Getting Started with Use Case Modeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07 Requirements What About RFP/RFB/Rfis?

CMPSCI520/620 07 Requirements & UML Intro 07 Requirements SW Requirements Specification • Readings • How do we communicate the Requirements to others? • [cK99] Cris Kobryn, Co-Chair, “Introduction to UML: Structural and Use Case Modeling,” UML Revision Task Force Object Modeling with OMG UML Tutorial • It is common practice to capture them in an SRS Series © 1999-2001 OMG and Contributors: Crossmeta, EDS, IBM, Enea Data, • But an SRS doesn’t need to be a single paper document Hewlett-Packard, IntelliCorp, Kabira Technologies, Klasse Objecten, Rational Software, Telelogic, Unisys http://www.omg.org/technology/uml/uml_tutorial.htm • Purpose • [OSBB99] Gunnar Övergaard, Bran Selic, Conrad Bock and Morgan Björkande, “Behavioral Modeling,” UML Revision Task Force, Object Modeling with OMG UML • Contractual requirements Tutorial Series © 1999-2001 OMG and Contributors: Crossmeta, EDS, IBM, Enea elicitation Data, Hewlett-Packard, IntelliCorp, Kabira Technologies, Klasse Objecten, Rational • Baseline Software, Telelogic, Unisys http://www.omg.org/technology/uml/uml_tutorial.htm • for evaluating subsequent products • [laM01] Maciaszek, L.A. (2001): Requirements Analysis and System Design. • for change control requirements Developing Information Systems with UML, Addison Wesley Copyright © 2000 by analysis Addison Wesley • Audience • [cB04] Bock, Conrad, Advanced Analysis and Design with UML • Users, Purchasers requirements http://www.kabira.com/bock/ specification • [rM02] Miller, Randy, “Practical UML: A hands-on introduction for developers,” -

Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: a Phenomenological Study of Acting

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2019 Blurred Lines Between Role and Reality: A Phenomenological Study of Acting Gregory Hyppolyte Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Psychology Commons BLURRED LINES BETWEEN ROLE AND REALITY: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF ACTING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY In CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY by GREGORY HIPPOLYTE BROWN August 2019 This dissertation, by Gregory Hippolyte Brown, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Chairperson __________________________ Sharleen O‘ Brien, Ph.D. Second Faculty __________________________ Thalia R. Goldstein, Ph.D. External Expert ii Copyright © 2019 Gregory Hippolyte Brown iii Abstract When an actor plays a character in a film, they try to connect with the emotions and behavioral patterns of the scripted character. There is an absence of literature regarding how a role influences an actor’s life before, during, and after film production. This study examined how acting roles might influence an actor during times on set shooting a movie or television series as well as their personal life after the filming is finished. Additionally the study considered the psychological impact of embodying a role, and whether or not an actor ever has the feeling that the performed character has independent agency over the actor. -

Writing and Reviewing Use-Case Descriptions

Bittner/Spence_06.fm Page 145 Tuesday, July 30, 2002 12:04 PM PART II WRITING AND REVIEWING USE-CASE DESCRIPTIONS Part I, Getting Started with Use-Case Modeling, introduced the basic con- cepts of use-case modeling, including defining the basic concepts and understanding how to use these concepts to define the vision, find actors and use cases, and to define the basic concepts the system will use. If we go no further, we have an overview of what the system will do, an under- standing of the stakeholders of the system, and an understanding of the ways the system provides value to those stakeholders. What we do not have, if we stop at this point, is an understanding of exactly what the system does. In short, we lack the details needed to actually develop and test the system. Some people, having only come this far, wonder what use-case model- ing is all about and question its value. If one only comes this far with use- case modeling, we are forced to agree; the real value of use-case modeling comes from the descriptions of the interactions of the actors and the system, and from the descriptions of what the system does in response to the actions of the actors. Surprisingly, and disappointingly, many teams stop after developing little more than simple outlines for their use cases and consider themselves done. These same teams encounter problems because their use cases are vague and lack detail, so they blame the use-case approach for having let them down. The failing in these cases is not with the approach, but with its application. -

