An Inquiry Into Representations of Autism in Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study Guide by Marguerite O Lhara

A STUDY GUIDE BY MArguerite o ’hARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Introduction > Mary and Max is an animated feature film from the creators of the Academy Award-winning short animation Harvie Krumpet (Adam Elliot, 2003). This is Adam Elliot’s first full-length feature film. LikeHarvie , it is an animated film with claymation characters. However, unlike many animated feature films, it is minimal in its use of colour and the action does not revolve around kooky creatures with human voices and super skills. Mary and Max is about the lives of two people who become pen pals, from opposite sides of the world. Like Harvie Krumpet, Mary and Max is innocent but not naive, as it takes us on a journey that explores friendship and autism as well as taxidermy, psychiatry, alcoholism, where babies come from, obesity, kleptomania, sexual difference, trust, copulating dogs, religious difference, agoraphobia and much more. Synopsis at the Berlin Film festival in the seter, 1995) and WALL·E (Andrew Generation14+ section aimed at Stanton, 2008), will be something HIS IS A TALE of pen- teenagers where it was awarded that many students will find fasci- friendship between two the Jury Special Mention. How- nating. Tvery different people – Mary ever, this is not a film written Dinkle, a chubby, lonely eight-year- specifically for a young audience. It would be enjoyed by middle and old girl living in the suburbs of It is both fascinating and engaging senior secondary students as well Melbourne, and Max Horovitz, a in the way it tells the story of the as tertiary students studying film. -

Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: an Inquiry Into Method, Culture and Academia in the Making of Disability and Difference in Canada

Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: An inquiry into method, culture and academia in the making of disability and difference in Canada A dissertation submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada Copyright by John Edward Marris 2013 Canadian Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program January 2014 ABSTRACT Pausing Encounters with Autism and Its Unruly Representation: An inquiry into method, culture and academia in the making of disability and difference in Canada John Edward Marris This dissertation seeks to explore and understand how autism, asperger and the autistic spectrum is represented in Canadian culture. Acknowledging the role of films, television, literature and print media in the construction of autism in the consciousness of the Canadian public, this project seeks to critique representations of autism on the grounds that these representations have an ethical responsibility to autistic individuals and those who share their lives. This project raises questions about how autism is constructed in formal and popular texts; explores retrospective diagnosis and labelling in biography and fiction; questions the use of autism and Asperger’s as metaphor for contemporary technology culture; examines autistic characterization in fiction; and argues that representations of autism need to be hospitable to autistic culture and difference. In carrying out this critique this project proposes and enacts a new interdisciplinary methodology for academic disability study that brings the academic researcher in contact with the perspectives of non-academic audiences working in the same subject area, and practices this approach through an unconventional focus group collaboration. -

“I Can LEARN. I Can WORK” Campaign +

Autism-Europe N°74 / April 2021 “I can LEARN. I can WORK” campaign celebrated across the EU and beyond COVID-19 crisis: The situation of autistic people in times of the pandemic New EU Disability Strategy: building a Union without barriers for the next decade The ChildIN project: training chilminders across Europe for inclusion The IVEA project enhances the inclusion of autistic people through employment AE’s Congress 2022: + Join us in Cracow for a “Happy Journey through Life” Funded by the European Union Contents 03 Edito 04 The “I can LEARN. I can WORK” campaign celebrated across the EU and beyond 07 AE governing bodies’ meetings: More than 80 representatives meet virtually 08 New EU Disability Strategy : building a Union without barriers for the next decade Edito 10 Hector Diez, autistic student of physics 12 08 “My suffering in education almost killed my desire to investigate the universe” 12 COVID-19 crisis: The situation of autistic people in times of the pandemic 14 The ChildIN project: training chilminders across Europe for inclusion 16 The IVEA project enhances the inclusion of autistic people through employment 14 18 AE’s Congress 2022: Join us in Cracow for a “Happy Journey through Life” 19 Working, housing and leisure opportunities to promote the autonomy in France 20 Raising awareness and supporting families of autistic youth in Andorra 04 21 Providing innovative support to autistic people and their families in Cyprus 22 Members list More articles at: 16 www.autismeurope.org Collaborators Editorial Committee: Cristina Fernández, Harald Neerland, Zsuzsanna Szilvasy, Marta Roca, Stéfany Bonnot-Briey, Liga Berzina, Tomasz Michałowicz. -

