Bryan McCann ML3531 .M3 2019 Air Force One (Presidential Aircraft) Air Force One: The Aircraft that Shaped the Modern Presidency by Von Hardesty TL723 .H37 2003 Air Force One: A History of the Presidents and Their Planes by Kenneth Walsh TL723 .W35 -

THE DEMOCRATIC and REPUBLICAN GOVERNORS ASSOCIATIONS and the NATIONALIZATION of AMERICAN PARTY POLITICS Anthony Sparacino Doctor

THE DEMOCRATIC AND REPUBLICAN GOVERNORS ASSOCIATIONS AND THE NATIONALIZATION OF AMERICAN PARTY POLITICS Anthony Sparacino Doctoral Candidate The Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics University of Virginia [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 List of Tables and Figures 4 Introduction: Governors in a Nationalized Party System 5 Chapter 1: A Theory of National Gubernatorial Party Organizations 25 Chapter 2: Governors and National Politics Before the National Gubernatorial Party Organizations 54 Chapter 3: Beyond a Decentralized Party System: Origins of the Republican Governors Association, 1960-1968 91 Chapter 4: The Republican Governors Association in a Nationalizing Party System, 1969-1980 134 Chapter 5: Republican Governors as National Programmatic Partisans, 1981-2000 179 Chapter 6: The Seeds and Stunted Development of the Democratic Governors Conference, 1961- 1980 226 Chapter 7: The Democrats Catch Up: The DGA and the Integration of the Democratic Party, 1981-2000 279 Conclusion: Partisan Governors Associations in a Polarized Era, 2000-Present 325 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible save for a tremendous amount of support, encouragement, and feedback. First, I wish to thank my family. Dad’s interest in politics inspired my own from an early age. Mom always was willing to listen and offer support and encouragement. Both of them provided reassurance in my decision to attend graduate school and were there for me every step of the way. Second, I wish to thank my outstanding dissertation committee. Sidney Milkis, James Ceaser and James Savage have been outstanding, compassionate, and able advisors and have offered more support and inspiration, through their scholarship and personal interactions with me, than I could have ever expected or hoped for. -

Missing White House E-Mails: Mismanagement of Subpoenaed Records

MISSING WHITE HOUSE E-MAILS: MISMANAGEMENT OF SUBPOENAED RECORDS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 23, MARCH 30, MAY 3, AND MAY 4, 2000 Serial No. 106–179 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:14 Jun 14, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\69621.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:14 Jun 14, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\69621.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 MISSING WHITE HOUSE E-MAILS: MISMANAGEMENT OF SUBPOENAED RECORDS VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:14 Jun 14, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\DOCS\69621.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:14 Jun 14, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\DOCS\69621.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 MISSING WHITE HOUSE E-MAILS: MISMANAGEMENT OF SUBPOENAED RECORDS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 23, MARCH 30, MAY 3, AND MAY 4, 2000 Serial No. 106–179 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. -

8/25/08 Roger Simon, Politico's Chief Political Columnist, Has Been a Respected Name in American Journalism Since the 1970S —

8/25/08 Roger Simon, Politico's chief political columnist, has been a respected name in American journalism since the 1970s — and an authoritative voice in American politics for just as long. After the historic contest between Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama finally came to an end in June, Simon launched an intensive effort to get behind the scenes — and to the bottom — of what happened and why. He interviewed scores of well-placed people at all levels of both campaigns, many of whom have been sources of his for years. This project, which Simon named "Relentless" to reflect what he saw as the animating spirit of Obama's remarkable campaign, is the result of Simon's two years of reporting on this campaign, and decades of observing political personalities in action. – John F. Harris Introduction: The path to the nomination By: Roger Simon August 24, 2008 09:09 AM EST In the summer of 2006, Patti Solis Doyle offered David Axelrod a job. Hillary Clinton was running for reelection to the Senate and Solis Doyle was her campaign manager, but everybody knew Clinton was soon going to run for president. And Clinton wanted Axelrod onboard. Axelrod was a highly experienced and successful political consultant and just what Clinton needed. But he declined. Presidential campaigns were mentally taxing, physically exhausting and emotionally draining. There were easier ways to make a buck. Unless. “I wasn’t planning to work in a presidential race,” Axelrod told me, “but if Barack might run, well, he would be the only guy to cause me to get in.” It was not impossible. -

Union Calendar No. 471 105Th Congress, 2D Session –––––––––– House Report 105–829

