An Interview with Iota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The True Measure of Success Why David Howe Puts Honesty and Integrity First

JOURNALREAL ESTATE INSTITUTE OF NEW SOUTH WALES | SEP/OCT 2017 VOL 68/05 The true measure of success Why David Howe puts honesty and integrity first PROFESSIONALISM CELEBRATING EXCELLENCE HANDLING A HACK Examining our professional identity Awards for Excellence finalists revealed Be alert and alarmed about cyber crime INSIDE REAL ESTATE JOURNAL The Real Estate Journal is the official magazine of the Real Estate Institute of New South Wales. CONTENTS 30 To terminate or not 30-32 Wentworth Avenue UPFRONT to terminate? Sydney NSW 2000 5 A word from the President (02) 9264 2343 The NSW Small Business [email protected] 6 In brief Commissioner explains the www.reinsw.com.au complexities of managing 8 AGM notice Managing Editor a mixed-use tenancy. Cath Dickinson 8 Board of Directors’ Wordcraft Media election notice 32 Handling a hack: Be alert 0410 330 903 … and alarmed! [email protected] 9 Chapter Committees www.wordcraftmedia.com.au What you can do to minimise nomination notice the risk of your agency falling Advertising (02) 9264 2343 9 Division Committees victim to a cyber attack. [email protected] nomination notice 35 Cyber insurance 10 REINSW Professionalism Art Direction and Design Cyber risk is a major emerging Bird Project Think Tank 0414 332 146 risk for all agencies. Are you [email protected] covered? www.birdproject.com PERSPECTIVES 14 Braving the big chill Printing The annual Real Estate CMMA Digital and Print TRAINING AND www.cmma.com.au Sleep Out saw 180 agents EVENTS raise more than $277,000 36 Novice Auctioneers Photography for charity. -

The Screaming Jets Chrome Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Screaming Jets Chrome mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Chrome Country: Australia Released: 2016 Style: Hard Rock, Pub Rock, Rock & Roll MP3 version RAR size: 1474 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1847 mb WMA version RAR size: 1813 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 792 Other Formats: DXD MOD WAV MIDI ASF ADX VOC Tracklist Hide Credits Automatic Cowboy 1 3:27 Written-By – Woseen* Cash In Your Ticket 2 4:10 Written-By – Woseen* Razor 3 3:17 Written-By – Gleeson*, Hocking* No Place No Home 4 4:36 Written-By – Woseen*, Kingman* The Grip 5 2:40 Written-By – Woseen*, Kingman* Sex And Violence 6 4:27 Written-By – Woseen* Won't Stop You 7 3:15 Written-By – Woseen* Smack In The Mouth 8 3:38 Written-By – Gleeson*, Hocking*, Woseen* Scar 9 3:58 Written-By – Woseen* Turn It Around 10 3:09 Written-By – Woseen* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Yabbie Road Studio Recorded At – Studios 301, Byron Bay Overdubbed At – Phat Majik Entertainment Mixed At – Phat Majik Entertainment Credits Artwork – John E. Engelhardt Bass, Backing Vocals – Paul Woseen Drums – Mickl Sayers Engineer – Scott Kingman (tracks: 1, 2, 4-7, 9, 10) Engineer [Assistant] – Don Frizza (tracks: 1, 2, 4-7, 9, 10), Hannah MacNamara (tracks: 1, 2, 4-7, 9, 10) Guitar – Scott Kingman Guitar, Backing Vocals – Jimi "The Human" Hocking* Lead Vocals – Dave Gleeson Mastered By – Matthew Gray Photography By – Scott Kingman Producer – The Screaming Jets (tracks: 3, 8) Producer, Recorded By, Engineer, Mixed By – Steve James (tracks: 1, 2, 4-7, 9, 10) Recorded By – Scott Kingman (tracks: 3,8) Related Music albums to Chrome by The Screaming Jets 1. -

