CCI Newsleter Feb 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Mahuya Hom Choudhury Scientist-C

Dr. Mahuya Hom Choudhury Scientist-C Patent Information Centre-Kolkata . The first State level facility in India to provide Patent related service was set up in Kolkata in collaboration with PFC-TIFAC, DST-GoI . Inaugurated in September 1997 . PIC-Kolkata stepped in the 4th plan period during 2012-13. “Patent system added the fuel to the fire of genius”-Abrham Lincoln Our Objective Nurture Invention Grass Root Innovation Patent Search Services A geographical indication is a sign used on goods that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that place of origin. Three G.I Certificate received G.I-111, Lakshmanbhog G.I-112, Khirsapati (Himsagar) G.I 113 ( Fazli) G.I Textile project at a glance Patent Information Centre Winding Weaving G.I Certificate received Glimpses of Santipore Saree Baluchari and Dhanekhali Registered in G.I registrar Registered G.I Certificates Baluchari G.I -173-Baluchari Dhanekhali G.I -173-Dhaniakhali Facilitate Filing of Joynagar Moa (G.I-381) Filed 5 G.I . Bardhaman Mihidana . Bardhaman Sitabhog . Banglar Rasogolla . Gobindabhog Rice . Tulaipanji Rice Badshah Bhog Nadia District South 24 Parganas Dudheswar District South 24 Chamormoni ParganasDistrict South 24 Kanakchur ParganasDistrict Radhunipagol Hooghly District Kalma Hooghly District Kerela Sundari Purulia District Kalonunia Jalpaiguri District FOOD PRODUCTS Food Rasogolla All over West Bengal Sarpuria ( Krishnanagar, Nadia Sweet) District. Sarbhaja Krishnanagar, Nadia (Sweet) District Nalen gur All over West Bengal Sandesh Bardhaman Mihidana Bardhaman &Sitabhog 1 Handicraft Krishnanagar, Nadia Clay doll Dist. Panchmura, Bishnupur, Terrakota Bankura Dist. Chorida, Baghmundi 2 Chhow Musk Purulia Dist. -

Micro Finance SHG Wise Utilisation Report from 01.08.16 to 28.12.2016

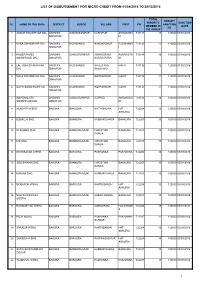

LIST OF DISBURSEMENT FOR MICRO CREDIT FROM 01/08/2016 TO 28/12/2016 TOTAL AMOUNT MINORITY SANCTION SL. NAME OF THE SHGs DISTRICT BLOCK VILLAGE POST PIN SANCTION MEMBER IN DATE ED THE GROUP 1 ANKUR SWANIRVAR DAL DAKSHIN GANGARAMPUR KASHIPUR ASHOKGRA 733141 13 130000 03/08/2016 DINAJPUR M 2 DANA SWANIRVAR DAL DAKSHIN KUSHMANDI NANDAPUKUR KUSHMAND 733132 12 120000 03/08/2016 DINAJPUR I 3 KHODA HAFEJ DAKSHIN GANGARAMPUR ASHAKGRAM ASHAKGRA 733141 10 100000 03/08/2016 SWANIRVOR DAL DINAJPUR DARIYA PARA M 4 LAL JABA SWANIRVAR DAKSHIN KUSHMANDI BATESHWA NAHIT 733132 12 120000 03/08/2016 DAL DINAJPUR (MALIHAR) 5 MALA SWANIRVAR DAL DAKSHIN KUSHMANDI BOTESHWAR NAHIT 733132 11 110000 03/08/2016 DINAJPUR 6 SATHI SWANIRVAR DAL DAKSHIN KUSHMANDI BOTESHWAR NAHIT 733132 11 110000 03/08/2016 DINAJPUR 7 SWARNALATA DAKSHIN GANGARAMPUR RAYPUR ASHOKGRA 733141 10 100000 03/08/2016 SWANIRVAR DAL DINAJPUR M 8 ABADATH WSHG BAKURA BARJORA HAT ASHURIA HAT 722204 12 120000 05/08/2016 ASHURIA 9 BISMILLA SHG BAKURA BANKURA KABBAR DANGA BANKURA 722201 10 100000 05/08/2016 10 BLASHING SHG BAKURA BANKURA MUNI CHRISTIAN BANKURA 722101 10 100000 05/08/2016 DANGA 11 DIP SHG BAKURA BANKURA MUNI CHRISTIAN BANKURA 722101 10 100000 05/08/2016 DANGA 12 ID MOBARAK WSHG BAKURA BARJORA PAKHANNA PAKHANNA 722204 14 140000 05/08/2016 13 JISU SWAHAI SHG BAKURA BANKURA CHRISTIAN BANKURA 722201 10 100000 05/08/2016 DANGA 14 MADINA SHG BAKURA BANKURA MUNI KABBAR DANGA BANKURA 722101 10 100000 05/08/2016 15 MOBAROK WSHG BAKURA BARJORA KANTA BANDH HAT 722204 12 120000 05/08/2016 ASHURIA -

