Early Medieval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (Ldp) Proposed Rural Housing

MONMOUTHSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN (LDP) PROPOSED RURAL HOUSING ALLOCATIONS CONSULTATION DRAFT JUNE 2010 CONTENTS A. Introduction. 1. Background 2. Preferred Strategy Rural Housing Policy 3. Village Development Boundaries 4. Approach to Village Categorisation and Site Identification B. Rural Secondary Settlements 1. Usk 2. Raglan 3. Penperlleni/Goetre C. Main Villages 1. Caerwent 2. Cross Ash 3. Devauden 4. Dingestow 5. Grosmont 6. Little Mill 7. Llanarth 8. Llandewi Rhydderch 9. Llandogo 10. Llanellen 11. Llangybi 12. Llanishen 13. Llanover 14. Llanvair Discoed 15. Llanvair Kilgeddin 16. Llanvapley 17. Mathern 18. Mitchell Troy 19. Penallt 20. Pwllmeyric 21. Shirenewton/Mynyddbach 22. St. Arvans 23. The Bryn 24. Tintern 25. Trellech 26. Werngifford/Pandy D. Minor Villages (UDP Policy H4). 1. Bettws Newydd 2. Broadstone/Catbrook 3. Brynygwenin 4. Coed-y-Paen 5. Crick 6. Cuckoo’s Row 7. Great Oak 8. Gwehelog 9. Llandegveth 10. Llandenny 11. Llangattock Llingoed 12. Llangwm 13. Llansoy 14. Llantillio Crossenny 15. Llantrisant 16. Llanvetherine 17. Maypole/St Maughans Green 18. Penpergwm 19. Pen-y-Clawdd 20. The Narth 21. Tredunnock A. INTRODUCTION. 1. BACKGROUND The Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (LDP) Preferred Strategy was issued for consultation for a six week period from 4 June 2009 to 17 July 2009. The results of this consultation were reported to Council in January 2010 and the Report of Consultation was issued for public comment for a further consultation period from 19 February 2010 to 19 March 2010. The present report on Proposed Rural Housing Allocations is intended to form the basis for a further informal consultation to assist the Council in moving forward from the LDP Preferred Strategy to the Deposit LDP. -

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Week 31/05/2014 to 06/06/2014 Print Date 09/06/2014 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Caerwent DC/2013/01065 Proposed new stone boundary walls & timber personnel gates providing improved security Planning Permission adjacent public highway. Original extant permission ref no. M/1232. Brook House Cottage Mr B McCusker & Mrs L Winterbourne Buckle Chamberlain Partnership Crick Brook Cottage Mill House Chepstow Crick Llancayo Court NP26 5UW Chepstow Llancayo NP26 5UW Usk NP15 1HY Caerwent 23 May 2014 348,877 / 190,201 DC/2014/00643 DC/2013/00670 - Discharge of condition 5 (Programme of archaeological work). Discharge of Condition Five Lanes Farm William Jones Lyndon Bowkett Designs Five Lanes Carrow Hill Farm 72 Caerau Road Caerwent Carrow Hill Newport Caldicot St Brides NP20 4HJ NP26 5PE Netherwent Caldicot NP26 3AU Caerwent 28 May 2014 344,637 / 190,589 DC/2014/00113 Outline application for dwelling at the rear of myrtle cottage Outline Planning Permission Myrtle Cottage Mrs Gail Harris James Harris The Cross Myrtle Cottage Myrtle Cottage Caerwent The Cross The Cross Caldicot Caerwent Caerwent NP26 5AZ Caldicot Caldicot NP26 5AZ NP26 5AZ Caerwent 03 June 2014 346,858 / 190,587 Caerwent 3 Print Date 09/06/2014 MCC Pre Check of Registered Applications 31/05/2014 to 06/06/2014 Page 2 of 15 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Dixton With Osbaston DC/2013/00946 Seperation of the property into two dwellings. -