International Journal of Music Business Research, October 2013, Vol

36 International Journal of Music Business Research, October 2013, vol. 2 no. 2 The Newcastle music industry: An ethnographic study of a regional creative system in action Phillip McIntyre and Gaye Sheather1 Abstract This paper presents detailed preliminary findings from an ethnographic study of the Newcastle NSW music industry. It argues that in the midst of seemingly continuous change primarily wrought by the advent of new global trade regimes and associat- ed digital technologies there are also fundamental continuities at work for local music industries. These continuities are evident in the idea that these industries are part of a dynamic system of choice-making agents constituted by musicians, pro- moters, media operatives, venue owners, educators, policy makers and many oth- ers. They compete and collaborate within the structures of a gift and financial economy which exists in a regional and global framework with a dynamic history that has helped shape this creative system in action. Keywords: Creative system, creativity, music industry, field, ethnography 1 Introduction Prior to the turn of the millenium "fundamental ideological changes in the global political arena led to the creation of pro-market international trade regimes" (Thussu 2000: 82). As the processes of deregulation, pri- vatization and the opening of borders to rapid flows of capital "com- bined with new digital information and communication technologies" (ibid.) the impacts these produced have been felt across all economies internationally, from advanced to less well developed ones. This certain- ly happened in Europe and America but other regions, countries and localities have been living through the continuities and changes these developments continue to bring. -

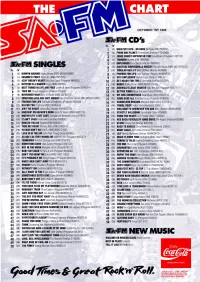

SA-FM Charts, 1992-10-01 to 1992-11-12

OCTOBER 1ST 1992 Na. LW 1 (3) GREATEST HITS - DR HOOK Dr Hook (EMI 7995052) 2 (2) FORM ONE PLANET Rockmelons (Festival TVD93360) 3 (11 JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR 1992 Soundtrack (Polygram 5137132) 4 (6) TOURISM Roxette (EMI 7999294) 5 117) UNPLUGGED Eric Clapton (Warner 9362450) 6 (5) ELECTRIC SOUP/GORILLA BISCUIT Hoodoo Gurus (BMG 432110740-2) NO. LW 7 (14) TUBULAR BELLS II Mike Oldtield (Warner 4509906) 1 (2) HUMPIN AROUND Bobby Brown (BMG MCAD518962) 8 (4) FRIENDS FOR LIFE Jose Carieras (Warner 4509902552) 2 (1) SESAME'S TREET Smart Es (BMG PDS 510) 9 (9) MTV UNPLUGGED Mariah Carey (Sony 471869 2) 3 (7) ACHY BREAKY HEART Billy Ray Cyrus (Polygram 8640562) 10 (7) GET READY FOR THIS 2 Unlimited (Festival D 30797) 4 (4) RHYTHM IS A DANCER Snap (BMG 665309) 11 (10) BOBBY Bobby Brown (BMG MCAD 10417) 5 (3) BEST THINGS IN LIFE ARE FREE Luther & Janet (Polygram 587410-4) 12 120) AMERICA'S LEAST WANTED Ugly Kid Joe (Polygram 512571-) 6 (9) TAKE ME Dream Frequency (Festival D11203) 13 (18) BETTER TIMES Black Sorrows (Sony 4721492) 7 (8) NOVEMBER RAIN Guns N' Roses (BMG GEFDS 21) 14 (8) MY GIRL SOUNDTRACK Soundtrack (Sony 469213-2) 8 (15) SOMETIMES LOVE JUST AIN'T ENOUGH Patty Smyth/Don Henley (BMG MCADS 54403) 15 (271 SOME GAVE ALL Billy Ray Cyrus (Polygram 5106352) 9 (5) FRIENDS FOR LIFE Carreras & Brightman (Polygram 863308) 16 124) CHAMELEON DREAMS Margaret Urlich (Sony 472118.2) 10 (12) DO FOR YOU Euphoria (EMI 8740054-2) 17 119) TRIBAL VOICE Yothu Yindi (Festival D 30602) 11 (21) AIN'T NO DOUBT Jimmy Nail (Warner 4509902272) 18 (11) WELCOME -