Introduction History of Bengal

Introduction West Bengal is one of the thirty-seven constituent states/ Union Territories of the Union of India lying on the eastern region of the country. India's total landmass is divided into 28 states and 9 union territories. Until 6 August 2019, there were officially 29 states in India. However, that number now has decreased by one to make 28 states after Jammu & Kashmir was granted the status of a Union Territory with its own legislature. It is the 4th ranked state in percentage share of 7.79 to total population of India and also the seventh most populous of the sub-national entity of the world, with over 91 million inhabitants covering a total area of 88,752 sq. km3. West Bengal is one of the most thickly populated states with population density of 1028 per sq. km. The striking point is that with 2.70 percent land share of the country it sustains 7.55 per cent of its population, ranks 12th in area but 4th in population share. A major agricultural producer, West Bengal is the 6th largest contributor to India’s net domestic product. It is bordered by the five national boundaries of Orissa, Jharkhand and Bihar on the west, Sikkim on the north and Assam on the east. It has international borders with the neighbouring countries – Bhutan and Nepal on the north and Bangladesh on the east. History of Bengal Bengal finds a place even in prehistoric times. Stone-age tools have been excavated in the state dating back 20,000 years. Remains of civilization in the greater Bengal region date back 4,000 years. -

Registration Details of Geographical Indications

REGISTRATION DETAILS OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS Goods S. Application Geographical Indications (As per Sec 2 (f) State No No. of GI Act 1999 ) FROM APRIL 2004 – MARCH 2005 Darjeeling Tea (word & 1 1 & 2 Agricultural West Bengal logo) 2 3 Aranmula Kannadi Handicraft Kerala 3 4 Pochampalli Ikat Handicraft Telangana FROM APRIL 2005 – MARCH 2006 4 5 Salem Fabric Handicraft Tamil Nadu 5 7 Chanderi Sarees Handicraft Madhya Pradesh 6 8 Solapur Chaddar Handicraft Maharashtra 7 9 Solapur Terry Towel Handicraft Maharashtra 8 10 Kotpad Handloom fabric Handicraft Odisha 9 11 Mysore Silk Handicraft Karnataka 10 12 Kota Doria Handicraft Rajasthan 11 13 & 18 Mysore Agarbathi Manufactured Karnataka 12 15 Kancheepuram Silk Handicraft Tamil Nadu 13 16 Bhavani Jamakkalam Handicraft Tamil Nadu 14 19 Kullu Shawl Handicraft Himachal Pradesh 15 20 Bidriware Handicraft Karnataka 16 21 Madurai Sungudi Handicraft Tamil Nadu 17 22 Orissa Ikat Handicraft Odisha 18 23 Channapatna Toys & Dolls Handicraft Karnataka 19 24 Mysore Rosewood Inlay Handicraft Karnataka 20 25 Kangra Tea Agricultural Himachal Pradesh 21 26 Coimbatore Wet Grinder Manufactured Tamil Nadu 22 28 Srikalahasthi Kalamkari Handicraft Andhra Pradesh 23 29 Mysore Sandalwood Oil Manufactured Karnataka 24 30 Mysore Sandal soap Manufactured Karnataka 25 31 Kasuti Embroidery Handicraft Karnataka Mysore Traditional 26 32 Handicraft Karnataka Paintings 27 33 Coorg Orange Agricultural Karnataka 1 FROM APRIL 2006 – MARCH 2007 28 34 Mysore Betel leaf Agricultural Karnataka 29 35 Nanjanagud Banana Agricultural -

