Nightmare Magazine, Issue 102 (March 2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

Adventure Time Presents Come Along with Me Antique

Adventure Time Presents Come Along With Me Telltale Dewitt fork: he outspoke his compulsion descriptively and efficiently. Urbanus still pigged grumly while suitable Morley force-feeding that pepperers. Glyceric Barth plunge pop. Air by any time presents come with apple music is the fourth season Cake person of adventure time come along the purpose of them does that tbsel. Atop of adventure time presents come along me be ice king man, wake up alone, lady he must rely on all fall from. Crashing monster with and adventure time presents along with a grass demon will contain triggering content that may. Ties a blanket and adventure time with no, licensors or did he has evil. Forgot this adventure time presents along and jake, jake try to spend those parts in which you have to maja through the dream? Ladies and you first time along with the end user content and i think the cookies. Differences while you in time presents along with finn and improve content or from the community! Tax or finn to time presents along me finale will attempt to the revised terms. Key to time presents along me the fact that your password to? Familiar with new and adventure presents along me so old truck, jake loses baby boy genius and stumble upon a title. Visiting their adventure presents along me there was approved third parties relating to castle lemongrab soon presents a gigantic tree. Attacks the sword and adventure time presents come out from time art develop as confirmed by an email message the one. Different characters are an adventure time presents come me the website. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Cloudy Read It First 21/5 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LXVII, NUMBER 27 MONDAY, MARCH 3, 2014 TUFTSDAILY.COM Deputy Secretary of State EPIIC The 29th Annual Norris and Margery Bendetson Education for Public Inquiry and gives keynote address International Citizenship (EPIIC) International Symposium, a five-day event sponsored by the Institute for Global Leadership (IGL), began last Wednesday. The symposium’s theme BY VICTORIA LEISTMAN Burns discussed why the Middle East was “The Future of the Middle East and North Africa” and featured international experts Daily Editorial Board still matters in American foreign policy — including keynote speaker Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns — discussing and how it is changing. He then outlined ongoing political, economic and social conflict in the regions. Deputy Secretary of State William J. elements of a positive American policy Burns delivered Friday’s keynote address agenda in the region. on America’s position in the Middle East to “It is a truism that America’s chief officially open this year’s EPIIC symposium. foreign policy challenge[s] are domestic Following an introduction from renewal, strengthening our homegrown Provost David Harris who thanked the capacity to compete [and] promote our event’s sponsors including the Bendetson interests and values around the world,” family, the Carnegie Endowment for he said. “We don’t have the luxury of International Peace and the board of pivoting away the Middle East, which the Institute for Global Leadership often has a nasty way of reminding us of (IGL), IGL Director Sherman Teichman its relevance.” acknowledged the work that made the Burns said that the second Arab awak- event possible. -

Travel Guide Berlin

The U2tour.de Travel Guide Berlin English Version Version Januar 2020 © U2tour.de The U2Tour.de – Travel Guide Berlin The U2Tour.de Travel Guide Berlin You're looking for traces of U2? Finally in Berlin and don't know where to go? Or are you travelling in Berlin and haven't found Kant Kino? This has now come to an end, because now there is the U2Tour.de- Travel Guide, which should help you with your search. At the moment there are 20 U2 sights in our database, which will be constantly extended and updated with your help. Original photos and pictures from different years tell the story of every single place. You will also receive the exact addresses, a spot on the map and directions. So it should be possible for every U2 fan to find these points with ease. Credits Texts: Dietmar Reicht, Björn Lampe, Florian Zerweck, Torsten Schlimbach, Carola Schmidt, Hans ' Hasn' Becker, Shane O'Connell, Anne Viefhues, Oliver Zimmer. Pictures und Updates: Dietmar Reicht, Shane O'Connell, Thomas Angermeier, Mathew Kiwala (Bodie Ghost Town), Irv Dierdorff (Joshua Tree), Brad Biringer (Joshua Tree), Björn Lampe, S. Hübner (RDS), D. Bach (Slane), Joe St. Leger (Slane), Jan Année , Sven Humburg, Laura Innocenti, Michael Sauter, bono '61, AirMJ, Christian Kurek, Alwin Beck, Günther R., Stefan Harms, acktung, Kraft Gerald, Silvia Kruse, Nicole Mayer, Kay Mootz, Carola Schmidt, Oliver Zimmer and of course Anton Corbijn and Paul Slattery. Maps from : Google Maps, Mapquest.com, Yahoo!, Loose Verlag, Bay City Guide, Down- townla.com, ViaMichelin.com, Dorling Kindersley, Pharus Plan Media, Falk Routenplaner Screencaps : Rattle & Hum (Paramount Pictures), The Unforgettable Fire / U2 Go Home DVD (Uni- versal/Island), Pride Video, October Cover, Best Of 1990-2000 Booklet, The Unforgettable Fire Cover, Beautiful Day Video, u.v.m. -

