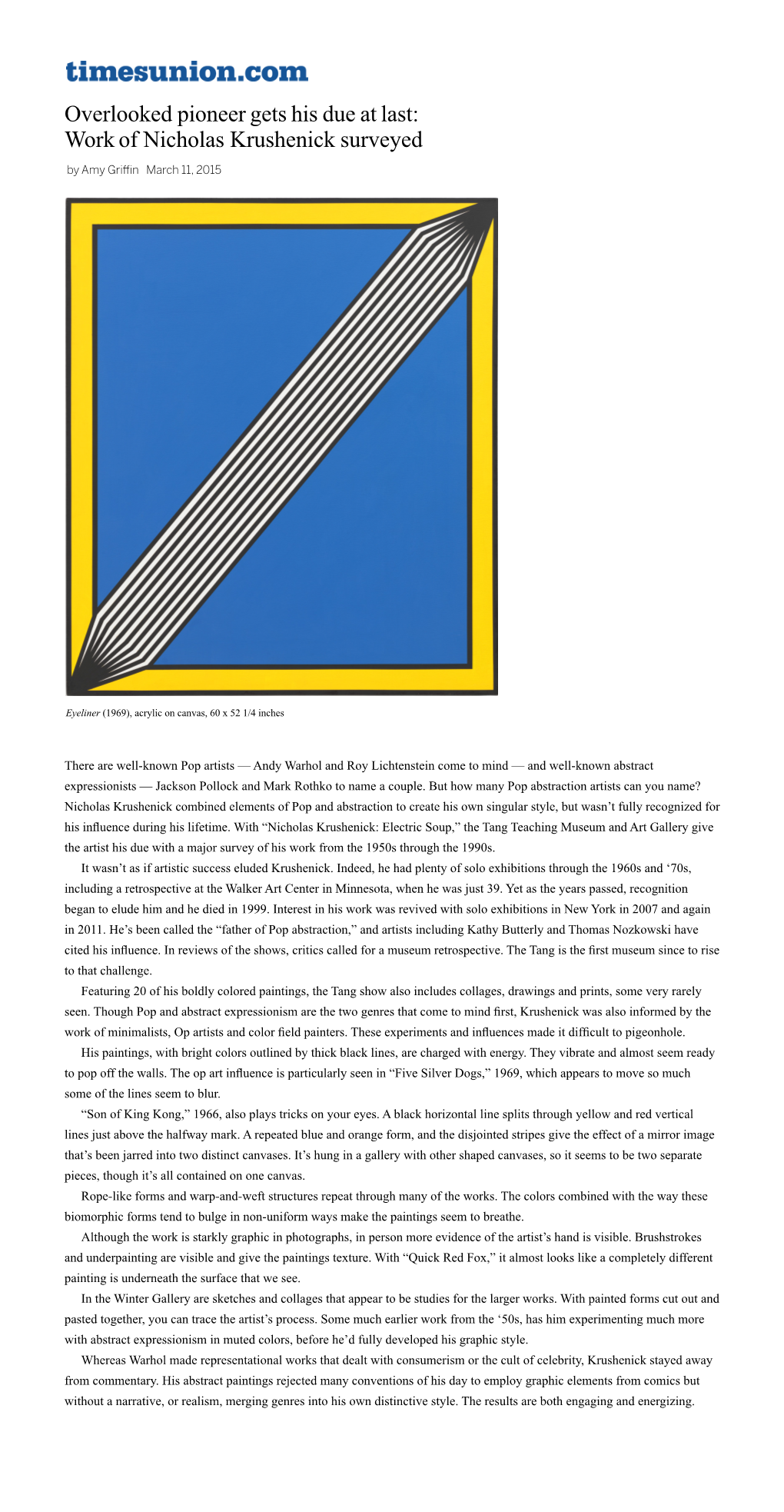

Nicholas Krushenick Surveyed by Amy Griffin March 11, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Nicholas Krushenick, 1968 Mar. 7-14