Heritage, Culture & Identity Re-Negotiating Spaces of Memory

Seminar Brochure ICSSR Sponsored Two-Day Interdisciplinary International Seminar Organised by Sarat Centenary College in Collaboration with West Bengal Heritage Commission 20 & 21 January 2020 Heritage, Culture & Identity Re-Negotiating Spaces of Memory in a Time of Rapid Urbanisation ICSSR Sponsored Two-Day Interdisciplinary International Seminar Organised by Sarat Centenary College in Collaboration with West Bengal Heritage Commission on Heritage, Culture & Identity Re-Negotiating Spaces of Memory in a Time of Rapid Urbanisation 20 & 21 January 2020 Seminar Organising Core Committee Patron: Janab Md. Hanif, President, Governing Body, Sarat Centenary College Chairperson: Dr Sandip Kumar Basak, Principal, Sarat Centenary College [email protected] Convenor: Dr Ramanuj Konar, Assistant Professor, IQAC Coordinator, Sarat Centenary College; Editor, postScriptum <postscriptum.co.in> [email protected] Co-Convenor: Dr Basudeb Malik, Officer on Special Duty, West Bengal Heritage Commission, Govt. of WB [email protected] Treasurer: Prof. Basudev Halder, Assistant Professor, Bursar, Sarat Centenary College [email protected] Asstt. Treasurer: Shri Shyamal Bhattacharya, Accountant, Sarat Centenary College [email protected] This open access seminar brochure is published by The Principal <[email protected]>, Sarat Centenary College <sccollegednk.ac.in>, at Dhaniakhali on 20 January 2020 Concept & Design: Dr Ramanuj Konar Seminar Brochure 1 International Seminar Sarat Centenary College 20 & 21 January 2020 Concept Note of the Seminar Since the 1990s, after the effects of Globalisation started spreading all over, the process of urbanisation has entered rapid stage of acceleration. As per global data, 54% of total global population was living in urban areas in 2014 and it is projected that by the year 2050 the figure will reach 66%. -

Innovative Practices of Economics Department

List of Seminars/ Workshops/ Talks organized by Seminar Committee in Collaboration with Different Departments and Committees 2014-2019 Sl Resource person (if any)/ any Date Topic No. other relevant information 1 13.2.19 Talk on Sino Indian Relationship ( by Political Prof Ishani Naskar, Profsor, Science Department) Department of pol Science, Rabindra Bharati Unversity 2 8.2.19 Workshop on Mathematics for All sponsored Dr. Supriya Mukherjee, by with WB State Council of Science and Gurudas College Technology in collaboration with Netaji Dr. Debashish Burman, Subhas Engineering College ( By Mathematics Netaji Sunhas Engineering Department) College Debprasead Majumder, Narkeldanga High School For Boys 3 22.2.19 How Long to Stay? Winter Foraging Decision Mr. Abhirup Khara, Msc of a Mountan Unregulate (By Zoology Research Affliate at NCF Department) 4 27.09.18 Lecture on “Greek Tragedy”. Prof. Mousumi Mandal (Presidency University) 5. 12.10.2018 Lecture on “Immune surveillance in cancer: Prof, Ellora Sen, Scientist Therapeutic implications” ( By Zoology VI & Professor, Department) National Brain Research Centre, Manesar, 122 052, Haryana, India 6 12.10.2018 Pubertal Metabolic and Endocrine changes: Dr. Pratip Chakraborty Path to Adolescent Polycystic Ovary Symdrome and unexplained pregnancy 7. 21.02.19 Lecture on “Staying On: Shakespeare and the Dr. Priyanka Basu (British Legacies of Theatre in the East (1930-1980). ( Library, London/School of By English Department) Oriental and African Studies) 8. 7.5.19 Practical Significance of Sociology (By Prof Angana Dutta Sociology Department) Assistant Professor, Jogesh Chandra College 18.3.19 Advaita Vdanta in Everyday Life Dr. Pritam Ghoshal, JU 9. Gita In our Every day Life (By Philosophy Taraknath Adhikary, Department and Sanskrit Department) Rabindra Bharati University 1.4.19 Lecture on “Gandhi’s notion of education: Its Prof. -