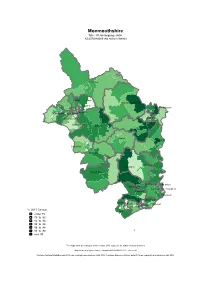

Monmouthshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Monmouthshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Crucorney Cantref Mardy Llantilio Crossenny Croesonen Lansdown Dixton with Osbaston Priory Llanelly Hill GrofieldCastle Wyesham Drybridge Llanwenarth Ultra Overmonnow Llanfoist Fawr Llanover Mitchel Troy Raglan Trellech United Goetre Fawr Llanbadoc Usk St. Arvans Devauden Llangybi Fawr St. Kingsmark St. Mary's Shirenewton Larkfield St. Christopher's Caerwent Thornwell Dewstow Caldicot Castle The Elms Rogiet West End Portskewett Green Lane %, 2011 Census Severn Mill under 79 79 to 82 82 to 84 84 to 86 86 to 88 88 to 90 over 90 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Monmouthshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Crucorney Mardy Llantilio Crossenny Cantref Lansdown Croesonen Priory Dixton with Osbaston Llanelly Hill Grofield Castle Drybridge Wyesham Llanwenarth Ultra Llanfoist Fawr Overmonnow Llanover Mitchel Troy Goetre Fawr Raglan Trellech United Llanbadoc Usk St. Arvans Devauden Llangybi Fawr St. Kingsmark St. Mary's Shirenewton Larkfield St. Christopher's Caerwent Thornwell Caldicot Castle Portskewett Rogiet Dewstow Green Lane The Elms %, 2011 Census West End Severn Mill under 1 1 to 2 2 to 2 2 to 3 3 to 4 4 to 5 over 5 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 -

Oja19-4Howell 387..395

RAYMOND HOWELL THE DEMOLITION OF THE ROMAN TETRAPYLON IN CAERLEON: AN ERASURE OF MEMORY? Summary. Excavations in Caerleon, the headquarters of the Second Augustan Legion, have demonstrated the existence of a tetrapylon at the centre of the Roman fortress. Evidence indicates that the structure survived into the medieval period when it was undermined and demolished. A recent review of ceramic finds associated with the demolition horizon suggests that the tetrapylon was razed in the thirteenth century. While stone-robbing for reconstruction of the medieval castle in Caerleon may provide a partial explanation for the destruction, political circumstances at the time provided additional incentives. Association of the Roman remains with resurgent Welsh lordship appears to have created a political reason for removal of the structure. Excavations in the Legionary Fortress Museum Garden in Caerleon, directed by David Zienkiewicz in 1992, confirmed the existence of a tetrapylon, a four-way triumphal arch, at the centre of the fortress at Isca (Zienkiewicz 1993, 140). The substantial masonry structure straddled the junction of the via principalis and the via praetoria, providing an imposing approach to the headquarters building (Figure 1). There are a number of precedents for such buildings including surviving structures like the arch of Septimus Severus at Leptis Magna in Libya (see Raven 1969, 84). The Caerleon tetrapylon would have provided an imposing central focus for the fortress of Isca — as well, no doubt, as making an explicit statement of political intent in the aftermath of the protracted guerrilla war with the Silures. A particularly interesting aspect of the tetrapylon is the archaeological evidence for its considerable longevity. -

Monmouthshire Sunday Rota Service 18:00 to 20:00 April 2021 – March 2022 ` Sunday Pharmacy Telephone

Aneurin Bevan University Health Board – Community Pharmacy Out of Hours Monmouthshire Sunday Rota Service 18:00 to 20:00 April 2021 – March 2022 ` Sunday Pharmacy Telephone 4th April 2021* Dudley Taylor Pharmacies Ltd 01291 422041 The Old School House Main Road Portskewett 11th April 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 18th April 2021 D R Rosser Pharmacy 01600 713123 12 Church Street Monmouth 25th April 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 2nd May 2021 Dudley Taylor Pharmacies Ltd 01291 422041 The Old School House Main Road Portskewett 9th May 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 16th May 2021 D R Rosser Pharmacy 01600 713123 12 Church Street Monmouth 23rd May 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 30th May 2021 Dudley Taylor Pharmacies Ltd 01291 422041 The Old School House Main Road Portskewett 6th June 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 13th June 2021 D R Rosser Pharmacy 01600 713123 12 Church Street Monmouth 20th June 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 27th June 2021 Dudley Taylor Pharmacies Ltd 01291 422041 The Old School House Main Road Portskewett 4th July 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 *denotes Bank Holiday 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 11th July 2021 D R Rosser Pharmacy 01600 713123 12 Church Street Monmouth 18th July 2021 H Shackleton Ltd 01873 854310 33 Brecon Road Abergavenny 25th July 2021 Dudley Taylor Pharmacies Ltd 01291 422041 The Old School House Main Road Portskewett -

