Seoul Environmnent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Distributions of Carbon Storage and Uptake of Urban Forests in Seoul, South Korea

Sensors and Materials, Vol. 31, No. 11 (2019) 3811–3826 3811 MYU Tokyo S & M 2051 Spatial Distributions of Carbon Storage and Uptake of Urban Forests in Seoul, South Korea Do-Hyung Lee,1 Sung-Ho Kil,2* Hyun-Kil Jo,2 and Byoungkoo Choi3 1Green Business Division, Korea Research Institute on Climate Change, Chuncheon 24239, South Korea 2Department of Ecological Landscape Architecture Design, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, South Korea 3Department of Forest Environment Protection, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, South Korea (Received August 17, 2019; accepted October 23, 2019) Keywords: climate change, ecosystem service, tree cover, vegetation index, forest management Urban forests are crucial to alleviate climate change by reducing the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. Although recent research has mapped the ecosystem service worldwide, most studies have not obtained accurate results owing to the usage of high-cost and low-resolution data. Hence, herein, carbon storage and carbon uptake per capita are quantified and mapped for all administrative districts of the Seoul Metropolitan City through (1) the analysis of tree cover via on-site tree investigation and aerial imagery and (2) geographic information system (GIS) analysis, targeting the Seoul Metropolitan City of South Korea, which has achieved the highest level of development. Results indicate that the total carbon storage and carbon uptake of Seoul are approximately 1459024 t and 147388 t/yr, respectively; the corresponding per unit area values are approximately 24.03 t/ha and 2.43 t/ha/yr, which are lower than those of other cities. In particular, carbon storage and uptake per capita benefits of the urban areas, except for the urban forest areas, are confirmed to show a maximum difference (~20 times) between the regions. -

The Gangnam-Ization of Korean Urban Ideology

Chapter 7 The Gangnam-ization of Korean Urban Ideology Bae-Gyoon Park and Jin-bum Jang 1 Introduction If there is one key word that could characterize contemporary Korean cities, it would be ‘apartments’.1 Single-unit housing was a dominant mode of residence in Korea before the 1980s, but the construction of apartments and multi-unit homes has rapidly increased since then. In particular, the development of mas- sive new towns in the Seoul Metropolitan Area from 1989 onward has triggered a flood in the supply of apartments, ushering in a transition to apartment life for most Koreans. Reflecting on this transformation, Gelézeau (2007) dubs Ko- rea the “apartment republic.” Other scholars have also noted how the sudden apartmentization of the country has shaped middle class cultural life (Park H., 2013) and has led to the virtual destruction of previously existing urban com- munities (Park C., 2013). A second key word that characterizes Korea’s urban transformations is ‘new town’. Through the 1980 Housing Site Development Promotion Act, the Korean state supported the construction of several new towns around the country, including Bundang and Ilsan in the Seoul Metro- politan Area. Facing rapid urbanization and a sharp increase in housing de- mand in some cities, the central government sought to quickly develop a large supply of affordable housing. In 1981, it designated and developed eleven new town sites through the Housing Site Development Promotion Act. By Decem- ber 2016, a total of 617 new towns had been developed through the act, ac- counting for a total of 2.5% of the country’s total land area and 24.4% of its urban housing. -

The Social Construction of Inequality in Gangnam District, Seoul1

Jung In KIM, Matjaž URŠIČ* BESIEGED CITIZENSHIP – THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF INEQUALITY IN GANGNAM DISTRICT, SEOUL1 Abstract. Through an illustrative comparison of squat- ter settlements and gentrified spaces, this study traces the genealogy and formation of extreme poverty at the heart of the most affluent district in Seoul. A site of urban struggle, the villages of Poi and Guryong did not start as spontaneous informal settlements, but as relocated camps of deprivileged social groups whose dislocation was forced by state authorities. After three decades, the Poi and Guryong villages have grown to become contested sites and polar opposites of the hous- ing complex of Tower Place that has is today one of the trendiest neighbourhoods in Seoul. On one hand, the Poi and Guryong villages provide a solid commu- 74 nity space for those displaced, yet one which has now become exceptionally valuable real estate that officials wish to reclaim for new development. The article analy- ses the conflict between residents and entails more than any simple narration of the poor’s disenfranchisement and raises the question of the social construction of ine- qualities and poverty in Seoul. Keywords: squatter settlement, urban development, state planning, Gangnam, citizenship Introduction Modern-day Seoul contains rare and sparsely dispersed enclaves of urban squatters, a few of the last relics of past urbanisation (Cho, 1997; Chung and Lee, 2015; Yonhap, 2017). Paralleling contemporary scenes of urban poverty in East Asia, those urban enclaves of poor people and their everyday life juxtapose manifestations of inequality and injustice against * Jung In Kim, PhD, Professor, Soongsil University, Seoul, South Korea; Matjaž Uršič, PhD, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. -

