Dato' Sri Mohd Najib Bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak Perdana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DC City Guide

DC City Guide Page | 1 Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States and the seat of its three branches of government, has a collection of free, public museums unparalleled in size and scope throughout the history of mankind, and the lion's share of the nation's most treasured monuments and memorials. The vistas on the National Mall between the Capitol, Washington Monument, White House, and Lincoln Memorial are famous throughout the world as icons of the world's wealthiest and most powerful nation. Beyond the Mall, D.C. has in the past two decades shed its old reputation as a city both boring and dangerous, with shopping, dining, and nightlife befitting a world-class metropolis. Travelers will find the city new, exciting, and decidedly cosmopolitan and international. Districts Virtually all of D.C.'s tourists flock to the Mall—a two-mile long, beautiful stretch of parkland that holds many of the city's monuments and Smithsonian museums—but the city itself is a vibrant metropolis that often has little to do with monuments, politics, or white, neoclassical buildings. The Smithsonian is a "can't miss," but don't trick yourself—you haven't really been to D.C. until you've been out and about the city. Page | 2 Downtown (The National Mall, East End, West End, Waterfront) The center of it all: The National Mall, D.C.'s main theater district, Smithsonian and non- Smithsonian museums galore, fine dining, Chinatown, the Verizon Center, the Convention Center, the central business district, the White House, West Potomac Park, the Kennedy Center, George Washington University, the beautiful Tidal Basin, and the new Nationals Park. -

'Demeaning,' 'Wonderful': Faculty Express Mixed Reactions on Culture Trainings Dining Partnership with D.C.-Based Food A

Monday, October 28, 2019 I Vol. 116 Iss. 13 AN INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER • SERVING THE GW COMMUNITY SINCE 1904 WWW.GWHATCHET.COM What’s inside Opinions Culture Sports The editorial board End spooky season Women’s soccer enters weighs in on right with The conference tournament proposals to forgive Hatchet’s Halloween with highest seeding student loan debt guide. since 2015 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Dining partnership with D.C.-based food app offers discounted meals LIA DEGROOT purchase meals from the food ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR trucks Monday will receive a free TwentyTables t-shirt, Students can now use Cohen said in an email to GWorld to purchase meal students Sunday. Sate Indone- tickets that can be used at sian, Peruvian Brothers, Ko- food trucks and restaurants rean Yellow Truck and Tazah around the District. Lebanese will be featured Offi cials partnered with at the Monday kick-off , the the founder of TwentyTables, email states. a company that teams up He said students can en- with D.C.-based food trucks ter an online contest to win and restaurants to donate a “golden ticket,” which pro- meals to charity for each item vides the winner with free purchased through the pro- lunch for a semester. gram. The program will pre- Cohen said giving stu- view Monday, during which dents the option to eat at food four food trucks participat- trucks on campus they previ- ing in TwentyTables will be ously didn’t have access to and stationed in Potomac Park for at establishments throughout lunch and dinner, and will of- the District combats “menu fi cially launch Wednesday, of- fatigue,” which occurs when fi cials said. -

Roadtrip Experience Movie Magic — for Free!

Proofed by: phadkep Time: 10:35 - 08-10-2007 Separation: C M Y K HIGH-RES PROOF. IMAGES ARE RIPPED. FULL PROOF INTEGRITY. Product: SOURCE LayoutDesk: SOU PubDate: 08-12-07 Zone: DC Edition: EE Page: RDTRIP C M Y K M6 SOURCE 08-12-07 DC EE M6 CMYK M6 Sunday, August 12, 2007 DC x The Washington Post RoadTrip Experience Movie Magic — for Free! Hang with the next- Jason Lee’s character made the drop to Will Smith’s character in “Enemy of the State” next generation of at a Dupont Circle storefront before biking to his demise on a nearby underpass. Brat Packers at the Q STREET Third Edition, Q STREET whose exterior was MASS. AVENUE 19TH STREET WISCONSIN used for the bar in DUPONT CIRCLE “St. Elmo’s Fire.” AVENU 33RD CONNECTICUT AVENUE STREET MPSHIRE E HA Georgetown AVENUE NEW 36TH STREET PROSPECT ST. M STREET M STREET honors Katharine National Theatre series The birthday with a film Hepburn’s 100th . lt closes at the Ronald Reagan Building Star sigh “On Golden Pond.” tings are guaranteed at Start K STREET 16TH STREET Monday with the National Portrait Gallery here which houses glossies of such , is Driver’s movie legends as Lucille Bal Gateway Park BRIDGE Rosslyn’s Potom ac R route Ronald Reagan and John Wayne.l, screening Clint Eastwood’s FRANCIS SCOTT KEY iver 17TH ST. tough-guy oeuvre on Fridays H STREET the end of the month. 9TH STREET through NORTH LYNN STREET 13TH STREET The guest with the best cowboy G STREET costume wins a prize. -

