The Reason I Jump ||Dramaturgy Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Footer Text Here

1 | [footer text here] 2 | [footer text here] • The reason I wanted to give this talk is because I have come to understand that a lot of what we know for sure about autism, just isn’t so. We have developed services for autistic people which are based on the belief that autism is primarily a psychological problem characterized by deficits in social understanding, restricted behaviors and interests, and cognition. But I have come to believe that autism is better accommodated and supported when it is understood as a neurological condition. [pause] Increasingly, people working in a neurological paradigm are achieving remarkably good outcomes, especially for those who don’t speak or whose speech is unreliable communication, and for those with prominent symptoms of dyspraxia. Dyspraxia is difficulty coordinating movement. 3 | [footer text here] • Ten years ago, we thought that autism was a thing. Find the gene! Maybe it’s vaccines? It’s an epidemic and a crisis! We’ve mostly moved through that, thankfully. But remnants of it sometimes rear its ugly head on occasion. • A diagnosis of autism doesn’t correlate with any specific trait or characteristic. People can be super smart or have significant cognitive challenges. They can be organized or have executive function problems. They can be a competitive surfer or use a wheelchair. They may or may not have seizures. They may have normal, very acute or scrambled senses. They may be blind or deaf. They may be polite and regulated to a fault, or have significant anxiety, behavioral, or mental health problems. • Historically, autism was defined by psychiatrists who were rooted in early 20th Century cultural ideas about intelligence, eugenics, and social hygiene. -

The Persistence of Fad Interventions in the Face of Negative Scientific Evidence: Facilitated Communication for Autism As a Case Example

Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention ISSN: 1748-9539 (Print) 1748-9547 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tebc20 The persistence of fad interventions in the face of negative scientific evidence: Facilitated communication for autism as a case example Scott O. Lilienfeld, Julia Marshall, James T. Todd & Howard C. Shane To cite this article: Scott O. Lilienfeld, Julia Marshall, James T. Todd & Howard C. Shane (2014) The persistence of fad interventions in the face of negative scientific evidence: Facilitated communication for autism as a case example, Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 8:2, 62-101, DOI: 10.1080/17489539.2014.976332 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17489539.2014.976332 Published online: 02 Feb 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 5252 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tebc20 Download by: [University of Lethbridge] Date: 05 October 2015, At: 05:52 Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 2014 Vol. 8, No. 2, 62–101, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17489539.2014.976332 EBP Advancement Corner The persistence of fad interventions in the face of negative scientific evidence: Facilitated communication for autism as a case example Scott O. Lilienfeld1, Julia Marshall1, James T. Todd2 & Howard C. Shane3 1Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2Department of Psychology, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI, USA, 3Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA ................................................................................................................................................. Abstract Communication disorder and mental health professionals may assume that once novel clinical techniques have been refuted by research, they will be promptly abandoned. -

Book Review: the Reason I Jump: One Boy's Voice from the Silence of Autism by Naoki Higashida

Book Review: The Reason I Jump: One Boy's Voice from the Silence of Autism by Naoki Higashida Constantinos Mantzikos Special education teacher [email protected] Table 1. The book Below is a review of the book “The Reason I Jump: One Boy's Voice from the Silence of Autism”, written by Naoki Higashida. The author writes about autism. First of all, the author is an autistic man. He was born 1992 in Kimitsu, Japan and he received his original autism diagnosis in 1998. He has classic autism (Leo Kanner’s autism) and can’t talk effectively with speech. He developed an alternative communication system with an alphabet with his teacher. He wrote this book, because he wanted to show how he functions as an autistic person. Autism is the most known human condition and many scholars have studied this condition. This remarkable book promotes the real image of autism and autistic individuals. He gives us an exceptional chance to enter the mind of another and see the world from a strange and fascinating perspective. In this book there are 58 questions and answers from the author. He answers the most common questions, such as: Why do autistic individuals demonstrate stereotypical behaviors? Why do these people delay giving an answer to a question? Why can’t these people have eye contact? He gives answers in various fields, such as sensory issues and behavioral conditions. Naoki Higashida gives a better understanding of autism and he wants to know if we want to understand autism from the part of autistics, we can teach effectively these students. -