Lecture for Chapter 2, Modeling With

09/10/2019 Overview: modeling with UML Modeling with UML What is modeling? What is UML? Use case diagrams Class diagrams Oriented Software Engineering - Object What is modeling? Example: street map Modeling consists of building an abstraction of reality. Abstractions are simplifications because: They ignore irrelevant details and They only represent the relevant details. What is relevant or irrelevant depends on the purpose of the model. Why model software? Systems, Models and Views Why model software? A model is an abstraction describing a subset of a system A view depicts selected aspects of a model Software is getting increasingly more complex A notation is a set of graphical or textual rules for depicting views Windows XP > 40 million lines of code Views and models of a single system may overlap each other A single programmer cannot manage this amount of code in its entirety. Code is not easily understandable by developers who did not Examples: write it System: Aircraft We need simpler representations for complex systems Models: Flight simulator, scale model Modeling is a mean for dealing with complexity Views: All blueprints, electrical wiring, fuel system 1 09/10/2019 Systems, Models and Views Models, Views and Systems (UML) Flightsimulator Blueprints * * System Model View Aircraft Described by Depicted by Model 2 View 2 View 1 System Airplane: System View 3 Model 1 Scale Model: Model Flight Simulator: Model Electrical Wiring Scale Model Blueprints: View Fuel System: View Electrical Wiring: View What is UML? What is UML? UML (Unified Modeling Language) The Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a language for Specifying An emerging standard for modeling object-oriented software. -

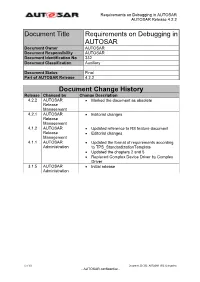

Document Title Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR

Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Document Title Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 332 Document Classification Auxiliary Document Status Final Part of AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Document Change History Release Changed by Change Description 4.2.2 AUTOSAR Marked the document as obsolete Release Management 4.2.1 AUTOSAR Editorial changes Release Management 4.1.2 AUTOSAR Updated reference to RS feature document Release Editorial changes Management 4.1.1 AUTOSAR Updated the format of requirements according Administration to TPS_StandardizationTemplate Updated the chapters 2 and 5 Replaced Complex Device Driver by Complex Driver 3.1.5 AUTOSAR Initial release Administration 1 of 19 Document ID 332: AUTOSAR_SRS_Debugging - AUTOSAR confidential - Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Disclaimer This specification and the material contained in it, as released by AUTOSAR, is for the purpose of information only. AUTOSAR and the companies that have contributed to it shall not be liable for any use of the specification. The material contained in this specification is protected by copyright and other types of Intellectual Property Rights. The commercial exploitation of the material contained in this specification requires a license to such Intellectual Property Rights. This specification may be utilized or reproduced without any modification, in any form or by any means, for informational purposes only. For any other purpose, no part of the specification may be utilized or reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. The AUTOSAR specifications have been developed for automotive applications only. -

The Guide to Succeeding with Use Cases

USE-CASE 2.0 The Guide to Succeeding with Use Cases Ivar Jacobson Ian Spence Kurt Bittner December 2011 USE-CASE 2.0 The Definitive Guide About this Guide 3 How to read this Guide 3 What is Use-Case 2.0? 4 First Principles 5 Principle 1: Keep it simple by telling stories 5 Principle 2: Understand the big picture 5 Principle 3: Focus on value 7 Principle 4: Build the system in slices 8 Principle 5: Deliver the system in increments 10 Principle 6: Adapt to meet the team’s needs 11 Use-Case 2.0 Content 13 Things to Work With 13 Work Products 18 Things to do 23 Using Use-Case 2.0 30 Use-Case 2.0: Applicable for all types of system 30 Use-Case 2.0: Handling all types of requirement 31 Use-Case 2.0: Applicable for all development approaches 31 Use-Case 2.0: Scaling to meet your needs – scaling in, scaling out and scaling up 39 Conclusion 40 Appendix 1: Work Products 41 Supporting Information 42 Test Case 44 Use-Case Model 46 Use-Case Narrative 47 Use-Case Realization 49 Glossary of Terms 51 Acknowledgements 52 General 52 People 52 Bibliography 53 About the Authors 54 USE-CASE 2.0 The Definitive Guide Page 2 © 2005-2011 IvAr JacobSon InternationAl SA. All rights reserved. About this Guide This guide describes how to apply use cases in an agile and scalable fashion. It builds on the current state of the art to present an evolution of the use-case technique that we call Use-Case 2.0. -

