Debunking Dark Emu: Did the Publishing Phenomenon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Dark Emu ‘Hoax’: Takedown Reveals the Emperor Has No Clothes

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Dark Emu ‘hoax’: takedown reveals the emperor has no clothes Author Bruce Pascoe. • Victoria Grieve-Williams • July 2, 2021 There is much terrible irony in Dark Emu’s struggle to shoehorn classical Aboriginal Australia into the supposedly advanced world of agriculture.” - Peter Sutton Can the Dark Emu scandal be explained by the fact that Australians seem inordinately susceptible to a good old-fashioned literary hoax? From the infamous Ern Malley affair through to Norma Khouri and Helen Demidenko, we seem to have an appetite for being misled. There are examples in the Aboriginal world, too. Ian Carmen, a white taxidriver from Adelaide, posed as a Pitjantjatjara survivor of the Stolen Generation, Wanda Koolmatrie, to write an “autobiography” called My Own Sweet Time. This book was used as a text for the NSW Higher Schools certificate curriculum. In 2014, Bruce Pascoe, exhibiting zeal and showmanship, produced a book that has now sold more than 260,000 copies. Surprise, it says that we Indigenous Australians are more like white people, and therefore, somehow, more sophisticated than “mere” hunter-gatherers. Well thanks, but no thanks. Pascoe’s thesis went entirely against my lived experience, learning as a child to the “summer” and “winter” camps of my mother’s people. They moved to the Barrington 2 Mountains, even in snow, for fatter game and thicker furs, and returned to the coast for the mullet runs in spring, feasting and meeting with other groups. The bunya bunya from the giant cones in the bunya tree, and the huge mulloway my grandfather caught, kept the family alive during the Depression. -

Control and Conservation of Abundant Kangaroo Species

animals Review The Perils of Being Populous: Control and Conservation of Abundant Kangaroo Species David Benjamin Croft 1,* and Ingrid Witte 2 1 School of Biological Earth & Environmental Sciences, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia 2 Rooseach@RootourismTM, Adelaide River, NT 0846, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Kangaroos likely prospered for most of the last 65,000 years under the landscape management of Australia’s first people. From the arrival of British colonists in 1788, European agricultural practices, crops and livestock transformed the landscape to one less favourable to indigenous flora and fauna. However, the six species of large kangaroos persisted and came into conflict with cropping and pastoral enterprises, leading to controls on their abundance. After mass killing for bounties, a commercial industry emerged in the 1970s to sell meat and hides into domestic and international markets. The further intention was to constrain kangaroo abundance while sustaining kangaroos in the landscape. Human–human conflict has emerged about the necessity and means of this lethal control. Further control of the abundance of four of the six species is promoted. Their abundance is considered by some as a threat to biodiversity in conservation reserves, removing these as a haven. We therefore propose returning the kangaroos’ stewardship to the current and future generations of Aboriginal Australians. We envisage that a marriage of localised consumptive (bush tucker) and non-consumptive (wildlife tourism) uses in the indigenous-protected-area estate can better sustain abundant kangaroo populations into the future. Citation: Croft, D.B.; Witte, I. The Abstract: Australia’s first people managed landscapes for kangaroo species as important elements Perils of Being Populous: Control and of their diet, accoutrements and ceremony. -

Dark-Emu Studyguide.Pdf

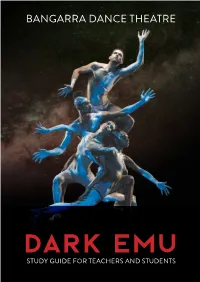

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated September 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this Study Guide contains names and images of, and quotes from, deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Bangarra ensemble, photo by Daniel Boud Back Cover: Yolanda Lowatta, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Inspired by Bruce Pascoe’s award-winning book of the same name, Dark Emu explores the vital life force 03 of flora and fauna in a series of dance stories. Directed Introduction by Stephen Page, Dark Emu is a dramatic and evocative dance response to the assault on land, people and spirit. We celebrate this sharing of knowledge, the heritage 04 of careful custodianship, and the beauty that Bruce Using this Study Guide Pascoe’s vision urges us to leave to the children. -

