Friendship Understanding in Males and Females on the Autism Spectrum and Their Typically Developing Peers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study Guide by Marguerite O Lhara

A STUDY GUIDE BY MArguerite o ’hARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Introduction > Mary and Max is an animated feature film from the creators of the Academy Award-winning short animation Harvie Krumpet (Adam Elliot, 2003). This is Adam Elliot’s first full-length feature film. LikeHarvie , it is an animated film with claymation characters. However, unlike many animated feature films, it is minimal in its use of colour and the action does not revolve around kooky creatures with human voices and super skills. Mary and Max is about the lives of two people who become pen pals, from opposite sides of the world. Like Harvie Krumpet, Mary and Max is innocent but not naive, as it takes us on a journey that explores friendship and autism as well as taxidermy, psychiatry, alcoholism, where babies come from, obesity, kleptomania, sexual difference, trust, copulating dogs, religious difference, agoraphobia and much more. Synopsis at the Berlin Film festival in the seter, 1995) and WALL·E (Andrew Generation14+ section aimed at Stanton, 2008), will be something HIS IS A TALE of pen- teenagers where it was awarded that many students will find fasci- friendship between two the Jury Special Mention. How- nating. Tvery different people – Mary ever, this is not a film written Dinkle, a chubby, lonely eight-year- specifically for a young audience. It would be enjoyed by middle and old girl living in the suburbs of It is both fascinating and engaging senior secondary students as well Melbourne, and Max Horovitz, a in the way it tells the story of the as tertiary students studying film. -

“I Can LEARN. I Can WORK” Campaign +

Autism-Europe N°74 / April 2021 “I can LEARN. I can WORK” campaign celebrated across the EU and beyond COVID-19 crisis: The situation of autistic people in times of the pandemic New EU Disability Strategy: building a Union without barriers for the next decade The ChildIN project: training chilminders across Europe for inclusion The IVEA project enhances the inclusion of autistic people through employment AE’s Congress 2022: + Join us in Cracow for a “Happy Journey through Life” Funded by the European Union Contents 03 Edito 04 The “I can LEARN. I can WORK” campaign celebrated across the EU and beyond 07 AE governing bodies’ meetings: More than 80 representatives meet virtually 08 New EU Disability Strategy : building a Union without barriers for the next decade Edito 10 Hector Diez, autistic student of physics 12 08 “My suffering in education almost killed my desire to investigate the universe” 12 COVID-19 crisis: The situation of autistic people in times of the pandemic 14 The ChildIN project: training chilminders across Europe for inclusion 16 The IVEA project enhances the inclusion of autistic people through employment 14 18 AE’s Congress 2022: Join us in Cracow for a “Happy Journey through Life” 19 Working, housing and leisure opportunities to promote the autonomy in France 20 Raising awareness and supporting families of autistic youth in Andorra 04 21 Providing innovative support to autistic people and their families in Cyprus 22 Members list More articles at: 16 www.autismeurope.org Collaborators Editorial Committee: Cristina Fernández, Harald Neerland, Zsuzsanna Szilvasy, Marta Roca, Stéfany Bonnot-Briey, Liga Berzina, Tomasz Michałowicz. -

Autism and Aspergers in Popular Australian Cinema Post-2000 | Ellis | Disability Studies Quarterly

