Comprehensive Plan: Baseline Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narrow River Watershed Plan (Draft)

DRAFT Narrow River Watershed Plan Prepared by: Office of Water Resources Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management 235 Promenade Street Providence, RI 02908 Draft: December 24, 2019, clean for local review DRAFT Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 8 A) Purpose of Plan................................................................................................................. 8 B) Water Quality and Aquatic Habitat Goals for the Watershed ........................................ 12 1) Open Shellfishing Areas ............................................................................................. 12 2) Protect Drinking Water Supplies ................................................................................ 12 3) Protect and Restore Fish and Wildlife Habitat ........................................................... 12 4) Protect and Restore Wetlands and Their Buffers ....................................................... 13 5) Protect and Restore Recreational Opportunities ......................................................... 14 C) Approach for Developing the Plan/ How this Plan was Developed .............................. 15 II. Watershed Description ......................................................................................................... -

Washington County Flood Insurance Study Vol 4

VOLUME 4 OF 4 WASHINGTON COUNTY, RHODE ISLAND (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER CHARLESTOWN, TOWN OF 445395 EXETER, TOWN OF 440032 HOPKINTON, TOWN OF 440028 NARRAGANSETT INDIAN TRIBE 445414 NARRAGANSETT, TOWN OF 445402 NEW SHOREHAM, TOWN OF 440036 NORTH KINGSTOWN, TOWN OF 445404 RICHMOND, TOWN OF 440031 SOUTH KINGSTOWN, TOWN OF 445407 WESTERLY, TOWN OF 445410 REVISED: APRIL 3, 2020 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 44009CV004C Version Number 2.3.3.2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 3 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 15 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 15 2.2 Floodways 18 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 19 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 19 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 19 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 19 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 21 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 22 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 23 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 24 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 24 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED 24 4.1 Basin Description 24 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 26 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 36 4.4 Levees 36 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 38 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 38 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 44 5.3 Coastal Analyses 50 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 52 5.3.2 Waves 52 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 53 5.3.4 -

Red Skies and Blue Collars

A 1976 view of Sparrows Point’s coke ovens, which were closed in 1992 for air-quality reasons. The ovens converted coal BY BETTY JOYCE NASH into coke, the fuel used to fire steelmaking furnaces. evin Nozeika lost his job of 16 years at Sparrows Motors, Western Electric, Signode Strapping, Thompson Point last summer when the steel company’s fourth Steel, Continental Can, and Crown Cork and Seal employed Kowner in a decade, RG Steel, went bankrupt. His thousands. father retired from another now-departed Baltimore steel- Once the site was nothing but desolate marshland jutting maker. Nozeika worked there, too, with 2,000 others, until into the Chesapeake, but as historians often say, geography it closed. “I’m an old hand at shutting down steel mills in is destiny. the Baltimore area,” Nozeika jokes. He started working in steel just before his 20th birthday. He’s now 44. Forging an Industry Sparrows Point’s flaring furnaces reddened the skies The Pennsylvania Steel Co. in 1887 sent its engineer, above Baltimore Harbor for more than a century. Workers Frederick Wood, to scout the East Coast for a site conve- made steel for rails, bridges, ships, cars, skyscraper skele- niently located to receive iron ore shipments from the firm’s tons, nails, wire, and tin cans. captive Cuban mines; there, they’d transform the iron It was a remarkable run. “If you look at Sparrows Point’s into steel for rails. Sparrows Point lay 100 miles closer to history, there were times when the different generations of Cuba than Philadelphia and 65 miles closer to western blast furnaces, or the rolling mills, or the coke works were Pennsylvania’s bituminous coal fields. -

