Rural Microbusinesses in North East England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alnwick District Council

APPENDIX 1 APPENDIX 1 ALNWICK DISTRICT COUNCIL MEETING OF THE COUNCIL JUBILEE HALL, ROTHBURY TUESDAY, 16TH OCTOBER, 2007 AT 6.30 P.M. PRESENT: Councillors P. Dawson (Chairman), Mrs. A.M. Jones (Vice- Chairman), G.R. Arckless, Mrs. E. Bainbridge, L.G. Bilboe, E.M. Blakey, S.C. Bridgett, G. Castle, K. Gray, Miss C. Grey, Mrs. M.E. Haddow, A.M. Harrington, J.M. Hedley, I. Hinson, J.E. Hobrough, J.M. Hope, C.M. Mills, Mrs. M. Mills, H.W. Philipson, D.J.C. Rixon, T.M. Spence, R. Styring, J.A. Taylor, T.N. Thorne, J.G. Watson. Officers: Chief Executive, Director of Environment and Regeneration, Head of Legal and Democratic Services. Apologies: Councillors S.A. Bell, Mrs. S.E. Bolam, Mrs. Z.B. Frais, Mrs. E. Gray. Aldermen J. Hobson and R.H. Huggins. (* Denotes a Delegated Matter) 189. DISCLOSURE OF INTERESTS BY MEMBERS AND OFFICERS The Chairman reminded Members that it had been agreed that previous disclosures did not need to be made again at the Council meeting provided that this was agreed by Members after a motion had been moved and seconded. RESOLVED: that all disclosures of interest previously made by Members and Officers at the meetings of Committees, etc., the minutes of which are to be considered at this meeting, are also to be regarded as disclosures for the purposes of this meeting by those Members and Officers present. The Chairman also advised that interests should be disclosed at this meeting:- a) if they were not disclosed at previous meetings, the minutes of which were to be considered at this meeting or b) in respect of any other or new item on the Agenda. -

2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No. 2) Order 2004 Made - - - - 6th December 2004 Laid before Parliament 10th December 2004 Coming into force - - 31st December 2004 The First Secretary of State, having received a report from the Audit Commission(a) produced under section 99(1) of the Local Government Act 2003(b), in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 99(4) of that Act, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No.2) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 31st December 2004. (2) This Order applies in relation to English local authorities(c). Categorisation report 2. The English local authorities, to which the report of the Audit Commission dated 8th November 2004 relates, are, by this Order, categorised in accordance with their categorisation in that report. Excellent authorities 3. The local authorities listed in Schedule 1 to this Order are categorised as excellent. Good authorities 4. The local authorities listed in Schedule 2 to this Order are categorised as good. Fair authorities 5. The local authorities listed in Schedule 3 to this Order are categorised as fair. (a) For the definition of “the Audit Commission”, see section 99(7) of the Local Government Act 2003. (b) 2003 c.26. The report of the Audit Commission consists of a letter from the Chief Executive of the Audit Commission to the Minister for Local and Regional Government dated 8th November 2004 with the attached list of local authorities categorised by the Audit Commission as of that date. -

Northumberland County Council Transport Assessment Mitigation Report (January 2019) ● the Northumberland Local Transport Plan (2011-2026)

Local Impact Report A1 in Northumberland [blank page] 2 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Northumberland Context 3. Details of the Proposal 4. Local and National Development Plans and Policy 5. Assessing the A1 Dualling Proposal in the Northumberland Planning Policy Context 6. Local Impacts Assessment 6.1 Pre-amble 6.2 Economic Growth and Transportation 6.3 Noise and Vibration 6.4 Air Quality 6.5 Landscape and Visual Impacts 6.6 Cultural Heritage 6.7 Biodiversity 6.8 Road Drainage and Flood Risk 6.9 Geology and Soils 6.10 Materials 6.11 Construction Traffic 6.12 Road Safety 7. Consideration of the Impact of the Proposed Provisions and Requirements within the Draft Development Consent Order 8. Conclusion Appendix 1: Landscape Sensitivity Assessment Appendix 2: Effects on landscape character Appendix 3: Visual receptors – Key references within the ES 3 1. Introduction 1.1 A Local Impact Report (LIR) is defined according to Section 60(3) of the Planning Act 2008 as ‘a report in writing giving details of the likely impact of the proposed development on the authority’s area.’ It should be used by Local Authorities as the means by which their existing body of knowledge and evidence of local issues can be fully and robustly reported to the Examining Authority. It should draw on existing local knowledge and experience. 1.2 This is a Local Impact Report relating to the application by Highways England to upgrade the A1 north of Morpeth to dual carriageway in two sections – Morpeth to Felton and Alnwick to Ellingham. This report has been produced in accordance with Version 2 of the Local Impact Report Guidance (the Advice Note) produced by The Planning Inspectorate dated April 2012 and considers the likely impacts of the proposed development on Northumberland, being the Local Authority within whose administrative area the works will take place. -

