Current Jewish Questions Boxing / Mixed Martial Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leviathan Jewish Journal Is an Open Medium Through Which Jewish Students and Their Allies May Freely Express Their Opinions

Spring 2012 Vol. 39-3 LeviathanJewish Journal Jewish Journal Statement of Intent Leviathan Jewish Journal is an open medium through which Jewish students and their allies may freely express their opinions. We are commited to responsibly representing the views of each individual author. Every quarter we aim to publish a full and balanced spectrum of media exploring Jewish identity and social issues. The opinions presented in this journal do not always represent the collective opinion of Leviathan’s staff, the organized Jewish community, or the University of California. Editor-in-Chief Art Director Aaron Giannini Karin Gold Production Manager Publisher Karin Gold Shani Chabansky Managing Editor Faculty Sponsor Savyonne Steindler Bruce Thompson Business Manager Contributors Karina Garcia Hanna Broad Shelby Backman Web Manager Sophia Smith Oren Gotesman Andrew Dunnigan Gabi Kirk Additonal Staff Members Anisha Mauze David Lee Amrit Sidhu Ephraim Margolin Allison Carlisle Jennine Grasso Matthew Davis Cover Art Karin Gold Letter From the Editor After a hectic and controversial year, the Leviathan Staff thought it would be beneficial to revisit the subject of what it means to be Jewish in today’s world. This is in no way a simple question, as the diversity of the Jewish people speaks to the fluid- ity of our identity. Are we the culmination of our history, inheriting monotheism through our holy lineage? Or are we just fingerprints, products of our ever-changing environment, blips on the cosmic stage? Are we grounded in our past, or is it our obligation to live in the present and look towards the future? We did not decide on our cover image this quarter without much deliberation. -

New York State Boxing Hall of Fame Announces Class of 2018

New York State Boxing Hall of Fame Announces Class of 2018 NEW YORK (January 10, 2018) – The New York State Boxing Hall of Fame (NYSBHOF) has announced its 23-member Class of 2018. The seventh annual NYSBHOF induction dinner will be held Sunday afternoon (12:30-5:30 p.m. ET), April 29, at Russo’s On The Bay in Howard Beach, New York. “This day is for all these inductees who worked so hard for our enjoyment,” NYSBHOF president Bob Duffy said, “and for what they did for New York State boxing.” Living boxers heading into the NYSBHOF include (Spring Valley) IBF Cruiserweight World Champion Al “Ice” Cole (35-16-3, 16 KOs), (Long Island) WBA light heavyweight Lou “Honey Boy” Del Valle (36-6-2, 22 KOs), (Central Islip) IBF Junior Welterweight World Champion Jake Rodriguez (28-8-2, 8 KOs), (Brooklyn) world lightweight title challenger Terrence Alli (52-15-2, 21 KOs), and (Buffalo) undefeated world-class heavyweight “Baby” Joe Mesi (36-0, 29 KOs). Posthumous participants being inducted are NBA & NYSAC World Featherweight Champion (Manhattan) Kid “Cuban Bon Bon” Chocolate (136-10-6, 51 KOs), (New York City) 20th century heavyweight James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett (11-4-3, 5 KOs), (Williamsburg) World Lightweight Champion Jack “The Napoleon of The Prize Ring” McAuliffe, (Kingston) WBC Super Lightweight Champion Billy Costello (40-2, 23 KOs), (Beacon) NYSAC Light Heavyweight World Champion Melio Bettina (83-14-3, 36 KOs), (Brooklyn/Yonkers) world-class middleweight Ralph “Tiger” Jones (52-32-5, 13 KOs) and (Port Washington) heavyweight contender Charley “The Bayonne Bomber” Norkus (33-19, 19 KOs). -