8. Integrated Energy Supply Program

8. Integrated Energy Supply Program Writer : Korea District Heating & Cooling Association Vice President Tae-Il Han Policy Area: Environment Integrated Energy Supply Program 227 1. General Background & Overview: Integrated Energy Supply in Seoul The supply of integrated energy to apartment complexes in Korea began in Seoul. South Korea is highly dependent on other countries for its energy, and the supply of integrated energy is essential as it promotes energy conservation on a large scale to preserve the environment and reduce the burden on citizens. When the Energy Use Rationalization Act was enacted in 1980, it included stipulations on the supply of inte- grated energy, but the method was very unfamiliar and required prohibitive investment in the early stages, making it impossible for ordinary entities to participate. Being an extremely overpopulated city, Seoul was in dire need of residential apartments and needed to disperse its concentrated population. With the development of new residential land, Seoul became the first city in South Korea to adopt an integrated energy supply. Toward the end of 1982, plans were devised to create a new built-up area in Mok-dong, something which was kept under wraps to prevent real estate speculation, under leadership of the late Kim Jae-ik (killed in the Aung San terror bombing incident), the former Senior Secretary to the President for Economic Affairs. Provision of energy to La Défense (on the outskirts of Paris, France) was used as the benchmark for an inte- grated energy supply model. As Seoul was the first South Korean city to adopt this model, the Ordinance on the Construction & Operation of the Integrated Energy Supply System was passed in 1983, and the Korea Energy Management Corporation (KEMCO), an institution designed to save energy, was commissioned with the task. -

교통 4 P49 Three Innovations of Subway Line 9.Pdf

Seoul Policies That Work: Transportation Three Innovations of Subway Line 9: Financing, Speed Competitiveness and Social Equity Shin Lee / Yoo Gyeong Hur, University of Seoul1 1. Policy Implementation Period 1994: Established route network 2009: Opened the 1st (Phase 1) section from Gaewha to Shin Nonhyeon stations 2015: Additionally opened the 2nd (Phase 2) section of Eonju, Seonjeongneung, Samsung Jungang, Bongeunsa and Sports Complex stations 2017: Expected to open the 3rd (Phase 3) section from Samjeon Jct. to Seoul Veterans Hospital stations Source: JoongAng Ilbo [Cover Story] Daily lives changed by Subway Line 9, in 9 months after the opening of Seoul’s Subway Line 9 extension Seoul Subway Line 9 is a route that connects the southern part of the Han River from the east to west. The first (Phase 1) section, completed in 2009, stretches 25.5kmand connects Gangnam and Gangseo, Seoul by being operated from Gimpo Airport to Banpo through Yeoui-do. The second (Phase 2) section of Eeonju, Seonjeongneung, Samsung Jungang, Bongeunsa and Sports Complex stations were additionally opened in March 2015. Subway Line 9 is connected to most of the lines in the city (except for Subway Lines 6 and 8), and it is the only line in Seoul that operates an express line in the entire system. It was constructed through private investment for the first time in Korea as an urban rail transit and promoted by a public-private partnership (PPP) project in the Build-Transfer-Operate (BTO) that transfers the ownership of the facilities to the Seoul metropolitan government after the completion and allows private investors to gain benefits from investment for 30 years of operation in accordance with the agreement with the Seoul Metropolitan Government. -

Great Attractions of the Hangang the Hangang with 5 Different Colors

Great Attractions of the Hangang The HANGANG WIth 5 DIFFERENT COLORS Publisher_ Mayor Oh Se-Hoon of Seoul Editor_ Chief Director Chang Jung Woo of Hangang Project Headquarters Editorial board member_ Director of General Affairs Bureau Sang Kook Lee, Director of General Affairs Division So Young Kim, Director of Public Relations Division Deok Je Kim, Cheif Manager of Public Relations Division Ho Ik Hwang Publishing Division_ Public Relations Division of Hangang Project Headquarters (02-3780-0773) * Seoul Metropolitan Goverment, All rights reserved Best Attractions with 5 different colors Here, there are colors representing Korea, yellow, blue, white and black. These are the 5 directional colors called ‘o-bang-saek’ in Korean. Based on Yín-Yáng Schòol, our ancestors prayed for good luck and thought those colors even drove bad forces out. To Koreans, o-bang-saek is more than just a combination of colors. It is meaningful in various areas such as space, philosophy, wisdom, etc. While o-bang-saek is representative color of Korea, the space representing Korea is the Hangang (river). Having been the basis of people’s livelihood, the Hangang flows through the heart of Seoul and serves as the space linking nature, the city and human beings. So let’s take a look at the river through the prism of o-bang-saek, the traditional color of Korea. Tourist attractions of the river that used to move in a silver wave are stretched out in 5 different colors. CONTENTS WHITE. Rest·CULTURE coMPLEX BLACK. HANGANGLANDscAPes Free yourself from the routine Discover the beauty BEST AttractIONS WIth 5 DIFFereNT coLors and have an enjoyable time hidden along the water river BLUE. -

