Examining the Allure of the Fairytale Ballet Through Petipa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

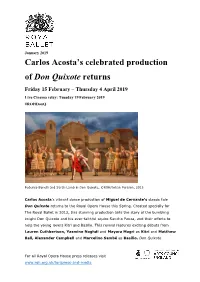

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

SWAN LAKE Dear Educators in the Winter Show of Oregon Ballet Theatre’S Student Performance Series (SPS) Students Will Be Treated to an Excerpt from Swan Lake

STUDENT PERFORMANCE SERIES STUDY GUIDE / Feburary 21, 2013 / Keller Auditorium / Noon - 1:00 pm, doors open at 11:30am SWAN LAKE Dear Educators In the winter show of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s Student Performance Series (SPS) students will be treated to an excerpt from Swan Lake. It is a quintessential ballet based on a heart-wrenching fable of true love heroically won and tragically Photo by Joni Kabana by Photo squandered. With virtuoso solos and an achingly beautiful score, it is emblematic of the opulent grandeur of the greatest of all 19th-Century story ballets. This study guide is designed to help teachers prepare students for their trip to the theatre where they will see Swan Lake Act III. In this Study Guide we will: • Provide the entire synopsis for Christopher Stowell’sSwan Lake, consider some of the stories that inspired the ballet, Principal Dancer Yuka Iino and Guest Artist Ruben Martin in Christopher and touch on its history Stowell’s Swan Lake. Photo by Blaine Truitt Covert. • Look closely at Act III • Learn some facts about the music for Swan Lake • Consider the way great dances are passed on to future generations and compare that to how students come to know other great works of art or literature • Describe some ballet vocabulary, steps and choreographic elements seen in Swan Lake • Include internet links to articles and video that will enhance learning At the theatre: • While seating takes place, the audience will enjoy a “behind the scenes” look at the scenic transformation of the stage • Oregon Ballet Theatre will perform Act III from Christopher Stowell’s Swan Lake where Odile’s evil double tricks the Prince into breaking his vow of love for the Swan Queen. -

ABSTRACTS Keywords: Ballet, Performance, Music, Musical

ABSTRACTS Yuri P. Burlaka PAQUITA GRAND PAS AND LE CORSAIRE GRAND PAS: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS The article explores the origin of creation and the production history of such masterpieces as Grand pas from Paquita and Grand pas Le Jardin Animé from Le Corsaire by Marius Petipa. The analysis proves the fact that with the invention of these choreographic structures the Romantic Pantomime Ballet turn into the Grand Ballet of the second half of the 19th century. In Petipa’s mature works the plot of the ballet is revealed not only in pantomime but through dance as well. Keywords: Marius Petipa, Paquita, Le Corsaire, history of Russian Ballet, ballet dramaturgy. Anna P. Grutsynova MOSCOW DON QUIXOTE: ON THE WAY TO ST. PETERSBURG The article is devoted to one of M. Petipa’s the most famous ballets called Don Quixote which was shown in Moscow and St. Petersburg versions in 1869 and 1871 respectively. The primary Moscow choreography is in a focus. Musical dramaturgy of the ballet is analyzed as well as connections between musical dramaturgy and drama plot are traced. Besides, the article contains a brief comparative analysis of music from Moscow and St. Petersburg choreographies of Don Quixote. Keywords: ballet, performance, music, musical dramaturgy, libretto, Don Quixote, M. Petipa, L. Minkus. Grafi ra N. Emelyanova P. TCHAIKOVSKY’S AND M. PETIPA’S THE SLEEPING BEAUTY IN K. SERGEYEV’S AND YU. GRIGOROVITCH’S VERSIONS The article is focused on preservation of the classical ballet heritage. An example of this theme is The Sleeping beauty ballet by M. Petipa and P. Tchaikovsky in K. -

