Narragansett Bay Watershed Counts 2016 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington County Flood Insurance Study Vol 4

VOLUME 4 OF 4 WASHINGTON COUNTY, RHODE ISLAND (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER CHARLESTOWN, TOWN OF 445395 EXETER, TOWN OF 440032 HOPKINTON, TOWN OF 440028 NARRAGANSETT INDIAN TRIBE 445414 NARRAGANSETT, TOWN OF 445402 NEW SHOREHAM, TOWN OF 440036 NORTH KINGSTOWN, TOWN OF 445404 RICHMOND, TOWN OF 440031 SOUTH KINGSTOWN, TOWN OF 445407 WESTERLY, TOWN OF 445410 REVISED: APRIL 3, 2020 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 44009CV004C Version Number 2.3.3.2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 3 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 15 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 15 2.2 Floodways 18 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 19 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 19 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 19 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 19 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 21 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 22 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 23 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 24 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 24 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED 24 4.1 Basin Description 24 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 26 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 36 4.4 Levees 36 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 38 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 38 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 44 5.3 Coastal Analyses 50 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 52 5.3.2 Waves 52 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 53 5.3.4 -

4. Hydraulic Data on Saugatucket River

RHODn E TISLAND DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT 235 Promenade Street, Providence, RI 02908-5767 TDD 40 1-83 1-5508 February 24,1999 Stephen A. Alfred, Town Manager ;7 Town of South Kingstown i 180 High Street " -. ' Wakefield, Rhode Island 02880 ~~ -- -—.___ J Dear Mr. Alfred: The Department of Environmental Management recently received a draft report summarizing water quality investigations in the Saugatucket River conducted by Dr. Raymond Wright of the University of Rhode Island's Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. A copy of Dr. Wright's report is attached for your information. The document is presently in draft form and is being reviewed by DEM's Office of Water Resources staff. Dr. Wright's work was conducted to assess impairments of water quality along the river and its tributaries and to allow estimates of impacts on Point Judith Pond. Three water bodies in the Saugatucket watershed are included on the State's current list of impaired waters (also known as the 303(d) list): Mitchell Brook, Saugatucket River, and Saugatucket Pond. These water bodies, as you know, respectively flow through, form the eastern border, and are immediately downstream of the former landfill site. It is our concern that each of these three water body impairments is attributable to influences from the landfill. Chapter 10 of Dr. Wright's study associates the site with a significant increase in ammonia concentrations in the main stem of the Saugatucket River. The federal Clean Water Act requires that the cause and source of water quality impairment and actions to restore water quality be identified, in an analysis known as a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), for all water bodies listed on the state's 303(d) list. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

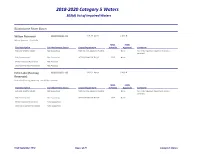

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED -

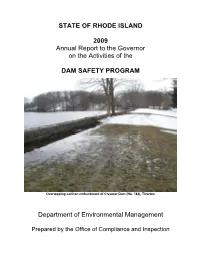

Dam Safety Program

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND 2009 Annual Report to the Governor on the Activities of the DAM SAFETY PROGRAM Overtopping earthen embankment of Creamer Dam (No. 742), Tiverton Department of Environmental Management Prepared by the Office of Compliance and Inspection TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY OF RHODE ISLAND’S DAM SAFETY PROGRAM....................................................................3 STATUTES................................................................................................................................................3 GOVERNOR’S TASK FORCE ON DAM SAFETY AND MAINTENANCE .................................................3 DAM SAFETY REGULATIONS .................................................................................................................4 DAM CLASSIFICATIONS..........................................................................................................................5 INSPECTION PROGRAM ............................................................................................................................7 ACTIVITIES IN 2009.....................................................................................................................................8 UNSAFE DAMS.........................................................................................................................................8 INSPECTIONS ........................................................................................................................................10 High Hazard Dam Inspections .............................................................................................................10 -