Autism and Aspergers in Popular Australian Cinema Post-2000 | Ellis | Disability Studies Quarterly Autism & Aspergers In Popular Australian Cinema Post 2000 Reviewed By Katie Ellis, Murdoch University, E-Mail: [email protected] Australian Cinema is known for its tendency to feature bizarre and extraordinary characters that exist on the margins of mainstream society (O'Regan 1996, 261). While several theorists have noted the prevalence of disability within this national cinema (Ellis 2008; Duncan, Goggin & Newell 2005; Ferrier 2001), an investigation of characters that have autism is largely absent. Although characters may have displayed autistic tendencies or perpetuated misinformed media representations of this condition, it was unusual for Australian films to outright label a character as having autism until recent years. Somersault, The Black Balloon, and Mary & Max are three recent Australian films that explicitly introduce characters with autism or Asperger syndrome. Of the three, the last two depict autism with sensitivity, neither exploiting it for the purposes of the main character's development nor turning it into a spectacle of compensatory super ability. The Black Balloon, in particular, demonstrates the importance of the intentions of the filmmaker in including disability among notions of a diverse Australian community. Somersault. Red Carpet Productions. Directed By Cate Shortland 2004 Australia Using minor characters with disabilities to provide the audience with more insight into the main characters is a common narrative tool in Australian cinema (Ellis 2008, 57). Film is a visual medium that adopts visual methods of storytelling, and impairment has become a part of film language, as another variable of meaning within the shot. -

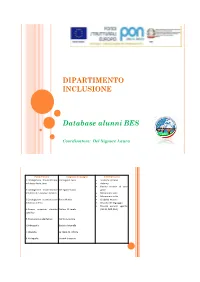

DIPARTIMENTO INCLUSIONE Database Alunni

DIPARTIMENTO INCLUSIONE Database alunni BES Coordinatore: Del Signore Laura Piano di lavoro Insegnanti di sostegno Ambiti di ricerca 1.Catalogazione strumentazione Del Signore Lucia Sindrome di Down nel plesso Paola Sarro Autismo Ritardo mentale di vario 2.Catalogazione strumentazione Del Signore Laura grado nel plesso di S.Giovanni Incarico Minorazione vista Minorazione udito 3.Catalogazione strumentazione Parisi Monica Disabilità motoria nel plesso di Pico Disturbo del linguaggio Disturbi evolutivi specifici 4.Ricerca materiale didattico Gelfusa M. Lorella (ADHD, DOP, DSA) specifico 5.Ricerca personaggi famosi Cerrito Loredana 6.Filmografia Barbera Antonella 7.Sitografia La Starza M. Vittoria 8.Bibliografia Gerardi Giovanna DIPARTIMENTO INCLUSIONE 1. Plesso “Paola Sarro” 2. Plesso di San Giovanni Incarico 3. Plesso di Pico 4. Schede didattiche alunni con disabilità 5. Filmografia sulla disabilità 6. Personaggi famosi con disabilità 7. Sitografia 8. Bibliografia 1. Plesso “Paola Sarro” RISORSE DI PLESSO “PAOLA SARRO” RISORSE STRUTTURALI Laboratorio artistico-espressivo Laboratorio di lettura Laboratorio di informatica Laboratorio musicale Palestra Laboratorio lingua inglese RISORSE MATERIALI DISPONIBILI Strumentazioni Pc Lim Materiale didattico Abaco multibase n.3 Casetta delle figure geometriche Percorso sensoriale Solidi Blocchi logici Tellurio Regoli Globo terrestre Software Erickson Dislessia e trattamento sub lessicale Produzione del testo scritto 1 e 2 Geografia facile 1 e 2 Nel mondo dei numeri e delle operazioni 2 e 3 Recupero in …abilità di scrittura 2 Giocare con le parole Un mare di numeri Decodifica sintattica della frase Risolvere i problemi per immagini Sviluppare le competenze semantico-lessicali Un mare di parole Comprensione e produzione verbale Giochi..amo con la storia Hallo Deutsch: attività per l’apprendimento del tedesco Risorse materiali richieste Abbonamenti riviste Guida didattiche 2. -

