Transitional Justice and Its Role in Development in Post-Conflict Northern Uganda Jessica Chirichetti SIT Study Abroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda-A-Digital-Rights-View-Of-The

echnology and in Uganda A Digital Rights View of the January 2021 General Elections Policy Brief December 2020 VOTE Technology and Elections in Uganda Introduction As Uganda heads to presidential and parliamentary elections in January 2021, digital communications have taken centre-stage and are playing a crucial role in how candidates and parties engage with citizens. The country's electoral body decreed in June 2020 that, due to social distancing required by COVID-19 standard operating procedures, no physical campaigns would take place so as to ensure a healthy and safe environment for all stakeholders.1 Further, Parliament passed the Political Parties and Organisations (Conduct of Meetings and Elections) Regulations 2020,2 which aim to safeguard public health and safety of political party activities in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and, under regulation 5, provide for holding of political meetings through virtual means. The maximum number of persons allowed to attend campaign meetings was later set at 70 and then raised to 200.3 The use of the internet and related technologies is growing steadily in Uganda with 18.9 million subscribers, or 46 internet connections for every 100 Ugandans.4 However, radio remains the most widely accessible and usable technology with a penetration of 45%, compared to television at 17%, and computers at 4%.5 For the majority of Ugandans, the internet remains out of reach, particularly in rural areas where 75.5% of Ugandans live. The current election guidelines mean that any election process that runs predominantly on the back of technology and minimal physical organising and interaction is wont to come upon considerable challenges. -

A Diplomatic Surge for Northern Uganda

www.enoughproject.org A DIPLOMATIC SURGE FOR NORTHERN UGANDA By John Prendergast and Adam O’Brien Strategy Briefing #9 December 2007 I. INTRODUCTION U.S. engagement, a necessary but largely neglected Dissension, disarray, deaths, and defections within key to success, has become more visible and the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army leadership provide concerted in recent months. The United States is a major opportunity for negotiators to pursue—par- providing financial support for the consultation allel to an expeditious conclusion of the formal process and a special advisor for conflict resolution negotiations process in Juba—the conclusion of has been named to support peace efforts over the a swift deal with LRA leader Joseph Kony himself. objections of key State Department officials.2 These Such a deal would seek to find an acceptable set are overdue steps in the right direction, but much of security and livelihood arrangements for the LRA more can be done. leadership—particularly those indicted by the Inter- national Criminal Court—and its rank and file. This To keep the peace process focused and moving moment of weakness at the top of the LRA must forward, several steps are necessary from the be seized upon immediately. If diplomats don’t, the Juba negotiators, the U.N. Special Envoy, and the LRA’s long-time patron, the government of Sudan, United States: will eventually come to Kony’s rescue as it has in the past, and new life will be breathed into the • Deal directly with Kony on the core issues: Ad- organization in the form of weapons and supplies. -

Country Advice Uganda – UGA36312 – Central Civic Education Committee

Country Advice Uganda Uganda – UGA36312 – Central Civic Education Committee – Democratic Party – Uganda Young Democrats – Popular Resistance Against Life Presidency – Buganda Youth Movement 9 March 2010 Please provide information on the following: 1. Leadership, office bearers of the Central Civic Education Committee (CVEC or CCEC) since 1996. The acronym used in sources for the Central Civic Education Committee‟s is CCEC. As of 10 January 2008, the CCEC was initially headed by Daudi Mpanga who was the Minister for Research for the south central region of Buganda according to Uganda Link.1 On 1 September 2009 the Buganda Post reported that the committee was headed by Betty Nambooze Bakireke.2 She is commonly referred to as Betty Nambooze. Nambooze was Democratic Party spokeswoman.3 The aforementioned September 2009 Buganda Post article alleged that Nambooze had been kidnapped and tortured by the Central Government for three days. She had apparently been released due to international pressure and, according to the Buganda Kingdom‟s website, the CCEC had resumed its duties.4 In a November 2009 report, the Uganda Record states that Nambooze had subsequently been arrested, this time in connection with the September 2009 riots in Kampala.3 The CCEC was created by the Kabaka (King) of Buganda in late 2007 or early 2008 according to a 9 January 2008 article from The Monitor. The CCEC was set up with the aim to “sensitise” the people of Buganda region to proposed land reforms.5 The previously mentioned Buganda Post article provides some background on the CCEC: The committee, which was personally appointed by Ssabasajja Kabaka Muwenda Mutebi, is credited for awakening Baganda to the reality that Mr. -