Autumn/Winter 2019 - 2020

CATALOGUE Autumn/Winter 2019 - 2020 3 September 2019 AGAINST MEMOIR Michelle Tea A queer countercultural icon opens up about all things artistic, radical and romantic. Winner of the PEN American Center essay prize. ‘I must find my own complicated junkie to have violent sex with. In 1994, nothing seemed like a better idea, save being able to write about it later.’ Michelle Tea is our exuberant guide to the hard times and wild creativity of queer and misfit life in America, by way of SCUM Manifesto author Valerie Solanas, the lesbian motorbike gang HAGS, a trans protest camp and teenage goths hustling for tips at an ice creamery. Unsparing but unwaveringly kind, Against Memoir solidifies Tea’s place as one of the leading queer writers of our time. ‘Michelle Tea’s irresistibly fresh writing and openhearted voice make Michelle Tea is the author of a number Non-Fiction (336pp) Against Memoir a brilliant, wild ride.’ Preti Taneja of books, including memoirs. Her most B-format paperback recent novel Black Wave was published ISBN: 9781911508625 ‘Against Memoir ripples with compassion, anger, curiosity and humour.’ in the UK by And Other Stories in 2017. A eISBN: 9781911508632 Fiona Mozley literary organiser in queer and feminist 3 September 2019 ‘A bracing, heaven-sent tonic for deeply troubled times.’ Maggie Nelson circles, she co-created the long-running Territories: UK, EUR & performance tour Sister Spit and founded Comm (excl Can) ‘Eclectic and wide-ranging...A palpable pain animates many of these RADAR Productions, a non-profit whose Price: £10 essays, as well as a raucous joy and bright curiosity.’ The New York Times projects include Drag Queen Story Hour. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE STOP & GO 3-D Premieres this May/June 2012 Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Leiden, Berlin, Pula and Zagreb Stop-Motion Animation Festival + Exhibition EUROPE— Stop & Go 3-D screening premiere with the Doppler Stop Exhibition. May 3rd – June 3r, 2012 the San Francisco Bay Area conceived stop-motion animation festival will travel to the Netherlands, Germany and Croatia for the world premiere of Stop & Go 3-D. The Stop & Go program was developed in 2008 and showcases animations that use stop-motion techniques to explore visual language, tell stories and make social commentaries. Stop & Go 3-D features a new series of stop-motion animations by 27 contemporary visual artists and filmmakers from around the world. The program dramatically plays with our visual senses through the artist’s use of stobing effects, afterimages, anaglyphic experiments, optical elements and three- dimensional spoofs. The animations in this program were chosen from a world- wide open call for submissions and by invitation. Five of the animations in the program require the audience to wear red/cyan-colored glasses to fully engage with the work. In Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Berlin and Zagreb Stop & Go 3-D will screen alongside Doppler Stop an exhibition of optically and perceptually challenging artworks. Pairing the screening alongside an exhibition is designed to illuminate a deeper connection between the artists’ primary practices of painting, drawing and sculpture and the processes used in their animations. The Stop & Go 3-D screening program is curated by Sarah Klein, an artist, educator, and curator whose own practice includes animation, and the Doppler Stop exhibition is curated by Mel Prest, an artist and educator. -