Swan-Lake-Study-Guide-2017-18.Pdf

Swan Lake Study Guide 2017---18-18 Presented By the Department of Community Engagement Table of Contents The Quintessential Ballet 3 Milwaukee Ballet’s Swan Lake 4 Choreographic Birds of a Feather – Petipa, Ivanov & Pink 5 Did You Know? – Matthew Bourne 14 Behind the Music – Pyotr Tchaikovsky 15 Appendix A: Being A Good Audience Member 16 Sources and Special Thanks 17 2 The Quintessential Ballet Welcome to the Study Guide for Swan Lake , perhaps the world’s most widely recognized ballet aside from The Nutcracker . It has been called the “quintessential ballet” (quintessential means the purest and most perfect or the embodiment of, in this case, ballet!) and is often the show that pops into people’s minds when the word ballet is mentioned. Since its premiere in Moscow, Russia, it has been presented in over 150 versions by more than 100 companies in at least 25 different countries. That’s a lot of swans! Swan Lake didn’t start out successfully – which is surprising, considering its fame today. It premiered on February 20, 1877, and although Tchaikovsky’s spectacular music was used from the beginning, the choreography, originally done by Julius Reisinger, was less than stellar. A critic who was at the performance wrote, "Mr. Reisinger’s dances are weak in the extreme.... Incoherent waving of the legs that continued through the course of four hours - is this not torture? The corps de ballet stamp up and down in the same place, waving their arms like a windmill’s vanes - and the soloists jump about the stage in gymnastic steps." Ouch! Unfortunately Reisinger failed to mesh his choreography with the psychological, beautiful music Tchaikovsky created. -

Coppelia-Teacher-Resource-Guide.Pdf

Teacher’s Handbook 1 Edited by: Carol Meeder – Director of Arts Education February 2006 Cover Photo: Jennifer Langenstein – Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Principal Dancer Aaron Ingley – Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Corps de Ballet Dancer Ric Evans – Photographer 2 Introduction Dear Educator, We have often thanked you, the academic community and educators of our children, for being partners with us in Arts Education. We have confirmed how the arts bring beauty, excitement, and insight into the experience of everyday living. Those of us who pursue the arts as the work of our lives would find the world a dark place without them. We have also seen, in a mirror image from the stage, how the arts bring light, joy, and sparkle into the eyes and the lives of children and adults in all walks of life. Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre strives not only to entertain but to demonstrate the significance and importance of presenting our art in the context of past history, present living, and vision for the future. In this quest we present traditional ballets based on classic stories revered for centuries, such as Coppelia and Cinderella; and contemporary ballets by artists who are living, working, and creating everyday, such as our jazz program Indigo In Motion and the premiers we have done to the music of Sting, Bruce Springsteen, and Paul Simon. In this way we propel our art into the future, creating new classics that subsequent generations will call traditional. It is necessary to see and experience both, past and present. It enhances our life and stirs new ideas. We have to experience where we came from in order to develop a clear vision of where we want to go. -

Soirée Petipa Vignette De Couverture Marins Petipa

Soirée Petipa Vignette de couverture Marins Petipa. Opéra de Bordeaux DE/J_ BORDEAUX SOIREE PETIPA Ballet de l'Opéra de Bordeaux Paquita (grand pas) Huit danseuses : Nathalie Anglard, Silvie Daverat, Sophie Guyomard, Stefania Sandrin, Barbara Vignaud, Carole Dion, Corba Mathieu, Maud Rivière Couples : Céline Da Costa, Petulia Chirpaz Hélène Ballon, Celia Millan Viviana Franciosi, Sandrine Gouny Première Variation : Emmanuelle Grizot Deuxième Variation : Aline Bellardi Troisième Variation : Christelle Lara Quatrième Variation : Sandra Macé Raymonda (J*™ acte) Czardas Solistes : Viviana Franciosi Giuseppe Delia Monica (24, 25, 29 avril), Gilles Martin (27, 28 avril) Couples : Petulia Chirpaz, Céline Da Costa, Maud Rivière (24, 25, 29 avril), Corba Mathieu (27, 28 avril), Carole Dion, Sandrine Gouny, Chantai Perpignan, Stefania Sandrin, Sophie Guyomard Gilles Martin ou Giuseppe Delia Monica, Salvatore Gagliardi, Johannes Haider, Alexis Malovik, Christophe Nicita, Omar Taïebi, Sébastien Riou, Emiliano Piccoli Première Variation (variation d'Henriette) : Christelle Lara Deuxième Variation (variation de Clémence) : (24, 25, 29 avril) : Emmanuelle Grizot, Silvie Daverat, Barbara Vignaud (27, 28 avril) : Sandra Macé, Celia Millan, Hélène Ballon Pas de dix Nathalie Anglard, Hélène Ballon, Aline Bellardi, Barbara Vignaud Brice Bardot, Jean-Jacques Herment, Konstantin Inozemtzev, Gregory Milan Opéra de Bordeaux Ballet de l'Opéra de Bordeaux Directeur artistique : Charles Jude Soirée Petipa Paquita (grand pas) Don Quichotte (pas de deux du 3ème acte) -

Petipa, Who Has Been Gaining Renewed Interest in France Over the Last Three Years from French Researchers, Remains a Bedrock and a Driving Force.” —LE MONDE