Kayak Guide V4.Indd

Kayak Rentals A KAYAKER’S GUIDE TO THE COASTAL SALT PONDS OF SOUTH COUNTY, RHODE ISLAND Arthur R. Ganz Mark F. Bullinger KAYAKER’S GUIDE KAYAKER’S Salt Ponds Coalition Salt Ponds Coalition www.saltpondscoalition.org Stewards for the Coastal Environment South County Salt Ponds Westerly through Narragansett Acknowledgements Th e authors wish to thank the R.I. Rivers Council for its support of this project. Th anks as well to Bambi Poppick and Sharon Frost for editorial assistance. © 2007 - Salt Ponds Coalition, Box 875, Charlestown, RI 02813 - www.saltpondscoalition.org Introduction Th e salt ponds are a string of coast- Today, most areas of the salt ponds ways of natural beauty, ideal for relaxed al lagoon estuaries formed aft er the re- are protected by the dunes of the barri- paddling enjoyment. cession of the glaciers 12,000 years ago. er beaches, making them gentle water- Piled sediment called glacial till formed the rocky ridge called the moraine Safety (running along what is today Route Like every outdoor activity, proper preparation and safety are the key components of an One). Irregularities along the coast- enjoyable outing. Please consider the following percautions. line were formed by the deposit of the • Always wear a proper life saving de- pull a kayaker out to sea. Be particu- glaciers, which form peninsula-shaped vice and visible colors larly cautious venturing into sections outcroppings, which are now known • Check the weather forecast. Th e ponds that are lined by stone walls - pulling as Point Judith, Matunuck, Green Hill, can get rough over and getting out becomes probli- • Dress for the weather matic in these areas. -

Ph River, Brook and Tributary Sites the Normal Ph Range For

2016 Parameter Data: pH River, Brook and Tributary Sites The standard measurement of acidity is pH. A pH of less than 7 is acidic; above pH 7 is alkaline, also known by the term “basic.” The pH measurement is a logarithmic measurement, which means that each unit decrease in pH equals a ten-fold increase in acidity. In other words, pH 5 water is ten times more acidic than pH 6 water. Aquatic organisms need the pH of their water body to be within a certain range for optimal growth and survival. Although each organism has an ideal pH, most aquatic organisms prefer pH of 6.5 – 8.0. Watershed LOCATION MAY JUNE JULY AUG. SEPT. OCT. Miniumum Code RIVERS - - - - - - Standard pH units - - - - - - A Annaquatucket River - 7.2 6.9 6.6 6.8 6.9 6.7 6.6 Belleville @ Railroad Crossing WD Ashaway River @ Rte 216 6.8 6.6 6.5 6.8 7.1 6.8 6.5 WD Beaver River @ Rte 138 6.3 6.5 6.6 6.8 6.3 6.1 6.1 NA Buckeye Brook #1 @ Novelty Rd 7.0 7.2 6.5 7.2 6.9 7.0 6.5 NA Buckeye Brk #2 @ Lockwood Brk - 6.7 6.9 6.8 - - 6.7 NA Buckeye Brk #3 @ Warner Brook 6.7 6.5 6.4 6.5 6.5 - 6.4 NA Buckeye Brook #4 @ Mill Cove 6.9 7.0 6.4 7.0 7.0 - 6.4 WD Falls River D - Step Stone Falls 6.4 6.4 6.6 6.5 6.6 6.3 6.3 WD Falls River C - Austin Farm Rd. -

4. Hydraulic Data on Saugatucket River

RHODn E TISLAND DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT 235 Promenade Street, Providence, RI 02908-5767 TDD 40 1-83 1-5508 February 24,1999 Stephen A. Alfred, Town Manager ;7 Town of South Kingstown i 180 High Street " -. ' Wakefield, Rhode Island 02880 ~~ -- -—.___ J Dear Mr. Alfred: The Department of Environmental Management recently received a draft report summarizing water quality investigations in the Saugatucket River conducted by Dr. Raymond Wright of the University of Rhode Island's Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. A copy of Dr. Wright's report is attached for your information. The document is presently in draft form and is being reviewed by DEM's Office of Water Resources staff. Dr. Wright's work was conducted to assess impairments of water quality along the river and its tributaries and to allow estimates of impacts on Point Judith Pond. Three water bodies in the Saugatucket watershed are included on the State's current list of impaired waters (also known as the 303(d) list): Mitchell Brook, Saugatucket River, and Saugatucket Pond. These water bodies, as you know, respectively flow through, form the eastern border, and are immediately downstream of the former landfill site. It is our concern that each of these three water body impairments is attributable to influences from the landfill. Chapter 10 of Dr. Wright's study associates the site with a significant increase in ammonia concentrations in the main stem of the Saugatucket River. The federal Clean Water Act requires that the cause and source of water quality impairment and actions to restore water quality be identified, in an analysis known as a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), for all water bodies listed on the state's 303(d) list. -