Russian-Speaking Jews 25 Years Later

1989-2014: Russian-Speaking Jews 13 25 Years Later On November 9, 1989 the Berlin Wall fell. !e faced with the practical realities of realizing what event came as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's had hitherto been only a distant hope. Amid the policies of glasnost and perestroika had steadily headiness of a miraculous time, each began the led to a loosening of Moscow's rigid control over hard work of developing concrete responses to a its subject peoples. Yet the breaching of this stark challenge of unanticipated proportions. symbol of the communist East's self-enforced From 1989 and throughout the following 25 years, isolation was a climactic sign that change of world Jewry invested massively in meeting the historic proportions was taking place. two main elements of this challenge: facilitating !e change took the world, and Jews everywhere, the emigration of almost two million people and by surprise. A great superpower and an implacable their resettlement, preferably in Israel and, if not, foe was dying. It was not defeated on the battlefield elsewhere; and responding to the needs – cultural, of a cataclysmic war. Rather, like Macarthur's spiritual, material – and aspirations of the Jews who, old soldiers, it just faded away, its ebbing decline out of choice or necessity, remained in the region. barely perceptible until suddenly it was plain to all. Of the estimated 2-3 million Jews and their For the Jewish world, the change was monumental. relatives who lived in the Soviet Union in 1989, the After decades of separation from the rest of the overwhelming majority emigrated, leaving only Jewish people, after Western Jewries' years of several hundred thousand in the region today. -

And Still Karabus Isn't Free

friday 5 april 2013 / 25 nissan 5773 volume 17 – number 11 Zaidel- south african Rudolph brings Africa to Israel (page 10) Jewish Report www.sajewishreport.co.za Photo courtesy www.capebod.org.za And still Karabus isn’t free On February 11 a large protest was held outside the Cape Town International Convention Centre, where an Emirati medical delegation was attending the World Congress of Paediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, in the name of freeing Prof Cyril Karabus. Protestors came from across the spectrum of the SA community, but still Karabus has not yet been freed. See story on page 3. Wits promises strong DAVIS: Distance lends ANC stance on Israel Standard Bank, Plits action against Reshef perspective to Jewish shouldn’t impact reaffirm commitment ADVERTISING protesters view business: Jon Medved to Joburg inner city SUPPLEMENT: The university’s focus pertains to The SA community, smaller than The reason for Israeli success “We are seeing a lot of de- Keeping the violation of rights of the mu- ever and gutted by emigration, started with culture, not just mand for affordably-priced sician, concertgoers, patrons and does not reflect the growing di- brains. It began with risk. Jews accommodation. We wanted proudly guests, as well as on honouring versity in the Jewish world and had always lived with risk to provide units which not kosher in the rights of individuals rather the possibility of returning to throughout their history. Israel only meet this requirement, than the country of origin or days of old when Judaism stood has faced greater risks than but will provide tenants with South Africa ethnicity of anybody concerned. -

America's Russian-Speaking Jews Come of Age

Toward a Comprehensive Policy Planning for R u s s i a n - Speaking Jews in North America Project Head Jonathan D. Sarna Contributors Dov Maimon, Shmuel Rosner In dealing with Russian-speaking Jews in North America, we face two main challenges and three possible outcomes. CHALLENGES: 1. Consequences of disintegration of the close-knit immigrant society of newly arrived Russian-speaking Jews. 2. Utilizing the special strengths of Russian-speaking Jews for the benefit of the wider American Jewish community. POSSIBLE OUTCOMES: 1. The loss of Jewish identity and rapid assimilation. 2. An adaptation of American-Jewish identity (with the benefits and shortcomings associated with it). 3. A formation of a distinctive Russian-speaking Jewish identity strong enough to be further sustained. There is a 10 to 15-year window of opportunity for intervention with this population. There is also a need to integrate, in a comprehensive manner, organizations to positively intervene in the field. At this preliminary stage, several recommendations stand out as urgent to address this population’s needs: - An effort on a national scale to assist the communities that are home to the majority of Russian-speaking Jews. - Funding for programs that will encourage Russian-speaking Jews to move into Jewish areas. - Special programs to promote in-marriage. - Dialogue mechanisms for Russian-speaking Jews in Israel, the US, Germany, and the Former Soviet Union. - Programs building on Russian-speaking Jews’ sense of peoplehood to bolster ties among all Jews to Israel. - Possible reciprocity between Jewish education and education in science and math for Russian-speaking Jews ("Judaism for math"). -