Dark Emu Exposed

and working holidays) and the Cruise Industry, which gives look beyond what we ourselves were taught in school details on the economic benefits that cruising brings to and what is portrayed in mainstream media. He uses the Australian economy. Excellent data and trends can evidence from a range of sources, including early colonists be seen in the link to the Trip Advisor Travel Barometer and explorers, to put forward a very logical and well- Reviews for 2016 which takes a global view of current trends and documented argument that Aboriginal Australians were even breaks down the data to highlight the generational not hunter-gatherers. differences in decision making, amenities preferred and There are definitely applications for Dark Emu in reasons for travel. the classroom. It links to a number of geographic This resource could also be used for Year 9 Unit 2: concepts including place, environment, sustainability, Geography of Interconnections, where the link to Australia. interconnection and change. The language use is com allows students to plan their own holiday around accessible enough for middle and senior high school Australia, with further links to weather, places to go, sites students (with some scaffolding) and extracts could to see, accommodation, time zones and the like. Data very easily be provided to students. For example, Year can easily be extracted and used to teach graphing and 10 students could compare current land management mapping skills. strategies in Australia to the Aboriginal approaches. Year 9 students studying food security could come up with The section on Aboriginal Tourism provides some solutions based on traditional Aboriginal agriculture. -

Suggested Reading for Cultural Information

Recommended reading Books and research focused on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, histories and cultures Reports and documents The State of Reconciliation in Australia report (2016) Reconciliation Australia The first of its kind since 2000, the State of Reconciliation in Australia report highlights what has been achieved under the five dimensions of reconciliation: race relations, equality and equity, institutional integrity, unity, and historical acceptance and makes recommendations on how we can progress reconciliation into the next generation. How to access: The State of Reconciliation in Australia is available in full or summary here. Recommended audiences: Individuals and friends Community groups Businesses and organisations Schools and early learning services (professional learning and secondary students) The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2009) United Nations, illustrated by Michel Streich On 13 September, 2007 the General Assembly of the United Nations, with an overwhelming majority of votes, adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration was over 22 years in the making. Its purpose, as described by the UN, is to set an important standard for the treatment of Indigenous peoples and to act as a significant tool in eliminating human rights violations against the planet’s over 350 million Indigenous people, while assisting them in combating discrimination and marginalisation. Only four countries voted against it: the US, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. In 2009, the Australian government decided to endorse this landmark Declaration. Michel Streich’s simple yet moving illustrations add power to The Declaration—a clear and strong statement of hope, belief and purpose and one of the most important documents of our time. -

Young Dark Emu Unit Plan – 8 Weeks

Young Dark Emu Unit Plan – 8 weeks As a result of engaging in this unit, students will understand that They can break down Indigenous racial stereotypes and contribute to reconciliation in Australia by examining, interpreting, analysing and evaluating various Indigenous texts, including The Young Dark Emu. Know – The truth about Australia’s Indigenous history and its contribution to racism against Indigenous Australians. How Indigenous people lived by examining, interpreting, analysing and evaluating the bias, choice of language, vocabulary and images in various Indigenous texts, including The Young Dark Emu. Be able to - Examine, Interpret, analyse and evaluate bias, choice of language, vocabulary and images in the Indigenous texts, including The Young Dark Emu to break down Indigenous stereotypes and contribute to reconciliation. Essential Question: How do texts written by Indigenous peoples like the Young Dark Emu breakdown Indigenous Stereotypes and contribute to reconciliation? Week Topic Video and Resources 9 Lesson 1 Lesson 2 Introduction to Stereotypes Stereotype activity and worksheet What do we know questions and group activity? 10 Lesson 1 Lesson 2 Gender Stereotypes The invisible discriminator video Stereotypes worksheet and teachers notes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FUdrd0Mg _4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3Aw eo-74kY What did you notice? Groups and then share. Why do we think this? This reveals what young students think Where did this come from? about what gender does which jobs. Did this surprise you? What happens if we flip this on its head? What is a stereotype? BBQ Area - Start by getting students to draw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tacxxzq8vN firefighter, fighter pilot, surgeon. -