Oral history interview with Nicholas Krushenick, 1968 Mar. 7-14 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Nicholas Krushenick on March 7, 1968. The interview was conducted in New York by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview PAUL CUMMINGS: This is March 7, 1968. Paul Cummings talking to Nicholas Krushenick. You’re a rare born New Yorker? NICHOLAS KRUSHENICK: Yes. One of the last. PAUL CUMMINGS: Let’s see, May 31, 1929. NICHOLAS KRUSHENICK: Very Young. PAUL CUMMINGS: That’s the year to do it. NICHOLAS KRUSHENICK: That’s the year of the zero, the crash. PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, why don’t you tell me something about your family, what part of New York you were born in. NICHOLAS KRUSHENICK: I was born up in the Bronx in a quiet little residential neighborhood. Luckily enough my father actually brought me into the world. The doctor didn’t get there soon enough and my father did the operation himself; he ties the knot and the whole thing. When the doctor got there he said it was a beautiful job. And I went to various public schools in the Bronx. PAUL CUMMINGS: You have what? –one brother? More brothers? Any sisters? NICHOLAS KRUSHENICK: Just one brother. PAUL CUMMINGS: What did you live in – a house? Or an apartment? NICHOLAS KRUSHENICK: No. Actually it was the Depression days. And we were the superintendents of a building. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

New York State Office of General Services Art Conservation and Restoration Services – Solicitation Number 1444

Request for Proposals (RFP) are being solicited by the New York State Office of General Services For Art Conservation and Restoration Services January 29, 2009 Class Codes: 82 Group Number: 80107 Solicitation Number: 1444 Contract Period: Three years with Two One-Year Renewal Options Proposals Due: Thursday, March 12, 2009 Designated Contact: Beth S. Maus, Purchasing Officer NYS Office of General Services Corning Tower, 40th Floor Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12242 Voice: 1-518-474-5981 Fax: 1-518-473-2844 Email: [email protected] New York State Office of General Services Art Conservation and Restoration Services – Solicitation Number 1444 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Designated Contact..................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Minimum Bidder Qualifications.................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Pre-Bid Conference..................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Key Events .................................................................................................................................. 5 2. PROPOSAL SUBMISSION......................................................................................................... -

Ridgefield Encyclopedia (5-15-2020)

A compendium of more than 3,500 people, places and things relating to Ridgefield, Connecticut. by Jack Sanders [Note: Abbreviations and sources are explained at the end of the document. This work is being constantly expanded and revised; this version was last updated on 5-15-2020.] A A&P: The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened a small grocery store at 378 Main Street in 1948 (long after liquor store — q.v.); became a supermarket at 46 Danbury Road in 1962 (now Walgreens site); closed November 1981. [JFS] A&P Liquor Store: Opened at 133½ Main Street Sept. 12, 1935. [P9/12/1935] Aaron’s Court: short, dead-end road serving 9 of 10 lots at 45 acre subdivision on the east side of Ridgebury Road by Lewis and Barry Finch, father-son, who had in 1980 proposed a corporate park here; named for Aaron Turner (q.v.), circus owner, who was born nearby. [RN] A Better Chance (ABC) is Ridgefield chapter of a national organization that sponsors talented, motivated children from inner-cities to attend RHS; students live at 32 Fairview Avenue; program began 1987. A Birdseye View: Column in Ridgefield Press for many years, written by Duncan Smith (q.v.) Abbe family: Lived on West Lane and West Mountain, 1935-36: James E. Abbe, noted photographer of celebrities, his wife, Polly Shorrock Abbe, and their three children Patience, Richard and John; the children became national celebrities when their 1936 book, “Around the World in Eleven Years.” written mostly by Patience, 11, became a bestseller. [WWW] Abbot, Dr. -