Union Calendar No. 471 105th Congress, 2d Session ±±±±±±±±±± House Report 105±829 INVESTIGATION OF POLITICAL FUNDRAISING IMPROPRIETIES AND POSSIBLE VIOLATIONS OF LAW INTERIM REPORT SIXTH REPORT BY THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT together with ADDITIONAL AND MINORITY VIEWS Volume 3 of 4 November 5, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed INVESTIGATION OF POLITICAL FUNDRAISING IMPROPRIETIES AND POSSIBLE VIOLATIONS OF LAWÐ VOLUME 3 OF 4 1 Union Calendar No. 471 105th Congress, 2d Session ±±±±±±±±±± House Report 105±829 INVESTIGATION OF POLITICAL FUNDRAISING IMPROPRIETIES AND POSSIBLE VIOLATIONS OF LAW INTERIM REPORT SIXTH REPORT BY THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT together with ADDITIONAL AND MINORITY VIEWS Volume 3 of 4 November 5, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 51±332 WASHINGTON : 1998 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York GARY A. CONDIT, California STEPHEN HORN, California CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana DC MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida ELIJAH E. -

Advisory Entrepreneurship, Fiscal Competence & the Presidency 1977-2009

BANKRUPTING AMERICA: ADVISORY ENTREPRENEURSHIP, FISCAL COMPETENCE & THE PRESIDENCY 1977-2009 by James Clark Gillies B.A., The University of Victoria, 2000 M.A., The University of British Columbia, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2011 James Clark Gillies, 2011 Abstract This study focuses on the presidential advisory system through the lens of fiscal policy in order to develop a better understanding of how modern presidents utilize their advisers and how through a process of advisory entrepreneurship, advisers compete among each other for the president’s attention and time. A set of ideal types of presidential advisers is developed in an effort to shift away from studying the presidency through traditional notions of staff hierarchies and management of the White House to the actual selection of advisers. This research traces fiscal policymaking from the Carter administration through the administration of George W. Bush by using a qualitative case study approach, with elite interviews and a quantitative test of ideal adviser types on fiscal policy, to provide a view of the decision making process inside the White House that often gets submerged in larger institutional studies of Washington. The study also offers an important perspective in explaining how presidents can veer away from fiscal competence. Presidential advisory systems matter a great deal to the policies that get passed through Congress. The fiscal policies themselves are the mark of what presidential advisers often decide is best for the country. -

Final Report Committee on Governmental Affairs

105TH CONGRESS REPT. 105±167 2d Session SENATE Vol. 2 "! INVESTIGATION OF ILLEGAL OR IMPROPER ACTIVITIES IN CONNECTION WITH 1996 FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS FINAL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE TOGETHER WITH ADDITIONAL AND MINORITY VIEWS Volume 2 of 6 MARCH 10, 1998.ÐOrdered to be printed INVESTIGATION OF ILLEGAL OR IMPROPER ACTIVITIES IN CONNECTION WITH 1996 FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNSÐVOLUME 2 1 105TH CONGRESS REPT. 105±167 2d Session SENATE Vol. 2 "! INVESTIGATION OF ILLEGAL OR IMPROPER ACTIVITIES IN CONNECTION WITH 1996 FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS FINAL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE TOGETHER WITH ADDITIONAL AND MINORITY VIEWS Volume 2 of 6 MARCH 10, 1998.ÐOrdered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 47±002 WASHINGTON : 1998 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee, Chairman SUSAN COLLINS, Maine JOHN GLENN, Ohio SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas CARL LEVIN, Michigan PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii DON NICKLES, Oklahoma RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BOB SMITH, New Hampshire MAX CLELAND, Georgia ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HANNAH S. SISTARE, Staff Director and Chief Counsel LEONARD WEISS, Minority Staff Director LYNN L. BAKER, Chief Clerk MAJORITY STAFF MICHAEL J. MADIGAN, Chief Counsel J. MARK TIPPS, Deputy Chief Counsel DONALD T. BUCKLIN, Senior Counsel HAROLD DAMELIN, Senior Counsel HARRY S. MATTICE, Jr., Senior Counsel JOHN H. COBB, Staff Director/Counsel K. LEE BLALACK, Counsel MICHAEL BOPP, Counsel JAMES A. BROWN, Counsel BRIAN CONNELLY, Counsel CHRISTOPHER FORD, Counsel ALLISON HAYWARD, Counsel MATTHEW HERRINGTON, Counsel MARGARET HICKEY, Counsel DAVE KULLY, Counsel JEFFREY KUPFER, Counsel JOHN LOESCH, Counsel WILLIAM ``BILL'' OUTHIER, Counsel GLYNNA PARDE, Counsel PHIL PERRY, Counsel GUS PURYEAR, Counsel MARY KATHRYN (``KATIE'') QUINN, Counsel PAUL ROBINSON, Counsel JOHN S. -