The Power of Positive Programs in the American Humane Movement

The Power of Positive Programs in the American Humane Movement discussion papers of the National Leadership Conference of The Humane Society of the United States October 3-5, 1969 Hershey, Pennsylvania ...... �l CONTENTS Foreword .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Report of the President (Mel L. Morse) . .. .. .. 4 Report of the Treasurer (William Kerber) . .. .. .. .. .. 15 Our Challenge and Our Opportunity (Coleman Burke) ......... 18 Protection of Wildlife (Leonard Hall) . .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Problems in Transportation of Animals (Mrs. Alice M. Wagner) ............................... 28 Humane Education Programs for Youth (Dr. Virgil S. Hollis; Sherwood Norman; Dr. Jean McClure Kelty) .............. 34 The Misuse of Animals in the Science Classroom (Prof. Richard K. Morris) ... , . .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 1 Symposium on Livestock Problems (John C. Macfarlane; Dr.F.J.Mulhern) .................................. 58 Extension of Community Programs for Animal Protection (Milton B. Learner) ......................... 68 Protection for Animals in Biomedical Research (F. L. Thomsen) .................................... 75 Cruelty for Fun (Cleveland Amory) ....................... 83 The Humane Movement and the Survival of All Living Things (Roger Caras) ........................ 89 Published by THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES Resolutions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 95 1145 Nineteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FOREWORD The 1969 HSUS National Leadership Conference, held in Hershey, Pa., on October 3-5, was the occasion for a critical evaluation by national leaders of the most important problems currently facing the American humane movement. The three day meeting concentrated on discussion of strategy and program aimed at progress all along the humane front. The great tasks confronting humanitarians were faced with confidence in the movement's ability to tackle them successfully. There were major speeches by recognized experts. There were panel discussions and question and answer sessions. -

Media Release

43 High Street Gawler East PO Box 130 Gawler SA 5118 Tel: 08 8522 9211 Fax: 08 8522 9212 Email: [email protected] MEDIA RELEASE Date: 5 February 2018 Embargo: None Pages: 2 Publication: All The Gawler Fringe Opening Event is back in Walker Place in 2018 The Fringe will again make its mark on Gawler with the Gawler Fringe Opening Event to commence in Walker Place on Friday 16 February at 3pm. The Opening Event will bring a weekend full of free Fringe festivities and will be sure to include something for every member of the family. The theme of this year’s event is Live, Embrace, Enjoy Local and the jam-packed program showcases the amazing talent that Gawler has to offer. Mayor Karen Redman said “The heart of Gawler will be a hive of activity with a range of outstanding local performances and some fantastic feature acts as well”. The Mayor goes on to say “At this year’s event the community can expect to see some well-known local faces with performances from groups and solo artists such as the Gawler Ukes, Burnout, Generation XYZ, The Rickety Chicks, Lily and the Drum, Allan Dean, Liam Halford, Abbie Ferris and Scott Rathman Jnr. There’s also lots of performances by Gawler’s young up and coming talent”. Friday night’s feature act is not to be missed with a dynamic performance by Dave Gleeson; legendary lead vocalist of two of Australia’s most iconic rock bands, ‘The Screaming Jets’ and ‘The Angels’. For this one-off Fringe show, Gleeso will be joined by local Gawler legends Crafty and the Shindiggers. -

Polygram 1983-1992

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS PolyGram 7”, 12” singles & LP’s 1983 to 1992 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, MAY 2019 POLYGRAM 7”, 12” SINGLES & LP’S, 1983–1992 POLYGRAM PRODUCT GUIDE –1 = 12” SINGLES, LP’S –2 = CD SINGLES, CD’S (NOT LISTED) –3 = VHS VIDEO (NOT LISTED) –4 = CASSETTE SINGLES, CASSETTES (NOT LISTED) –7 = 7” SINGLES 370, 377—WINDHAM HILL 370 111-1 TEARS OF JOY TUCK & PATTI 1.90 377 008-1 LOVE WARRIORS TUCK & PATTI 1.90 390–397—A & M 390 419-7 LOVE SCARED / LOVE SCARED PART II (LET’S TALK IT OVER) LANCE ELLINGTON 3.91 390 460-7 STONE COLD SOBER / THE RETURN OF MAGGIE BROWN DEL AMITRI 7.90 390 462-7 THE MESSAGE IS LOVE (2 VERSIONS) ARTHUR BAKER 3.90 390 462-1 THE MESSAGE IS LOVE (2 VERSIONS) / THE MESSAGE IS CLUB ARTHUR BAKER 3.90 390 466-7 DIAMOND IN THE DARK / LAST NIGHT CHRIS DE BURGH 6.90 390 471-7 LOVE TOGETHER (2 VERSIONS) L.A. MIX 7.90 390 471-1 LOVE TOGETHER (2 VERSIONS) L.A. MIX 7.90 390 472-7 PERFECT VIEW / WE NEVER MET THE GRACES 3.90 390 474-7 NOTHING EVER HAPPENS / NO HOLDING ON DEL AMITRI 4.90 390 474-1 NOTHING EVER HAPPENS / NO HOLDING ON / SLOWLY, IT’S COMING BACK DEL AMITRI 5.90 390 475-7 I’M A BELIEVER / NO WAY OUT GIANT 6.90 390 476-7 INSIDE OUT / BACK TO WHERE WE STARTED GUN 4.90 390 477-7 WITH A LITTLE LOVE / WINDOW PEOPLE SAM BROWN 4.90 390 477-1 WITH A LITTLE LOVE / WINDOW PEOPLE / DOLLY MIXTURE SAM BROWN 4.90 390 480-7 A CHANGE IS GONNA COME / MY BLOOD THE NEVILLE BROTHERS 3.90 390 484-1 SUPER LOVER (2 VERSIONS) / WHEN WILL I SEE YOU AGAIN BARRY WHITE 6.90 390 486-7 TWO TO MAKE IT RIGHT -