NEW THIS SPRING! “More relevant than ever, Marius Petipa, who has been gaining renewed interest in France over the last three years from French researchers, remains a bedrock and a driving force.” —LE MONDE “Gazes at Petipa’s life and work through the social and political contexts in which he created, and opens the door to questions about how and why those works resonate with contemporary audiences.” —ARTS INTERCEPT Marius Petipa was an unlikely artistic revolutionary. A middling dancer, he bounced around European cultural centers until he finally washed up in St. Petersburg in 1847 at age 29 – hired, sight unseen, by the Imperial Ballet as a principal dancer. A skilled socialite, he curried favor with the right people and within a decade staged his first ballet: the massive epic The Pharaoh’s Daughter. MARIUS PETIPA: THE FRENCH MASTER OF RUSSIAN BALLET traces Petipa’s career from his early, crowd-pleasing choreography to the works “Very good…full of visual interest.” that would become his masterpieces: Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake. —RODNEY EDGECOMBE, PHD., UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN Their stunning choreography and Tchaikovsky’s music elevated ballet for the first time to one of the world’s great art forms. STANDOUT FILM FIPADOC 2019, BIARRITZ (FRANCE) The film features stunning performance and rehearsal footage, along with intriguing period artwork and colorized photography. Once celebrated, MARIUS PETIPA: THE FRENCH MASTER OF RUSSIAN BALLET Petipa’s name has been largely forgotten outside of ballet. MARIUS A film by Denis Sneguirev • An Icarus Films Release PETIPA makes a significant contribution in re-introducing us to the life 2019 • 52 min • Color • French, Russian, English and Italian w/ English subtitles • Not Rated and work of this central figure. -

Concerto Enigma Variations Raymonda Act III Press Release

August 2019 The Royal Ballet presents Concerto, Enigma Variations and Raymonda Act III 22 October – 20 December 2019 | #ROHconcertomixed | Tickets £3 - £75 Concerto. Artists of The Royal Ballet. ©ROH, 2012. Ph. Bill Cooper. The first mixed programme of the 2019/20 Season highlights the versatility of The Royal Ballet Works by Kenneth MacMillan, Frederick Ashton and Rudolf Nureyev ROH Live Cinema Tuesday 5 November This October, The Royal Ballet showcases the work of leading 20th-century choreographers Kenneth MacMillan and Frederick Ashton alongside Rudolf Nureyev’s production of an Imperial classic in a mixed programme that celebrates the versatility of the Company. For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media Concerto, created by Kenneth MacMillan in 1966 for Berlin’s Deutsche Oper Ballet, is set to Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto no.2 in F and includes energetic corps de ballet sections as well as lyrical pas de deux that perfectly reflect the contrasting mood of the music. Bright, vivid designs by Jürgen Rose encapsulate the work’s warmth and energy and Concerto remains one of MacMillan’s most celebrated lyrical creations. Frederick Ashton’s Enigma Variations is also presented as part of this programme. It received its premiere at the Royal Opera House more than fifty years ago, and last performed at Covent Garden in 2011, the ballet features period designs by Julia Trevelyan Oman and Edward Elgar’s eponymous score, illustrating an imagined gathering of the composer and his companions. This revival will feature debuts from Royal Ballet Principals Laura Morera, Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball. -

Cesare Pugni: KONIOK GORBUNOK, ILI TSAR-DEVITSA Le Petit Cheval Bossu, Ou La Tsar-Demoiselle the Little Humpbacked Horse, Or the Tsar-Maiden

Cesare Pugni: KONIOK GORBUNOK, ILI TSAR-DEVITSA Le Petit Cheval bossu, ou La Tsar-Demoiselle The Little Humpbacked Horse, or The Tsar-Maiden Cesare Pugni: KONIOK GORBUNOK, ILI TSAR-DEVITSA Le Petit Cheval bossu, ou La Tsar-Demoiselle The Little Humpbacked Horse, or The Tsar-Maiden A Magical Ballet in 4 Acts and 7 Scenes Scenario and Choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon after Petr Pavlovich Yershov Music by Cesare Pugni Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: KONIOK GORBUNOK, ILI TSAR-DEVITSA Le Petit Cheval bossu, ou La Tsar-Demoiselle The Little Humpbacked Horse, or The Tsar-Maiden Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3568-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3568-8 Cesare Pugni in St Petersburg. A photograph from 1868 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................................. ix No. 1 Introduction.........................................................................................................2 -

WORLD PREMIERE of Raymonda by Tamara Rojo London Coliseum 13 - 23 January 2022 Ballet.Org.Uk/Raymonda