Discovering a Biophilic Seoul a Thesis Submitted to The

DISCOVERING A BIOPHILIC SEOUL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREES MASTER OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING MASTER OF SCIENCE DISCOVERING A BIOPHILIC SEOUL BY UNAI MIGUEL ANDRES DR. SANGLIM YOO – ADVISOR DR. JOSHUA GRUVER – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 DISCOVERING A BIOPHILIC SEOUL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREES MASTER OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING MASTER OF SCIENCE BY UNAI MIGUEL ANDRES Committee Approval: ___________________________________ ___________________________ Committee Chairperson Date ___________________________________ ___________________________ Committee Co-chairperson Date ___________________________________ ___________________________ Committee Member Date Departmental Approval: ___________________________________ ___________________________ Departmental Chairperson Date ___________________________________ ___________________________ Departmental Chairperson Date ___________________________________ ___________________________ Dean of Graduate School Date BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 i ABSTRACT THESIS: Discovering a Biophilic Seoul STUDENT: Unai Miguel Andres DEGREES: Master of Science; Master of Urban and Regional Planning COLLEGE: Sciences and Humanities; Architecture and Planning DATE: May 2017 PAGES: Despite being inhabited for more than 2000 years; the city of Seoul grew in isolation from Western cultures until the 19th century. However, because of being almost destroyed during the Korean War, the city spent most of the second half of the 20th century trying to rebuild itself. After recovering, Seoul shifted its policies to become a sustainable development-oriented city. Thus, the city engaged in its first major nature recovery project, the Mt. Namsan Restoration project, in 1991 and it enacted the first 5-year Plan for Park & Green Spaces in 1996, which pinpointed the start of the Green Seoul era. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Standard Disclaimer: This report is a joint product between the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and Seoul Metropolitan Government. It is written by a team from University of Seoul with technical advice from the World Bank team. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permis- sion may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978- 750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Changes in Park & Green Space Policies in Seoul

Changes in Park & Green Space Policies in Seoul Date 2015-06-25 Category Environment Updater ssunha This report explores the park and green space policies of the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) by period, from the time Korea opened its ports to the outside world until today. The periods are: modernization and Japanese colonial rule; the first and second republics; the third and fourth republics; the fifth and sixth republics; and local autonomous government administrations elected by popular vote. For each period, this report examines the institutional and spatial changes in urban parks. Modernization & Japanese Colonial Rule: The Dawn of Urban Parks Defining Characteristics: Mountains and valleys serving as parks (Joseon Dynasty); Independence Park (Open-door Period); destruction of cultural heritage (Japanese colonial government) The concept of parks and green spaces as planned facilities was introduced as a byproduct of modernization in the late 19th and early 20th century. Of course there had been places that served as parks and green spaces ever since the Kingdom of Joseon moved its capital to today’s Seoul in 1394. The city is surrounded by an inner ring of 4 mountains and an outer ring of another 4 mountains, with the Han River flowing east to west. During the Joseon Dynasty, the walled city was located to the north of the Han, and the significance of the inner ring of Bugak Mountain, Inwang Mountain, Nak Mountain, and Nam Mountain was profound as the city walls were built on their ridges. Scholars of old would visit nearby mountain valleys where they wrote and recited poems for leisure. -

Truth and Reconciliation� � Activities of the Past Three Years�� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