A Legacy of Leadership

A LEGACY OF LEADERSHIP Truly timeless, Four Seasons elevates hospitality to an art form POWER BEYOND POLITICS America’s great federal city is so much greater than you expect FOR SO MANY REASONS Can a city be among the coolest and the hottest in America? Yes, if it’s Washington, DC, according to Forbes and Business Insider magazines. Near the top of every must-see list, DC is more than its rich culture – museums, galleries and performing arts – or even its history and iconic memorials. The seductive food scene: restaurants to thriving craft breweries. Or parkland, more per capita than any city in the USA, and all the ways to enjoy it, year-round – from cherry blossom season to ice skating on the National Mall. LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR DESTINATION > HUGGING THE POTOMAC Georgetown Waterfront Park, steps from Four Seasons HISTORIC GEORGETOWN Its charming townhomes and cobblestone streets beside the famed C&O Canal give Georgetown a European feel. But its spirit is anything but old world. Take your morning run up the Exorcist Steps, spend after hours exploring the nightlife and, in between, visit Cady’s Alley design district, kayak on the Potomac or shop the city’s best boutiques. A landmark on Pennsylvania Avenue at the door to Georgetown, Four Seasons Hotel Washington, DC, is thirteen blocks from the White House and a stroll from two top universities. Many of the world’s most discerning travelers make Four Seasons their address of choice – for all the reasons they visit our city. LEARN MORE ABOUT GEORGETOWN > Hospitality at its best is timeless, without gimmick or pretense. -

Columnist Art Buchwald Selected As '79 Speaker by Greg Kitsock Fromlibya

Columnist Art Buchwald Selected as '79 Speaker by Greg Kitsock fromLibya. Calling Libya "probably the worst coun dents, faculty and administrators from each campus. recommending him, Caputo added. HOVA As~ocmte Editor try in the world when it comes to aiding terrorists," The group meets in October and November and sub Caputo said that after she submitted the three Humorist and political columnist Art Buchwald Buchwald offered to endow a chair in "Morality and mits recommendations to the President for com names to the honorary degree committee, she was will be this year's graduation speaker, The HOYA . Human Rights" if SFS Dean Peter Krogh took the mencement speakers and honorary degree recipients. told the Senior Week Committee would have no fur learned earlier this week. full course. According to Weidenbruch, its job ends there. The ther role in the selection process. Buchwald's acceptance was confirmed by his sec Buchwald withdrew his offer after a University Board of Directors reviews the suggestions and must "The (honorary degree) committee never got back retary, who said he received the invitation to speak forum on the issue was held, stating that he didn't authorize the University President to send out invi to me, and I have no information on whether they here just last week. Buchwald himself was on the want to interfere in Georgetown's affairs any further. tations. tried to get Trudeau or Bellow. I was not informed of West Coast and unavailable for comment. Peter Weidenbruch, cha'irman of the honorary de Buchwald was not among the twelve names sug the final choice," she claimed. -

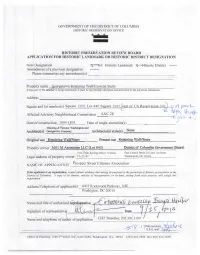

Georgetown Retaining Wall/Exorcist Steps

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: ____Georgetown Retaining Wall/Exorcist Steps_______________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ______N/A_____________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __Square 1202, Lot 840; East of Reservation 392__________________ City or town: _Washington________ State: __DC__________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________ ________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards -

Capital Traction Company Union Station 36001 and 3601 M Street NW Square 1203, Lot 47; Square 1202, Lot 840; and Part of the 36Th Street Right-Of-Way

HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD Historic Landmark Case No. 19-01 Capital Traction Company Union Station 36001 and 3601 M Street NW Square 1203, Lot 47; Square 1202, Lot 840; and part of the 36th Street right-of-way Meeting Date: January 24, 2019 Applicant: Prospect Street Citizens Association and D.C. Preservation League Affected ANC: 2E The Historic Preservation Office recommends that the Board designate the Capital Traction Company Union Station a historic landmark in the D.C. Inventory of Historic Sites, and that the Board request that the nomination be forwarded to the National Register of Historic Places for listing as of local significance, with a period of significance of 1894 to 1973, the era of its construction and its use by the Capital Traction Company and the Capital Transit Company. The property merits designation under National Register Criteria A and C and District of Columbia Criteria B (“History”) and D (“Architecture and Urbanism”) as one of the of the best examples of a streetcar depot and barn built or extant in Washington and perhaps the most important of them all. The majority of Washington’s streetcar barns and stables have been destroyed in whole or in greater part. This is one of perhaps eight terminals that remain, some of which date much later and are more closely associated with bus storage. It is a handsome and imposing station, unique in that it initially accommodated three independent streetcar lines that served the District and northern Virginia and that employed both cable and electric propulsion. It tells the story of the conversion of streetcars from horse to cable to electric propulsion. -