Historiographical Review the Deep Past of Pre-Colonial Australia*

The Historical Journal, page of © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX HISTORIOGRAPHICAL REVIEW THE DEEP PAST OF PRE-COLONIAL AUSTRALIA* ABSTRACT. Human occupation of Australia dates back to at least , years. Aboriginal ontologies incorporate deep memories of this past, at times accompanied by a conviction that Aboriginal people have always been there. This poses a problem for historians and archaeologists: how to construct meaningful histories that extend across such a long duration of space and time. While earlier generations of scholars interpreted pre-colonial Aboriginal history as static and unchan- ging, marked by isolation and cultural conservatism, recent historical scholarship presents Australia’s deep past as dynamic and often at the cutting-edge of human technological innovation. This historiographical shift places Aboriginal people at the centre of pre-colonial history by incorpor- ating Aboriginal oral histories and material culture, as well as ethnographic and anthropological accounts. This review considers some of the debates within this expansive and expanding field, focus- ing in particular on questions relating to Aboriginal agriculture and land management and connec- tions between Aboriginal communities and their Southeast Asian neighbours. At the same time, the study of Australia’s deep past has become a venue for confronting colonial legacies, while also providing a new disciplinary approach to the question of reconciliation and the future of Aboriginal sovereignty in Australia. -

Food: Different by Design a First Nations Perspective of Food and Agriculture

Food: Different By Design A First Nations Perspective of Food and Agriculture 2021 National Science Week Teachers’ Resource: Lesson Content Directory for Cross-Curriculum Priority Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures Acknowledgements This online curriculum-linked resource was produced by the Australian Science Teachers Association (ASTA). With the exception of material that has been quoted from other sources and is identified by the use of quotation marks (“ “), or other material explicitly identified as being exempt, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The following statement must be used on any copy or adaptation of the material. Copyright: Australian Science Teachers Association 2021, except where indicated otherwise. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. The resources and links in this document have been compiled by the Australian Science Teachers Association. Design by the Australian Science Teachers Association. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this educational resource are factually correct, ASTA does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this educational resource. All links to websites were valid in June 2021. As content on the websites used in this resource book might be updated or moved, hyperlinks may cease to function. (i) Using this Resource The following resource contains a selection of available materials that teachers may find useful when addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures during National Science Week, as a part of the Cross-Curriculum Priority. -

Andrew Bolt: Leftists Finally Waking up to Bruce Pascoe's Fraud

Read Today's Paper Tributes 12:29am Wednesday, July 14th, 2021 Rewards Melbourne Today 8 °/ 15 ° Hi, Josephine News Opinion Andrew Bolt Andrew Bolt: Leftists finally waking up to Bruce Pascoe’s fraud “Aboriginal historian” Bruce Pascoe’s jig is up, with woke Leists now admitting he told untruths. Andrew Bolt Follow 3 min read June 13, 2021 - 4:13PM 201 comments Advertisement My Local Victoria National World Opinion Business Entertainment Lifestyle Sport News Sky News host Andrew Bolt says “amazing new developments” have come to light in relation to “scandal” around historian Bruce Pascoe. So called “Aboriginal historian” Bruce Pascoe pulled off the biggest hoax in Australia’s literary history. But now the jig is up, as even the woke Sydney Morning Herald and Age admit Pascoe told untruths. The news on Saturday came like a thunderclap. Until now, these two Left-wing newspapers – along with the ABC – had protected the snowy-bearded 73-year-old sage. Just last Australia Day, the SMH had this supposedly “Yuin, Bunurong and Tasmanian man” write an article about our white sins. But at the weekend the SMH and Age reported that impeccably credentialed Leftist academics – anthropologist Peter Sutton and archaeologist Keryn Walshe – had a new book detailing how Pascoe had cheated in writing his bestseller Dark Emu. Dark Emu became our hottest history book in decades by sensationally claiming Aborigines were not hunter- gatherers but “farmers” living in “houses” with “pens” in “towns” of “1000 people”. But in Saturday’s magazine cover story, Sutton and Walshe gave example after example of how Dark Emu was “riddled with errors of fact, selective quotations, selective use of evidence, and exaggeration of weak evidence”, all to make false claims that appeal to Australians who wanted to believe Aborigines weren’t “mere” hunter-gatherers. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr Michael Davis Education