The Politics of Autism

The Politics of Autism The Politics of Autism Bryna Siegel, PhD 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Siegel, Bryna, author. Title: The politics of autism / by Bryna Siegel. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017053462 | ISBN 9780199360994 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Autism—Epidemiology—Government policy—United States. | Autism—Diagnosis—United States. | Autistic people—Education—United States. Classification: LCC RC553.A88 S536 2018 | DDC 362.196/8588200973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017053462 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America For David CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction xi 1. -

Book Title Author Category for Kids, Teens, Or Parents the Family

For Kids, Teens, or Book Title Author Category Parents The Family ADHD Solution Dr. Mark Bertin ADHD PARENTS Organizing the Disorganized Child Martin Kutscher & Marcella Moran ADHD PARENTS From Emotions to Advocacy Peter Wright & Pam Wright advocacy PARENTS Scaredy Squirrel (series) Melanie Watt anxiety KIDS Ron Rapee, Sue Spence, Vanessa Helping Your Anxious Child Cobham, Ann Wignall anxiety PARENTS Brotherly Feelings: Me, My Emotions, and My Brother with Asperger's Syndrome Sam Frender and Robin Schiffmiller autism KIDS The Real Experts: Readings for Parents of Autistic Children Michelle Sutton autism PARENTS The ABCs of Autism Acceptance Sparrow Rose Jones autism PARENTS Ido in Autismland Ido Kedar autism PARENTS The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Naoki Higashida autism PARENTS What Every Autistic Girl Wishes Her Parents Knew Autism Women's Network autism PARENTS Neurotribes Steve Silberman autism PARENTS My Name is Ryan and I have Autism Rachel Leydon autism PARENTS Ten Things Every Child With Autism Wishes You Knew Ellen Notbohm autism PARENTS Aspergirls – Empowering Females with Asperger Syndrome Rudy Simone autism PARENTS Look Me In the Eye John Elder Robison autism PARENTS Thinking in Pictures Temple Grandin autism PARENTS Be Different John Elder Robison autism PARENTS Autism in Your Classroom Deborah Fein and Michelle Dunn autism PARENTS School Success for Kids with Aspergers Stephan Silverman & Rich Weinfeld autism PARENTS Raising Your Spirited Child Mary Sheedy Kurcinka behavior PARENTS Discover Your Child's Learning Styles Mariaemma Willis and Victoria Hodson behavior PARENTS Lost at School Ross W. Greene behavior PARENTS The Explosive Child Ross W. -

A Boy Called Bat Educator's Resource

A BOY CALLED BAT EDUCATOR’S RESOURCE About the Book About the Author For Bixby Alexander Tam (nicknamed Bat), life Elana K. Arnold grew up in California, tends to be full of surprises—some of them good, where she was lucky enough to some of them not so good. Today, though, is a good have her own perfect pet—a surprise day. Bat’s mom, a veterinarian, has brought gorgeous mare named Rainbow— The lie I most often tell myself home a stray baby skunk, which she needs to take and a family who let her read when I am working is that I a writing fiction. It’s all made upm care of until she can hand him over to a wild- as many books as she wanted. I whisper; it’s just pretend , animal shelter. She is the author of picture . books, middle grade novels, and But the truth is, it is all truth But the minute Bat meets the kit, he knows they books for teens. She lives in . belong together. And he’s got one month to show The truth is, I love an autistic kid. The truth is, I know the Huntington Beach, California, his mom that a baby skunk just might make a pain of sibling rivalry. The truth is, I understand how it feels with her husband, two pretty terrific pet. to want something so much, so fiercely, that I become children, and a menagerie consumed by it, the way this boy called Bat wants to keep an Written by acclaimed author Elana K. -

Presume Competence a Professional and Community Handbook Informed by the Reason I Jump