Berwick Upon Tweed and Its Connections with England and Scotland: a Survey of Work and Commuting Patterns

Berwick upon Tweed and its connections with England and Scotland: A survey of work and commuting patterns Jane Atterton Final Report prepared for Berwick upon Tweed Borough Council June 2008 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Introduction 5 3. Aim and objectives of the study 6 4. Literature and policy review 7 4.1 Introduction 7 4.2 Commuting in Britain 7 4.3 City regions and rural areas in England and Scotland 12 4.4 Summary 14 5. Regional and local context: Northumberland, the Scottish Borders and the Borough of Berwick upon Tweed 15 5.1 Introduction 15 5.2 Northumberland 15 5.3 The Scottish Borders 15 5.4 Case study: The Borough of Berwick upon Tweed 18 6. Study methodology 22 7. Results 23 7.1 Introduction 23 7.2 Characteristics of respondents 23 7.3 The commuting behaviour of respondents 26 7.4 The impact of commuting on respondents’ lifestyles 29 7.5 The residential and employment preferences of respondents 33 7.6 Respondents’ perceptions of Berwick Borough and its future development 37 8. Conclusions 41 9. References 45 10. Appendices 48 2 1. Executive Summary • Recent research has highlighted an increasing separation of work and residential location as commuting journey lengths increase. This is particularly the case for rural residents, who tend to have longer commutes than urban residents. Whilst commuters bring money to their place of residence that has been earned outside the locality, they also represent a leakage of money from the locality often commuting for work is associated with commuting for other activities, including retail and leisure spending. -

Community Research in Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 2003

Community Research in Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 2003 Research Study Conducted for The Boundary Committee for England October 2003 Contents Introduction 1 Executive Summary 4 Local Communities 6 Defining Communities 6 Identifying Communities 6 Identity with the Local Community in the Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 7 Overall Identity 7 Effective Communities 9 Involvement 13 Affective Communities 16 Bringing Effective and Affective Communities Together 17 Local Authority Communities 19 Belonging to Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 19 Belonging to Northumberland County Council Area 22 Knowledge and Attitudes towards Local Governance 25 Knowledge of Local Governance 25 Involvement with Local Governance 26 Administrative Boundary Issues 26 Appendices 1. Methodology – Quantitative 2. Methodology - Qualitative 3. Sub-Group Definitions 4. Place Name Gazetteer 5. Qualitative Topic Guide 6. Marked-up Questionnaire Community Research in Castle Morpeth Borough Council Area 2003 for The Boundary Committee for England Introduction Research Aims This report presents the findings of research conducted by the MORI Social Research Institute on behalf of The Boundary Committee for England (referred to in this report as "The Committee") in the Castle Morpeth Borough Council area. The aim of this research is to establish the patterns of community identity in the area. Survey Coverage MORI has undertaken research in all 44 two-tier district or borough council areas in the North East, North West and Yorkshire and the Humber regions. The research covers two-tier local authority areas only; the results may however identify issues which overlap with adjacent areas. Reports and data for other two-tier areas are provided under separately. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF TYNE AND WEAR THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF GATESHEAD Boundaries with: CASTLE MORPETH and TYNEDALE in NORTHUMBERLAND DERWENTSIDE and CHESTER-LE-STREET in COUNTY DURHAM CASTLE MORPETH NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE SOUTH TYNESIDE TYNEDALE GATESHEAD DERWENTSIDE CHESTER -LE-STREET REPORT NO. 640 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 640 SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF TYNE AND WEAR THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF GATESHEAD AND ITS BOUNDARIES WITH THE DISTRICTS OF CASTLE MORPETH AND TYNEDALE IN NORTHUMBERLAND, AND WITH THE DISTRICTS OF DERWENTSIDE AND CHESTER-LE-STREET IN COUNTY DURHAM COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 1. This is one of a series of five reports dealing with the metropolitan districts of Tyne and Wear. In each of these reports we firstly set out our analysis of those proposals put to us for radical change to the County as a whole, and then our consideration of the boundaries of the particular metropolitan district under review. 2. The five reports are as follows:- (i) Gateshead, and its boundaries with Castle Morpeth and Tynedale in Northumberland and Derwentside and Chester-le- Street in County Durham. (ii) Newcastle upon Tyne. and its boundaries with Gateshead and with Castle Morpeth in Northumberland. (iii) North Tvneside. and its boundaries with Newcastle upon Tyne and with Blyth Valley and Castle Morpeth in Northumberland. (iv) South Tyneside. and its boundaries with Gateshead, Newcastle upon Tyne, North Tyneside and Sunderland. (v) Sunderland, and its boundaries with Gateshead, with the City of Durham, Chester-le-Street and Easington in County Durham. -

