Law and Policy of Targeted Killing, 1 HARV. NAT'l SEC. J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The SRAO Story by Sue Behrens

The SRAO Story By Sue Behrens 1986 Dissemination of this work is made possible by the American Red Cross Overseas Association April 2015 For Hannah, Virginia and Lucinda CONTENTS Foreword iii Acknowledgements vi Contributors vii Abbreviations viii Prologue Page One PART ONE KOREA: 1953 - 1954 Page 1 1955 - 1960 33 1961 - 1967 60 1968 - 1973 78 PART TWO EUROPE: 1954 - 1960 98 1961 - 1967 132 PART THREE VIETNAM: 1965 - 1968 155 1969 - 1972 197 Map of South Vietnam List of SRAO Supervisors List of Helpmate Chapters Behrens iii FOREWORD In May of 1981 a group of women gathered in Washington D.C. for a "Grand Reunion". They came together to do what people do at reunions - to renew old friendships, to reminisce, to laugh, to look at old photos of them selves when they were younger, to sing "inside" songs, to get dressed up for a reception and to have a banquet with a speaker. In this case, the speaker was General William Westmoreland, and before the banquet, in the afternoon, the group had gone to Arlington National Cemetery to place a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. They represented 1,600 women who had served (some in the 50's, some in the 60's and some in the 70's) in an American Red Cross program which provided recreation for U.S. servicemen on duty in Europe, Korea and Vietnam. It was named Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO). In Europe it was known as the Red Cross center program. In Korea and Vietnam it was Red Cross clubmobile service. -

Capital Punishment of Children in Ohio: "They'd Never Send a Boy of Seventeen to the Chair in Ohio, Would They?" Victor L

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 Capital Punishment of Children in Ohio: "They'd Never Send a Boy of Seventeen to the Chair in Ohio, Would They?" Victor L. Streib Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Streib, Victor L. (1985) "Capital Punishment of Children in Ohio: "They'd Never Send a Boy of Seventeen to the Chair in Ohio, Would They?"," Akron Law Review: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol18/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CAPITAL PUNISHMENTStreib: Capital OF Punishment CHILDREN IN OHIO: "THEY'D NEVER SEND A BOY OF SEVENTEEN TO THE CHAIR IN OHIO, WOULD THEY?"* by VICTOR L. STREIB* I. INTRODUCTION After a century of imposing capital punishment for crimes committed while under age eighteen, Ohio has joined an enlightened minority of American jurisdictions in prohibiting -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Still Demanding Respect. Police Abuses Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual And

Stonewalled – still demanding respect Police abuses against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the USA Amnesty International Publications - 1 - Amnesty International (AI) is an independent worldwide movement of people who campaign for internationally recognized human rights to be respected and protected. It has more than 1.8 million members and supporters in over 150 countries and territories. Stonewalled – still demanding respect Police abuses against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the USA is published by: Amnesty International International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications, 2006 All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. - 2 - Copies of this report are available to download at www.amnesty.org For further information please see www.amnestyusa.org/outfront/ Printed by: The Alden Press Osney Mead, Oxford United Kingdom ISBN 0-86210-393-2 AI Index: AMR 51/001/2006 Original language: English - 3 - Preface 1 Methodology 1 Definitions 2 Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Identity-based discrimination -

Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline

The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline DEATH SENTENCES BY YEAR 3 Key Findings Peak: 315 in 1996 3 • Colorado becomes nd 22 state to abolish 2 death penalty 2 • Reform prosecutors gain footholds in 1 formerly heavy-use 1 death penalty counties 297 50 • Fewest new death 18 in 2020 sentences in modern 0 1973 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 era; state executions lowest in 37 years EXECUTIONS BY YEAR • Federal government 1 resumes executions Peak: 98 in 1999 with outlier practices, for first time ever 80 conducts more executions than all 60 states combined • COVID-19 pandemic 40 halts many 81 executions and court 2 proceedings; federal 17 in 2020 executions spark 0 1977 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 outbreaks The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report Introduction Death Row by State State 2020† 2019† 2020 was abnormal in almost every way, and that was clearly the case when it came to capital punishment in the United States. The California 724 729 interplay of four forces shaped the U.S. death penalty landscape in Florida 346 348 2020: the nation’s long - term trend away from capital punishment; the Texas 214 224 worst global pandemic in more than a century; nationwide protests Alabama 172 177 for racial justice; and the historically aberrant conduct of the federal North Carolina 145 144 administration. At the end of the year, more states had abolished the Pennsylvania 142 154 death penalty or gone ten years without an execution, more counties Ohio 141 140 had elected reform prosecutors who pledged never to seek the death Arizona 119 122 penalty or to use it more sparingly; fewer new death sentences were Nevada 71 74 imposed than in any prior year since the Supreme Court struck down Louisiana 69 69 U.S. -