View/Open: 1975-08-30.Pdf

56th Year, No.1 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Saturday, August 30, 1975 Board Restricts Age Of Current Officers by Barry Wiegand Charles O. Rossotti, a member retire at age 65, however only and Wayne Saitta of the board, said that "in light of recently has the policy been The University Board of Direc the resolution, we will have to rigorously enforced. Several fac tors at its May meeting agreed to appoint a search committee." He ulty members currently teachmg include all University officers in added that "that has not been courses are over the retirement its retirement at age 65 policy, done yet" but that the board will age. stipulating that nobody currently do so "at some point allowing Retirement policy for Univer serving could remain past age 67. enough time to find a new sity officers who served at the Sources close to the board president." pleasure of the Board of Directors added that the Board of Directors Fr. Henle said in an interview had also been unclear. agreed to establish a search this week that the Board or" Fr. Henle returned to work committee for a new President in Directors had such a policy, but Thursday after spending several University President the Rev. R. J. Henle, S.J., will be affected by a January since University president that "the rule involved the policy w e e ks recuperating from an new University policy that requires all emplovees over 65 to retire R. J. Henle, S.J. will be 66 on of employment after 65, with the operation for glaucoma he under when they are 67. -

Georgetown Rosslyn

FEASIBILITY STUDY Context GEORGETOWN GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY 1920’s View - Aqueduct & Key Bridge 37th ST NW ST 37th NW 36th ST NW ST 35th NW 34th ST NW ST 33rd C&O CANAL M STREET NW WHITEHURST FRWY WISCONSIN AVE NW AVE WISCONSIN POTOMAC RIVER WATERFRONT PARK Top of “The Exorcist Steps” KEY BRIDGE GW PARKWAY View from Key Bridge I-66 GATEWAY PARK ROOSEVELT ISLAND ROSSLYN View from Key Bridge Marriot N MOORE ST ST N LYNN N FORT MYER DR WILSON BLVD View of Rosslyn from Aqueduct Ruins I-66 ARLINGTON BLVD US MARINE CORPS WAR MEMORIAL N MEADE ST View from Gateway Park N Fort Myer Dr - Looking North N Moore St - Looking North N Lynn St - Looking North FINAL-GR-Gondola-PMBoards.indd 1 7/7/2016 9:15:33 AM DESIGN AND ENGINEERING Gondola Examples Gondola Loading Area View of Gondola Interior View of Tram Interior London, UK Koblenz, Germany Tbilisi, Georgia Barcelona Singapore South Korea Turkey London Portland Aerial Tram, Oregon New York City, Roosevelt Island Tram FINAL-GR-Gondola-PMBoards.indd 2 7/7/2016 9:15:43 AM TRANSPORTATION Existing Transportation and Future Transit Plans WISCONSIN AVE NW GEORGETOWN Capital Bikeshare GUTS Bus - Daily North - 959 South - 959 37th ST NW ST 37th NW 36th ST NW ST 35th NW 34th ST NW ST 33rd C&O CANAL Metro 2040 Plan Metro 2040 Plan Potential Station Potential Station M STREET NW Pedestrian and Bike Paths to Key Bridge WHITEHURST FRWY POTOMAC RIVER DC Streetcar Pedestrians - Daily Georgetown to Union Station North - 1,667 South - 1,692 KEY BRIDGE GW PARKWAY Bike - Daily North - 723 Streetlight Auto Trip South - 734 Analysis Zones - Daily North - 2,098 South - 451 GATEWAY PARK I-66 DC Circulator - Daily North - 546 South - 546 Potential Metro ROSSLYN WMATA 38b - Daily North - 500 Existing South - 500 Rail Origin-Destination Data Travel Between Foggy Bottom N FORT MYER DR MYER FORT N and Courthouse/Rosslyn North - 1,849 South - 1,792 N MOORE ST WILSON BLVD N LYNN ST N LYNN ARLINGTON BLVD GOALS • Provide a seamless transition from Metro to Gondola, both in regards to wait time, physical connection, transfers and ticketing. -

Agency Outlines Stormwater Plans Runoff Into the Potomac River and of Sewage Overflow Tunnels