Ambassador Alan D. Solomont

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR ALAN D. SOLOMONT Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: August 30th, 2013 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Boston, MA 1949 BA in Political Science and Urban Studies, Tufts University 1966-1970 “War on Poverty” Student Activism Curriculum Development in Community Organizing Thomas J. Watson Fellowship for Independent Study and Travel 1970-1971 Europe—London, Paris, Copenhagen, Athens, Madrid North Africa Soviet Union—Leningrad Israel Vocations for Social Change—Lowell, MA 1971 Nursing School—Lowell State College Nursing Home Administrator—Prescott House, North Andover, MA 1977 Political Fundraiser 1978-2008 Michael Dukakis 1982 Governor Campaign Michael Dukakis 1988 Presidential Campaign Bill Clinton 1996 Presidential Campaign CEO and Founder, ADS Group 1985-1995 Owned and managed nursing homes, rehab facilities, assisted living facilities, senior houses, and homecare Democratic National Committee 1992-2008 Chairman of the Business Leadership Forum 1996-1997 National Level Fundraiser for the Democratic Party 1997-1998 President of the Nursing Home Association, MA 1997 1 Corporation for National and Community Service 2000- Member of Board of Directors 2000-2009 Appointed by Bill Clinton Reappointed by George W. Bush Elected Chairman of the Board 2009 Barack Obama Presidential Campaign 2007-2008 Fundraising Organizer for New England—New England Steering Committee for Obama Appointed into the Foreign Service by Barack Obama 2009 Ambassador to Spain and Andorra 2009-2013 Unequal perceptions of US-Spain relations Guantanamo Detainees Four Pillars Framework to guide the embassy Building a positive relationship with the press Rebuilding after the economic crisis “Ripening of Globalization” Freedom and Bureaucracy US-EU Summit Economics and business in Spain Spreading American values Lack of support for Foreign Service spouses INTERVIEW Q: Today is August 30th, 2013. -

The Phony Left That Helped Create Obama Obama Maternal

Obama_Barack_and_Michelle_gay_blackmail_Rezko NewsFollowup.com Franklin Scandal Omaha search archives sitemap home Obama maternal grandparents and the OSS / CIA and CIA Asia below. The Phony Left that helped create and below chart From questionsquestions.net Obama NFU MOST ACTIVE PA Go to Alphabetic list Academic Freedom Conference Obama Death List Rothschild Timeline Bush / Clinton Body Count Got to Obama body count, White House battles U.S. =go to NFU pages death list page intelligence factions via WikiLeaks and Anonymous Back to Obama home page below related topics related topics related topics Arms Proliferation Afghanistan De-regulation Bush Watch. Iraq Taxes Environment Iran War Nonviolence Saudi Arabia Zionism Protest Obama, groomed for 30 years by Ford Foundation - Trilateral Commission to become president, family has long history with CIA....bisexual, Blackmail, top go to WMR report CIA, Trilateral Commission, Ford Foundation groomed Obama for 30 years to become President. PROGRESSIVE REFERENCE CONSERVATIVE* Ann Dunham, developed microfinance programs 1313 gang, Spellman Fund helped set it up, social under Peter Geithner, father of Tim Geithner, more engineering in favor of financier interests, totalitarian A-W-I-P Obama's CIA Pedigree, WMR reprint Summary, control, from the vision of Charles E. Merriam, and Ayers, William Ayers Obama, Gay -- Fitzgerald Louis Brownlow, nerve center of American public BlackListedNews son For an official-esque, sanitized administration, played key roles in creating UN, http://www.newsfollowup.com/obama_phony_left_cia_ford_foundation_trilateral_soros.htm[5/28/2014 -