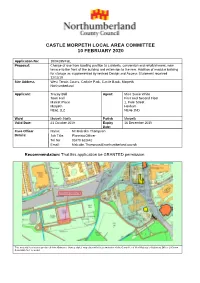

Castle Morpeth Local Area Committee 10 February 2020

CASTLE MORPETH LOCAL AREA COMMITTEE 10 FEBRUARY 2020 Application No: 19/04195/FUL Proposal: Change of use from bowling pavilion to cafeteria, conversion and refurbishment, new terrace to the front of the building and extension to the rear. Addition of modular building for storage as supplemented by revised Design and Access Statement received 12/11/19 Site Address West Tennis Courts, Carlisle Park, Castle Bank, Morpeth Northumberland Applicant: Tracey Bell Agent: Miss Susie White Town Hall First And Second Floor Market Place 1, Fore Street Morpeth Hexham NE61 1LZ NE46 1ND Ward Morpeth North Parish Morpeth Valid Date: 21 October 2019 Expiry 16 December 2019 Date: Case Officer Name: Mr Malcolm Thompson Details: Job Title: Planning Officer Tel No: 01670 622641 Email: [email protected] Recommendation: That this application be GRANTED permission This material has been reproduced from Ordnance Survey digital map data with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright (Not to Scale) 1. Introduction 1.1 This application is being reported to the Local Area Committee as the proposal has been submitted on behalf of Morpeth Town Council and relates to land owned by Northumberland County Council. 2. Description of the Proposals 2.1 The application seeks planning permission for refurbishment and a change of use of the existing bowling pavilion situated within Carlisle Park to a cafeteria along with the following: - minor alterations to elevations; - provision of new terrace to front; - small extension upon rear; and - siting of portable office/store to rear. 2.2 The application has been submitted following the earlier submission of a pre-application enquiry when a favourable response was offered. -