' <• ' >'•'(' FINAL RULE Adopted by the Rhode Island Rivers Council July

SL, ciiuiiJ KutoiUa Center Si i L: O^' <• ' >'•'(' FINAL RULE Adopted by the Rhode Island Rivers Council July 13,2005 SDMS DocID 273446 State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Rhode Island Rivers Council PO Box 1565 North Kingstown, RI 02852 RULES AND REGULATIONS OF THE RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL FOR WATERSHED COUNCIL GRANTS AND NOTIFICATION OF PROPOSED ACTIONS TO WATERSHED COUNCILS June 2005 Rule 1: Grant Funding for Watershed Councils/Associations R.I.G.L. Section 46-28-7(7) authorizes the Council to provide grants to local watershed councils/associations. 1.1 Eligibility Only those Watershed Councils/Associations formally designated by the Council are eligible for grants from the Council. 1.2 Allocation of Available Funds Upon determining the level of funding available, the Council may: 1.2.1 Set a maximum per project funding limit. 1.2.2 Establis ha maximum number of submissions per applicant for funding proposals. 1.2.3 Establish funding categorie ans d funding allocation for each category. 1.3 Solicitation of Grant Applicants In the event that funds are available, the Council shall solicit and accept grant applications. 1.4 Grant Application Form The Council shall develop and adopt a grant application form that shall qualify an applicant for consideration of receiving a grant. Application forms shall be distributed to organizations upon request. 1.5 Grant Application Acceptability Applications found to be complete will be referred to the Council for evaluation. Applications found to be incomplete will be returned to the applicant with a statement as to the deficiencies noted and a notice that the applicant can correct these and resubmit the application. -

Rhode Island's Shellfish Heritage

RHODE ISLAND’S SHELLFISH HERITAGE RHODE ISLAND’S SHELLFISH HERITAGE An Ecological History The shellfish in Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island’s salt ponds have pro- vided humans with sustenance for over 2,000 years. Over time, shellfi sh have gained cultural significance, with their harvest becoming a family tradition and their shells ofered as tokens of appreciation and represent- ed as works of art. This book delves into the history of Rhode Island’s iconic oysters, qua- hogs, and all the well-known and lesser-known species in between. It of ers the perspectives of those who catch, grow, and sell shellfi sh, as well as of those who produce wampum, sculpture, and books with shell- fi sh"—"particularly quahogs"—"as their medium or inspiration. Rhode Island’s Shellfish Heritage: An Ecological History, written by Sarah Schumann (herself a razor clam harvester), grew out of the 2014 R.I. Shell- fi sh Management Plan, which was the first such plan created for the state under the auspices of the R.I. Department of Environmental Management and the R.I. Coastal Resources Management Council. Special thanks go to members of the Shellfi sh Management Plan team who contributed to the development of this book: David Beutel of the Coastal Resources Manage- Wampum necklace by Allen Hazard ment Council, Dale Leavitt of Roger Williams University, and Jef Mercer PHOTO BY ACACIA JOHNSON of the Department of Environmental Management. Production of this book was sponsored by the Coastal Resources Center and Rhode Island Sea Grant at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, and by the Coastal Institute at the University SCHUMANN of Rhode Island, with support from the Rhode Island Council for the Hu- manities, the Rhode Island Foundation, The Prospect Hill Foundation, BY SARAH SCHUMANN . -

