Section 5.4 Human Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX 4-A Stakeholder and Aboriginal Organizations Record Of

S TAR-ORION S OUTH D IAMOND P ROJECT E NVIRONMENTAL I MPACT A SSESSMENT APPENDIX 4-A Stakeholder and Aboriginal Organizations Record of Contacts SX03733 – Section 4.0 Table 4-A.1 RECORDS OF CONTACT: GOVERNMENT CONTACTS (November 1, 2008 – November 30, 2010) Event Type Event Date Stakeholders Team Members Details Phone Call 19-Nov-08 Town of Choiceland, DDAC Julia Ewing Call to JE to tell her that the SUMA conference was going on at the exact same time as Shores proposed open houses and 90% of elected leadership would be away attending the conference in Saskatoon. Meeting 9-Dec-08 Economic Development Manager, City of Eric Cline; Julia Ewing Meeting at City Hall in Prince Albert. Prince Albert; Economic Development Coordinator, City of Prince Albert Meeting 11-Dec-08 Canadian Environmental Assessment Eric Cline; Julia Ewing; Meeting at Shore Gold Offices - Agency Ethan Richardson Review community engagement and Development Project Administrator, Ministry other EIA approaches with CEA and of Environment; MOE Director, Ministry of Environment; Senior Operational Officer, Natural Resources Canada; Environmental Project Officer, Ministry of Environment Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Acting Deputy Minister, Energy and Julia Ewing Invitation to Open House Resources, Government of Saskatchewan Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Deputy Minister, First Nations Métis Eric Cline Invitation to Open Houses Relations, Government of Saskatchewan Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Executive Director, First Nations Métis Eric Cline Invitation to Open Houses Relations Government of Saskatchewan Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Senior Consultation Advisor, Aboriginal Eric Cline Invitation to Open Houses Consultation, First Nations Métis Relations Government of Saskatchewan Phone Call 21-Jan-09 Canadian Environmental Assessment Eric Cline; Julia Ewing; Discuss with Feds and Prov, Shore's Agency; Ethan Richardson; Terri involvement in the consultation Development Project Administrator, Ministry Uhrich process for the EIA. -

Event151-2Cd20427.Pdf (James Smith Cree Nation.Pdf)

INDIAN CLAIMS COMMISSION JAMES SMITH CREE NATION IR 100A INQUIRY PANEL Chief Commissioner Renée Dupuis Commissioner Alan C. Holman COUNSEL For the James Smith Cree Nation William A. Selnes For the Government of Canada Robert Winogron/Uzma Ihsanullah To the Indian Claims Commission Kathleen N. Lickers March 2005 CONTENTS SUMMARY vii KEY HISTORICAL NAMES CITED ix TERMINOLOGY xiii PREFACE xvii PART I INTRODUCTION 1 MANDATE OF THE COMMISSION 3 PART II HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 7 CLAIMANTS’ ADHESIONS TO TREATY 5 AND 67 Geography and Claimants 7 Cumberland Band Adhesion to Treaty 5, 1876 7 James Smith Band and the Signing of Treaty 6, 1876 9 Cumberland Band Requests Reserve at Fort à la Corne 10 Survey of IR 20 at Cumberland Lake in Treaty 5 16 CONDITIONS AT FORT À LA CORNE, 1883–92 20 Creation of the Pas Agency in Treaty 5, 1883 20 Department Permits Move to Fort à la Corne, 1883 20 Movement from Cumberland to Fort à la Corne, 1883–86 21 Setting Aside Land for IR 100A, 1883–85 25 The North-West Rebellion and the Cumberland Band 30 Scrip Offered at Cumberland 31 Paylist for Cumberland Band at Fort à la Corne, 1886 33 Other Treaty 5 Bands at Fort à la Corne 33 Survey of IR 100A, 1887 34 Department Support for Agriculture at Fort à la Corne 35 Cumberland Band Movement, 1887–91 37 Return to the Cumberland District, 1886–91 38 Leadership of Cumberland Band at Fort à la Corne, 1886–92 39 Request for Separate Leadership at IR 100A, 1888 40 BAND MEMBERSHIP 41 Department Practice for Transfers of Band Membership 41 Settlement of Chakastaypasin Band Members -