The Uganda Law Society 2Nd Annual Rule of Law

THE UGANDA LAW SOCIETY 2ND ANNUAL RULE OF LAW DAY ‘The Rule of Law as a Vehicle for Economic, Social and Political Transformation’ Implemented by Uganda Law Society With Support from Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and DANIDA WORKSHOP REPORT Kampala Serena Hotel 8th October 2009 Kampala – UGANDA 1 Table of Contents T1.T Welcome Remarks – President Uganda Law Society ....................................3 2. Remarks from a Representative of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung...................3 3. Presentation of Main Discussion Paper – Hon. Justice Prof. G. Kanyeihamba............................................................................................................4 4. Discussion of the Paper by Hon. Norbert Mao ...............................................5 5. Discussion of the Paper by Hon. Miria Matembe...........................................6 6. Keynote Address by Hon. Attorney General & Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs Representing H.E the President of Uganda. ...................7 7. Plenary Debates .................................................................................................7 8. Closing...............................................................................................................10 9. Annex: Programme 2 1. Welcome Remarks – President Uganda Law Society The Workshop was officially opened by the President of the Uganda Law Society, Mr. Bruce Kyerere. Mr. Kyerere welcomed the participants and gave a brief origin of the celebration of the Rule of Law Day in Uganda. The idea was conceived -

UGANDA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

UGANDA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 20 April 2011 UGANDA DATE Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN UGANDA FROM 3 FEBRUARY TO 20 APRIL 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON UGANDA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 3 FEBRUARY AND 20 APRIL 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Political developments: 1962 – early 2011 ......................................................... 3.01 Conflict with Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): 1986 to 2010.............................. 3.07 Amnesty for rebels (Including LRA combatants) .............................................. 3.09 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Kampala bombings July 2010 ............................................................................. 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION.......................................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .................................................................................................. -

Exclusionary Elite Bargains and Civil War Onset: the Case of Uganda

Working Paper no. 76 - Development as State-making - EXCLUSIONARY ELITE BARGAINS AND CIVIL WAR ONSET: THE CASE OF UGANDA Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre August 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © S. Lindemann, 2010 This document is an output from a research programme funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development. However, the views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Crisis States Research Centre Exclusionary elite bargains and civil war onset: The case of Uganda Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre Uganda offers almost unequalled opportunities for the study of civil war1 with no less than fifteen cases since independence in 1962 (see Figure 1) – a number that makes it one of the most conflict-intensive countries on the African continent. The current government of Yoweri Museveni has faced the highest number of armed insurgencies (seven), followed by the Obote II regime (five), the Amin military dictatorship (two) and the Obote I administration (one).2 Strikingly, only 17 out of the 47 post-colonial years have been entirely civil war free. 7 NRA 6 UFM FEDEMO UNFR I FUNA 5 NRA UFM UNRF I FUNA wars 4 UPDA LRA LRA civil HSM ADF ADF of UPA WNBF UNRF II 3 Number FUNA LRA LRA UNRF I UPA WNBF 2 UPDA HSM Battle Kikoosi Maluum/ UNLA LRA LRA 1 of Mengo FRONASA 0 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Figure 1: Civil war in Uganda, 1962-2008 Source: Own compilation. -