INCOSE: the FAR Approach “Functional Analysis/Allocation and Requirements Flowdown Using Use Case Realizations”

in Proceedings of the 16th Intern. Symposium of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE'06), Orlando, FL, USA, Jul 2006. The FAR Approach – Functional Analysis/Allocation and Requirements Flowdown Using Use Case Realizations Magnus Eriksson1,2, Kjell Borg1, Jürgen Börstler2 1BAE Systems Hägglunds AB 2Umeå University SE-891 82 Örnsköldsvik SE-901 87 Umeå Sweden Sweden {magnus.eriksson, kjell.borg}@baesystems.se {magnuse, jubo}@cs.umu.se Copyright © 2006 by Magnus Eriksson, Kjell Borg and Jürgen Börstler. Published and used by INCOSE with permission. Abstract. This paper describes a use case driven approach for functional analysis/allocation and requirements flowdown. The approach utilizes use cases and use case realizations for functional architecture modeling, which in turn form the basis for design synthesis and requirements flowdown. We refer to this approach as the FAR (Functional Architecture by use case Realizations) approach. The FAR approach is currently applied in several large-scale defense projects within BAE Systems Hägglunds AB and the experience so far is quite positive. The approach is illustrated throughout the paper using the well known Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) example. INTRODUCTION Organizations developing software intensive defense systems, for example vehicles, are today faced with a number of challenges. These challenges are related to the characteristics of both the market place and the system domain. • Systems are growing ever more complex, consisting of tightly integrated mechanical, electrical/electronic and software components. • Systems have very long life spans, typically 30 years or longer. • Due to reduced acquisition budgets, these systems are often developed in relatively short series; ranging from only a few to several hundred units. -

Sysml, the Language of MBSE Paul White

Welcome to SysML, the Language of MBSE Paul White October 8, 2019 Brief Introduction About Myself • Work Experience • 2015 – Present: KIHOMAC / BAE – Layton, Utah • 2011 – 2015: Astronautics Corporation of America – Milwaukee, Wisconsin • 2001 – 2011: L-3 Communications – Greenville, Texas • 2000 – 2001: Hynix – Eugene, Oregon • 1999 – 2000: Raytheon – Greenville, Texas • Education • 2019: OMG OCSMP Model Builder—Fundamental Certification • 2011: Graduate Certification in Systems Engineering and Architecting – Stevens Institute of Technology • 1999 – 2004: M.S. Computer Science – Texas A&M University at Commerce • 1993 – 1998: B.S. Computer Science – Texas A&M University • INCOSE • Chapters: Wasatch (2015 – Present), Chicagoland (2011 – 2015), North Texas (2007 – 2011) • Conferences: WSRC (2018), GLRCs (2012-2017) • CSEP: (2017 – Present) • 2019 INCOSE Outstanding Service Award • 2019 INCOSE Wasatch -- Most Improved Chapter Award & Gold Circle Award • Utah Engineers Council (UEC) • 2019 & 2018 Engineer of the Year (INCOSE) for Utah Engineers Council (UEC) • Vice Chair • Family • Married 14 years • Three daughters (1, 12, & 10) 2 Introduction 3 Our Topics • Definitions and Expectations • SysML Overview • Basic Features of SysML • Modeling Tools and Techniques • Next Steps 4 What is Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE)? Model-based systems engineering (MBSE) is “the formalized application of modeling to support system requirements, design, analysis, verification and validation activities beginning in the conceptual design phase and continuing throughout development and later life cycle phases.” -- INCOSE SE Vision 2020 5 What is Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE)? “Formal systems modeling is standard practice for specifying, analyzing, designing, and verifying systems, and is fully integrated with other engineering models. System models are adapted to the application domain, and include a broad spectrum of models for representing all aspects of systems. -

How to Build a UML Model Announcements Rational Unified

Announcements How to build a UML model ❚ HW3 – Phase 1 due on Feb 6th, 5:00pm (need to create new pairs, accounts) ❚ Feedback on M2: turn procedural code RUP into OO code, Planning game (show tables Steriotypes, packages, and with features, subtasks, estimates, object diagrams actuals, pair-programming partners) Case study ❚ Register for the Feb 18 Industry Reception 1 CS361 7-2 Rational Unified Process How RUP builds a model ❚ Designed to work with UML ❚ Gather use cases from customer ❚ No longer being promoted by IBM ❚ Make initial object model ❚ Roles - (out of 20 or so) ❚ For each use case: ❙ Architect ❙ step through use case, ❙ UI designer ❙ note the objects it requires ❙ Use case specifier ❙ note the operations it uses ❙ Use case engineer ❙ Component engineer ❚ Clean up the model CS361 7-3 CS361 7-4 Architect UI design ❚ Determine which use cases need to be ❚ Logical design developed first. ❙ Which user-interface elements are needed for ❚ High priority use cases each use case? ❙ describe important and critical functionality ❙ What information does the actor need to receive from or give to the system? ❘ security ❘ database ❚ Prototyping ❙ hard to retrofit later ❙ Often is on paper. ❙ Test on real users CS361 7-5 CS361 7-6 1 Requirements Specification Analysis model ❚ Not all requirements go in a use case. ❚ Class diagrams ❙ Example: security ❙ vague interfaces (“responsibilities”) ❙ Example: global performance ❙ vague associations (ignore navigability) ❚ Requirements document describes all ❙ stereotype classes: other requirements -