CN Vignettes

Updated 06/27/08 Rev.A www.canadianrailwayobservations.com NOTICE TO OUR READERS: CRO is currently seeking a volunteer French - English translator to assist our Co-Editor Samuel Thibodeau about 5 hours per month with OFC ... (the French version of CRO). If interested, please contact: [email protected] for more information. AVIS À TOUS LES LECTEURS: CRO est présentement à la recherche d'un traducteur bénévole pour assister Samuel Thibodeau (co-éditeur responsable de OFC, la version française de CRO). Cette personne bilingue doit être disponible pour travailler environ 5 heures par mois. Le travail s'effectue à domicile via Internet. Contactez [email protected] pour de plus amples renseignements. CANADIAN NATIONAL CN Locomotives retired since last issue: CN SD50F’s 5407, 5417, 5424, and 5450, on May 13th CN SD50F 5437 on May 15th DMIR SD38 205 on May 23rd CN SD50F’s 5405, 5443, 5454 on May 25th CN SD50F’s 5440, 5445, 5458 on May 28th DMIR SD38 201 on May 29th CN SD50F’s 5439 and 5451 on June 17th DMIR SD9m 316 on June 17th. As can be seen above, in June, CN began placing more GMDD-built 5400-series SD50F`s into storage at Woodcrest and Memphis, TN. At press time, 20 CN SD50F’s (or 1/3 of the fleet), had already been retired out of a total of 60 units. The full bodied 5400-class, are now on the hit list for retirement when one suffers a major failure. Current economic conditions have in part lead to these being retired before their time. -

James Smith Cree Nation During the Following Times When the Individual Was Likely Infectious

Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority Inc. PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT: Potential COVID-19 Exposure in Mass Gatherings Sunday, November 8th, 2020 1600HRS Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority (NITHA) public health officials are notifying the public that an individual who tested COVID-19 positive attended wake/funeral events in James Smith Cree Nation during the following times when the individual was likely infectious: • Wake Service, Monday, November 2, 2020 • Funeral Service, Tuesday, November 3, 2020 Public health officials are advising individuals who were at the event during the specified dates and times listed above to immediately self-isolate if they have had or currently have symptoms of COVID-19 and to call HealthLine 811 or their community health clinic to arrange for assessment and testing. All other individuals who are not experiencing symptoms should self-monitor for 14 days from the date of last exposure. It is important to note that individuals may develop symptoms from two to 14 days following exposure to the virus that causes COVID-19. Symptoms of COVID-19 can vary from person to person. Symptoms may also vary in different age groups. Some of the more commonly reported symptoms include: • new or worsening cough • shortness of breath or difficulty breathing • temperature equal to or over 38°C • feeling feverish • chills • fatigue or weakness • muscle or body aches • new loss of smell or taste • headache • gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting) • feeling very unwell For more information on self-monitoring and self-isolation, visit saskatchewan.ca/COVID19 -30- Media Relations [email protected] (306) 953-5000 Mailing Address: Box #787, 2300 – 10th Avenue West, PBCN OffiCe Complex- Main Floor Chief JosepH Custer Reserve #201 – PrinCe Albert, SK S6V 6Z1, Canada Telephone: (306) 953-5000 Fax: (306) 953-5010 . -

Firefighters Respond to Nursing Home

$150 PER COPY (GST included) www.heraldsun.ca Publications Mail Agreement No. 40006725 -YPKH`-LIY\HY` Serving Whitewood, Grenfell, Broadview and surrounding areas • Publishing since 1893 =VS0ZZ\L 1XUVLQJKRPHÀUHFDOO ELAINE ASHFIELD | GRASSLANDS NEWS 7KH:KLWHZRRG)LUH'HSDUWPHQWZDVGLVSDWFKHGWRWKH:KLWHZRRG&RPPXQLW\+HDOWK&HQWUHRQ7XHVGD\DIWHUWKHÀUHDODUPDQGDVSULQNOHUZHUHDFWLYDWHG LQVLGHWKHODXQGU\URRPRIWKHORQJWHUPFDUHIDFLOLW\)LUHÀJKWHUVDQGPDLQWHQDQFHSHUVRQQHOZHUHDEOHWRHYHQWXDOO\ORFDWHWKHRULJLQRIWKHSUREOHPDVSULQ- NOHULQVLGHWKHFHLOLQJWKDWKDGIUR]HQFDXVLQJWKHDFWLYDWLRQRIWKHVSULQNOHURQWROLJKWVDQGZLULQJ Firefighters respond to nursing home Frozen pipe sets off ceiling sprinkler and fire alarm in long term care facility By Chris Ashfield to transport residents if necessary as well as be pre- Grasslands News pared for lodging if required. Fortunately, no residents had to be evacuated from the facility. Fire chief Bernard Brûlé said calls like these are Whitewood Fire Department (WFD) was called to always of great concern, especially at this time of year the Whitewood Community Health Centre on Tuesday with temperatures so cold. morning to respond to a possible fire in the long-term “Our first priority is always the safety of the resi- care facility. dents and having the necessary resources in place to The call came in on Feb. 9 at about 10:15 a.m. after evacuate them if necessary, especially on such a cold a sprinkler in the laundry room went off along with day. Fortunately in this situation, it did not get to that the facilities fire alarm system. There was -