Brochure 2.Indd

NNORBERTORBERT 10 REASONS WHY I DESERVE YOUR VOTE - MY RECORD AND POTENTIAL - 1. I am a tireless peace crusader who initiated groundbreaking debates in Parliament, among the civil society and the international commu- MMAOAO nity. As a Local Government leader I have trans- formed Gulu to a booming and business friendly FFOROR PPRESIDENTRESIDENT destination. 2. Due to my leadership, Northern Uganda now has a strong issue-based identity backed by vibrant grassroot organisations empowered to speak out for their interests. 3. Due to my consistent, insistent and persuasive advocacy, funds have been committed by inter- national donors towards humanitarian assist- ance, reconstruction, peace building initiatives, and support to NGOs, health, education and lo- cal government programs thus promoting the Charismatic wellbeing and welfare of the people. 4. In Northern Uganda, due to my example, crook and crony political leadership has largely been replaced by the entrenchment of upright, truthful and honest leadership, which has restored sanity, visibility and dignity to our national profile as a community. 5. The trend towards self-destruction in Northern Uganda has been stopped by turning to the initiative and ability of our people to take responsibility for their future rather than rely solely on government initia- tives. 6. I have spearheaded the most vibrant nationwide and international debate on the conflict in Northern Uganda and has ensured that the issues of peace and reconstruction are firmly on the national and global agenda. 7. I am business friendly. I have encouraged private investors in sectors like agriculture, banking, education and health. 8. I am a leader who is guided by long-range principles, not short-term expediency. -

AKBAR HUSSEIN GODI's CORRECTIONAL STORY NEXT of KIN: MR. AIMARR FIDEL KAMPALA PRISON NO. KGC447/15 ANECDOTE My Further and B

AKBAR HUSSEIN GODI’S CORRECTIONAL STORY NEXT OF KIN: MR. AIMARR FIDEL KAMPALA PRISON NO. KGC447/15 ANECDOTE My further and better particulars are thus, I’m resident of Entebbe road, Najjanankumbi, Kampala, aged 35, Lawyer by profession, a prisoner serving prison term in the Kigo prison Facility. I’m also father of two boys aged seven and eight respectively, orphaned at six years. I dropped out of school after senior one and started to take a living on my own at the teenage age of 15, this led me to a good Samaritan a one Dr. Bua who I think was God sent who offered to pay for me school fees. As I itched to commence studies after a year, Dr. Bua who was working with the Save the Children Fund (UK), Arua sub office soon got a better job with the United Nations in Serbia at a time when Mobile phones were just making entry, thus I lost his contact and once again dropped out of school. I always convinced myself never to give up easily, especially, when faced with challenges. I quickly picked up the pieces with some savings. I commenced a petty business which within a year enabled me raise school fees for a day school, the result was a first grade aggregate 20 in UCE in 1999. Energized, I diversified to photography, after selling off the petty kiosk business, I relocated to Kampala and quickly enrolled for private study at St. Matia Mulumba Church opposite old Kampala police where I sat privately and obtained 13 points in my UACE. -

Clarification on Hon. Norbert Mao's

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION Plot 55 Jinja Road Telephone: +256-41-337500/337508-11 P. O. Box 22678 Kampala,Uganda Fax: +256-31-262207/41-337595/6 Website: www.ec.or.ug E-mail: [email protected] rd Adm72/01 Date: 3............................................. December 2015 Ref: ………………………………………… Press Release Clarification on Hon. Norbert Mao’s failed bid for Nomination as a Parliamentary Candidate On 2nd December 2015, Hon. Norbert Mao presented himself for nomination for Member of Parliament, Gulu Municipality, Gulu District. However, the Returning Officer could not nominate him because his name was not found on the National Voters Register, which is a requirement for nomination under Section 4 (1) (b) of the Parliamentary Elections Act of 2005 (as amended). The Electoral Commission has noted the false commentaries that have arisen out of this failed bid for nomination of Hon. Norbert Mao, and would like to clarify on the matter as follows: 1. The Electoral Commission compiled a National Voters’ Register for purposes of the 2015-2016 General Elections, and for this purpose, extracted the data containing the particulars of registered and verified Ugandan citizens from the National Identification Register; 2. The extracted data of the successfully verified Ugandan citizens was displayed for public scrutiny at the respective update centers in each Parish/Ward during the update period from 7th April to 11th May 2015. The exercise had been scheduled to end on 30th April 2015 but was extended twice, from 30th April to 4th May, and again, to 11th May 2015; 3. During the above period, the Commission conducted an update of the National Voters’ Register, which involved fresh registration of Ugandan citizens of 18 years and above, who had missed out on the registration conducted for purpose of issuance of a National Identity Card. -