UK Survey Report MORPETH Prepared By

MICRODIS: Integrated Health, Social and Economic Impacts of Extreme Events: Evidence, Methods and Tools UK Survey Report MORPETH Photo source: Alan Purdue Prepared by: UK Country Team, Northumbria University January 2010 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Background to the Field Site 3 2.1 Geography 3 2.2 Population 5 2.3 Economy 6 2.4 Disaster context 7 2.4.1 Disaster history 7 2.4.2 The September 2008 flood 9 3. Methodology 11 3.1 The quantitative survey 12 3.1.1 Sampling 12 3.1.2 Questionnaire adaptation 12 3.1.3 Interviewers 14 3.2 Qualitative fieldwork and community engagement 14 4. Challenges and Achievements 17 5. Preliminary Field Observations and results 18 References 20 - 2 - 1. Introduction Flooding has become a major concern in the UK, particularly since the widespread summer floods of 2007, which flooded 55,000 properties and caused billions of pounds of damage; 13 people lost their lives and around 7,000 people had to be rescued (Pitt, 2008). The Environment Agency’s 2008 National Flood Risk Assessment shows there are currently 2.4 million properties at risk from fluvial and coastal flooding in England. A preliminary assessment of surface water flood risk suggests that one million of these properties are also susceptible to surface water flooding with a further 2.8 million properties susceptible to surface water flooding alone. Overall, around 5.2 million properties in England, or one in six properties, are at risk of flooding. The expected annual damages to residential and non-residential properties in England at risk of flooding from rivers and the sea is estimated at more than £1 billion. -

Region Variables

National Child Development Study Revised Region Variables Jane Elliott, Jon Johnson and Peter Shepherd User guide to the data (Third Edition) March 2012 Centre for Longitudinal Studies Following lives from birth through the adult years 1 www.cls.ioe.ac.uk CLS is an ESRC Resource Centre based at the Institute of Education, London First published in 2009 by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies Institute of Education, University of London 20 Bedford Way London WC1H 0AL www.cls.ioe.ac.uk © Centre for Longitudinal Studies The Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS) is an ESRC Resource Centre based at the Institution of Education. It provides support and facilities for those using the three internationally-renowned birth cohort studies: the National Child Development Study (1958), the 1970 British Cohort Study and the Millennium Cohort Study (2000). CLS conducts research using the birth cohort study data, with a special interest in family life and parenting, family economics, youth life course transitions and basic skills. The views expressed in this work are those of the author(s) (amend as necessary) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic and Social Research Council. All errors and omissions remain those of the author(s). This document is available in alternative formats. Please contact the Centre for Longitudinal Studies. tel: +44 (0)20 7612 6875 email: [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

LOCALAREA WARDNAME SCH NAME YEAR TYPE Ashington

LOCALAREA WARDNAME SCH_NAME YEAR_TYPE Ashington - Blyth Ashington Central Central Primary School Primary Ashington - Blyth College Northumberland College Further Education Ashington - Blyth Cowpen Malvin's Close Primary Academy Primary Ashington - Blyth Cowpen Morpeth Road Primary Academy Primary Ashington - Blyth Haydon St Aidan's RC Voluntary Aided First First Schools Ashington - Blyth Isabella Bede Academy Academy Ashington - Blyth Isabella St Wilfrid's RC Voluntary Aided Primary Primary Ashington - Blyth Kitty Brewster The Blyth Academy High Schools Ashington - Blyth Kitty Brewster Horton Grange Primary School Primary Ashington - Blyth Kitty Brewster The Dales School Special Schools Ashington - Blyth Newsham Newsham Primary School Primary Ashington - Blyth Newsham New Delaval Primary School Primary Ashington - Blyth Seaton with Newbiggin West The Northumberland C of E Academy Academy Ashington - Blyth Seaton with Newbiggin West St Benedict's RC Voluntary Aided Middle School Middle Schools Ashington - Blyth Sleekburn Bedlingtonshire Community High School High Schools Ashington - Blyth Sleekburn Bedlington Station Primary School Primary Ashington - Blyth Sleekburn Cambois Primary School Primary Ashington - Blyth Wensleydale Croftway Primary Academy Primary Castle Morpeth Bothal Ashington Community High School Sports College High Schools Castle Morpeth Bothal Bothal Primary School Primary Castle Morpeth Choppington Mowbray Primary School Primary Castle Morpeth Choppington Choppington Primary School Primary Castle Morpeth Choppington Cleaswell Hill School Special Schools Castle Morpeth Druridge Bay Grange View C of E Vol Controlled First School First Schools Castle Morpeth Druridge Bay Broomhill First School First Schools Castle Morpeth Druridge Bay Red Row First School First Schools Castle Morpeth Longhorsley Longhorsley St Helen's C of E First School First Schools Castle Morpeth Longhorsley Cambo First School First Schools Castle Morpeth Longhorsley Nunnykirk School Non Maintained Spec. -

