Chasing Reporters: Infotainment, Intertextuality and Media Satire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

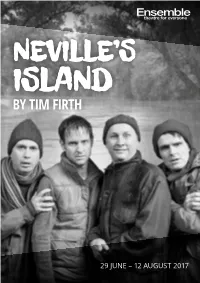

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Stephen Harrington Thesis

PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE BEYOND JOURNALISM: INFOTAINMENT, SATIRE AND AUSTRALIAN TELEVISION STEPHEN HARRINGTON BCI(Media&Comm), BCI(Hons)(MediaSt) Submitted April, 2009 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology, Australia 1 2 STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made. _____________________________________________ Stephen Matthew Harrington Date: 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changing relationships between television, politics, audiences and the public sphere. Premised on the notion that mediated politics is now understood “in new ways by new voices” (Jones, 2005: 4), and appropriating what McNair (2003) calls a “chaos theory” of journalism sociology, this thesis explores how two different contemporary Australian political television programs (Sunrise and The Chaser’s War on Everything) are viewed, understood, and used by audiences. In analysing these programs from textual, industry and audience perspectives, this thesis argues that journalism has been largely thought about in overly simplistic binary terms which have failed to reflect the reality of audiences’ news consumption patterns. The findings of this thesis suggest that both ‘soft’ infotainment (Sunrise) and ‘frivolous’ satire (The Chaser’s War on Everything) are used by audiences in intricate ways as sources of political information, and thus these TV programs (and those like them) should be seen as legitimate and valuable forms of public knowledge production. -

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For GTV/SD Sun Apr 24, 2011 06:00 A VERY SPECIAL FATHER WS G A Very Special Father A closer look at the various ministries of the Sisters and how the Heavenly Father has lovingly cared for them. A fountain was built to remind them and their visitors of just how special He is. 06:30 DORA THE EXPLORER G Catch the Babies It's a bright, sunny morning, and Dora wants to say hello to her baby brother and sister. 07:00 WEEKEND TODAY Captioned WS NA Join Cameron Williams and Leila McKinnon as they bring you the latest in news, current affairs, sports, politics, entertainment, fashion, health and lifestyle. 10:00 WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS Captioned WS G Join Ken Sutcliffe and guest hosts Grant Hackett, Giaan Rooney and Michael Slater for all the overnight news and scores, sports features, special guests and light-hearted sporting moments. 11:00 THE SUNDAY FOOTY SHOW Live WS G Hosted by James Brayshaw, The Sunday Footy Show reviews all the AFL action and big stories with regular panellists Billy Brownless, Shane Crawford, Nathan Thompson and Brian Taylor. 13:00 GILLIGAN'S ISLAND Repeat G Smile, You're on Mars Camera NASA has sent a camera into space in hopes of landing on Mars. But instead, the camera has landed on the island. Elsewhere, Gilligan has been put in charge of collecting feathers by Mrs. Howell to make Thurston a mattress for his birthday. 13:30 THE FRESH PRINCE OF BEL AIR Repeat G All Guts No Glory Registration day sees Will signing up for a class that may truly challenge him - a philosophy course he takes to meet a girl. -

ZZZ-Appendices-Mathesis-Tmcl

Appendices-P1 Appendix 1: MEAA Code of Ethics for Australian Journalists A: Current version of code (1997-) (available from Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (AJA subsection) website at http://www.alliance.org.au/hot/ethicscode.htm) Respect for truth and the public’s right to information are fundamental principles of journalism. Journalists describe society to itself. They convey information, ideas and opinions, a privileged role. They search, disclose, record, question, entertain, suggest and remember. They inform citizens and animate democracy. They give a practical form to freedom of expression. Many journalists work in private enterprise, but all have these public responsibilities. They scrutinise power, but also exercise it, and should be accountable. Accountability engenders trust. Without trust, journalists do not fulfil their public responsibilities. MEAA members engaged in journalism commit themselves to • Honesty • Fairness • Independence • Respect for the rights of others 1 Report and interpret honestly, striving for accuracy, fairness and disclosure of all essential facts. Do not suppress relevant available facts, or give distorting emphasis. Do your utmost to give a fair opportunity for reply. 2 Do not place unnecessary emphasis on personal characteristics, including race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, age, sexual orientation, family relationships, religious belief, or physical or intellectual disability. 3 Aim to attribute information to its source. Where a source seeks anonymity, do not agree without first considering the source’s motives and any alternative attributable source. Where confidences are accepted, respect them in all circumstances. 4 Do not allow personal interest, or any belief, commitment, payment, gift or benefit, to undermine your accuracy, fairness or independence. -