REGISTRATION DETAILS of G.I APPLICATIONS 15Th September, 2003 – Till Date

STATE WISE REGISTRATION DETAILS OF G.I APPLICATIONS th 15 September, 2003 – Till Date Goods S. Application Geographical Indications (As per Sec 2 (f) of State No No. GI Act 1999 ) FROM APRIL 2004 – MARCH 2005 1 1 & 2 Darjeeling Tea (word & logo) Agricultural West Bengal 2 3 Aranmula Kannadi Handicraft Kerala 3 4 Pochampalli Ikat Handicraft Andhra Pradesh FROM APRIL 2005 – MARCH 2006 4 5 Salem Fabric Handicraft Tamil Nadu 5 7 Chanderi Fabric Handicraft Madhya Pradesh 6 8 Solapur Chaddar Handicraft Maharashtra 7 9 Solapur Terry Towel Handicraft Maharashtra 8 10 Kotpad Handloom fabric Handicraft Odisha 9 11 Mysore Silk Handicraft Karnataka 10 12 Kota Doria Handicraft Rajasthan 11 13 & 18 Mysore Agarbathi Manufactured Karnataka 12 15 Kancheepuram Silk Handicraft Tamil Nadu 13 16 Bhavani Jamakkalam Handicraft Tamil Nadu Himachal 14 19 Kullu Shawl Handicraft Pradesh 15 20 Bidriware Handicraft Karnataka 16 21 Madurai Sungudi Handicraft Tamil Nadu 17 22 Orissa Ikat Handicraft Odisha 18 23 Channapatna Toys & Dolls Handicraft Karnataka 19 24 Mysore Rosewood Inlay Handicraft Karnataka Himachal 20 25 Kangra Tea Agricultural Pradesh 21 26 Coimbatore Wet Grinder Manufactured Tamil Nadu 22 28 Srikalahasthi Kalamkari Handicraft Andhra Pradesh 23 29 Mysore Sandalwood Oil Manufactured Karnataka 24 30 Mysore Sandal soap Manufactured Karnataka 25 31 Kasuti Embroidery Handicraft Karnataka 26 32 Mysore Traditional Paintings Handicraft Karnataka 27 33 Coorg Orange Agricultural Karnataka 1 FROM APRIL 2006 – MARCH 2007 28 34 Mysore Betel leaf Agricultural Karnataka -

Annual Report (2015-16)

ANNUAL REPORT (201(2015555----16161616)))) DIRECTORATE OF TEXTILES (Handlooms, Spinning Mills, Silk Weaving & Handloom Based Handicrafts Division, West Bengal) Annual Report 2015-16 Page 1 ACTIVITIES & PERFORMANCE OF THE DIRECTORATE OF TEXTILES, HANDLOOMS. SPINNING MILLS, SILK WEAVING & HANDLOOM BASED HANDRICRAFTS DIVISION. INTRODUCTION The Directorate of Textiles (Handloom, Spinning Mills, Silk weaving & Handloom Based Handicrafts Division) under MSME & T Department, West Bengal is the nodal Agency to look after the development of Handloom Sector in the State of West Bengal and also Powerloom, Hosiery and Readymade Garment Industries in West Bengal. Some Basic Statistics Handloom Industry is the largest cottage industry of the State providing employment opportunities to a large number of people only next to Agriculture. In West Bengal, there are 3,07,829 handlooms as per census conducted by the Ministry of Textiles, Govt. of India in 2009-2010 giving direct and indirect employment to about 6,65,006 persons. 1 No. of Handloom workers as per census of GOI, 2009-10 6,65,006 2 No. of household units engages in handloom activities 4,06,761 3 No. of Active PWCS 526 4 Annual Production (in million Sq. Meter) 769 5 Weavers’ Photo Identity Cards issued 5,31,075 BENGAL HANDLOOM PRODUCTS Fine Cotton Variety (80’ s -100’ s) Super fine “MUSLIN” a.Tangail & Jamdani Saree made of Dyes b.Shantipuri Saree Exquisite variety c.Dhaniakhali Saree Hand Spun a.Baluchari Saree a.Synthetic Cotton Yarn b. Natural d. Lungi & b.Korial saree e.Dhoti c.Silk Tangail & Jamdani Saree Waste Silk a.Ketis b.Noil Medium/ Coarse c.Matka Cotton Variety BENGAL d.Ghicha Silk a.Sarees Variety HANDLO OM Cotton b.Shirting MOMS variety c.Lungi d.Curtain e.Bed cover/Sheet Plan Than EXPORT VARIETY f.Mosquito net etc. -