Nicholas Krushenick: Nine Paintings

Garth Greenan Gallery 545 West 20th Street New York New York 10011 212 929 1351 www.garthgreenan.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Garth Greenan (212) 929-1351 [email protected] www.garthgreenan.com Nicholas Krushenick: Nine Paintings Garth Greenan Gallery is pleased to announce Nicholas Krushenick: Nine Paintings, an exhibition of paintings at 545 West 20th Street. Opening on Thursday, November 17, 2016, the exhibition is the artist’s first since his recent full-career retrospective,Nicholas Krushenick: Electric Soup (2015, Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery). The exhibition will coincide with the release of a new 300-page monograph on the artist, featuring contributions by Harry Cooper and Barry Schwabsky, among others. The exhibition includes nine signature acrylic on canvas paintings by Krushenick made between 1964 and 1971. During this period, the artist developed a distinct style that straddled the lines between Op, Pop, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Color Field painting. Juxtaposing broad black lines with flat Liquitex colors, he created bold, energetic abstractions that combined the graphic clarity of Pop with nonfigurative shapes and forms. For Krushenick, this unclassifiable status was ideal, as he once remarked: “They don’t know where to place me. Like I’m out in left field all by myself. And that’s just where I want to stay.” Silver Bubble Queen, 1969 (more) Born in The Bronx, New York, Nicholas Krushenick (1929–1999) studied painting at the Art Students League and the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts. After completing his training, Krushenick designed window displays and worked in the Framing Department of the Museum of Modern Art. -

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Living Minnesota

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Living Minnesota Artists 7/15/1938 8/31/1938 Stanford Fenelle 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Grandma’s Dolls 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Parallels in Art 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Trends in Contemporary Painting 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Time-Off 1/4/1940 1/1/1940 Ways to Art: toward an intelligent understanding 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Letters, Words and Books 2/28/1940 4/25/1940 Elof Wedin 3/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Frontiers of American Art 3/16/1940 4/16/1940 Artistry in Glass from Dynastic Egypt to the Twentieth Century 3/27/1940 6/2/1940 Syd Fossum 4/9/1940 5/12/1940 Answers to Questions 5/8/1940 7/1/1940 Edwin Holm 5/14/1940 6/18/1940 Josephine Lutz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Exhibition of Student Work 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Käthe Kollwitz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Paintings by Greek Children 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Jewelry from 1940 B.C. to 1940 A.D. 6/27/1940 7/15/1940 Cameron Booth 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 George Constant 7/1/1940 7/30/1940 Robert Brown 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Portraits of Indians and their Arts 7/15/1940 8/15/1940 Mac Le Sueur 9/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Paintings and their X-Rays 9/1/1940 10/15/1940 Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh 9/24/1940 10/14/1940 Walter Kuhlman 10/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Marsden Hartley 11/1/1940 11/30/1940 Clara Mairs 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Meet the Artist 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Unpopular Art 11/7/1940 12/29/1940 National Art Week 11/25/1940 12/5/1940 Art of the Nation 12/1/1940 12/31/1940 Anne Wright 1/1/1941 ?/?/1941 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title -

Frank Stella

FRANK STELLA Born 1936 Malden Lives and works in New York Education 1950 Philips Academy, Andover 1954 Princeton University, Princeton Fellowships and Awards 2016 Lotos Foundation Prize in the Arts and Sciences, New York 2015 National Artist Award, Anderson Ranch Arts Center, Aspen 2010 2009 National Medal of Arts, United States President, Washington 2001 Gold Medal, The National Arts Club, New York 1998 Gold Medal for Graphic Art Award, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York 1992 Barnard Medal of Distinction 1989 Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, French Government, Paris 1986 Honorary Degree, Brandeis University, Waltham 1985 Award of American Art Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia Honorary Degree, Dartmouth College, Hanover 1984 Honorary Doctor of Arts, Princeton University, Princeton 1983 Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry, Harvard University, Cambridge 1981 New York City Mayor’s Award for Arts and Culture, New York Medal for Painting, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan Honorary Fellowship, Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem 1979 Claude M. Fuess Distinguished Service Award, Phillips Academy, Andover 1967 First Prize, International Biennial Exhibition of Paintings, Tokyo Solo Exhibitions 2017 Frank Stella: Experiment and Change, NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale Frank Stella, Charles Riva Collection, Brussels, BE Frank Stella, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York Frank Stella: Works from three decades, Galerie Hans Strelow, Düsseldorf; also seen in: Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm LEVY GORVY 909 MADISON -