Melbourne Program Guide

Page 1 of 24 Melbourne Program Guide Sun Aug 26, 2012 06:00 TEAM UMIZOOMI Repeat G Team Umizoomi is an animated interactive math series for pre-schoolers. 06:30 DORA THE EXPLORER Repeat G Save Diego Dora's cousin Diego protects and defends all the animals in the rainforest. But in order to save a Baby Condor, Diego winds up trapped himself. 07:00 WEEKEND TODAY Captioned Live WS NA Join Cameron Williams and Leila McKinnon as they bring you the latest in news, current affairs, sports, politics, entertainment, fashion, health and lifestyle. 10:00 WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS Captioned Live WS G Best Of London Join Ken Sutcliffe and guest hosts Grant Hackett, Giaan Rooney and Michael Slater as we look back at some of the best of London as well as all the overnight news and scores, sports features, special guests and light-hearted sporting moments. 11:00 THE SUNDAY FOOTY SHOW Live WS G Hosted by Simon O’Donnell, The Sunday Footy Show reviews all the AFL action and big stories with regular panellists Billy Brownless, Shane Crawford, Matthew Lloyd, Damian Barrett and Nathan Brown. Each week, Christie Malthouse joins the boys to discuss the latest news and sports scores from around Australia and abroad 13:00 TAC CUP: FUTURE STARS Live WS PG TAC Cup: Future Stars showcases the country's brightest football prospects from the TAC Cup Competition. Also hear from AFL stars who re-trace their days of an unknown to football stardom. Hosted by Craig Hutchison. 14:00 GILLIGAN'S ISLAND Repeat G The Sweepstakes Gilligan has a sweepstakes ticket in his possession which contains the winning numbers. -

2020 NRMA Kennedy Awards' Finalists

2020 NRMA Kennedy Awards’ Finalists Media release embargoed 7pm, Wednesday 22 July 2020 Categories and finalists 1 Les Kennedy Award for Outstanding Crime Reporting - Simon Bouda (A Current Affair); Australian Story: An Innocent Abroad (ABC); Michael Usher and team: Framed, the story of Scott Austic (7 News) 2 Paul Lockyer Award for Outstanding Regional Broadcast Reporting (sponsor AGL) – Prime 7 Local News - Coast Team; Jane Goldsmith (NBN News); ABC Background Briefing/Landline 3 Chris Watson Award for Outstanding Regional Newspaper Reporting (sponsor AGL) – Carla Hildebrandt (Mandurah Mail); Madeline Link (Northern Daily Leader); The Tumut and Adelong Times, Tumbarumba Times 4 Rod Allen Award for Racing Writer of the Year (sponsor Australian Turf Club) – Damien Ractliffe, Chip Le Grand (The Age); Ray Thomas (Daily Telegraph); Chris Roots (Sydney Morning Herald 5 Sean Flannery Award for Outstanding Radio Journalism (sponsor Hillbrick Bicycles) – Gavin Coote (ABC Audio Current Affairs); Steve Cannane and Kyle Taylor (ABC Background Briefing); Elini Psaltis (World Today ABC) 6 Outstanding Podcast (sponsor broadcast voice coach Sally Prosser) – Mark Whittaker: Blood Territory; Kimberley Pratt and Stephanie Coombes: First Person series (10 News First); The Eleventh (ABC Radio Programs) 7 Outstanding News Photo (sponsor Salty Dingo) – Sam Ruttyn (Sunday Telegraph); Nick Moir (Sydney Morning Herald); Dallas Kilponen (freelance pic for the Sydney Morning Herald) 8 Outstanding Portrait (sponsor Salty Dingo) – Richard Dobson (Sunday Telegraph); -