The Autism Spectrum Information Booklet

The Autism Spectrum Information Booklet A GUIDE FOR VICTORIAN FAMILIES Contents What is Autism? 2 How is Autism Diagnosed? 4 Acronyms and Glossary 6 Common Questions and Answers 7 What does Amaze do? 11 Funding and Service Options 12 Helpful Websites 14 National Disability Insurance Scheme 16 Suggested Reading 18 This booklet has been compiled by Amaze to provide basic information about autism from a number of perspectives. It is a starting point for people with a recent diagnosis, parents/carers of a newly diagnosed child or adult, agencies, professionals and students learning about the autism spectrum for the first time. Once you have read this information package, contact Amaze if you have any other questions or you require more information. 1 What is Autism? Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that causes substantial impairments in social interaction and communication and is characterised by restrictive and repetitive behaviours and interests. People on the autism spectrum may be affected in the following ways: Social Interaction IN CHILDREN IN CHILDREN May display indifference Does not play with other children Joins in only if adult assists & insists People on the autism spectrum may not appear to be interested in joining in with others, or they may want to join in but not know how. Their attempts to respond to social contact may appear repetitive or odd. Alternatively, they may be ‘too social’, such as showing affection to strangers. In general, people on the autism spectrum often have poor social skills and difficulty understanding unwritten social rules. They often lack understanding of acceptable social behaviour. -

Mongrel Media Presents a Film by Adam Elliot

Mongrel Media Presents A Film by Adam Elliot (92 min., Australia, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Synopsis The opening night selection of the 2009 Sundance Film Festival and in competition at the 2009 Berlin Generation 14plus, MARY AND MAX is a clayography feature film from Academy Award® winning writer/director Adam Elliot and producer Melanie Coombs, featuring the voice talents of Toni Collette, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Barry Humphries and Eric Bana. Spanning 20 years and 2 continents, MARY AND MAX tells of a pen-pal relationship between two very different people: Mary Dinkle (Collette), a chubby, lonely 8-year-old living in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia; and Max Horovitz (Hoffman), a severely obese, 44-year-old Jewish man with Asperger’s Syndrome living in the chaos of New York City. As MARY AND MAX chronicles Mary’s trip from adolescence to adulthood, and Max’s passage from middle to old age, it explores a bond that survives much more than the average friendship’s ups-and-downs. Like Elliot and Coombs’ Oscar® winning animated short HARVIE KRUMPET, MARY AND MAX is both hilarious and poignant as it takes us on a journey that explores friendship, autism, taxidermy, psychiatry, alcoholism, where babies come from, obesity, kleptomania, sexual differences, trust, copulating dogs, religious differences, agoraphobia and many more of life’s surprises. -

Books and Movies About Asperger Syndrome (AS), Marriage, and AS in Women by Eva Mendes, LMHC, NCC Asperger/Autism Specialist and Couple’S Counselor

Books and Movies about Asperger Syndrome (AS), Marriage, and AS In Women by Eva Mendes, LMHC, NCC Asperger/Autism Specialist and Couple’s Counselor Dated: June 2nd, 2014 I often recommend that my clients read a book or two to help on their journey of discovery, learning, healing and happiness. The books are listed in random order. If you have a suggestion to add to this list, please do send me an email at [email protected] Thank you! The list is organized under the following topics: 1. Asperger Syndrome (Autism Spectrum) and Marriage 2. General books on Asperger Syndrome/Autism Spectrum 3. Movies and TV shows on Asperger Syndrome/Autism Spectrum 4. Cognitive Behavioral and Dialectic Behavior Therapy 5. Buddhist thought and philosophy 1. Asperger Syndrome/Autism Spectrum and Marriage: ❏ The Other Half of Asperger Syndrome by Maxine Aston This book is focused on various nonspectrum or NT (neurotypical) spouse perspectives and experience in the AS marriage. Validating narratives of what it means to be with an AS partner. ❏ Aspergers in Love by Maxine Aston This book is based on numerous interviews of couples in an AS marriage or relationship. Also includes strategies for dealing with the difficulties of a neurodiverse marriage. ❏ The Asperger Couple’s Workbook by Maxine Aston One of Maxine’s later books, offers activities, illustrations and worksheets for couples to use in their marriage. ❏ Marriage with Asperger Syndrome: 14 Practical Strategies by Eva Mendes A paper I wrote for couples where one or both partners have AS. I have 14 distinct categories of strategies and behaviors couples can use to create ease and harmony in their marriage or longterm relationships. -