Black Rock Road, Portskewett Gwent

Black Rock Road, Portskewett Gwent Written Scheme of Investigation for Historic Building Recording and Archaeological Watching Brief Accession Number: TBC Document Ref.: 207290.1 May 2018 © Wessex Archaeology Ltd 2018, all rights reserved Unit 9 Filwood Green Business Park 1 Filwood Park Lane Bristol BS4 1ET www.wessexarch.co.uk Wessex Archaeology Ltd is a company limited by guarantee registered in England, company number 1712772. It is also a Charity registered in England and Wales number 287786, and in Scotland, Scottish Charity number SC042630. Our registered office is at Portway House, Old Sarum Park, Salisbury, Wiltshire, SP4 6EB Disclaimer The material contained in this report was designed as an integral part of a report to an individual client and was prepared solely for the benefit of that client. The material contained in this report does not necessarily stand on its own and is not intended to nor should it be relied upon by any third party. To the fullest extent permitted by law Wessex Archaeology will not be liable by reason of breach of contract negligence or otherwise for any loss or damage (whether direct indirect or consequential) occasioned to any person acting or omitting to act or refraining from acting in reliance upon the material contained in this report arising from or connected with any error or omission in the material contained in the report. Loss or damage as referred to above shall be deemed to include, but is not limited to, any loss of profits or anticipated profits damage to reputation or goodwill loss of -

Sudbrook Portskewett Trails Through the Ages

SUDBROOK A PORTSKEWETT TRAILS THROUGH THE AGES LLWYBRAU TRWY’R OESOEDD Essential Information: The Countryside Code: Respect - Protect - Enjoy SUDBROOK & For local visitor information and details of accommodation call • Be Safe - plan ahead and follow any signs PORTSKEWETT Chepstow Tourist Information Centre on 01291 623772 or see: • Leave gates and property as you find them • Protect plants and animals, and take your litter home www.visitwyevalley.com • Keep dogs under close control • Consider other people Hunger marchers at the Inside the Mission Hall The Pumping Station www.walescoastpath.gov.uk Severn Tunnel in 1936 www.walksinchepstow.co.uk This leaflet has been funded by adventa, Monmouthshire’s Rural www.caldicotcastle.co.uk Development Programme funded by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, the Welsh Assembly Government and Monmouthshire Sudbrook History Exhibition Local transport County Council. For more information visit www.adventa.org.uk. …at the Sudbrook Non Political Club The number 63 bus runs from the village to Caldicot, Severn Tunnel Junction Station and Newport. For details of public transport visit: Credits: Run by volunteers from Caldicot and District Local History Society, A walk through history around the www.traveline-cymru.info Images reproduced with the permission of: you will find a wealth of local information here, including an exhibition villages of Sudbrook and Portskewett Visit Wales © Crown copyright (2013) Nanette Hepburn, Monmouthshire of old photographs and a video about the area. Visitors can use the Parking County Council, Black Rock Lave Net Fishermen. resources to find out more about the Severn Railway Tunnel project, There is car parking at Black Rock Picnic Site and limited street-side Sudbrook History Society, Newport Museum and Art Gallery, Ironbridge Gorge the village of Sudbrook, the lave net fishermen car parking in Portskewett and at Sudbrook near to the Sudbrook Museums Trust, Time Team, David Morgan Photography, Private collections, of Black Rock, and much, much more. -

DIOCESAN PRAYER CYCLE – September 2020

DIOCESAN PRAYER CYCLE – September 2020 The Bishop’s Office Diocesan Chancellor – Bishop Bishop Cherry Mark Powell 01 Bishop’s P.A. Vicki Stevens Diocesan Registrar – Tim Russen Cathedral Chapter 02 Newport Cathedral Canons and Honorary Jonathan Williams Canons The Archdeaconry of Archdeacons - Area Deans – Monmouth Ambrose Mason Jeremy Harris, Kevin Hasler, Julian Gray 03 The Archdeaconry of Newport Jonathan Williams John Connell, Justin Groves The Archdeaconry of the Gwent Sue Pinnington Mark Owen Valleys Abergavenny Ministry Area Abergavenny, Llanwenarth Citra, Julian Gray, Gaynor Burrett, Llantilio Pertholey with Bettws, Heidi Prince, John Llanddewi Skirrid, Govilon, Humphries, Jeff Pearse, John Llanfoist, Llanelen Hughes, Derek Young, Llantilio Pertholey CiW Llanfihangel Crucorney, Michael Smith, Peter Cobb, Primary School 04 Cwmyoy, Llanthony, Llantilio Lorraine Cavanagh, Andrew Crossenny, Penrhos, Dawson, Jean Prosser, Llanvetherine, Llanvapley, Andrew Harter Director of Ministry – Llandewi Rhydderch, Ambrose Mason Llangattock-juxta-Usk, LLMs: Gaynor Parfitt, Gillian Llansantffraed, Grosmont, Wright, Clifford Jayne, Sandy Skenfrith, Llanfair, Llangattock Ireson, William Brimecombe Lingoed Bassaleg Ministry Area Christopher Stone 05 Director of Mission – Anne Golledge Bassaleg, Rogerstone, High Cross Sue Pinnington Bedwas with Machen Ministry Dean Aaron Roberts, Richard Area Mulcahy, Arthur Parkes 06 Diocesan Secretary – Bedwas, Machen, Rudry, Isabel Thompson LLM: Gay Hollywell Michaelston-y- Fedw Blaenavon Ministry Area Blaenavon -