Commercial Radio Australia

MEDIA RELEASE 22 September 2016 Chris Taylor and Andrew Hansen to host the 28th annual Australian Commercial Radio Awards Chris Taylor and Andrew Hansen, best known as members of the comedy group The Chaser, will host the 28th annual Australian Commercial Radio Awards (ACRAs) in Melbourne. Chris and Andrew were part of the full Chaser team that made their radio debut on Triple M (2003) with The Friday Chaser. They have worked on radio throughout their careers and in 2015 toured their live show, a parody of celebrity Q&As entitled In Conversation with Lionel Corn. Chris is currently a regular co-host of the Merrick & Australia national drive show on Triple M and presenter of the We Was Robbed, alongside HG Nelson on Kinderling Kids Radio on DAB+ digital radio. Writers, producers and stars of the TV shows Media Circus (2014-15), The Hamster Wheel (2011- 2013), Yes We Canberra! (2010), The Chaser’s War On Everything (2006-9), The Chaser Decides (2004, 2007), CNNNN (2002-3) and The Election Chaser (2001). Their shows won two AFI awards and two Logies. The ACRAs recognise excellence in radio broadcasting across news, talk, sport, music and entertainment. Commercial Radio Australia chief executive officer, Joan Warner said: “The ACRAs are the highlight of the year for the radio industry and we look forward to Chris and Andrew hosting the awards this year in Melbourne.” Radio announcers joining Chris and Andrew on stage to present awards will include: Hamish & Andy – Hit Network (Hamish Blake & Andy Lee) Jonesy & Amanda – WSFM (Brendan Jones & Amanda Keller) Kate, Tim & Marty – Nova Network (Kate Ritchie, Tim Blackwell & Marty Sheargold) Neil Mitchell – 3AW Rove & Sam – 2Day FM (Rove McManus & Sam Frost) Merrick Watts – Triple M, Southern Cross Austereo Jo & Lehmo – Gold 104.3 (Jo Stanley & Anthony Lehmann) Mike E & Emma – The Edge (Michael Etheridge & Emma Chow) The list of ACRA finalists is available here. -

SENATE Official Committee Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA SENATE Official Committee Hansard INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES COMMITTEE Reference: Self-regulation in the information and communication industries WEDNESDAY, 22 APRIL 1998 SYDNEY BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CANBERRA 1997 INTERNET The Proof and Official Hansard transcripts of Senate committee hearings, some House of Representatives committee hearings and some joint committee hearings are available on the Internet. Some House of Representatives committees and some joint committees make available only Official Hansard transcripts. The Internet address is: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard SENATE Wednesday, 22 April 1998 SELECT COMMITTEE ON INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES Members: Senator Ferris (Chair), Senator Quirke (Deputy Chair), Senators Calvert, Harradine, McGauran, Tierney, Reynolds and Stott Despoja Senators attending the hearing: Senator Ferris (Chair), Senator Quirke (Deputy Chair), Senators Calvert and Harradine Matter referred by the Senate for inquiry into and report on: Evaluate the appropriateness, effectiveness and privacy implications of the existing self-regulatory framework in relation to the information and communications industries and, in particular, the adequacy of the complaints regime. WITNESSES BLOCK, Ms Jessica, Corporate Counsel, Nine Network, 24 Artarmon Road, Willoughby, New South Wales 2068 ................................. 332 BRANIGAN, Mr Anthony Michael, General Manager, Federation of Australian Commercial Television Stations, 44 Avenue Road, Mosman, New South Wales 2088 ....................................................... -

SSH – October 2007

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FIFTY-FIVE OCTOBER’07 CIRCULATION 22,000 ALEXANDRIA BEACONSFIELD CHIPPENDALE DARLINGTON ERSKINEVILLE KINGS CROSS NEWTOWN PADDINGTON REDFERN SURRY HILLS WATERLOO WOOLLOOMOOLOO ZETLAND WRAPPED THE BEST WITH LOVE BURGERS Local charity celebrates 15 years of good service IN TOWN PAGE 6 The Review PAGE 9 Emily, Charles Firth and Nick at Darlington Newsagency Photo: Ali Blogg Manic Times surprises Most people would recognise Charles Firth as one of the original reporters on Over-reaction? CNNNN and the Election Chaser. And while he remains the Chaser’s War Riot police on Sydney streets Photo: Lisa Hogben on Everything US correspondent, he has returned to Australia as Editor in Chief of Sydney’s newest rag, the Manic Times. If you expect the paper to be more satirical stories from the wayward Firth and friends, then you will be Nicholas McCallum McKinley, Urban Guerrillas’ Ken and the Philippines. Stewart and Iraq Veterans Against Whilst one man was arrested pleasantly surprised. It would seem that the only the War and former US Marine Matt for squirting sauce upon the conclusions to draw from the Howard speaking out against the war pro-American banner, many in Nicholas McCallum the way of gonzo [journalism] in APEC Summit are that when and APEC. the crowd were perplexed as to why Australia,” Firth said, “We’d like to Sydney protests it does so The protest was proceeding the NSW police would permit two After spending the last two years have one 5000 word gonzo piece peacefully and that NSW police peacefully with many questioning demonstrations with opposing views in the States writing his first book, every issue.” are still getting it wrong when the need for such a heavy police to come into such close quarters. -