List of Contents

1 List of Contents List of Contents 2 List of Abbreviations 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Purpose of the Study 6 Aims and Objectives 6 Rationale for Selection of the Geography for the Study 6 3. Methodology 10 Approach and Limitations 10 Sampling 10 Tool Development 10 Data Collection 13 Analysis 14 4. Topline Findings/Key Observations 15 5. All India Findings 17 Demographics 17 Central Sector Schemes 18 Centrally Sponsored Schemes 25 Access and Uptake 26 Problems with Uptake 26 Time Taken 27 Access Support 29 6. Detailed Findings: Gujarat 31 Demographics 31 State Level Schemes 33 Social Security 33 Financial Assistance 34 Capacity Building and Other Support 39 Access and Uptake of Other Schemes 44 Demographics 45 State Level Schemes 47 Social Security 47 Financial Assistance 49 Capacity Building and other Support 53 Access and Uptake of Other Schemes 67 8. Detailed Findings: Rajasthan 68 2 Demographics 68 State Level Schemes 70 Social Security 70 Financial Assistance 72 Capacity Building and Other Support 72 Access and Uptake of Other Schemes 83 9. Detailed Findings: Uttar Pradesh (UP) 84 Demographics 84 State Level Schemes 86 Social Security 86 Financial Assistance 88 Capacity Building and Other Support 90 Access and Uptake of Other Schemes 107 10. Detailed Findings: West Bengal (WB) 108 Demographics 108 State Level Schemes 110 Social Security 110 Financial Assistance 111 Capacity Building and Other Support 112 Access and Uptake of Other Schemes 117 12. Trends and Patterns 120 13. Recommendations 121 14. Conclusion 123 Glossary 124 ANNEXURE -

Garments (Textiles, Readymade Garments, Woolen, Hosiery & Knitwears)

JC Groups Garments (Textiles, Readymade Garments, Woolen, Hosiery & Knitwears) JC Groups Kids Boys Clothing For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Kids Girls Clothing For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Mens Wear Shirts For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. T-shirts For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Winter wear Denims For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Ethnic Wear Trousers For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Suits & Blazers Track Wear and Rain wear For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Inner Wear & Sleepwear Clothing accessories For complete design E.mail us and you shall send your own design also. Saree Different Type of Sarees Available:- for current design Email us for catalogue. Assam Silk Saree Sambalpuri Saree Banarasi Silk saree Sambalpuri or ‗Ikat‘ is the pride of Odisha. This pure Bandhani/Bandhej Saree handloom sarees is available in cotton, silk, and Baluchari Saree Taussor. Bhagalpuri Saree Tant – Cotton sari from Bengal Bomkai Sarees Chanderi sari– Madhya Pradesh Chanderi Saree Maheshwari – Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh Dhakai Saree Kosa silk – Chhattisgarh Kalamkari Saree Dhokra silk – Madhya Pradesh Kantha Saree Jamdani sari of Bangladesh. Kanchipuram silk Saree Taant sari – throughout Bengal Kota Saree Tashore silk saree – Maldah, West Bengal Konrad Saree—Tamil nadu Baluchari sari – Bishnupur, West Bengal Leheriya Saree Murshidabad silk – Murshidabad, West Bengal Paithani Saree Dhaniakhali cotton – Dhaniakhali, West Bengal Patola Saree Kaantha sari – throughout Bengal Garode / Korial – Murshidabad, West Bengal Mysore silk – Karnataka Shantipuri cotton – Shantipur, West Bengal Mysore silk saree with golden zari. -