Presume Competence A Professional and Community Handbook Informed by The Reason I Jump The reason I jump Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY Letters 3 advocacy workbook advisors USING THIS HANDBOOK for Professionals and Communities 4 Making Connections and Building Empathy 6 Inclusion and Belonging Awareness of the Challenges Reflecting on Your Practice 12 Presume Competence Practice Multiple Forms of Communication Alternative and Augmentative Communication and Spelling Sensory Perception: Art, Nature, Color, Sense, and Sound Fight Stigma, Build Capacity Through Community FIND YOUR COMMUNITY 24 WATCHING THE REASON I JUMP 23 Reflecting: Questions for Before and After Screenings GLOSSARY 25 INTRODUCTORY LETTERS Advocacy WoOKBOOK Advisors The reason I jumP impact team have convened a wide-reaching community of autistic individuals from around the world to advise on the film and the educational materials. The guide opens with advice to professionals and community members in their own words. The team of advisors, all of whom are nonspeaking with the exception of Leo Capella, have also contributed words of experience and advice to a Self-Advocacy Workbook available at TheReasonIJumpFilm.comLetters #. Dear Professional, Everyone thinks you are stupid if you cannot talk. You cannot access the curriculum and it was not possible for me to get a regular diploma. People see my body stims and either stare at me or laugh. Because the classrooms were not integrated, it was not possible to make friends with nondisabled peers. It is difficult to keep up with so many obstacles.Try to see my potential. —Emma Budway,Letters 23 years old, USA,# Advisor Dear Professional, To fully support us in the way that we need it’s extremely important to remember that we understand. -

The Reason I Jump

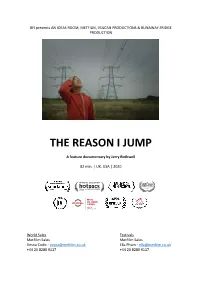

BFI presents AN IDEAS ROOM, METFILM, VULCAN PRODUCTIONS & RUNAWAY FRIDGE PRODUCTION THE REASON I JUMP A feature documentary by Jerry Rothwell 82 min. | UK, USA | 2020 World Sales Festivals MetFilm Sales MetFilm Sales Vesna Cudic - [email protected] Ella Pham - [email protected] +44 20 8280 9117 +44 20 8280 9117 LOGLINE Based on the best-selling book bY Naoki Higashida, THE REASON I JUMP is an immersive film exploring the experiences of nonspeaking autistic people from around the world. SYNOPSIS Based on the best-selling book bY Naoki Higashida, THE REASON I JUMP is an immersive cinematic exploration of neurodiversity through the experiences of nonspeaking autistic people from around the world. The film blends Higashida's revelatorY insights into autism, written when he was just 13, with intimate portraits of five remarkable Young people. It opens a window for audiences into an intense and overwhelming, but often joYful, sensorY universe. Moments in the lives of each of the characters are linked bY the journeY of a Young Japanese boY through an epic landscape; narrated passages from Naoki’s writing reflect on what his autism means to him and others, how his perception of the world differs, and whY he acts in the way he does: the reason he jumps. The film distils these elements into a sensuallY rich tapestrY that leads us to Naoki’s core message: not being able to speak does not mean there is nothing to say. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Naoki Higashida’s descriptions of a world without speech provoke us to think differentlY about autism. -

The Strange Case of Anna Stubblefield She Told the Family of a Severely Disabled Man That She Could Help Him to Communicate with the Outside World

https://nyti.ms/1MReJHh The Strange Case of Anna Stubblefield She told the family of a severely disabled man that she could help him to communicate with the outside world. The relationship that followed would lead to a criminal trial. By DANIEL ENGBER OCT. 20, 2015 Anna didn’t want to keep her feelings secret. As far as she knew, neither did D.J. In recent weeks, their relationship had changed, and it wasn’t clear when or how to share the news. ‘‘It’s your call,’’ she said to him in the lead-up to a meeting with his mother and older brother. ‘‘It’s your family. It’s up to you.’’ When she arrived at the house on Memorial Day in 2011, Anna didn’t know what D.J. planned to do. His brother, Wesley, was working in the garden, so she went straight inside to speak with D.J. and his mother, P. They chatted for a while at the dining table about D.J.’s plans for school and for getting his own apartment. Then there was a lull in the conversation after Wesley came back in, and Anna took hold of D.J.’s hand. ‘‘We have something to tell you,’’ they announced at last. ‘‘We’re in love.’’ ‘‘What do you mean, in love?’’ P. asked, the color draining from her face. To Wesley, she looked pale and weak, like ‘‘Caesar when he found out that Brutus betrayed him.’’ He felt sick to his stomach. What made them so uncomfortable was not that Anna was 41 and D.J. -