RI DEM/Parks and Recreation- Park and Management Area Rules And

State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Department of Environmental Management Division of Law Enforcement, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Division of Forest Environment, and Division of Parks and Recreation Park and Management Area Rules and Regulations November, 2010 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted pursuant to Chapters 42.17.1, 42.17.6, 20-18, 20-15, 32-2 and 32-3, and RIGL §§20-1-2, 20-1-4, and 20-1-8, and 42-35 “Administrative Procedures Act” of the General Laws of Rhode Island, 1956 as amended. State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Department of Environmental Management Division of Law Enforcement Division of Fish and Wildlife Division of Forest Environment Division of Parks and Recreation TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AUTHORITY......................................................................................................................................... 3 ADMINISTRATIVE FINDINGS .......................................................................................................... 3 APPLICATION...................................................................................................................................... 3 SEVERABILITY ................................................................................................................................... 3 SUPERSEDED RULES AND REGULATIONS.................................................................................. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder

Fishery Management Report No. 43 of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Working towards healthy, self-sustaining populations for all Atlantic coast fish species or successful restoration well in progress by the year 2015. Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder November 2005 Fishery Management Report No. 43 of the ATLANTIC STATES MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder Approved: February 10, 2005 Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder Prepared by Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Winter Flounder Plan Development Team Plan Development Team Members: Lydia Munger, Chair (ASMFC), Anne Mooney (NYSDEC), Sally Sherman (ME DMR), and Deb Pacileo (CT DEP). This Management Plan was prepared under the guidance of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Winter Flounder Management Board, Chaired by David Borden of Rhode Island followed by Pat Augustine of New York. Technical and advisory assistance was provided by the Winter Flounder Technical Committee, the Winter Flounder Stock Assessment Subcommittee, and the Winter Flounder Advisory Panel. This is a report of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA04NMF4740186. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 Introduction The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) authorized development of a Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) in October 1988. Member states declaring an interest in this species were the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware. -

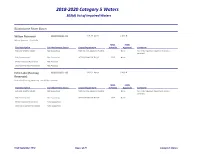

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

By Herbert E. Johnston and David C. Dickerman Water-Resources

HYDROLOGY, WATER QUALITY, AND GROUND-WATER-DEVELOPMENT ALTERNATIVES IN THE CHIPUXET GROUND-WATER RESERVOIR, RHODE ISLAND By Herbert E. Johnston and David C. Dickerman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 84-4254 Prepared in cooperation with the Rhode Island Water Resources Board Providence, Rhode Island 1985 HYDROLOGY, WATER QUALITY, AND GROUND-WATER-DEVELOPMENT ALTERNATIVES IN THE CHIPUXET GROUND-WATER RESERVOIR, RHODE ISLAND By Herbert E. Johnston and David C. Dickerman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 84-4254 Prepared in cooperation with the Rhode Island Water Resources Board Providence, Rhode Island 1985 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WILLIAM P. CLARK f Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: Chief, Rhode Island Office Open-File Services Section U.S. Geological Survey Western Distribution Branch Room 237 U.S. Geological Survey John 0. Pastore Federal Bldg. Box 25425, Federal Center Providence, RI 02903 Denver, CO 80225 (Telephone: (401) 528-5135) (Telephone: (308) 234-5888) CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 3 Purpose and scope 7 Previous studies 7 Acknowledgments 8 Water use 8 Hydrology 10 Streamflow 10 Duration of streamflow 12 Frequency and duration of low flow 12 Components of streamflow 16 Relation of runoff to geology and topography 17 Hydrogeology 20 Bedrock 26 Till 27 Stratified drift 28 Storage coefficient and specific yield 29 Hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity -

HOUSING ELEMENT Effective 2007-2014 INTRODUCTION GENERAL PLAN ELEMENTS PLAN GENERAL HOUSING

HISTORIC OVERVIEW HOUSING ELEMENT Effective 2007-2014 INTRODUCTION GENERAL PLAN ELEMENTS HOUSING “There’s no place like home.” —Dorothy Introduction....................................................................................................................................262 Housing.Needs.Assessment.....................................................................................................266 APPENDICES Inventory.of.Undeveloped.Lands..........................................................................................284 Potential.Affordable.Housing.Sites.......................................................................................286 Housing.Development.Constraints......................................................................................287 The.Housing.Program.................................................................................................................302 Goal.H1,.Policies,.and.Strategies............................................................................................305 Goal.H2,.Policies,.and.Strategies............................................................................................306 Goal.H3,.Policies,.and.Strategies............................................................................................308 AREA PLANS Goal.H4,.Policies,.and.Strategies............................................................................................311 Goal.H5,.Policies,.and.Strategies............................................................................................313