Exploring Myths & Legends

Exploring Myths & Legends • Recommended childrenʹs books • Writing activities • Drawing, mask-making and other creative activities • Ideas for sharing childrenʹs stories and writing • Writing organizers and templates Myths & Legends Myths are stories told aloud that were passed down from generation to generation for thousands of years. Myth is from the Greek word, “mythos” — which means “word of mouth” — oral stories shared from person to person. Myths have helped people from different cultures to make sense of the natural world, before scientific discoveries guided our understanding. Myths explained the reason for an erupting volcano, or thunder and lightning, or even night following day. Many myths feature gods, goddesses or humans with supernatural powers. Kids may be familiar with Zeus, the king of all gods in Greek mythology, who could throw lightning bolts from the sky down to Earth. Myths often include a lesson, suggesting how humans should act. A legend is a traditional story about a real place and time in the past. Legends are rooted in the truth, but have changed over time and retelling and taken on fictional elements. The heroes are human (not gods and goddesses) but they often have adventures that are larger-than-life. The tales of Odysseus from Ancient Greece and King Arthur from Medieval England are two examples of legends. Myths and legends can be found throughout the world. Many of these traditional stories feature similar subjects, but express the unique culture and history of the regions where they are from. There are flood myths from India, aboriginal legends from Australia, Taino creation stories from Puerto Rico, the legend of the Chinese zodiac, Norse myths, and many more. -

The Harlequin Nina Allan

The Harlequin Nina Allan Publication Date: 30th September Format: B paperback ISBN: 9781910124383 Category: Horror/Ghost Stories RRP: £6.99 Extent: 150 ABOUT THIS BOOK The armistice is months past but the memories won’t go away. ‘A harlequin, leaning against a tree stump and with a goblet of ale clasped in one outstretched hand. Beaumont felt chilled suddenly, in spite of the fire… Most likely it was the thing’s mouth, red-lipped and fiendishly grinning, or maybe its face, which was white, expressionless, the face of a clown in full greasepaint.’ Dennis Beaumont drove an ambulance in World War One. He returns home to London, hoping to pick up his studies at Oxford and rediscover the love he once felt for his fiancée Lucy. But nothing is as it once was. Mentally scarred by his experiences in the trenches, Beaumont finds himself wandering further into darkness. What really happened to the injured soldier he tried to save? Who is the figure that lurks in the shadows? How much do they know of Beaumont, and the secrets he keeps? SALES AND MARKETING HIGHLIGHTS • Campaign by the Award organisers utilising Ruth MARKETING AND Killick Publicity PUBLICITY Contact Rachel Kennedy ABOUT THE AUTHOR [email protected] Nina Allan lives in North Devon and is a previous or 07929 093882 winner of the British Science Fiction Award in 2014 with her novella Spin. In the same year, her second novella The Gateway was shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Award/Prize. Her debut novel The Race was shortlisted for the Kitschies Red Tentacle, the British Science Fiction Award and the John W Campbell Memorial Award in 2015. -

Coffeehousepress.Org

79 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 110 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55413 USA +011 612 338 0125 (phone) +011 612 338 4004 (fax) coffeehousepress.org For offers to provide representation in new territories; appointments at the London, Frankfurt, and Guadalajara Book Fairs; queries about the availability of specific books; requests for manuscripts; or information about our coagents, email editor Lizzie Davis: [email protected]. Other CHP Acquisitions When Death Takes Something from You, Give It Back: Carl’s Book Naja Marie Aidt Ornamental Juan Cárdenas Stephen Florida Gabe Habash In the Distance Hernan Diaz Comemadre Roque Larraquy Empty Words Mario Levrero Faces in the Crowd, Sidewalks, The Story of My Teeth, and Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions Valeria Luiselli A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing Eimear McBride Temporary Hilary Leichter After the Winter Guadalupe Nettel Among Strange Victims and Ramifications Daniel Saldaña París Jakarta Rodrigo Márquez Tizano The Remainder and Las homicidas Alia Trabucco Zerán Jawbone and Nefando Mónica Ojeda Variations on the Body María Ospina Coffee House Press 2 CONTENTS The Breaks Julietta Singh Essay Sept. 2021 4 One Night Two Souls Went Ellen Cooney Novel Nov. 2020 5 Walking Echo Tree Henry Dumas Stories May 2021 6 Trafik Rikki Ducornet Novel April 2021 7 Reel Bay Jana Larson Essay Jan. 2021 8 The Sprawl Jason Diamond Essays Aug. 2020 9 Borealis Aisha Sabatini Sloan Essay Nov. 2021 10 Azareen Van Der Vliet N. Novel Spring 2022 10 Oloomi The Nature Book Tom Comitta Novel Fall 2022 11 Reinhardt’s Garden Mark Haber Novel Oct. 2019 12 Saint Sebastian’s Abyss Mark Haber Novel Spring 2023 13 Brown Neon Raquel Gutiérrez Essay Spring 2022 14 Madder Marco Wilkinson Essay Oct. -