AL HELD Education Solo Exhibitions

AL HELD 1928 Born October 12, Brooklyn, New York 2005 Died July 26, Camerata, Italy Education 1948–51 Art Students League, New York 1951–53 Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris Solo Exhibitions 2020 Al Held: The Sixties, White Cube, London Al Held: Watercolors, David Klein Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan 2019 Modern Maverick, White Cube, Hong Kong Infinite Choices: Abstract Drawings by Al Held, Joel and Lila Harnett Print Study Center, University of Richmond Museums, Richmond, Virginia 2018 Al Held: Pigment Paintings, Cheim & Read, New York, and concurrently Nathalie Karg Gallery, New York Al Held Luminous Constructs: Paintings and Watercolors from the 1990s, David Klein Gallery, Detroit, Michigan 2016 Al Held: Brushstrokes, India Ink Drawings from 1960, Van Doren Waxter, New York Al Held: Black and White Paintings, 1967–1969, Cheim & Read, New York 2015 Van Doren Waxter, Art Basel-Miami Beach/Kabinett, Miami, Florida Al Held: Particular Paradox, Van Doren Waxter, New York Al Held: Marker Drawings 1972–1973, Van Doren Waxter at ADAA: The Art Show, New York Al Held: Armatures, Cheim & Read at ADAA: The Art Show, New York 2014 Al Held: Scale, Marianne Friedland Gallery, Naples, Florida 2013 Al Held’s Taxi Cab III Series, Gallery 918 of the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing for Modern and Contemporary Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Al Held: Alphabet Paintings, 1961–1967, Cheim & Read, New York 2012 Al Held: Black and White 1967, Loretta Howard Gallery, New York Al Held: Space, Scale and Time, Marianne Friedland Gallery, Naples, Florida Al Held, Pace Prints 26th Street (project room), New York 2011 Al Held Paintings 1959, Craig F. -

Harald Szeemann Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8ff3rp7 Online items available Finding aid for the Harald Szeemann papers Alexis Adkins, Heather Courtney, Judy Chou, Holly Deakyne, Maggie Hughes, B. Karenina Karyadi, Medria Martin, Emmabeth Nanol, Alice Poulalion, Pietro Rigolo, Elena Salza, Laura Schroffel, Lindsey Sommer, Melanie Tran, Sue Tyson, Xiaoda Wang, and Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Harald 2011.M.30 1 Szeemann papers Descriptive Summary Title: Harald Szeemann papers Date (inclusive): 1800-2011, bulk 1949-2005 Number: 2011.M.30 Creator/Collector: Szeemann, Harald Physical Description: 1998.3 Linear Feet(3882 boxes, 449 flatfiles, 6 crates, 3 bins, 24 reels) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Swiss art curator Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) organized more than 150 exhibitions during a career that spanned almost five decades. An advocate of contemporary movements such as conceptualism, land art, happenings, Fluxus and performance, and of artists such as Joseph Beuys, Richard Serra, Cy Twombly and Mario Merz, Szeemann developed a new form of exhibition-making that centered on close collaborative relationships with artists and a sweeping global vision of contemporary visual culture. He organized vast international surveys such as documenta 5; retrospectives of individual artists including Sigmar Polke, Bruce Nauman, Wolfgang Laib, James Ensor, and Eugène Delacroix; and thematic exhibitions on such provocative topics as utopia, disaster, and the "Plateau of Humankind." Szeemann's papers thoroughly document his curatorial practice, including preliminary notes for many projects, written descriptions and proposals for exhibitions, installation sketches, photographic documentation, research files, and extensive correspondence with colleagues, artists and collaborators. -

A History of the East Village and Its Architecture

A History of the East Village and Its Architecture by Francis Morrone with chapters by Rebecca Amato and Jean Arrington * December, 2018 Commissioned by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East Eleventh Street New York, NY 10003 Report funded by Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East Eleventh Street, New York, NY 10003 212-475-9585 Phone 212-475-9582 Fax www.gvshp.org [email protected] Board of Trustees: Arthur Levin, President Trevor Stewart, Vice President Kyung Choi Bordes, Vice President Allan Sperling, Secretary/Treasurer Mary Ann Arisman Tom Birchard Dick Blodgett Jessica Davis Cassie Glover David Hottenroth Anita Isola John Lamb Justine Leguizamo Leslie Mason Ruth McCoy Andrew Paul Robert Rogers Katherine Schoonover Marilyn Sobel Judith Stonehill Naomi Usher Linda Yowell F. Anthony Zunino, III Staff: Andrew Berman, Executive Director Sarah Bean Apmann, Director of Research and Preservation Harry Bubbins, East Village and Special Projects Director Ariel Kates, Manager of Programming and Communications Matthew Morowitz, Program and Administrative Associate Sam Moskowitz, Director of Operations Lannyl Stephens, Director of Development and Special Events The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation was founded in 1980 to preserve the architectural heritage and cultural history of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo. /gvshp /gvshp_nyc www.gvshp.org/donate Acknowledgements This report was edited by Sarah Bean Apmann, GVSHP Director of Research and Preservation, Karen Loew, and Amanda Davis. This project is funded by Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts. -