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 13, 1929

rnmmmmtimiiifflmwm tMwwwiipiipwi!^^ 32 BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, NEW YORK, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13, 1929. Iowa Has Punished ows More Than Disciplining The Double-Fused Bomb—Which'li Explode It? By Ed Hughes Few Athletes Needed .0., Ere House Is Cleaned Despite Ruby's Punch -t • By GEORGE CVRRIE By ED HUGHES. io'.va( having cleaned house by simply taking a broom A double-fused knockout bomb, figuratively speaking, and sweeping her outstanding athletes out oi the locker will splutter and probably explode in the Garden ring tonight, room, cannot be accused of dodging the issue for which she Jimmy McLarnin, the Irish Thumper, and Ruby Goldstein, was suspended by the "Big Ten" when she insists upon much-thumped idol of the Ghetto, will meet* naming her own athletic director^ Not only has she dis- in a scheduled ten-rounder. The betting is TO$f__, Sbrl.and 7—5 on McLarnin, but the talk you year's basketball team apart, ail to prove the simon purity might jsay is almost at evens. McLarnin of her intentions. and Goldstein are two of the hardest hitting The Hawkeyes are thus in a position to demand rein welterweights that have appeared since the statement and, reinstated, to demand a follow up of the dangerous days of Joe Walcott, famed Bar- Carnegie Foundation report so lar<s>— badoes demon. as it concerns sister universities in) boys—ah, my friends, countrymen the "Big Ten" conference. Incidentally, destiny, with a sense of and New Yorkers, that is another the dramatic, decreed that the great col-, A fair indication of the drastic story! mopping up which Iowa has under One awaits the action of Iowa ored gladiator of other days should be a taken may t>e gathered from the with a hopeful but not expectant part of tonight's turnup. -

Tough Jews: Fathers, Sons, and Gangster Dreams Why Should You Care?

Jewish Tough Guys Gangsters and Boxers From the 1880s to the 1980s Jews Are Smart When we picture a Jew the image that comes to mind for many people is a scientist like Albert Einstein Jews Are Successful Some people might picture Jacob Schiff, one of the wealthiest and most influential men in American history Shtarkers and Farbrekhers We should also remember that there were also Jews like Max Baer, the heavyweight Champion of the World in 1934 who killed a man in the ring, and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro, who “helped” settle labor disputes. Why Have They Been Forgotten? “The Jewish gangster has been forgotten because no one wants to remember him , because my grandmother won’t talk about him, because he is something to be ashamed of.” - Richard Cohen, Tough Jews: Fathers, Sons, and Gangster Dreams Why Should You Care? • Because this is part of OUR history. • Because it speaks to the immigrant experience, an experience that links us to many peoples across many times. • Because it is relevant today to understand the relationship of crime and combat to poverty and ostracism. Anti-Semitism In America • Beginning with Peter Stuyvesant in 1654, Jews were seen as "deceitful", "very repugnant", and "hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ". • In 1862, Ulysses S. Grant issues General Order 11, expelling all Jews from Tennessee, Mississippi and Kentucky. (Rescinded.) • In 1915, Leo Frank is lynched in Marietta, Georgia. • 1921 and 1924 quota laws are passed aimed at restricting the number of Jews entering America. • Jews were not the only target of these laws. -

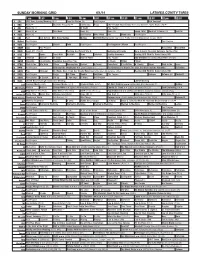

Sunday Morning Grid 6/1/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/1/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Press 2014 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Exped. Wild World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: FedEx 400 Benefiting Autism Speaks. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program The Forgotten Children Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Heart 411 (TVG) Å Painting the Wyland Way 2: Gathering of Friends Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions For You (TVG) 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) El Chavo Fútbol Fútbol 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Walk in the Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