Autism and Aspergers in Popular Australian Cinema Post-2000 | Ellis | Disability Studies Quarterly

Autism and Aspergers in Popular Australian Cinema Post-2000 | Ellis | Disability Studies Quarterly Autism & Aspergers In Popular Australian Cinema Post 2000 Reviewed By Katie Ellis, Murdoch University, E-Mail: [email protected] Australian Cinema is known for its tendency to feature bizarre and extraordinary characters that exist on the margins of mainstream society (O'Regan 1996, 261). While several theorists have noted the prevalence of disability within this national cinema (Ellis 2008; Duncan, Goggin & Newell 2005; Ferrier 2001), an investigation of characters that have autism is largely absent. Although characters may have displayed autistic tendencies or perpetuated misinformed media representations of this condition, it was unusual for Australian films to outright label a character as having autism until recent years. Somersault, The Black Balloon, and Mary & Max are three recent Australian films that explicitly introduce characters with autism or Asperger syndrome. Of the three, the last two depict autism with sensitivity, neither exploiting it for the purposes of the main character's development nor turning it into a spectacle of compensatory super ability. The Black Balloon, in particular, demonstrates the importance of the intentions of the filmmaker in including disability among notions of a diverse Australian community. Somersault. Red Carpet Productions. Directed By Cate Shortland 2004 Australia Using minor characters with disabilities to provide the audience with more insight into the main characters is a common narrative tool in Australian cinema (Ellis 2008, 57). Film is a visual medium that adopts visual methods of storytelling, and impairment has become a part of film language, as another variable of meaning within the shot. -

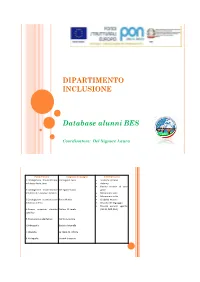

DIPARTIMENTO INCLUSIONE Database Alunni

DIPARTIMENTO INCLUSIONE Database alunni BES Coordinatore: Del Signore Laura Piano di lavoro Insegnanti di sostegno Ambiti di ricerca 1.Catalogazione strumentazione Del Signore Lucia Sindrome di Down nel plesso Paola Sarro Autismo Ritardo mentale di vario 2.Catalogazione strumentazione Del Signore Laura grado nel plesso di S.Giovanni Incarico Minorazione vista Minorazione udito 3.Catalogazione strumentazione Parisi Monica Disabilità motoria nel plesso di Pico Disturbo del linguaggio Disturbi evolutivi specifici 4.Ricerca materiale didattico Gelfusa M. Lorella (ADHD, DOP, DSA) specifico 5.Ricerca personaggi famosi Cerrito Loredana 6.Filmografia Barbera Antonella 7.Sitografia La Starza M. Vittoria 8.Bibliografia Gerardi Giovanna DIPARTIMENTO INCLUSIONE 1. Plesso “Paola Sarro” 2. Plesso di San Giovanni Incarico 3. Plesso di Pico 4. Schede didattiche alunni con disabilità 5. Filmografia sulla disabilità 6. Personaggi famosi con disabilità 7. Sitografia 8. Bibliografia 1. Plesso “Paola Sarro” RISORSE DI PLESSO “PAOLA SARRO” RISORSE STRUTTURALI Laboratorio artistico-espressivo Laboratorio di lettura Laboratorio di informatica Laboratorio musicale Palestra Laboratorio lingua inglese RISORSE MATERIALI DISPONIBILI Strumentazioni Pc Lim Materiale didattico Abaco multibase n.3 Casetta delle figure geometriche Percorso sensoriale Solidi Blocchi logici Tellurio Regoli Globo terrestre Software Erickson Dislessia e trattamento sub lessicale Produzione del testo scritto 1 e 2 Geografia facile 1 e 2 Nel mondo dei numeri e delle operazioni 2 e 3 Recupero in …abilità di scrittura 2 Giocare con le parole Un mare di numeri Decodifica sintattica della frase Risolvere i problemi per immagini Sviluppare le competenze semantico-lessicali Un mare di parole Comprensione e produzione verbale Giochi..amo con la storia Hallo Deutsch: attività per l’apprendimento del tedesco Risorse materiali richieste Abbonamenti riviste Guida didattiche 2. -