George Soros, a Key Donor Who Pledged $10 Million in Soft Money to ACT As

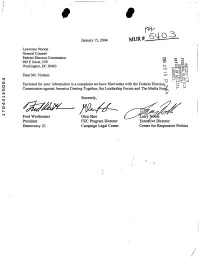

-- I .. I 8 I January 15, ‘2004 Lawrence Norton General Counsel Federal Election Commission ul-d ca 999 E Street, NW J=- Washington, DC 20463 Dear Mr. Norton:. 9 Enclosed for your information is a complaint we have filed today with the Federal Election r.3 Commission against America Coming Together, the Leadership Forum and The Media Fur$, c Sincerely, Fred Wertheimer Glen Shor President FEC Program Director Democracy 21 Campaign Legal Center Center for Responsive Politics / I BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Democracy 21 1825 I Street, NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20006 202-429-2008 % :. .. Campaign Legal Center . A- d 1101 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 330 cn .Washington,DC 20036 202-736-2200 Center for Responsive Politics 1101 14'" Street, NW, Suite 1030 . Washington, DC 20005 202-857-0044 V. America Coming Together 888 16th Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 202-974-8360 The Leadership Forum 4123 South 36thStreet Arlington, Virginia 22206 \ The Media Fund 1120 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20036 202-974-8320 COMPLAINT 2 1. In March, 2002, Congress enacted the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) in order to stop the injection of soft money into federal elections. The relevant provisions of BCRA were upheld by the Supreme Court in McConneZZ v. FEC,540 U.S. (slip op. December 10,2003). 2. Since the enactment of BCRA, a number of party and political operatives, and former soft money donors, have been engaged in efforts to circumvent BCRA by planning and implementing new schemes to use soft money to influence the 2004 presidential and congressional elections. -

BCRA and the 527 Groups

BCRA and the 527 Groups Steve Weissman and Ruth Hassan Campaign Finance Institute February 9, 2005 Revised March 8, 2005 DRAFT CHAPTER For publication in The Election after Reform: Money, Politics and the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. Michael J. Malbin, ed., (Rowman and Littlefield, forthcoming) DRAFT CHAPTER Introduction In the wake of the 2004 election, press commentary suggested that rising “527 groups” had undermined the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act’s ban on unlimited corporate, union and individual contributions to political parties and candidates. According to the National Journal, backers of the new law who had “sought to tamp down dire warnings” that close to $500 million in banned soft money “would simply migrate from the parties to 527 organizations” were now “singing a different tune”(Carney 2004). A New York Times editorial lamented that “No sooner had the [campaign finance reform] bill become law than party financiers found a loophole and created groups known as 527s, after the tax-code section that regulated them”(Editorial 2004). The Federal Election Commission (FEC) had refused to subject 527s to contribution restrictions so long as their stirring campaign ads and voter mobilization programs steered clear of formal candidate endorsements such as “Vote for” and “Vote Against.” The result, reported the Washington Post, was a new pattern of soft money giving, with “corporate chieftains and companies such as Microsoft, Boeing and General Electric” displaced as “key contributors” by “two dozen superwealthy and largely unknown men and women… each giving more than $1 million”(Grimaldi 2004). Billionaire George Soros would top the list at $24 million. -

Attachm.Ent.;A *

I .. ...... - ... ..... .... .. .. ..... .... .. ... .. ' ... .......... ........ '. .........,. .... ............... .. ,.. .. .. ... ............ .. .. ........ ... .! . ..... .. ....... I ,: ................ ... ... ...... ...... .. ...I. .. .. .. .... ............. ......... , .' : ............... : :._. .... .. ........ '..I .., I ... ' .' . .' .. ...... oq ............... .. .,.; .. '_ ... ... ,. , :., ' . ......... y ..... ... ..a4 '. , ' . ... .! ............. ... ...... .. .... &'. ... ... ,. ... ,P . ,.,Attachm.ent.;A *. .. :i+.. ... ......'.. .., .... _. ........ .. ' .. .. .. .... ..: ..... .. Statement of Senator John McCain, Senate Committee on Rules I Wednesday, March IO, 2004 In its recent opinion in Mcconnell v. FEC, the Supreme Court wisely noted that money, like water, is going to seek a way’toleak back into the system. .We already see that. Now that -the-.. .. -. -. .... parties have been taken out of the soft money business, there are efforts by political operators.to redirect some of that money to groups that operate as political organizations under Section 527 of the IRS Code, or so-called “Section 527” groups. The game is the same: these groups are raising huge corporate and union contributions, and .I multi-million dollar donations from wealthy individuals, and want to spend that money on so- , called “issue” ads that promote or attack federal candidates, and voter mobilization efforts , intended to influence federal elections. The tax laws say’that a 527 group is a “poiitical organization” that is organized and