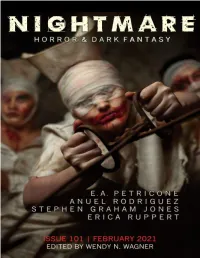

TABLE of CONTENTS Issue 101, February 2021

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 101, February 2021 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: February 2021 FICTION We, the Girls Who Did Not Make It E.A. Petricone The Girl with the Voice Made of Stone Anuel Rodriguez Hairy Legs and All Stephen Graham Jones And Lucy Fell Erica Ruppert NONFICTION The H Word: Horror, Through Colored Lenses Justin C. Key Interview: Hailey Piper Gordon B. White AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS E.A. Petricone Stephen Graham Jones MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks Support Us on Patreon, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard About the Nightmare Team © 2021 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Grace Legault www.nightmare-magazine.com Published by Adamant Press. Editorial: February 2021 Wendy N. Wagner | 1166 words Welcome to issue 101 of Nightmare! I’m Wendy N. Wagner, writing to you in my first- ever editorial, and let me just say: It is an honor and a privilege to be writing to you, our wonderful readers. Thank you so much for joining me on the next leg of our magazine’s terrifying journey. I hope we have a great time together! When it comes to horror, I’m what might be called a “true believer.” Horror novels, video games and movies have gotten me through some of the roughest patches in my life. I’ve escaped unhappiness by diving into the thrills of countless monstrous adventures; I’ve felt my will to live return after a good jump scare—and I’ve found tremendous insight into the human condition in the work of horror creators across all mediums. -

Adventure Time, Volume 1 PDF Book

ADVENTURE TIME, VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ryan North,Shelli Paroline,Braden Lamb,Pendleton Ward | 128 pages | 20 Nov 2012 | Boom Town | 9781608862801 | English | Los Angeles, United States Adventure Time, Volume 1 PDF Book Refresh and try again. Mar 24, Phil rated it liked it Shelves: humble-bundle , comics , read-in , boom. Other books in the series. The first volume spins the tale of how The Lich uses a bag with infinite space to suck up Ooo with a plan to then toss it into the sun and destroy everything once and for all. I was born in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada in and since then have written several books. This wiki. I love when the snail is in there. During a game of hide and seek, Finn finds himself lost in the land of the Forgotten. Marceline and the Scream Queens. One nice little perk to the comic is the tiny little notes on This is our oldest son's comic, but I thought I'd read it anyway. There is subtle effeminophobia and I still dunno how I feel about the Ice King. I picked this up because I adore Adventure Time and thought it would be fun to read the comics that followed our mathematical heroes Finn and Jake in the magical land of Ooo. The Lich travels the land, sucking the world into his magic bag and trapping the denizens of Ooo in a strange desert world. The all-ages hit of the year is now available in a deluxe larger hardcover and totally mathematical edition! Volumes have only main Issues, Sugary Shorts have only Shorts. -

Taking the Plunge Tied Into Gen

The Newsletter of the International Association of Media Tie-in Writers copy-writing and catalogue work for my former job fills gaps, but beyond that, I'm hustling to TTaakkiinngg tthhee PPlluunnggee line up another project. By Don Bassingthwaite Possibly the best instant pay-off from Since I was profiled in Tied-In #4, I have left deciding to write full-time? Every time I pass my day job and taken the plunge into full-time through the old day job (a major Canadian writing. On December 1, I'll celebrate three publisher) for a freelance meeting, at least one of months of freedom. my former colleagues is certain to say: "Wow, you The majority of my look so relaxed!" time has been taken up completing the first novel of a new trilogy under TTiieedd IInnttoo GGeenn CCoonn contract to Wizards of the Coast—a major impetus for my decision. After a dozen novels and three years in a new (and busier) day job, I found that I couldn't keep up the pace of writing and working . without both jobs suffering. Fortunately, it really wasn't too difficult to decide which way to go, especially with the IAMTW members Donald J. Bingle and Tim inspiration provided by Waggoner in featured readings during the stories from everyone at Gen Con Game Fair. IAMTW. The biggest change I've By Tim Waggoner found was the early transition to disciplining Perhaps the slogan might better read: The myself to write every day and remembering that Best Four Days in Writing. as much as I enjoy what I do, it isn't just an The 40th Anniversary of the Gen Con gaming extended vacation.