SPATIAL DIFFUSION of ECONOMIC IMPACTS of INTEGRATED ETHANOL-CATTLE PRODUCTION COMPLEX in SASKATCHEWAN a Thesis Submitted To

SPATIAL DIFFUSION OF ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF INTEGRATED ETHANOL-CATTLE PRODUCTION COMPLEX IN SASKATCHEWAN A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Agricultural Economics University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Emmanuel Chibanda Musaba O Copyright Emmanuel C. Musaba, 1996. All rights reserved. National Library Bibliotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Sewices services bibliographiques 395 WeIIington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your& vobrs ref6llBIlt8 Our & NomMhwm The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde me licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter' distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelf2m, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celIe-ci ne doivent Stre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial ilfihent b of the requirements for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY EMMANUEL CHLBANDA MUSABA Department of AgricuIturd Economics CoUege of Agriculture University of Saskatchewan Examining Committee: Dr. -

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Proceedings of a Conference Held January 27-29, 1998, in Edmonton, Alberta

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Proceedings of a conference held January 27-29, 1998, in Edmonton, Alberta Conference sponsored by the First Nation Forestry Program, a ioint initiative of Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, and Indian and Northern AHairs Canada published by Canadian Forest Service Northern Forestry Centre, Edmonton 1998 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 1998 This publication is available at no charge from: Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Northern Forestry Centre 5320 - 122 Street Edmonton, Alberta T6H 3S5 A microfiche edition of this publication may be purchased from: Micromedia Ltd. Suite 305 240 Catherine Street Ottawa, Ontario K2P 2G8 Page ii Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Conforence,Ja nuary27-29, 1998 Contents Foreword ......................................... ...........................v Joe De Franceschi, Conference Coordinator, Canadian Forest Service, Alberta Pre-conference Workshop: Where Does My Proiect Fit? Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Bruce We ndel, Business Development Bank of Canada, Alberta ...............................2 CESO Celebrates Thirty Years of Service to the Wo rld George F. Ferrand, Regional Manager, Albertaand Western Arctic, CESO, Alberta .................4 Aid from Peace Hills Tr ust Harold Baram, Peace Hills Trust, Alberta ................................................8 Aboriginal Business Canada Lloyd Bisson, Aboriginal Business Canada, Alberta .........................................9 Session 1. The First Nation Forestry -

Brief Submitted to the Committee

Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs Sixth Floor, 131 Queen Street House of Commons Ottawa ON K1A 0A6 Canada November 27, 2020 Please accept this brief for the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs study of support for Indigenous communities, businesses, and individuals through a second wave of Covid-19. SITUATION Since March 2020, James Smith Cree Nation (JSCN) and the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN), have made requests to Canada for funding support for a First Nations led and managed solution to address our urgent and emergency need for Personal Protective Equipment in order to ensure the safety and wellbeing of our communities in the face of COVID-19. We have engaged exhaustive correspondence and communications about these proposals with: Rt. Hon. Justin Trudeau, Hon. Chrystia Freeland, Hon. Marc Miller, Mr. Mike Burton, Hon. Carolyn Bennett, and ISC Regional officials Jocelyn Andrews, Rob Harvey and Bonnie Rushowick. Despite extensive consultations and discussions with the department and minister’s office, we have experienced significant delays and denials from Canada to support these urgently needed and emergency proposals. This has been well documented since May, with particular reference to ‘Indigenous Services Moving Goalposts on First Nations PPE’, CBC News, September 11, 2020 (https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/first-nations-ppe-proposal-1.5721249). The failed funding and departmental dysfunction have resulted in significant outbreaks which are occurring across our regions. By Canada’s own admission on November 29, COVID-19 is now four times (4x) worse in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities than during the first wave which occurred from March through May 2020. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