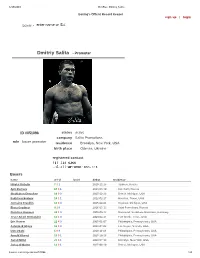

Dmitriy Salita

6/18/2019 BoxRec: Dmitriy Salita Boxing's Official Record Keeper sign up | login enter name or ID# boxer ▾ Dmitriy Salita - Promoter ID #051096 status active company Salita Promotions role boxer promoter residence Brooklyn, New York, USA birth place Odessa, Ukraine registered contact Boxers name w-l-d last 6 debut residence Nikolai Buzolin 7 3 1 2010-12-15 Tyumen, Russia Apti Davtaev 17 0 1 2013-03-30 Kurchaloi, Russia Shohjahon Ergashev 16 0 0 2015-12-23 Detroit, Michigan, USA Bakhtiyar Eyubov 14 1 1 2012-02-17 Houston, Texas, USA Jermaine Franklin 18 0 0 2015-04-04 Saginaw, Michigan, USA Elena Gradinar 9 1 0 2016-05-13 Saint Petersburg, Russia Christina Hammer 24 1 0 2009-09-12 Dortmund, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany Jesse Angel Hernandez 12 3 0 2009-02-14 Fort Worth, Texas, USA Eric Hunter 21 4 0 2005-01-07 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Aslambek Idigov 16 0 0 2013-07-02 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Izim Izbaki 1 0 0 2018-11-16 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Arnold Khegai 15 0 1 2015-10-28 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Jarrell Miller 23 0 1 2009-07-18 Brooklyn, New York, USA Jarico O'Quinn 12 0 1 2015-04-10 Detroit, Michigan, USA boxrec.com/en/promoter/51096 1/4 6/18/2019 BoxRec: Dmitriy Salita name w-l-d last 6 debut residence Samuel Peter 38 7 0 2001-02-06 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Nikolai Potapov 20 1 1 2010-03-13 Brooklyn, New York, USA Umar Salamov 24 1 0 2012-12-15 Henderson, Nevada, USA Elena Saveleva 5 1 0 2017-06-23 Pushkino, Russia Claressa Shields 9 0 0 2016-11-19 Flint, Michigan, USA Vladimir Shishkin 8 0 0 2016-07-31 Serpukhov, -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

Canadian National Cost. Vacations

'. ( . -_ ... ' ., .~"::-", . \',' , PAGE 13 PAGE 12 THE J·EWISH POST THE JEWISH POST r ture;, and jet black eyes, his expres it· will soon be broken, Anyway, r Florence Brown, Mrs. iii. Brown, Miss lllunity of this city with the opportun mes N. Pros·terman, H. iii. Schmer sion never changes. At first glance Max, who hails from the south-west, Hannah Lipetz, lliiss Sada Simon, ity of seeing this famous play, so· ex and Z. Natanson. Assisting the hostess were Mrs. A. you wouldn't think that he could saw more J-ews than he ev€-'l' did in his Vegreville . News Miss Mary Waterman and Miss E. cellently rendered, in Jewisli. Sport Notes .life whil" he sat on th" bench in Mr. R. iii. Bernstein creditably per .AJbrams, H.' Hy'mnn, }1. Pamovitch smash a derby hat. He looks like a _________________________By Hannah lliiller 1 Wat",·man. college freshman who is very much Brooklyn. l • • • formed the' role of "King Lenr," whUe and S. Sandomirsky. impressed with his new alma mater. * * * The Young Judaea of Vegreville, iiiI'. and Mrs. Marantz ~ntertained Mrs. M. Bernstein took the part of • • • By George Joel . Andy Cohen ill Again, Out Again .. Bruce Flowers took one look at him Alta., was recently r"'organized and at an informal haute dance on Satur leading lady as "Taibele." Other A Silver Tea under. the auspices of I and didn't Im()w whcthm' to :Eight him W'hile Reese was doctoring his S01'e gave a tea and court whist par.ty at day evening, in honor of their son, characters wer-e: 1\11f. -

Ultimate Champion Biographies

Ultimate Champion Biographies Stephan "American Psycho" Bonnar Rich Styles In the summer of 2004 Stephan was chosen to be a cast member of Rich was the President of Production for D.S.I. Productions and he Spike TV's "The Ultimate Fighter." He went on to fight in the finale was the Head of Film Production and Development for Sunset Films against Forrest Griffin, a fight which many describe as the greatest International. Rich has been involved in the production of 10 in UFC history and one of the most important moments in MMA, movies in various capacities, including writing, directing and propelling it to stratospheric heights. producing. His most recent work is Ultimate Champion which he co‐produced with Ted Fox. Rich’s next two projects include The Daniel Bernhardt Unknown, and Hybrid. Daniel has appeared in a number of martial arts films including Bloodsport 2, 3, and 4 (in which he replaced actor and martial artist Sean "Muscle Shark" Sherk Jean‐Claude Van Damme), and had a supporting role in the box Japanese fans gave him the nickname “Muscle Shark.” In October office hit The Matrix Reloaded, the second of The Matrix trilogy, as of 2006 he defeated Kenny “Kenflo” Florian to become the UFC Agent Johnson. Lightweight World Champion. Leila Arcieri Gilbert "El Niño" Melendez Arcieri was crowned “Miss San Francisco” in the 1997 Miss Gilbert defeated Clay Guida in 2006 for the Strikeforce Crown and California Pageant and was later a spokesmodel for Coors Lite Beer. he has appeared on several best “pound for pound” fighters lists.