Representing Neurological Difference in Contemporary Autism Novels

MAKAI PÉTER KRISTÓF BRIDGING THE EMPATHY GAP: REPRESENTING NEUROLOGICAL DIFFERENCE IN CONTEMPORARY AUTISM NOVELS Supervisors: Kérchy Anna and Cristian Réka Mónika 2015 University of Szeged Faculty of Arts Doctoral School for Literary Studies Anglophone Literatures and Cultures in Europe and North America programme (2011-2014) - 1 - Dedicated to the loving memory of Gálik Julianna Katalin (1990-2013), and her RuneScape character, Tavarisu B, the best Dungeoneering partner one could ask for. We shall respawn. - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 2 Personal Preface: How I Got Here .................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 1 – Introduction: Literature, Science and The Humanities Meet Autism ....................... 11 Chapter 2 – The Use of Consilient Literary Interpretation in Reading the Autism Novel ........... 27 Chapter 3 – Autism’s Career in Psychology: Lighting Candles in A Dark Maze ........................ 37 Chapter 4 – Autism as Disability: Critical Studies of the Condition ............................................ 53 Chapter 5 – The Travelling Concept of ‘Theory of Mind’ in Philosophy, Psychology, Literary Studies and its Relation to Autism ................................................................................................ 75 Chapter 6 – Contextualising the Autism Novel in Contemporary Culture: Constructing Fascinating Narratives -

2014 and Two in Fall 2014) That Already Incorporate the New Student Learning Outcomes Into the Course (See the COURSE GOALS/LEARNING OUTCOMES Portion of the Syllabus)

FIRST-YEAR SEMINAR REAPPROVAL FORM UNIVERSITY OF MARY WASHINGTON COURSE TITLE: DISABILITY STUDIES: REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE AND FILM SUBMITTED BY: Chris Foss DATE: 11-21-14 RATIONALE. Include short statement addressing how this course meets the FSEM’s basic components and new student learning outcomes (see FSEM call above). This course is the most-taught FSEM in the history of UMW; I have offered 23 different sections of the course since its debut in Spring 2008, including the four most recent sections (two in Spring 2014 and two in Fall 2014) that already incorporate the new student learning outcomes into the course (see the COURSE GOALS/LEARNING OUTCOMES portion of the syllabus). The basic components of a FSEM at UMW have remained the same since the inception of the program, so these have been incorporated into all 23 sections previously taught (see the first paragraph of the COURSE DESCRIPTION portion of the syllabus). This course also features multiple meaningful assignments where both writing and speaking are concerned (see the COURSE ASSIGNMENTS portion of the syllabus). Finally, this course already has incorporated two of the new Canvas modules (CA and CRAAP) into its syllabus/calendar. Please let me know if you have any questions or need any further information. SYLLABUS. Attach a course syllabus. SUBMIT this form and attached syllabus electronically as one document to Dave Stahlman ([email protected]). All submissions must be in electronic form. FIRST-YEAR SEMINAR 100A4 DISABILITY STUDIES: REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE AND FILM FALL 2014 SECTIONS 01 & 02 12:00 & 1:00 MWF COMBS 348 Dr. -

Supporting General Education Teacher's

SUPPORTING GENERAL EDUCATION TEACHER’S UNDERSTANDING AND IMPLEMENTATION OF BEST PRACTICES FOR AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN THE CLASSROOM A Project Presented to the faculty of the Graduate and Professional Studies in Education California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Education (Special Education) by Karla Wright Miller SPRING 2013 SUPPORTING GENERAL EDUCATION TEACHER’S UNDERSTANDING AND IMPLEMENTATION OF BEST PRACTICES FOR AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN THE CLASSROOM A Project by Karla Wright Miller Approved by: ____________________________________________, Committee Chair Rachael A. Gonzales, Ed.D. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Karla Wright Miller I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. ___________________________________________, Department Chair Susan Heredia, Ph.D. _____________________________ Date Graduate and Professional Studies in Education iii Abstract of SUPPORTING GENERAL EDUCATION TEACHER’S UNDERSTANDING AND IMPLEMENTATION OF BEST PRACTICES FOR AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN THE CLASSROOM by Karla Wright Miller Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a group of pervasive developmental disorders that cause significant impairments in communication and social interaction. The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network -