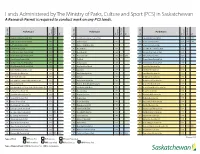

In Saskatchewan

Lands Administered by The Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport (PCS) in Saskatchewan A Research Permit is required to conduct work on any PCS lands. Park Name Park Name Park Name Type of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year HP Cannington Manor Provincial Park 1986 NE Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park 1973 RP Crooked Lake Provincial Park 1986 PAA 2018 HP Cumberland House Provincial Park 1986 PR Anderson Island 1975 RP Danielson Provincial Park 1971 PAA 2018 HP Fort Carlton Provincial Park 1986 PR Bakken - Wright Bison Drive 1974 RP Echo Valley Provincial Park 1960 HP Fort Pitt Provincial Park 1986 PR Besant Midden 1974 RP Great Blue Heron Provincial Park 2013 HP Last Mountain House Provincial Park 1986 PR Brockelbank Hill 1992 RP Katepwa Point Provincial Park 1931 HP St. Victor Petroglyphs Provincial Park 1986 PR Christopher Lake 2000 PAA 2018 RP Pike Lake Provincial Park 1960 HP Steele Narrows Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Black 1974 RP Rowan’s Ravine Provincial Park 1960 HP Touchwood Hills Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Livingstone 1986 RP The Battlefords Provincial Park 1960 HP Wood Mountain Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Glen Ewen Burial Mound 1974 RS Amisk Lake Recreation Site 1986 HS Buffalo Rubbing Stone Historic Site 1986 PR Grasslands 1994 RS Arm River Recreation Site 1966 HS Chimney Coulee Historic Site 1986 PR Gray Archaeological Site 1986 RS Armit River Recreation Site 1986 HS Fort Pelly #1 Historic Site 1986 PR Gull Lake 1974 RS Beatty -

Directory of Cultural Services

Directory of Cultural Services For Prince Albert The Chronic Disease Network & Access Program Prince Albert Grand Council www.ehealth-north.sk.ca FREQUENTLY CALLED NUMBERS Emergency police, fire and ambulance: Ph: 911 Health Line 24 hour, free confidential health advice. Ph: 1-877-800-0002 Prince Albert City Police Victim’s Services Assist victims of crime, advocacy in the justice system for victims and counseling referrals. Ph: (306) 953-4357 Mobile Crisis Unit 24 hour crisis intervention and sexual assault program. Ph: (306) 764-1011 Victoria Hospital Emergency Health Care Ph: (306) 765-6000 Saskatchewan Health Cards Ph: 1-800-573-7377 MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES Prince Albert Mental Health Centre Inpatient and outpatient services. Free counseling with Saskatchewan Health Card Ph: (306) 765-6055 Canadian Mental Health Association Information about mental health issues. Ph: (306) 763-7747 The Nest (Drop in) 1322 Central Avenue (upstairs) Prince Albert, SK Hours: Mon – Fri, 8:30 – 3:30 PM Ph: (306) 763-8843 CULTURAL PROGRAMS Bernice Sayese Centre 1350 – 15th Avenue West Prince Albert, SK Services include nurse practitioner, seniors health, sexual health and addictions. Cultural programs include Leaving a Legacy (Youth Program); cultural programs in schools, recreation, karate, tipi teachings, pipe ceremonies and sweats. Hours: 9:00 – 9:00 PM Ph: (306) 763-9378 Prince Albert Indian and Métis Friendship Centre 1409 1st Avenue East Prince Albert, SK Services include a family worker, family wellness and cultural programs. Ph: (306) 764-3431 Holistic Wellness Centre Prince Albert Grand Council P.O. Box 2350 Prince Albert, SK Services include Resolution Health Support Workers and Elder services available upon request. -

The Drought Relief (Herd Retention) Program Regulations

1 DROUGHT RELIEF (HERD RETENTION) PROGRAM F-8.001 REG 21 The Drought Relief (Herd Retention) Program Regulations Repealed by Saskatchewan Regulations 26/2010 (effective April 1, 2010) Formerly Chapter F-8.001 Reg 21 (effective August 14, 2002) as amended by Saskatchewan Regulations 105/2002, 118/2002, 10/2003 and 38/2003. NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 DROUGHT RELIEF F-8.001 REG 21 (HERD RETENTION) PROGRAM Table of Contents 1 Title 2 Interpretation 3 Drought relief (herd retention) program established 4 Application for payment 5 Time limit for submitting applications 6 Approval of application 7 Calculation of drought relief payment 8 Conditions of program 9 Reconsideration 10 Overpayment 11 Coming into force Appendix Table 1 Animal Unit Equivalents Table 2 Drought Regions 3 DROUGHT RELIEF (HERD RETENTION) PROGRAM F-8.001 REG 21 CHAPTER F-8.001 REG 21 The Farm Financial Stability Act Title 1 These regulations may be cited as The Drought Relief (Herd Retention) Program Regulations. Interpretation 2 In these regulations: (a) “animal unit equivalent” means the animal unit equivalent assigned to a species of livestock, as set out in Table 1 of the Appendix; (b) “applicant” means a livestock producer