Honor Killings in Turkey in Light of Turkey's Accession To

NOTE THEY KILLED HER FOR GOING OUT WITH BOYS: HONOR KILLINGS IN TURKEY IN LIGHT OF TURKEY’S ACCESSION TO THE EUROPEAN UNION AND LESSONS FOR IRAQ I. INTRODUCTION “We killed her for going out with boys.” 1 Sait Kina’s thirteen year old daughter, Dilber Kina, “talked to boys on the street” and repeatedly tried to run away from home. 2 In June 2001, during what would become her final attempt to leave, she was caught by her father in their Istanbul apartment. Using a kitchen knife and an ax, he beat and stabbed his daughter “until she lay dead in the blood-smeared bathroom of the . apartment.” 3 Kina then “commanded one of his daughters-in-law to clean up the [blood]” and had his sons discard the corpse. 4 Upon his arrest, Kina told authorities that he had “‘fulfilled [his] duty.’” 5 Kina’s daughter-in-law said, of the killing: “‘He did it all for his dignity.’” 6 “Your sister has done wrong. You have to kill her.”7 In a village in eastern Turkey, male family members held a meeting concerning the behavior of their twenty-five year old female family member. She, a Sunni Muslim, disobeyed her father by marrying a man who was an Alevi Muslim. Her father spent four months teaching his sixteen year old son how to hunt and shoot before he ordered his son to kill his own sister. The youth resisted, and was beaten. In fall 1999, he finally succumbed to this pressure, went to his sister’s home and shot her in the back while she was doing housework. -

Life Or Death for Child Homicide Updated April 2011

Life or Death for Child Homicide Updated April 2011 These are statutes that consider young age of a victim as a sole factor in determining whether a murderer should or must be sentenced as life imprisonment or death penalty. This compilation only includes statutes allowing for aggravated factors for death of a child and does not include statutes requiring a finding of child abuse. Jurisdictions that do not elevate the sentencing range to either life or death for the murder of children are left blank. Alabama...............................................................................................................................4 ALA. CODE §13A-5-40 (2010). Capital Offenses. ..........................................................4 ALA. CODE § 13A-5-45 (2010). Sentence hearing -- Delay; statements and arguments; admissibility of evidence; burden of proof; mitigating and aggravating circumstances.6 Alaska ..................................................................................................................................7 Arizona ................................................................................................................................7 ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 13-751 (2011). Sentence of death or life imprisonment; aggravating and mitigating circumstances; definition.....................................................7 Arkansas ............................................................................................................................11 ARK. CODE ANN. § 5-4-603 (2010). Death sentences, -

Constrictor Snake Incidents

constrictor snake incidents Seventeen people have died from large constrictor snake related incidents in the United States since 1978—12 just since 1990—including one person who suffered a heart attack during a violent struggle with his python and a woman who died from a Salmonella infection. Scores of adults and children have been injured during attacks by these deadly predators. Children, parents, and authorities are finding released or escaped pet pythons, boa constrictors, and anacondas all over the country, where they endanger communities, threaten ecosystems, and in many cases suffer tragic deaths. Following is a partial list of incidents, organized by various categories, involving constrictor snakes that have been reported in 45 states. Contents Read more Dangerous incidents Children and teenagers attacked or sickened by constrictor involving constrictor snakes snakes skyrocket Four babies sleeping in their cribs, as well as three other children have been squeezed to death by large constrictor snakes. Youngsters have 3 been attacked while playing in their yards, compressed to the point of unconsciousness, nearly blinded when bitten in the face, and suffered numerous other painful, traumatic, and disfiguring injuries. 34 incidents. Adults, other than the snake owner or caretaker, attacked or sickened by constrictor snakes Unsuspecting people have been attacked by escaped or released constrictor snakes while tending to their gardens, sleeping in their beds, 8 or protecting children and pets playing in their yards. One woman discovered an 8-foot python, who later bit an animal trapper she called, in her washing machine. 17 incidents. Owners and caretakers attacked by constrictor snakes Experienced reptile handlers and novices alike have been attacked by constrictor snakes, including an 8-month pregnant woman who feared both her and her baby were being killed by their pet snake and an elderly man on blood thinners who suffered dozens of deep puncture 11 wounds. -