The Impact of Recession on Northern City Regions:Layout 1.Qxd

WWW.IPPR.ORG/NORTH TheImpactofthe RecessiononNorthern City-Regions ByTonyDolphin October2009 ©ippr2009 2 ipprnorth|TheImpactoftheRecessiononNorthernCity-Regions Aboutipprnorth ipprnorth,theNewcastle-basedofficeoftheInstituteforPublicPolicyResearch,produces far-reachingpolicyideas,stimulatingsolutionsthatworknationallyaswellaslocally.These areshapedfromourresearch,whichspanseconomicdevelopment,regeneration,public servicesanddevolutionaswellasastrongdemocraticengagementstrandwhichinvolvesa widerangeofaudiencesinpoliticaldebates. ipprnorth,2ndFloor,20CollingwoodStreet,NewcastleUponTyneNE11JF Tel+44(0)1912339050|www.ippr.org/north RegisteredCharityNo.800065 ThispaperwasfirstpublishedinOctober2009.©ipprnorth2009 Abouttheproject Thispaperwasoriginallypreparedaspartoftheevidencebaseforthe‘MakingCityRegions WorkforDeprivedCommunities’project,amajorprogrammeofworkbeingundertakenby ipprnorth,withtheJosephRowntreeFoundationandtheNorthernWay.Itaimsto understandwhy,earlierinthisdecade,someareaswithincity-regionsintheNorthof Englandremaineddeprivedevenwhenthesurroundingeconomywasperformingstrongly;to explorehowdeprivedareascanbebetterlinkedtoareasofeconomicopportunity;to considertherolesoflocal,city-regional,regionalandnationalbodiesandtoinformthenext generationofpoliciestargetedatdeprivedcommunities. Theviewsexpressedinthispaperarethoseoftheauthorandnotnecessarilythoseofippr north,theJosephRowntreeFoundationortheNorthernWay. 3 ipprnorth|TheImpactoftheRecessiononNorthernCity-Regions Executivesummary ThispaperlooksatthegeographicaleffectoftherecessionacrosstheUnitedKingdomand, -

Transforming Trowbridge Masterplan Development Stage One - Scoping and Vision Study

Transforming Trowbridge Masterplan Development Stage One - Scoping and Vision Study Final Report - August 2010 2 TRANSFORMING TROWBRIDGE | Masterplan Development Stage One - Scoping and Vision Study | August 2010 TRANSFORMING TROWBRIDGE Masterplan Development Stage One Scoping and Vision Study CONTENTS Executive Summary 5 1. Introduction 10 2. Understanding Trowbridge 14 3. Stakeholder consultation 41 4. Transforming Trowbridge - the vision 48 5. Transforming Trowbridge - guiding principles 50 6. Transforming Trowbridge - area framework 74 7. Conclusions and next steps 99 TRANSFORMING TROWBRIDGE | Masterplan Development Stage One - Scoping and Vision Study | August 2010 3 Executive summary Introduction © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. License No. 100022961 This Scoping and Vision Report has been commissioned to inform the development of a masterplan for Trowbridge Town Centre. Trowbridge currently has a number of large vacant sites around the town centre, and has been identifi ed as an area suitable for growth by Wiltshire Council and regional planning bodies. The Scoping and Visioning exercise and the masterplan to follow therefore have a key role to play in shaping the future development of Trowbridge. Understanding Trowbridge A review of Trowbridge was undertaken which included the following aspects: • Strategic context; • Demographics; • Economy; • Shopping; • Legibility; and • Historic context. The key fi ndings of this review are set out on the adjacent page, along with the implications this has for the production of the masterplan. Preferred strategic site option for Trowbridge, Wiltshire Core Strategy 2009 4 TRANSFORMING TROWBRIDGE | Masterplan Development Stage One - Scoping and Vision Study | August 2010 Socio-economic and planning and which spend money on food, fi ne provides an opportunity to help deliver the environment of the core through context wine, clothing, home furnishings, golf, new services and facilities which are seeking to reduce the dominance of gardening and travel.