(Handlooms, Spinning Mills, Silk Weaving & Handloom Based

2016-17 GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL. Directorate of Textiles, (Handlooms, Spinning Mills, Silk weaving & Handloom Based Handicrafts Division.) & (Powerloom, Hosiery & Readymade Garments Division) Activities & Performance Of The Directorate Of Textiles, Handlooms. Spinning Mills, Silk Weaving & Handloom Based Handricrafts Division. INTRODUCTION The Directorate of Textiles (Handloom, Spinning Mills, Silk weaving & Handloom Based Handicrafts Division) under IC& E Department, West Bengal is the nodal Agency to look after the development of Handloom Sector in the State of West Bengal . Other organisations and undertakings, which support the development of Handloom sector of the State, include two Central marketing organisations and State controlled spinning mills. The central marketing organizations are; (1) The West Bengal State Handloom Weavers’ Cooperative Society Ltd.(TANTUJA) (2) Paschim Banga Resham Silpi Samabay Mahasangha Ltd. ((RESHAM SILPI), They procure handloom cloth from primary weavers’ coop. societies and also from weavers outside cooperative fold and sell their product from their retail outlets. Some Basic Statistics Handloom Industry is the largest cottage industry of the State providing employment opportunities to a large number of people only next to Agriculture. In West Bengal, there are 3,07,829 handlooms as per census conducted by the Ministry of Textiles, Govt. of India in 2009-2010 giving direct and indirect employment to about 6,65,006 persons. The 4 th Handloom census is going on. 1 No. of Handloom workers as per census of GOI, 2009-10 6,65,006 2 No. of household units engages in handloom activities 4,06,761 3 No. of Active PWCS 528 4 Annual Production (in million Sq. Meter) 715.00 5 Weavers’ Photo Identity Cards issued 5,31,075 BENGAL HANDLOOM PRODUCTS Fine Cotton Variety (80’ s -100’ s) Exquisite variety a.Tangail & Jamdani Saree Super fine “MUSLIN” a.Baluchari b.Shantipuri Saree made of Hand Spun Saree c.Dhaniakhali Saree Cotton Yarn b.Korial saree d. -

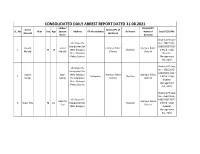

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 31.08.2021 Father/ District/PC Name District/PC of SL

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 31.08.2021 Father/ District/PC Name District/PC of SL. No Alias Sex Age Spouse Address PS of residence Ps Name Name of Case/ GDE Ref. Accused residence Name Accused Chakulia PS Case Vill-Sripur PS- No : 258/21 US- GoalpokharDist- 188/269/270/27 Kousik Gokul Islampur Police Islampur Police 1 M 18 Uttar Dinajpur, Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) Mondal Mandal District District Dist.: Islampur Disaster Police District Management Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case Vill-Sripur PS- No : 258/21 US- GoalpokharDist- 188/269/270/27 Nripen Jatin Uttar Dinajpur, Islampur Police Islampur Police 2 Goalpukur Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) Sarkar Sarkar PS: Goalpukur District District Disaster Dist.: Islampur Management Police District Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case No : 258/21 US- Vill-Sripur PS- 188/269/270/27 Dabrata Islampur Police 3 Sujan Roy M 21 GoalpokharDist- Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) Roy District Uttar Dinajpur, Disaster Management Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case No : 258/21 US- Vill- Kakaharwa 188/269/270/27 Shahid Islampur Police 4 Rofad M 31 PS- Baisidist- Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) Hussain District Purnia (Bihar) Disaster Management Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case No : 258/21 US- 188/269/270/27 Md. Islampur Police 5 Abuzar Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) Golam District Disaster Management Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case No : 258/21 US- Vill- Kakaharwa 188/269/270/27 Md. Islampur Police 6 Kaisar 18 PS- Baisidist- Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) Mohisin District Purnia (Bihar) Disaster Management Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case No : 258/21 US- Vill- Kakaharwa 188/269/270/27 Islampur Police 7 Nashir M 20 Mahabub PS- Baisidist- Chakulia 1 IPC & 51(b) District Purnia (Bihar) Disaster Management Act, 2005 Chakulia PS Case No : 258/21 US- Vill- Kakaharwa 188/269/270/27 Islampur Police 8 Basik M 31 Md.