Educational Inclusion for Children with Autism in Palestine. What Opportunities Can Be Found to Develop Inclusive Educational Pr

EDUCATIONAL INCLUSION FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM IN PALESTINE. What opportunities can be found to develop inclusive educational practice and provision for children with autism in Palestine; with special reference to the developing practice in two educational settings? by ELAINE ASHBEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Education University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Amendments to names used in thesis The Amira Basma Centre is now known as Jerusalem Princess Basma Centre Friends Girls School is now known as Ramallah Friends Lower School ABSTRACT This study investigates inclusive educational understandings, provision and practice for children with autism in Palestine, using a qualitative, case study approach and a dimension of action research together with participants from two educational settings. In addition, data about the wider context was obtained through interviews, visits, observations and focus group discussions. Despite the extraordinarily difficult context, education was found to be highly valued and Palestinian educators, parents and decision–makers had achieved impressive progress. The research found that autism is an emerging field of interest with a widespread desire for better understanding. -

The Autism Spectrum Information Booklet

The Autism Spectrum Information Booklet A GUIDE FOR VICTORIAN FAMILIES Contents What is Autism? 2 How is Autism Diagnosed? 4 Acronyms and Glossary 6 Common Questions and Answers 7 What does Amaze do? 11 Funding and Service Options 12 Helpful Websites 14 National Disability Insurance Scheme 16 Suggested Reading 18 This booklet has been compiled by Amaze to provide basic information about autism from a number of perspectives. It is a starting point for people with a recent diagnosis, parents/carers of a newly diagnosed child or adult, agencies, professionals and students learning about the autism spectrum for the first time. Once you have read this information package, contact Amaze if you have any other questions or you require more information. 1 What is Autism? Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that causes substantial impairments in social interaction and communication and is characterised by restrictive and repetitive behaviours and interests. People on the autism spectrum may be affected in the following ways: Social Interaction IN CHILDREN IN CHILDREN May display indifference Does not play with other children Joins in only if adult assists & insists People on the autism spectrum may not appear to be interested in joining in with others, or they may want to join in but not know how. Their attempts to respond to social contact may appear repetitive or odd. Alternatively, they may be ‘too social’, such as showing affection to strangers. In general, people on the autism spectrum often have poor social skills and difficulty understanding unwritten social rules. They often lack understanding of acceptable social behaviour. -

11/14/13 Complete List Family & Community Resource Center

11/14/13 Complete List Family & Community Resource Center Special School District of St. Louis County 12110 Clayton Road St. Louis, MO 63131 314-989-8438/989-8108/989-8194 A+ Guide to Transitions from High School to College for Special Education. (2001/video/50 minutes) (2000/DVD) A "college prep" video for parents and students. Teachers, parents and school administrators describe the transition process and offer their best advice for having a positive experience. A is for All Aboard! Paula Kluth & Victoria Kluth (2010) Grades K and up. Fun facts, vibrant art, and in-the-know slang about trains. (32 pages) A is for Autism, F is for Friend. Joanna L. Keating-Velasco (2007) Grades 3 and up. A kid's book on making friends with a child who has autism. (54 pages) The ABA Program Companion: Organizing Quality Programs for Children with Autism and PDD. J Tyler Fovel, MA. (2002) Helps the reader integrate important theories and concepts from ABA into powerful, practical and comprehensive educational programming, from assessment through program methodology and evaluation of results. Manual & CD. The ABCs of Autism. M. Davi Kathiresan (2000) Grades K and up. This book was written to educate families, children and professionals and make them aware of the skills, strengths and capacities of persons with autism. ABCs of Emotional Behavioral Disorder. (video) (2004) (35 minutes) Outlines a best practice approach to successfully integrate elementary and middle school students with Emotional or Behavioral Disorders into the educational mainstream. ABC’s of Inclusive Child Care. (video) (1993) (14 minutes) Resource to encourage child care providers to accept children with developmental disabilities and to increase public awareness of the capabilities of individuals with disabilities. -