TRADES. [Monmoljthsbirl!

274 CAR TRADES. [MONMOlJTHSBIRl!:. CA·ltPENTEIRS & JOINERS. Richards Thomas & Geor..,e, Shire Uphill Wait. 49 Constance st. Newprt Arthur William, Snatehwood, Abersy- :Newton, Chepstow "' Watkins Edgar George, Llantilio chan, Pontypool Richard'! Alfred, 17 Dany Graig :rd. Pertholey, Abergavenny B:1nfield H. E. Merchant st. Newport Pontymister, Newport [6ar Full liata of thia trade in Baulch H. 16 High st.Caerleon,Newpt Roberts John, Llangibby, Newport United Kingdom, aee Leather Bennett John W. 1 Lower Waun st. 3immons George William, Monmout}l Trade& DirectoryL Price 25a.J & Cwmavon rd. Blaenavon, Pontypl road, Abergavenny Bowen David William, 53 York ter- 3mith Frederick, Undy, Newport race, Georgetown, Tredegar Snell S. T. 70 Caerleon rd. Newport CARRIERS. Brewer Henry Gould, IQ Norman st. Spencer By. 10 Glendower st. Monmth bb J & S St t'100 rd Ch 8 t Caerleon, Newport Stockham F. B. Maryport st. Usk 0 0 .s · Wons. 4 ~ · P w fh Alb t Th v·n Ll Mormh By. 29 Mill st. Newport Butcher .A.rthur Frank, 39 Stafford ~mbbas N er 't e I age, an- Pickfords Ltd. 3 Rodney :rd. Newport road, Maindee, Newport gi y, ewpor ~ Smith R. T. & Co. Glendower street Charles W. E. Richmond road, Pont- Thomas F.van, Llanwern, Newport & Railway station, Monmouth newydd, Newport Thompson J. & Son, Caerleon,Newport Sutton & Co. (John Mattock, agent)~ Clemes Alfred W. xo North st.Newport Turner R. Gt. Oak,. Bryngwyn,Raglan 1 St. Vincent road, Newport Coakham Geo. I Manley rd. Newport Waiters By. 27 Nevlll st.Abergavenny Wynn Robt. & Sons, .'io Shaftesbury st. Crook Thomas, Portskewett,Chepstow Walt~n Arthur, 15 Annesley road, Newport. -

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Week 06/09/2014 to 12/09/2014 Print Date 15/09/2014 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Caerwent DC/2014/01048 Extension to provide sun room Planning Permission Rock Cottage Mr D Knight Mr Chris McGonagle Caerwent Rock Cottage Liddell & Associates Caldicot Caerwent Stuart House NP26 5BB Caldicot The Back NP26 5BB Chepstow Monmouthshire NP16 5HH Caerwent 11 September 2014 347,577 / 189,555 Caerwent 1 Print Date 15/09/2014 MCC Pre Check of Registered Applications 06/09/2014 to 12/09/2014 Page 2 of 14 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Caldicot Castle DC/2013/00796 Erection of 16 no. dwellings with associated parking, access, landscaping and engineering Planning Permission works. Land at White Hart Inn Mr Chris Worthy Mr Cai Parry Sandy Lane Worthy Developments Barton Willmore Caldicot Millenium House Greyfriars House NP26 4NA Severn Link Distribution Centre Greyfriars Road Chepstow Cardiff NP16 6UN CF10 3AL Caldicot 28 August 2014 348,066 / 188,418 DC/2014/00993 Extension of existing roof terrace area by bringing forward existing archways. (utility room and Planning Permission shower room at rear of property do not require planning permission) 82 Castle Lea Mrs Cheyrl Kerr Caldicot 82 Castle Lea NP26 4PJ Caldicot NP26 4PJ Caldicot 28 August 2014 348,227 / 188,376 DC/2014/01050 Rear dormer to loft conversion Certificate of Existing Lawful Use or Developme 6 Churchfield Avenue David Holloway Maison Design Caldicot 6 Churchfield Avenue 25 Caldicot Road NP26 4ND Caldicot Rogiet NP26 4ND Caldicot NP26 3SE Caldicot 09 September 2014 347,886 / 188,544 DC/2014/00706 Front and rear projecting gable extensions to form a second floor. -