Has Portrayal of Disabled People in the Media

BROADSHEET : MOVING IMAGE PORTRAYAL OF DISABILITY: THEN AND NOW! Has portrayal of disabled people in the media improved in recent years? There are more story lines about disabled characters with more subtlety and less stereotyping in television and film. Television-Carrie Mathieson (bi-polar)in Homeland played by Claire Danes; Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini ) keeps his mental health anxiety issues going through 7 series of the Sopranos; Monk, the detective with OCPD, brings his unique thinking to solve crimes, Doc Martin, played by Martin Clunes, with OCD has proved very popular, as the audience engage with his difficulty in navigating the world. There has been a welcome casting of disabled actors to play disabled characters in soaps, and long running dramas. This builds on the pioneering retaining of Roger Tonge as Sandy Richardson when he developed Hodgkin’s used crutches and a wheelchair in Crossroads ( ATV 1964-1981) and Julie Fernandez (wheelchair user) in Eldorado (BBC 1981-82); Adam Best in the BBC’s Eastenders (David Proud 2009-2010) followed by Donna Yates (Lisa Hammond) of short stature and wheelchair user, 2014 onwards. Kitty Mc Geever (blind) played Lizzie Lakely in Emmerdale (ITV from 2009-2013). In Hollyoaks Kelly Marie Stewart (wheelchair user) played Haley Ramsey. More recently, wheelchair using Cherylee Houston plays Izzy Anstey in Coronation Street. Liz Carr plays Clarrisa Mullery in Silent Witness. American long running series have cast more disabled actors portraying disabled parts, Paula Sage (learning difficulties) plays Roberta Brogan in Afterlife; Peter Drinklage ( restricted growth) plays Tyrone in Game of Thrones; R J Mitte (cerebral palsy) plays Walt Junior in Breaking Bad. -

Mediafishpresents

28 March - 8 April 2011 leedsyoungfilm.com MediaFishpresents 1 Welcome to the 2011 Leeds Tickets City Centre Box Office Young People’s Film Festival 0113 224 3801 presented by MediaFish! Opening Gala All Other Films A big ‘Ay up’ from MediaFish, welcome to Young person (Under 19s) £4.50 £2.50 our Film Festival! We are a group of young people Adult with young person (Over 19s) £6.00 £3.50 who love film and want to share that passion with you. Adult without young person (Over 19s) £6.00 £5.00 We don’t just organise the Film Festival, we meet every week at Leeds Film Academy to talk film, eat popcorn Buy a Golden Ticket and see and come up with ideas for cool movie stuff. all the films* from just £12.50 Check out www.leedsyoungfilm.com to find out more (*excludes Opening Gala and We ❤ Anime films). and see how you could get involved. Single Golden Ticket £12.50 (1 person, either a young person or an adult) We hope you enjoy our festival! Double Golden Ticket £20.00 The MediaFish team (2 people, either 2 young people, 2 adults or 1 of each) Family Golden Ticket £30.00 (Upto 4 people, either 2 adults & 2 young people, or 1 adult & upto 3 young people) We ❤ Anime Day Pass Saturday 2 April (Page 8) Young person (Under 19s) £8.00 Adult with young person (Over 19s) £12.00 Adult without young person (Over 19s) £16.00 The 12th Leeds Young People’s Film Festival returns to the The first 60 pass buyers will receive a FREE goodie-bag worth over £30.