Reelabilities.Org

OCEAN HEAVEN MOURNING (SOOG) FILMS XIAO LU XUE | CHINA | 2010 | 96 MIN | NARRATIVE MORTEZA FARSHBAF | IRAN | 2011 | 85 MIN | NARRATIVE SPECIAL EVENTS SEVEN KEYS TO THEATER BREAKING Jet Li, in his first dramatic role, stars in this moving This cinematic road trip follows a deaf couple and their UNLOCK AUTISM THROUGH BARRIERS story of a father’s tireless love for his autistic son and young nephew on their way to Tehran. Before they get there, HEIDI LATSKY DANCE / Elaine Hall, author and founder of The (TBTB) Miracle Project, discusses her newly his attempt to teach his son the life skills necessary the couple must break the news to the boy that his parents THE GIMP PROJECT The only Off-Broadway theater published book Seven Keys to Unlock dedicated to advancing professional to surviving on his own. A poignant tribute to parents’ were killed in an accident but the journey proves to be more Pushing her physically integrated work Autism (Elaine Hall and Diane Isaacs, complex than they had expected. actors and writers with disabilities infinite love for their children. beyond conventional boundaries, Heidi Jossey-Bass Publishing, 2011). When presents a staged reading of William CINEMABILITY— OPENING NIGHT Latsky offers a preview of “Somewhere.” traditional therapies failed to help her Shakespeare’s The Merchant Of Venice. SPECIAL PRESENTATION Wildly different renditions of “Over Keke, India, Rick Guidotti/Positive Exposure autistic son, Hall sought out creative TBTB has been hailed by The NY Times Feb 9, 7 pm at The JCC in Manhattan the Rainbow,” a song so easily people—actors, writers, and teachers— Ben Affleck, Jamie Foxx, William as “an extraordinary troupe designed Followed by reception (PRINSESSA) misconstrued in the context of POSITIVE EXPOSURE to work with him. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

Product Guide

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE AFM AT YOUR FINGERTIPS – THE PDA CULTURE IS HAPPENING! THE FUTURE US NOW SOURCE - SELECT - DOWNLOAD©ONLY WHAT YOU NEED! WHEN YOU NEED IT! GET IT! SEND IT! FILE IT!© DO YOUR PART TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING In 1983 The Business of Film innovated the concept of The PRODUCT GUIDE. • In 1990 we innovated and introduced 10 days before the major2010 markets the Pre-Market PRODUCT GUIDE that synced to the first generation of PDA’s - Information On The Go. • 2010: The Internet has rapidly changed the way the film business is conducted worldwide. BUYERS are buying for multiple platforms and need an ever wider selection of Product. R-W-C-B to be launched at AFM 2010 is created and designed specifically for BUYERS & ACQUISITION Executives to Source that needed Product. • The AFM 2010 PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is published below by regions Europe – North America - Rest Of The World, (alphabetically by company). • The Unabridged Comprehensive PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH contains over 3000 titles from 190 countries available to download to your PDA/iPhone/iPad@ http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/Europe.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/NorthAmerica.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/RestWorld.doc The Business of Film Daily OnLine Editions AFM. To better access filmed entertainment product@AFM. This PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is divided into three territories: Europe- North Amerca and the Rest of the World Territory:EUROPEDiaries”), Ruta Gedmintas, Oliver -

Somewhere in the Middle: Understandings of Friendship and Approaches to Social Engagement Among Postsecondary Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Somewhere in the Middle: Understandings of Friendship and Approaches to Social Engagement Among Postsecondary Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder by Jason Manett A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Jason Manett 2020 Somewhere in the Middle: Understandings of Friendship and Approaches to Social Engagement Among Postsecondary Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder Jason Manett Doctor of Philosophy Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2020 Abstract This study examined the social experiences and understandings of friendship of postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Ten students from Ontario postsecondary institutions participated in semi-structured interviews and data were analyzed according to the principles of modified grounded theory. Participants’ responses indicate that they had conventional understandings of friendship that included compatible interests and aspects of intimacy. They expressed confidence about their strengths, personalities, and social abilities, and were motivated to develop and maintain friendships and participate in social activities with their peers. They also described experiencing communication challenges and difficulty engaging in various social environments. Participants positioned themselves as “somewhere in the middle” of peers with and without ASD in terms of social functioning, viewed supports as appropriate for others with ASD but not themselves, and employed strategic approaches to socializing in order to balance their desire for social connection with the impacts of the challenges that they experienced. They described areas ii of satisfaction and dissatisfaction or ambivalence with regard to their social lives.