The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Naoki Higashida - Pdf Free Book

pdf The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice Of A Thirteen-Year-Old Boy With Autism Naoki Higashida - pdf free book Free Download The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Full Version Naoki Higashida, Naoki Higashida ebook The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism, Free Download The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Full Popular Naoki Higashida, The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Free Read Online, PDF Download The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Free Collection, Read Best Book Online The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism, Free Download The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Best Book, Read Online The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Book, Free Download The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Ebooks Naoki Higashida, by Naoki Higashida The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism, Naoki Higashida ebook The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism, The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism PDF Download, The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism Ebooks Free, free online The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism, Naoki Higashida ebook The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old -

Special Needs Library

USD #383 Autism & Special Needs Library Located at Eisenhower Middle School 800 Walters Drive, Manhattan, KS 66502 Helen Miller, Autism Coordinator 785-587-2880 2 The Autism Spectrum Disorders Library The special needs library provides information for parents and teachers on Autism Spectrum Disorders and a wide range of disabilities and issues related to various handicaps. To check out a book or video, fill out the card located in the back of the book (or on the back of the video) completely with name, date, and phone number or e-mail. Place the card in the black “check-out box” located on the shelf. All materials need to be returned within two months. When returning a book or video, replace the check-out card in the back of the book and cross off your name. The person checking out the book or video is responsible for the book. If, by whatever means an item is lost, please contact us and we will give you the replacement cost. 3 Books in the Library deal with the following topics: Autism & Asperger Syndrome Disabilities in General Learning Disabilities Physical & Mental Disabilities Stuttering Eating/Diets Video tapes Autism Spectrum Disorders Handbook for USD #383 4 A Title Author(s) Description A Is for Autism, F Is for Friend: A Joanna L. Keating- This upper elementary book touches on the importance of Kid’s Book on Making Friends with Velasco breaking down barriers to pave the way for unique a Child Who Has Autism friendships between kids who are not that different after all. The ABA Program Companion: J. -

Suffolk Libraries Books on Parenting

Autism and Asperger’s To reserve any of the below books from your nearest library please go to www.suffolklibraries.co.uk click on ‘Search and Reserve’ and type in the title of the book. Cover Title Author Description My brother is Louise Gorrod A booklet to help young siblings of different autistic children understand what autism is. National Autistic Society My sister is different Sarah Tamsin Talks about the ups and downs of life Hunter with a sister who has autism. This book is written and illustrated by ten-year- old Sarah who also has an autistic spectrum disorder. National Autistic Society I see things Pat Thomas Psychotherapist and counselor Pat differently : a first Thomas puts her gentle, yet look at autism straightforward approach to work in this new picture book aimed at helping children understand what autism is and how it affects someone who has it. -- Looking after Louis Lesley Ely This introduction to the issue of autism shows how - through imagination, kindness, and a special game of football - Louis's classmates find a way to join him in his world. Then they can include Louis in theirs. The reason I jump : Naoki Higashida, Written by Naoki Higishida when he one boy's voice Keiko Yoshida and was only 13, this remarkable book from the silence of David Mitchell explains the often baffling behaviour of autism autistic children and shows the way they think and feel - such as about the people around them, time and beauty, noise, and themselves. Naoki abundantly proves that autistic people do possess imagination, humour and empathy, but also makes clear, with great poignancy, how badly they need our compassion, patience and understanding.