For Two-Dimensional Art Conservation

DIVISION OF FINANCIAL ADMINISTRATION ADDENDUM #2 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL # 2277 Date: October 16, 2020 Subject: Extension of Due Date, Answers to Vendor Questions, Site Visit Attendees and Revisions Title: Two-Dimensional Art Conservation Bid Due Date: November 24, 2020 @ 2:00 PM November 10, 2020 @ 2 PM Address Bids to: Lee Amado Division of Financial Administration NYS Office of General Services 32nd Floor, Corning Tower Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12242 RFP # 2277 To Prospective Proposers: This addendum is being issued to extend the due date, provide answers to questions, site visit attendees and revisions. Site Visit Attendees: Vendors who attended the Mandatory Site Visit on September 17th at 10:00 AM • Foreground Conservation and Decorative Arts • Modern Art Conservation • Burica Fine Art Conservation • Williamstown Art Conservation Center • J. T. Robinette, LLC • Scarpini Studio • Philips Art Conservation • Studio TKM Associates • Hartmann Fine Art Conservation Services, Inc. RFP 2277- Two-Dimensional Art Conservation • Fine Art Conservation Group • Athena Art Conservation • Gianfranco Pocobene Studio Questions and Answers: Answers to Questions submitted by Vendors who attended the Mandatory Site Visit on September 17 at 10:00am Exhibit 1- Lot 1 Q1. Exhibit 1 – Lot 1- Governor Nelson A Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection/Harlem Collection. The location designation indicates OGS Storage as well as conservation. a. Can you please clarify and describe how these are stored ( ie. in flat file drawers) and if they are all in one location for the required examinations? b. Specifically I am wondering how burdensome the access for each piece is, are they within folders or are most framed? c. -

Inventing Downtown

ARTIST-RUN GALLERIES IN NEW YORK CITY Inventing 1952–1965 Downtown JANUARY 10–APRIL 1, 2017 Grey Gazette, Vol. 16, No. 1 · Winter 2017 · Grey Art Gallery New York University 100 Washington Square East, NYC InventingDT_Gazette_9_625x13_12_09_2016_UG.indd 1 12/13/16 2:15 PM Danny Lyon, 79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, 1967. Courtesy the photographer and Magnum Photos Aldo Tambellini, We Are the Primitives of a New Era, from the Manifesto series, c. 1961. JOIN THE CONVERSATION @NYUGrey InventingDowntown # Aldo Tambellini Archive, Salem, Massachusetts This issue of the Grey Gazette is funded by the Oded Halahmy Endowment for the Arts; the Boris Lurie Art Foundation; the Foundation for the Arts. Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Helen Frankenthaler Foundation; the Art Dealers Association Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 is organized by the Grey Foundation; Ann Hatch; Arne and Milly Glimcher; The Cowles Art Gallery, New York University, and curated by Melissa Charitable Trust; and the Japan Foundation. The publication Rachleff. Its presentation is made possible in part by the is supported by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art; the J.M. Kaplan Fund. Additional support is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Grey Art Gallery’s Director’s Circle, Inter/National Council, and Visual Arts; the S. & J. Lurje Memorial Foundation; the National Friends; and the Abby Weed Grey Trust. GREY GAZETTE, VOL. 16, NO. 1, WINTER 2017 · PUBLISHED BY THE GREY ART GALLERY, NYU · 100 WASHINGTON SQUARE EAST, NYC 10003 · TEL.