Cyngor Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol

Cyngor Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol Ceisiadau Cynllunio a Gofrestrwyd / Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Wythnos / Week 08.10.20 i/to 14.10.20 Dyddiad Argraffu / Print Date 15.10.2020 Mae’r Cyngor yn croesawu gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg, Saesneg neu yn y ddwy iaith. Byddwn yn cyfathrebu â chi yn ôl eich dewis. Ni fydd gohebu yn Gymraeg yn arwain at oedi. The Council welcomes correspondence in English or Welsh or both, and will respond to you according to your preference. Corresponding in Welsh will not lead to delay. Ward/ Ward Rhif Cais/ Disgrifia d o'r Cyfeiriad Safle/ Enw a Chyfeiriad yr Enw a Chyfeiriad Math Cais/ Dwyrain/ Application Datblygiad/ Site Address Ymgeisydd/ yr Asiant/ Application Gogledd Number Development Applicant Name & Agent Name & Type Easting/ Description Address Address Northing Crucorney DM/2020/01261 The variation of Campston Mill Mr Stephen Leonard Mr Andrew Mod or 335760 condition 2 of Barry-cathlea Road The Poplars, Venables Removal of 221175 Plwyf/ Parish: Dyddiad App. Dilys/ planning consent Llanvihangel Grosmont Avarchitecture Condition Grosmont Date App. Valid: DM/2018/01956, to Crucorney Nr Abergavenny 17 Pentaloe Close 28.09.2020 Community include the revised Monmouthshire Grosmont Mordiford Council set of drawings that NP7 8EF NP7 8ET Herefordshire shows windows United Kingdom HR1 4LS added to ground floor Crucorney DM/2020/01351 We are proposing Middle Cottage Mr Martin Jones No Agent Householder 338115 to create a 2 Steppes Farm Middle Cottage 221962 Plwyf/ Parish: Dyddiad App. Dilys/ driveway off new New Line Road 2 Steppes Farm Grosmont Date App. -

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Week 14/03/2015 to 20/03/2015 Print Date 25/03/2015 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Croesonen DC/2015/00299 Discharge of conditions 1,2,3,4,5, from previous application DC/2011/01228. Discharge of Condition Former garages site Monmouthshire Housing Association Hammond Architectural Ltd Llwynu Lane/St Davids Road Nant y Pia House Melrose Court Mardy Mamhilad Technology Park Melrose Hall Abergavenny Mamhilad Cypress Drive NP7 6BE Monouthshire St Mellons NP4 OJJ Cardiff CF3 OEG Llantilio Pertholey 16 March 2015 330,291 / 215,583 Croesonen 1 Devauden DC/2015/00297 Proposed rear extension Planning Permission 14 Churchfields Mr Robert Oglesby Mr Mark Webster Devauden 14 Churchfields The Basin at Tregagle Chepstow Devauden Nr Monmouth NP16 6NB Chepstow NP25 4RX NP16 6NB Devauden 11 March 2015 348,285 / 199,117 DC/2015/00275 Erection of four timber stables with tack, bedding and feed storage. Planning Permission Change of Use from agricultural to Equestrian. The Old Rectory Mr Charles Newington-Bridges Kingsland Sawmills Ltd Wolvesnewton The Old Rectory Kingsland Chepstow Wolves Newton Leominster NP16 6NY Chepstow Herefordshire NP16 6NY HR6 9SF Devauden 10 March 2015 345,453 / 199,722 Devauden 2 Print Date 25/03/2015 MCC Pre Check of Registered Applications 14/03/2015 to 20/03/2015 Page 2 of 16 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Dixton With Osbaston DC/2015/00306 Non material amendment (extend length in height of the stairwell window on south elevation) Non Material Amendment in relation to planning permission DC/2009/00001.