Modelling Interactions

University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Lecture 15: Modelling System Interactions Interactions with the new system How will people interact with the system? When/Why will they interact with the system? Use Cases introduction to use cases identifying actors identifying cases Advanced features Sequence Diagrams Temporal ordering of events involved in a use case © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. This presentation is available free for non-commercial use with attribution under a creative commons license. 1 University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Moving towards specification What functions will the new system provide? How will people interact with it? Describe functions from a user’s perspective UML Use Cases Used to show: the functions to be provided by the system which actors will use which functions Each Use Case is: a pattern of behavior that the new system is required to exhibit a sequence of related actions performed by an actor and the system via a dialogue. An actor is: anything that needs to interact with the system: a person a role that different people may play another (external) system. © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. This presentation is available free for non-commercial use with attribution under a creative commons license. 2 University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Use Case Diagrams Capture the relationships between actors and Use Cases Change a client contact Campaign Staff contact Manager Add a new client Record client payment Accountant © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. This presentation is available free for non-commercial use with attribution under a creative commons license. 3 University of Toronto Department of Computer Science Notation for Use Case Diagrams Use case Change client contact Staff contact Actor Communication association System boundary © 2004-5 Steve Easterbrook. -

Plantuml Language Reference Guide (Version 1.2021.2)

Drawing UML with PlantUML PlantUML Language Reference Guide (Version 1.2021.2) PlantUML is a component that allows to quickly write : • Sequence diagram • Usecase diagram • Class diagram • Object diagram • Activity diagram • Component diagram • Deployment diagram • State diagram • Timing diagram The following non-UML diagrams are also supported: • JSON Data • YAML Data • Network diagram (nwdiag) • Wireframe graphical interface • Archimate diagram • Specification and Description Language (SDL) • Ditaa diagram • Gantt diagram • MindMap diagram • Work Breakdown Structure diagram • Mathematic with AsciiMath or JLaTeXMath notation • Entity Relationship diagram Diagrams are defined using a simple and intuitive language. 1 SEQUENCE DIAGRAM 1 Sequence Diagram 1.1 Basic examples The sequence -> is used to draw a message between two participants. Participants do not have to be explicitly declared. To have a dotted arrow, you use --> It is also possible to use <- and <--. That does not change the drawing, but may improve readability. Note that this is only true for sequence diagrams, rules are different for the other diagrams. @startuml Alice -> Bob: Authentication Request Bob --> Alice: Authentication Response Alice -> Bob: Another authentication Request Alice <-- Bob: Another authentication Response @enduml 1.2 Declaring participant If the keyword participant is used to declare a participant, more control on that participant is possible. The order of declaration will be the (default) order of display. Using these other keywords to declare participants -

Methodological and Analytical Expertise in Socio-Technological

Paper prepared for the Conference Proceedings of the International System Dynamics Conference in Washington DC USA, July, 2011 How does the Multi-Level Perspective help to enhance a System Dynamics analysis of a specific transition challenge? Silvia Ulli-Beer 1, Stefan Grösser 2 and Alexander Wokaun 1 [email protected] ; [email protected] ; [email protected] 1Paul Scherrer Institut, Dynamics of Innovative Systems, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland 2University of St. Gallen, Institute of Management (IfB), Dufourstrasse 40a, 9000 St. Gallen, Switzerland 2University of Bern, Interdisciplinary Center for General Ecology (IKAÖ), Schanzeneckstr. 1, 3001 Bern, Switzerland Abstract This paper addresses the challenge of identifying adequate theoretical starting points for problem oriented simulation studies of socio-technical transitions towards near fossil free energy services e.g. for housing and transportation. The identification of adequate starting points for simulation studies is becoming increasingly important for the generalization of simulation results as well as for theory refinement. We found that the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) offers a helpful language for a modelling experiment based in a feedback perspective. This allows the conceptualization of a socio-technical transition challenge departing from an inter-subjective and hence scientific starting point. In addition feedback modelling appears to be a promising mathematical analysis approach that helps to substantiate the MLP. We have seen that the insights of the simulation experiment corroborate basic assumptions of the MLP concerning multi-level alignment processes but also discriminate the decisive determinants and governance mechanisms that explain radical innovation and subsequently the creation of path dependency. 1. Introduction This paper addresses the challenge of identifying adequate theoretical starting points for problem oriented simulation studies of socio-technical transitions towards near fossil free energy services e.g.