A Beat for You Pseudo Echo a Day in the Life the Beatles a Girl Like

A Beat For You Pseudo Echo A Day In The Life The Beatles A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins A Good Heart Feargal Sharkey A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bryan Ferry A Kind Of Magic Queen A Little Less Conversation Elvis vs JXL A Little Ray of Sunshine Axiom A Matter of Trust Billy Joel A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Touch Of Paradise John Farnham A Town Called Malice The Jam A View To A Kill Duran Duran A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum Abacab Genesis About A Girl Nirvana Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Absolute Beginners David Bowie Absolutely Fabulous Pet Shop Boys Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Adam's Song Blink 182 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Adventure of a Lifetime Coldplay Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers Affirmation Savage Garden Africa Toto After Midnight Eric Clapton Afterglow INXS Agadoo Black Lace Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) Phil Collins Against The Wind Bob Seger Age of Reason John Farnham Ahead of Myself Jamie Lawson Ain't No Doubt Jimmy Nail Ain't No Mountain High Enough Jimmy Barnes Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine The Rockmelons feat. Deni Hines Alive Pearl Jam Alive And Kicking Simple Minds All About Soul Billy Joel All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All By Myself Eric Carmen All Fired Up Pat Benatar All For Love Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart & Sting All I Do Daryl Braithwaite All I Need Is A Miracle Mike & The Mechanics All I Wanna Do Sheryl Crow All I Wanna Do Is Make Love To You Heart All I Want -

Better Bruno Mars

AC/DC - Highway to hell The Screaming Jets - Better Bruno Mars - Uptown funk Soft Cell - Tainted love Red Hot Chili Peppers - Under the bridge The Stray Cats - Stray Cat Strut Bon Jovi - Someday I’ll be Saturday night Fleetwood Mac - Go Your Own Way Tracy Chapman - give me one reason The Beatles - don’t let me down Cream - sunshine of your love Paul Kelly - dumb things 4 Non Blondes - what’s up Guns N’ Roses - sweet child o’ mine The Animals - house of the rising sun Alanis Morrisette - you outta know Peggy Lee- Fever Nirvana - heart shaped box Nirvana - lithium The Beatles - while my guitar gently weeps Gnarls Barkley - Crazy Johnny Cash - god’s gonna cut them down The Doors - Roadhouse blues John Butler Trio - Zebra Foo Fighters - Times Like These John Farnham - The Voice Creedence Clearwater Revival - Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival - Forunate Son Creedence Clearwater Revival - Bad Boon Rising 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite Dragon - April Sun Rick Springfield - Jessies Girl The Killers - Mr Brightside Kings Of Lean - Sex Is On Fire Noiseworks - Take Me Back Lynard Skynard - Sweet Home Alabama The Choirboys - Run To Paradise Bruno Mars - Locked Out Of Heaven Fleetwood Mac - Dreams The Darkness - Believe In A Thing Called Love Violent Femmes - Blister In The Sun Weetus - Teenage Dirtbag Fuel - Shimmer Jet - Are You Gonna Be My Girl Powderfinger - Baby I Got You On My Mind Amy Winehouse - Rehab The Living End - All Torn Down Steely Dan - Stuck In The Middle With You Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses Elvis Presely - Hound Dog Stevie Wonder -