English National Ballet WORLD PREMIERE of Raymonda by Tamara Rojo London Coliseum 13 - 23 January 2022 ballet.org.uk/raymonda The eagerly awaited world premiere of Raymonda by English National Ballet’s Artistic Director Tamara Rojo CBE, after Marius Petipa, will take place at the London Coliseum from 13 - 23 January 2022. Marking her debut in choreography and direction, Rojo adapts this 19th-century classic for today’s audiences, revisiting this important but rarely performed work of the ballet canon which is not, in its entirety, in any other UK dance companies’ repertoire. Bringing the story into the setting of the Crimean war and drawing inspiration from the groundbreaking spirit and work of the women supporting the war effort, including Florence Nightingale, Raymonda is recast as a young woman with a calling to become a nurse. With a new narrative and developed characterisation bringing women’s voices to the fore, Rojo’s Raymonda introduces a heroine in command of her own destiny. Tamara Rojo said: “It continues to be a part of my vision for English National Ballet to look at classics with fresh eyes, to make them relevant, find new contexts, amplify new voices and ultimately evolve the art form. I have truly enjoyed delving into the creative process of adapting and choreographing a large-scale ballet. “Raymonda is a beautiful ballet – extraordinary music, exquisite and intricate original choreography – with a female lead who I felt deserved more of a voice, more agency in her own story. Working with my incredible creative team, I have set Raymonda in a new historical context, adapting the narrative in order to bring something unique, relevant and inspiring to our audiences. -

LA BAYADÈRE the Grand Romantic Ballet Set in India, Featuring Spectacular Sets and Virtuoso Performances

PRESS RELEASE LA BAYADÈRE The grand Romantic ballet set in India, featuring spectacular sets and virtuoso performances. The Czech National Ballet is preparing the premiere of a new version of LA BAYADÈRE. The famous late-Romantic ballet to Ludwig Minkus’s music, telling the story of a beautiful Indian temple dancer, characterised by exquisite sets and replete with virtuoso performances, has been frequently staged at leading dance venues worldwide and hence is now becoming part of our company’s repertoire too. The story of ill-fated love, featuring spectacular sets and colourful costumes, is a real treat for those with a penchant for grand classical works, as well as a great challenge for the Czech National Ballet itself. A new version of La Bayadère is being prepared by the Mexican choreographer Javier Torres and his staging team, already familiar to Czech audiences from the highly acclaimed and popular production of The Sleeping Beauty. ‘Dramatic stories in which a tragic earthly love is lost by death and then redeemed in a spiritual world were particularly fashionable in Petipa’s era because they followed the ideal of unreachable love that characterised the Romantic period. It was also popular to set these stories in faraway lands little known by the audiences because it added a touch of the exotic and mystery. It is evident that to those audiences it was more appealing to see a serious yet sensual production that involved temple dancers than one with western nuns. Moreover, the lack of common knowledge about these faraway cultures gave the artists of the period the liberty to produce works in fairy-tale fashion without worrying if some aspects in them would be completely illogical. -

Le Corsaire Press Release

Gainesville Ballet Contact: Elysabeth Muscat 7528 Old Linton Hall Road [email protected] Gainesville, VA 20155 703-753-5005 www.gainesvilleballetcompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 14, 2014 LE CORSAIRE, ACT III IS FOURTH DEBUT IN GAINESVILLE BALLET REPERTORY GAINESVILLE, Va. – Gainesville Ballet is pleased to perform Le Corsaire, Act III and a Spring Recital at the elegant opera house of the 1,123-seat Merchant Hall at the Hylton Performing Arts Center on Saturday, June 7, 2014 at 6:30 PM. The production will feature international faculty and students of the award-winning arts organization. On the very same 100-foot stage, Gainesville Ballet was recognized by the Prince William County Arts Council as Outstanding Arts Organization during the 2012 Seefeldt Awards for Arts Excellence. For the third consecutive spring season, Gainesville Ballet will proactively build its dance repertory. In addition to annual Nutcracker performances, the school brought an inaugural spring production to the Gainesville Ballet at the Hylton Performing Arts Center A traditional Nutcracker story – November 2013 performing arts community with Coppélia in 2012; Swan Snowflakes, Act I with international guest stars Nour Eldesouki (Nutcracker Prince) and Carolina Boscan (Clara Princess) Lake, Act II in 2013; and Le Corsaire, Act III in 2014. Gainesville Ballet will now present Le Corsaire, Act III for the first time, as the Company and School build a strong repertory of four classical ballets: Nutcracker, Coppélia, Swan Lake and Le Corsaire. Even though Le Corsaire is new to the formal body of artistic works at Gainesville Ballet, the faculty and students already bring a wide range of role experiences and formal recognition to the stage.