Wednesday, November 4, 2015 Serving Burleith, Foxhall, Georgetown, Georgetown Reservoir & Glover Park Vol. XXV, No. 14 The GeorGeTown CurrenT L I TTLE HEROES Agency outlines stormwater plans runoff into the Potomac River and of sewage overflow tunnels. ■ Infrastructure: Residents Rock Creek. Residents have generally been Planners shared details for the supportive of green infrastructure raise concerns about impacts latest iteration of the D.C. Water and measures that have multiple envi- By KELSEY KNORP Sewer Authority’s $2.6 billion plan ronmental benefits, as opposed to Current Correspondent at a community meeting Oct. 7. The costly and disruptive tunnels. But agency, also known as DC Water, permeable streets in Georgetown The latest phase of the D.C. evaluated several options for the will need more care than many resi- Clean Rivers Project will require federally mandated project and dents are used to — sweeping is street sweeping in parts of George- determined that the most cost-effec- necessary to prevent growth of town and Glover Park following the tive option would be to install pervi- weeds from below and potential installation of “green infrastructure” ous pavement on various streets to clogs from above, planners said — to minimize harmful stormwater complement a long-planned system See Green/Page 4 GU Hospital plans win nod from ANC By BRADY HOLT Current Staff Writer A new $560 million building planned at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital’s campus won signifi- cant community support Monday following an agree- ment governing traffic, construction and noise impacts on the surrounding neighborhoods. The Georgetown advisory neighborhood commission unanimously supported the hospital’s certificate of need application, in which MedStar must persuade city health officials that a major investment is valuable to the Dis- Current file photo trict and doesn’t duplicate other hospitals’ offerings. -

Exploring Washington, D.C. Travel Guide & Staff Tips GENERAL GUIDES

Childhood Injury Prevention Convention July 17 - 20, 2019 Washington, D.C. Exploring Washington, D.C. Travel Guide & Staff Tips GENERAL GUIDES Fodors - https://www.fodors.com/world/north-america/usa/washington-dc Lonely Planet - https://www.lonelyplanet.com/usa/washington-dc Trip Advisor - https://www.tripadvisor.com/Travel_Guide-g28970-Washington_DC_District_of_Columbia.html Smithsonian - https://www.si.edu/ (Including the National Zoo) GETTING AROUND Metro The Washington, D.C. Metro offers an easy and convenient way to get around the greater D.C. area. At the website you will find a map and trip planning tool to help you get from point A to point B. The Marriott Marquis, the site of PrevCon 2019, is conveniently located on the following metro lines: Gallery Place/Chinatown (Red Line) 0.5 miles SE from Hotel Mt. Vernon Square 7th Street/Convention Center (Green & Yellow Lines) 0.1 miles East from Hotel Kim’s Tips for Using the Metro Skip the line and get your rechargeable metro SmarTrip card before you arrive! Allow 4 to 6 weeks for delivery. Order at https://smartrip.wmata.com/Storefront\ SmarTrip cards are refillable cards you can use on just about every transit provider in the D.C. metro area—including the bus, light rail, subway, and even the transit lines to popular D.C. suburbs in Maryland and Virginia. Buy one before your trip; you can always add to it throughout your stay. A one-day unlimited pass is just $14.75, which is a great value if you plan to see a lot of different parts of the city.https://www. -

Newslettermarch 2017

NewsletterMARCH 2017 VOLUME XLII | ISSUE 3 | WWW.CAGTOWN.ORG Georgetown Beautification: TALKING TRASH (& RODENTS) WEDNESDAY, MARCH 22 framework of the Georgetown Community RECEPTION AT 7PM; PROGRAM AT 7:30 PM Partnership. HEALY FAMILY CENTER – The speakers on March 22 will be: Gerard GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CAMPUS Brown, the Program Manager in the Rodent Control Division at the DC Department of Patrick Clawson, Co-Chair: Rats, Trash & Recycling Health; Sonya Chance, the Ward 2 inspector for the DC Department of Public Works’ wo of the most frequently cited con- Solid Waste Education and Enforcement Pro- cerns in our recent member survey gram (SWEEP), and Cory Peterson from Twere rats and trash. At our Wednesday, Georgetown University’s Office of Neigh- March 22 meeting, a panel of experts will borhood Life. discuss what can be done to combat these persistent problems. Our host for the evening is Georgetown Uni- versity. The meeting will be held in the Social Georgetown is a lovely neighborhood not Room of the Healy Family Student Center. only for people but, unfortunately, also Come for an informative discussion and for rodents. Hear why our village has so check out this modern, attractive facility. A many rats and what you can do to help the reception will begin at 7pm, followed by the DC Department of Health reduce the rat panel discussion at 7:30. population. The Healey Family Student Center is on the In the last few years, both the DC Govern- south side of campus. For directions (walking, ment and Georgetown University have devot- driving, cycling), see maps.georgetown.edu.