Six Minutes Brennen Carl Brunner Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 Six minutes Brennen Carl Brunner Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brunner, Brennen Carl, "Six minutes " (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7080. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7080 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Six Minutes by Brennen Carl Brunner A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: Creative Writing Major Professor: Steven Pett Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 CHAPTER 1: STAND UP I ran again this afternoon after school, after my mother took me aside to tell me she was pregnant. "Things will be different/' she told me as she gave me a hug. "But not that different." I ran further than I usually do on weekdays, to the highway outside of town, and picked it up on the way back. I'm nauseous now, walking with my arms over my head at the end of the driveway, when I hear the screech of brakes and a whimper behind me. I spin and see a dog trotting away from the postal truck in the middle of the street, turning his head around to eye it as the driver inside coughs hoarsely and rubs his forehead. -

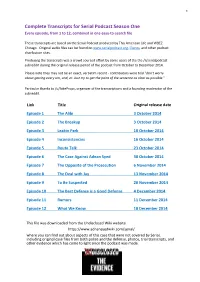

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

Condoning the Killin

Condoning the Killing Condoning the Killing 1. TREASURY POLICE EXECUTES TEN San Jose Las Flores March 1979 Department of Chalatenango Sedion 502 (a) (2): In March 1979 Army soldiers from the First Military Detachment seized Except under circumstances specified in 30 youths, aged 15 to 20, in San Jose Las Flores in the Department of this section, no security assistance may be Chalatenango. At the time the young men were playing socc~r. They were provided to any country which engages in taken to the barracks of the First Brigade in San Salvador. During the night a consistent pattern of gross violations of the commanding officer of the First Brigade called officers of the Treasury Police, the National Police and the National Guard to tell them that each of internationally recognized human rights. I the security forces would receive a group of the captured youths for The U.S. Foreign Assistance Ad of 1961 interrogation. The departmental head of the Treasury Police, Commander Dominguez, ordered Corporal Manuel Antonio Vanegas to choose a group of soldiers to bring ten of the young men to the Treasury Police headquarters. According to a deserter from the Treasury Police, Florentino Hernandez, the youths were severely beaten in order to force them to confess to belonging to the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN). The group of soldiers led by Corporal Vanegas and a Treasury Police instructor, Fernando Alvarado, returned to the Treasury Police headquarters without the young men. Hernandez has accused Corporal Vanegas and Alvarado of assassinating the youths. According to Hernandez, Corporal Vanegas later admitted that they had killed the young men outside the San Francisco sugar mill near the town of Aguilares in the Department of San Salvador. -

"On the Murder of Rickey Johnson": the Portland Police Bureau, Deadly Force, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Oregon, 1940 - 1975

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-12-2018 "On the Murder of Rickey Johnson": the Portland Police Bureau, Deadly Force, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Oregon, 1940 - 1975 Katherine EIleen Nelson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Nelson, Katherine EIleen, ""On the Murder of Rickey Johnson": the Portland Police Bureau, Deadly Force, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Oregon, 1940 - 1975" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4434. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6318 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. “On the Murder of Rickey Johnson”: The Portland Police Bureau, Deadly Force, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Oregon, 1940-1975 by Katherine Eileen Nelson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Marc Rodriguez, Chair Patricia Schechter David Johnson Darrell Millner Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Katherine Eileen Nelson i Abstract On March 14, 1975, twenty-eight year old Portland police officer Kenneth Sanford shot and killed seventeen-year-old Rickie Charles Johnson in the back of the head during a sting operation. Incredulously, Johnson was the fourth person of color to be shot and killed by Portland police within a five-month period.