HOSTILE to DEMOCRACY the Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda

HOSTILE TO DEMOCRACY The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ London $$$ Brussels Copyright 8 August 1999 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-239-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-65985 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. -

A Disjointed Effort: an Analysis of Government and Non-Governmental Actors’ Coordination of Reintegration Programs in Northern Uganda Nicole Compton SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2014 A Disjointed Effort: An Analysis of Government and Non-Governmental Actors’ Coordination of Reintegration Programs in Northern Uganda Nicole Compton SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Compton, Nicole, "A Disjointed Effort: An Analysis of Government and Non-Governmental Actors’ Coordination of Reintegration Programs in Northern Uganda" (2014). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1920. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1920 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Disjointed Effort: An analysis of government and non-governmental actors’ coordination of reintegration programs in northern Uganda By: Nicole Compton Academic Advisor: Paul Omach Academic Director: Martha Wandera SIT Study Abroad, Uganda Post Conflict Transformation Fall 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to first thank my parents for providing me with the opportunity to study abroad in Uganda and supporting me throughout the semester. I would also like to thank the SIT staff for facilitating a remarkable semester and providing constant advice throughout the ISP period. In addition, I greatly appreciate the time and assistance provided to me by my respondents and my ISP advisor, Paul Omach. -

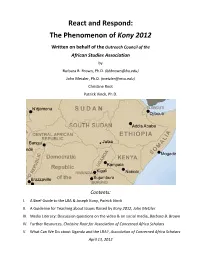

React and Respond: the Phenomenon of Kony 2012

React and Respond: The Phenomenon of Kony 2012 Written on behalf of the Outreach Council of the African Studies Association by Barbara B. Brown, Ph.D. ([email protected]) John Metzler, Ph.D. ([email protected]) Christine Root Patrick Vinck, Ph.D. Contents: I. A Brief Guide to the LRA & Joseph Kony, Patrick Vinck II. A Guideline for Teaching about Issues Raised by Kony 2012, John Metzler III. Media Literacy: Discussion questions on the video & on social media, Barbara B. Brown IV. Further Resources, Christine Root for Association of Concerned Africa Scholars V. What Can We Do about Uganda and the LRA?, Association of Concerned Africa Scholars April 13, 2012 A Brief Guide to the LRA & Joseph Kony From 1987 to 2006, the violent rebel Lord's the civilians, accusing them of aiding the Resistance Army (LRA) fought the Ugandan government in seeking his defeat. Kony’s government and terrorized the northern military campaigns became increasingly Ugandan population. The fighting was rooted focused on “cleansing” the Acholi population, in a longstanding divide between Uganda’s although he also preyed on civilians in north and south.1 Today, the LRA is reduced neighboring regions. to about 200 militia members, due to defections and to military attacks on them. In The conflict in northern Uganda escalated, 2006 they left Uganda but continue to resulting in large‐scale killings and plunder in neighboring countries mutilations. By the end of 2005, more than 1.8 million people were displaced and moved The Origins into camps. To fill its ranks, the LRA abducted as many as 60,000 civilians, often children, to Armed conflict erupted in its current form serve as porters, soldiers, or sexual and after president Museveni, from southern domestic servants.