Creativity & Cultural Production in the Hunter

An applied ethnographic study of Creativity & Cultural new entrepreneurial systems in the Production in the Hunter creative industries. Newcastle The University of Newcastle I April 2019, ARC Grant LP 130100348 Now AuslnilianGon ,rnment ���;�Busmess nt Ai&i1rall1.11Rtu1n:bCou11dl 6. MUSIC 6.1 Introduction This part of the report outlines the history, structure, business models, operational methods and important personnel associated with each sector. This section outlines the music industry in Australia (Cunningham & Turnbull 2014) before looking specifically at the music industry in the Hunter region. It locates the current Hunter Region music scene within Australian music history particularly in relation to the European tradition, specifically the American and British music traditions. Of note is the fact that the ongoing digital revolution continues to reshape the industry, its composition, songwriting, recording, performance and business modes. Structurally the music industry is comprised of three major and related sectors i.e. publishing, recording and live performance. There are ancillary sectors as well such as manufacturing, retail and media which are interconnected with the three major sectors. There are various business models used within these sectors. The operational methods are both formal (e.g. use of contracts, performance schedules etc.) and informal (e.g. adherence to a gift economy). Its most important personnel include songwriters, composers, musicians, managers, touring crews, venue operators, agents, promoters, producers, engineers, publishers, A&R operatives and, of course, the audience. 6.2 A Brief History of the Music Industry in Australia. The music industry in the Hunter is a local variant of a much larger national and global one (Miller & Shahriari 2012). -

Whiter Rock: Why the Easybeats Didn't Suceed In

Oz Rock and the ballad tradition in Australian popular music ‘While we are sitting here, singing folksongs, in our folksong clubs, the folk are somewhere else, singing something different.’ Quoted in Jeff Corfield ‘The Australian Style’1 Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, and the Twilights, discussed in chapter one, were manifestations of an Australian popular music sensibility which was fundamentally European-derived, white. It was a tradition that valued melody, musical linearity and lyrical clarity. These bands, in particular Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, and the Easybeats, laid the basis for the flowering of Australian rock in the 1970s and for Oz Rock groups such as Rose Tattoo, the Angels, Midnight Oil, Cold Chisel, Australian Crawl, and, in the 2000s, You Am I and Powderfinger among others.2 This tradition has continued to blend melody with strong guitar riffs and a big beat. Billy Thorpe’s self-penned ‘Most People I Know (Think That I’m Crazy)’, released in 1972, with its melody, driving beat and anthemic chorus combined with an emphasis on the lyrics, provided a template for Australian rock, for a tradition of bands—those Oz Rock bands that I mentioned above—whose success in Australia has, in the main, continued to be far greater than what they have achieved overseas.3 This tradition continues to privilege elements drawn from the white, European musical tradition over influences from African-American, and other Black musics. This hard rock development in Australia has another strand, the importance of the traditional ballad tradition and, along with this, the influence of American country music. -

Song List 2016

Dylan-Song List 2016 Song title Artist Song title Artist Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Condition Kenny Rogers Semi Charmed Life 3rd Eye Blind Blue on Black Kenny Wayne Sheapard Take Me To The River Al Green Fly Away Lenny Kravitz Let's stay together Al Green Dance me to the end of Love Leonard Cohen Amazing Alex Lloyd Even when I'm sleeping Leonardo's Bride Green Alex Lloyd Hanging By A Moment Lifehouse I need a dollar Aloe Blacc Hakuna Matata Lion King Lovesong Amiel Stay Lisa Loeb and Nine Stories Valerie Amy Winehouse I alone Live I’m Outta Love Anastacia Lightning Crashes Live Big Jet Plane Angus and Julia Stone Selling the Drama Live Paper Aeroplane Angus and Julia Stone All Torn Down Living End Fuel Ani Defranco Walk on the Wild Side Lou Reed Angry anymore Ani Defranco California Dreaming Mamas and the Papas Ticket to Ride Beatles King of the Bongo Manu Chao Hide your love away Beatles Heard it through the Grapevine Marvin Gaye Iko Iko Belle Stars Hang Matchbox 20 Steal My Kisses Ben Harper Push Matchbox 20 Excuse me Mister Ben Harper 3AM Matchbox 20 Burn one Down Ben Harper Down Under Men at Work Sexual Healing Ben Harper Nothing Else Matters Metallica Drugs Don’t Work Ben Harper Stay Human Michael Franti Diamonds on the inside Ben Harper Hole in the Bucket Michael Franti and Spearhead Stand By Me Ben King Beds are Burning Midnight Oil Aint no Sunshine Bill Withers The Dead Heart Midnight Oil All the Small things Blink 182 Scar Missy Higgins Fire, water, burn Bloodhound Gang Float on Modest Mouse Blowin in the wind Bob Dylan To Be With