Truth and Reconciliation Activities of the Past Three Years CONTENTS President's Greeting I. Historical Background of Korea's Past Settlement II. Introduction to the Commission 1. Outline: Objective of the Commission 2. Organization and Budget 3. Introduction to Commissioners and Staff 4. Composition and Operation III. Procedure for Investigation 1. Procedure of Petition and Method of Application 2. Investigation and Determination of Truth-Finding 3. Present Status of Investigation 4. Measures for Recommendation and Reconciliation IV. Extra-Investigation Activities 1. Exhumation Work 2. Complementary Activities of Investigation V. Analysis of Verified Cases 1. National Independence and the History of Overseas Koreans 2. Massacres by Groups which Opposed the Legitimacy of the Republic of Korea 3. Massacres 4. Human Rights Abuses VI. MaJor Achievements and Further Agendas 1. Major Achievements 2. Further Agendas Appendices 1. Outline and Full Text of the Framework Act Clearing up Past Incidents 2. Frequently Asked Questions about the Commission 3. Primary Media Coverage on the Commission's Activities 4. Web Sites of Other Truth Commissions: Home and Abroad President's Greeting In entering the third year of operation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea (the Commission) is proud to present the "Activities of the Past Three Years" and is thankful for all of the continued support. The Commission, launched in December 2005, has strived to reveal the truth behind massacres during the Korean War, human rights abuses during the authoritarian rule, the anti-Japanese independence movement, and the history of overseas Koreans. It is not an easy task to seek the truth in past cases where the facts have been hidden and distorted for decades. -

Brian Allgood Army Community Hospital Command Suite

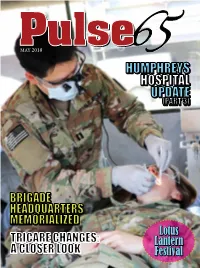

MAY 2018 HUMPHREYSHUMPHREYS HOSPITALHOSPITAL UPDATEUPDATE (PART(PART 3)3) BRIGADEBRIGADE HEADQUARTERSHEADQUARTERS MEMORIALIZEDMEMORIALIZED Lotus TRICARE CHANGES: Lantern A CLOSER LOOK FestivalFestival Dental Program We Put You First Navy Federal Credit Union serves the military, Coast Guard, veterans and their families. When you’re a member, you benefit from a lifelong relationship with a financial institution that makes your financial goals a priority. • More than 300 branches worldwide, many located on or near bases • 24/7 access to stateside member reps • Thousands of free ATMs1 nationwide and fee rebates2 • Digital banking3 anytime, anywhere • Early access to military pay with Direct Deposit VISIT US TODAY. Camp Carroll, Osan AB, Yongsan, Camp Henry and Camp Humphreys (2 locations to serve you) navyfederal.org Federally insured by NCUA. 1There are no fees for members who use their Navy Federal Debit Card at CO-OP Network® ATMs, in addition to participating California Walgreens. 2Up to $10 per statement period with e-Checking, Flagship, and Campus Checking accounts; up to $20 per statement period with Active Duty Checking®. Direct deposit required in order to receive fee rebates for Flagship Checking. 3Message and data rates may apply. Visit navyfederal.org for more information. Image used for representational purposes only; does not imply government endorsement. © 2018 Navy Federal NFCU 11445 (4-18) 11445_CE_Seoul Survival_Ad_April18_BGA.indd 1 4/13/18 9:29 AM EDITOR’S LETTER B 14IA0802 Artwork# ear readership of the PULSE 65, WELCOME to the eleventh edition of a new publication highlighting all things medi- Dcal, dental, veterinary and public health throughout the peninsula. Throughout this issue you will find a wealth of information to include the clinical phone directory, the continuing series on how to navigate a Korean hospital and a variety of photos and stories covering the units within the 65th Medical Brigade. -

Seoulbuing Buing!

SEOUL Buing Buing! Seoul (pronounced soul) is the capital and largest the Three Kingdoms of Korea. It continued Dongdaemun Design Plaza, Lotte World, metropolis of South Korea. The Seoul as the capital of Korea under the Joseon the world's second largest indoor theme park, Capital Area, which includes the surrounding Dynasty and the Korean Empire. The Seoul and Moonlight Rainbow Fountain, the world's Incheon metropolis and Gyeonggi province metropolitan area contains four UNESCO longest bridge fountain. The birthplace of is the world’s second largest metropolitan World Heritage Sites: Changdeok Palace, K-pop and the Korean Wave, Seoul was voted area with over 25.6 million people, home Hwaseong Fortress, Jongmyo Shrine and the world's most wanted travel destination by to over half of South Koreans along with the Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty. Chinese, Japanese and Thai tourists for three 632,000 international residents. consecutive years in 2009–2011 with over 12 Seoul is surrounded by mountains, the million international visitors in 2013, making it Situated on the Han River, Seoul's history tallest being Mt. Bukhan, the world's most East Asia's most visited city and the world's 7th stretches back more than 2,000 years when visited national park per square foot. biggest earner in tourism. it was founded in 18 BCE by Baekje, one of Modern landmarks include the iconic Gyeongbokgung Palace Was the first royal palace built by the Joseon palaces during their occupation of Dynasty, three years after the Joseon Korea (1910 – 1945). Most of the Dynasty was founded.