RIRC Booklet Combined 2 27 2019

THE RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL www.ririvers.org One Capitol Hill Providence, Rhode Island 02908 [email protected] RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Veronica Berounsky, Chair Alicia Eichinger, Vice Chair Robert Billington Rachel Calabro Walter Galloway Charles Horbert Elise Torello INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS Paul Gonsalves for Michael DiBiase, Department of Administration Eugenia Marks for Kathleen Crawley, Water Resources Board Ernie Panciera for Janet Coit, Department of Environmental Management Peder Schaefer for Mayor James Diossa, League of Cities and Towns Mike Walker for Stefan Pryor, Commerce Corporation Jeff Willis for Grover Fugate, Coastal Resource Management Council ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Photographs in this publication provided by: Rhode Island Rivers Council Elise Torello, cover photograph, Upper Wood River Charles Biddle, "Children Planting, Middlebridge", pg. 1 Booklet compilation and design services provided by Liz Garofalo THANK YOU This booklet was made possible by a RI legislative grant sponsored by Representatives: Carol Hagan McEntee, (D-District 33, South Kingstown/Narragansett) Robert E. Craven, Sr., (D-District 32, North Kingstown) 2 RHODERHODE ISLANDISLAND WATERSHEDS WATERSHEDS MAP MAP 3 RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL ABOUT US The Rhode Island Rivers Council (RIRC) is charged with coordinating state policies to protect rivers and watersheds. Our unique contribution is to strengthen local watershed councils as partners in rivers and watershed protection. Created by statute (RIGL 46-28) in 1991 as an associated function of the Rhode Island Water Resources Board, the RIRC mission is to preserve and improve the quality of Rhode Island's rivers and their watersheds and to work with public entities to develop plans to safely increase river use. Under the Rhode Island Rivers Council statute, rivers are defined as "a flowing body of water or estuary, including streams, creeks, brooks, ponds, coastal ponds, small lakes, and reservoirs." WHAT WE DO The RIRC plays a key role in the state's comprehensive environmental efforts. -

Strategic Plan for the Restoration of Anadromous Fishes to Rhode

STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE RESTORATION OF ANADROMOUS FISHES TO RHODE ISLAND COASTAL STREAMS American Shad, Alosa sapidissima D. Raver, USFWS Prepared By: Dennis E. Erkan, Principal Marine Biologist Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Division of Fish and Wildlife Completion Report In Fulfillment of Federal Aid In Sportfish Restoration Project F-55-R December 2002 Special thanks to Luther Blount for initiating this project. Rhode Island Anadromous Restoration Plan CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................Page 6 Methods..............................................................................................................................Page 7 I. Plan Objective...............................................................................................................Page 11 II. Expected Results or Benefits ......................................................................................Page 11 III. Strategic Plan.............................................................................................................Page 12 IV. References.................................................................................................................Page 15 V. Additional Sources of Information...............................................................................Page 16 APPENDICES Appendix A. Recommended Watershed Enhancements.....................................................Page 20 Appendix B. Description -

W R Wash Rhod Hingt De Isl Ton C Land Coun D Nty

WASHINGTON COUNTY, RHODE ISLAND (ALL JURISDICTIONS) VOLUME 1 OF 2 COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER CHARLESTOWN, TOWN OF 445395 EXETER, TOWN OF 440032 HOPKINTON, TOWN OF 440028 NARRAGANSETT INDIAN TRIBE 445414 NARRAGANSETT, TOWN OF 445402 NEW SHOREHAM, TOWN OF 440036 NORTH KINGSTOWN, TOWN OF 445404 RICHMOND, TOWN OF 440031 SOUTH KINGSTOWN, TOWN OF 445407 Washingtton County WESTERLY, TOWN OF 445410 Revised: October 16, 2013 Federal Emergency Management Ageency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 44009CV001B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: October 19, 2010 Revised Countywide FIS Date: October 16, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS – Volume 1 – October 16, 2013 Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of Study 1 1.2 Authority and Acknowledgments 1 1.3 Coordination 4 2.0 -

Habits of Juvenile Fishes in Two Rhode Island Estuaries

Gulf and Caribbean Research Volume 2 Issue 2 January 1966 Habits of Juvenile Fishes in Two Rhode Island Estuaries Mohammed Saeed Mulkana Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/gcr Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Mulkana, M. S. 1966. Habits of Juvenile Fishes in Two Rhode Island Estuaries. Gulf Research Reports 2 (2): 97-167. Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/gcr/vol2/iss2/2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18785/grr.0202.02 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf and Caribbean Research by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Growth And Feeding Habits of Juvenile Fishes In Two Rhode Island Estuaries bY MOHAMMED SAEED MULKANA 97 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .................................................................................................. 100 LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................... 101 LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................... 102 I . INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 103 I1 . REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ............................................ 106 I11 . METHODS AND MATERIALS ................................................ 107 IV. THE ENVIRONMENT ......................................................... 109 A . Topographic and Edaphic