The Chaser's Media Circus

ABC TV Media Release ABC ANNOUNCES PLAN TO REPLACE THE CHASER’S MEDIA CIRCUS WITH CAT VIDEOS ABC TV management has confirmed it hopes to replace the second series of The Chaser’s Media Circus with cat videos. “As soon as we can find enough left wing cats who instinctively hate Australia, they’ll be replaced,” said an ABC representative. Media Circus – the game show about the news game hosted by Craig Reucassel with Fake Fact Checker Chas Licciardello – returns to ABC on Thursday 10 September at 8pm. It is produced by the creative team behind The Chaser and The Checkout, including Ben Jenkins, Zoë Norton Lodge, Scott Abbot, Andrew Hansen and Julian Morrow. ABC management confirmed that for the second series the show has been moved out of the news division to allow it to be more biased and have less rigorous vetting of the studio audience. Filmed in front of a live audience each week shortly before broadcast, The Chaser’s Media Circus brings together journalists and comedians to dissect the week’s news through a time- honoured technique of media criticism: the trivia quiz. Last year’s guests included George Negus, Senator Nick Xenophon, Lenore Taylor, Chris Kenny, Ellen Fanning, Tracey Spicer, Hugh Riminton, Peter Berner, Dave Hughes and Tom Gleeson, a number of whom have not yet refused to return for Series Two. The new series will also feature Media Circus first timers including Peter Greste and John Safran. Prime Minister Abbott has confirmed he will allow government front benchers to appear on the show. But the producers are lobbying him to have this decision reversed. -

Budget Estimates 2009-2010

Senate Standing Committee on Environment, Communications and the Arts Answers to Senate Estimates Questions on Notice Budget Estimates Hearings May 2009 Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy Portfolio Australian Broadcasting Corporation Question No: 134 Program: 1.2 Hansard Ref: ECA 40 Topic: Rating of sport on ABC2 Senator Lundy asked: Can you provide the committee with any information about the respective ratings of the football and the WNBL, and how it performed as content? Answer: The average rating across the whole season for the WNBL broadcast on ABC2 on Friday nights was 14,000 viewers. This compares with an average audience on Friday nights on ABC2 of 40,000 viewers since the WNBL season concluded. For the Saturday afternoon broadcasts (which were usually repeats of the Friday night matches) the average audience across the season was 59,000 viewers with a peak of 84,000 viewers for the Grand Final. The W-League (women’s football) had an average audience across the season of 73,000 viewers with a peak of 104,000 for the Grand Final. ABC2 has not broadcast any football this year. The WNBL (screening on ABC2 Friday evenings) this year did not perform well. The highest average audience (on Friday 13 February) was 21,000 viewers. Page 1 of 1 Senate Standing Committee on Environment, Communications and the Arts Answers to Senate Estimates Questions on Notice Budget Estimates Hearings May 2009 Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy Portfolio Australian Broadcasting Corporation Question No: 135 Program: 1.2 Hansard Ref: ECA 40 Topic: Penetration of ABC2 Senator Lundy asked: Could you provide details of the penetration of ABC2 to date? Answer: According to the Government’s Digital Switchover Taskforce’s first digital tracker report (First Quarter 2009), an estimated 47 per cent of Australian homes have converted to digital terrestrial television. -

Andrew Hansen

Andrew Hansen Comedian, musician, MC and The Chaser star Andrew Hansen is a comedian, pianist, guitarist, composer and vocalist as well as a writer and performer who is best known as a member of the Australian satirical team on ABC TV’s The Chaser. Andrew is very versatile on the corporate stage too. He can MC an event, give a custom-written comedy presentation or even compose and perform a song if inspired to do so. Andrew’s radio work includes shows on Triple M as well as composing and starring in the musical comedy series and ARIA Award winning album The Blow Parade (triple j, 2010). The Chaser’s TV shows include Media Circus (2014-15), The Hamster Wheel (2011-2013), Yes We Canberra! (2010), The Chaser’s War On Everything (2006-9), The Chaser Decides (2004, 2007) and CNNNN (2002-3). On the Seven network, Andrew produced The Unbelievable Truth (2012). He has also appeared as a guest on most Australian TV shows that have guests. In print he wrote for the humorous fortnightly newspaper The Chaser (1999-2005), eleven Chaser Annuals (Text Publishing, 2000-10), and for the recently launched Chaser Quarterly (2015). On stage Andrew composed and starred in the musical Dead Caesar (Sydney Theatre Company), did two national tours with The Chaser, and two live collaborations with Chris Taylor (One Man Show, 2014 and In Conversation with Lionel Corn, 2015). The Chaser team also runs a cool theatre in Sydney called Giant Dwarf. Andrew composed all The Chaser’s songs as well as the theme music for Media Circus and The Chaser’s War On Everything.