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr Michael Davis Education PhD, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, 2010. Thesis title: Producing a Critique: Writing about Indigenous Knowledge, Intellectual Property and Cultural Heritage. B.A. Hons, Department of History, La Trobe University, Melbourne 1985 Current Affiliations Honorary Research Fellow, Department of History, University of Sydney 2014-15 Redmond Barry Fellow, State Library of Victoria and Melbourne University Works in Progress In Preparation Adamson, Joni, Davis, Michael, and Huang, Hsinya (eds), Oceans, Islands, Country: Humanities for the Environment in Australia, Asia-Pacific and North America, proposal in preparation to submit to Routledge Earthscan, Environmental Humanities Series, General Editors Iain McCalman and Libby Robin. Davis, M. Entangled Knowledges: Aboriginal and European Encounters on Australia’s Pacific Coast, 1770 to 1850, proposal in preparation to Palgrave MacMillan. Published Works Co-authored Holcombe, S and Davis, M (eds). 2010 Australian Aboriginal Studies. Journal of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Number 2, Special Edition: Contemporary Ethical Issues in Australian Indigenous Research. Davis, M., and Holcombe 2010.‘Whose ethics?’: Codifying and enacting ethics in research settings’, Australian Aboriginal Studies, Journal of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Number 2, Special Edition: Contemporary Ethical Issues in Australian Indigenous Research, eds Sarah Holcombe and Michael Davis: 1-9. Craig, D., and Davis, M. 2006. Ethical Relationships for Biodiversity Research and Benefit-sharing with Indigenous Peoples. Macquarie Journal of International and Comparative Environmental Law, 2(2): 31-74. Sole authored Books 1 Davis, M. 2007. Writing Heritage: The Depiction of Indigenous Heritage by European-Australians. -

Dark Emu and the Radical Difference of Pre-1788 Aboriginal Society White Australia Needs to Understand the Sheer Otherness of the Pre-1788 World

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Welcome to the fish trap: Dark Emu and the radical difference of pre-1788 Aboriginal society White Australia needs to understand the sheer otherness of the pre-1788 world. The debate hasn't got it yet. Bruce Pascoe Guy Rundle JUL 12, 2021 The principle of Indigenous fish traps, as I understand it, is to convince the fish that it is going in the opposite direction to the one it’s actually taking, and then start it turning in ever smaller circles. With the debate around Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, we now know how the fish feels. In thirty-plus years of culture wars one has never seen a stoush which is so defined by confusion, misprision, projection and people standing for the opposite of what they think they’re doing. To not know the basics of the Dark Emu wars you’d have to have been out in the desert somewhere — OK, bad metaphor, but the basics are this: in 2014, novelist and short story writer Bruce Pascoe published said book, which argued that the Aboriginal Australians, far from being wholly nomadic hunter-gatherer-foragers, had been agriculturalists and semi-sedentists, storing and farming food, and living in villages of stone huts. Their arrival on the continent was not 60,000 years ago but 120,000. 2 These cultural practices were “achievements”, Pascoe argued, which should be celebrated. The picture of hunter-gatherers moving across the surface of the earth finding food by chance and putting up shelters that were temporary at best was quite wrong. Pascoe drew in part on earlier sources, but his skills as a writer of compressed narrative gave Dark Emu a pace and energy earlier accounts lacked.