Surviving the Dark Ages 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTIS—NAPLES ANNOUNCES OFFICIAL SELECTIONS for the 2020 NAPLES INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL (October 22-25)

Home of The Baker Museum and the Naples Philharmonic Contact: John Wildman, Wildworks PR [email protected] | 323-600-3165 Therese McDevitt, Communications Director [email protected] | 239-254-2794 Website: artisnaples.org Facebook: facebook.com/artisnaples Twitter: @artisnaples | Instagram: artisnaples ARTIS—NAPLES ANNOUNCES OFFICIAL SELECTIONS FOR THE 2020 NAPLES INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL (October 22-25) SPECIAL OUTDOOR SCREENINGS WILL FEATURE ALICE GU’S AWARD- WINNING THE DONUT KING AS THE OPENING NIGHT SELECTION, WITH AURÉLIA ROUVIER AND SEAMUS HALEY’S FESTIVAL FAVORITE BANKSY MOST WANTED THE CLOSING NIGHT FILM The Donut King, Banksy Most Wanted Naples, FL (September 30, 2020) – Artis—Naples announced today the complete program lineup for the 12th Annual Naples International Film Festival (NIFF) to be held October 22-25, 2020 featuring both virtual and in-person events. NIFF’s in-person screenings will include two documentaries, opening on October 22 with Alice Gu’s award-winning documentary The Donut King, and closing on October 25 with Aurélia Rouvier and Seamus Haley’s festival favorite Banksy Most Wanted. Both screenings will be outdoors on a large screen in the Norris Garden on the Artis─Naples Kimberly K. Querrey and Louis A. Simpson Cultural Campus. Both evenings start with a red carpet arrival at 7pm followed by the film screening at 7:30pm. In addition to the opening and closing nights, two other in-person screenings will take place in Norris Garden: a NIFF Shorts Showcase of exciting selections from this year’s shorts programs will screen on Friday, October 23 and Casimir Nozkowski’s romantic dramedy The Outside Story, starring Star Trek: Discovery’s Sonequa Martin-Green screens on Saturday, October 24, both at 7:30PM. -

Janice Mason Art Museum LESSON PLANS for WIER EXHIBIT Background Information

Janice Mason Art Museum LESSON PLANS FOR WIER EXHIBIT Background Information ARTIST NAME : Richard Estes ART PIECE ON DISPLAY: “Untitled (Chinese Lady)” About the Artist Richard Estes was born on May 14, 1936, in Kewanee, Illinois, but his family actually lived in Sheffield, a very small town 20 miles from his birthplace. He always liked to draw and still has a drawing he did when he was about four years old and signed it “Dick Estes”. When he was eight years old, he received an oil painting set for Christmas. His family moved to Chicago when Estes was a teenager, and he studied at the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1950’s, where his training centered on figure drawing and traditional academic painting. Estes said, “ I never really thought I’d wind up as a painter, rather, I thought I would probably do commercial art or design or something like that. I didn’t think I’d be successful as a painter although I always wanted to do it.” After graduation from the Art Institute, Estes moved to New York, working in the graphic design field as a freelance illustrator and for various magazine publishers and advertising agencies. He continued to paint at night, and his first one-person show opened in New York in 1968. Most of Estes’s paintings from the early 1960’s are scenes of New Yorkers engaged in urban activities. Around 1967 his paintings of city street scenes changed to images of glass storefronts, reflecting distorted images of buildings and cars. The artist works from photographs to create his free-hand paintings. -

0584 03 AB CAM 16P IDI.Indd

3 Trailblazing Learning Activities Activity 1 The object of this theme is to explore the relationship between paths and the marks left on them. Create a long path on the fl oor with continuous paper and leave your mark on it using methods such as Pollock’s drip technique. That way, your gestures and body movements will become creative materials just like the paint. Use liquid tempera for this task. Like Pollock, you might also fi nd it helpful to use sticks and other objects to spread the paint. Willem de Kooning Red Man with Moustache, 1971 Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid Activity 2 Activity 3 In the second half of the 20th century, some artists returned to Use this work to examine the contributions to painting the path of reality and fi gurative representation. Hyperrealism that Edgar Degas made. Think about the theme of this or photorealism gave rise to works that looked very much like work and fi nd out what other themes this painter was photographic reproductions, in which the artist adopted a interested in. mechanical gaze, becoming a fi xed, unmoving eye. Their images often showed the city as a cold, empty environment, uninhabited Degas was interested in photography: try to discover how or with just a few isolated fi gures. this technique might have infl uenced his painting. Where do you think the painter is observing this scene from? Working with a digital camera, choose a theme and make a digital photo album. For example, you might want to explore aspects of your school, your surroundings or your neighbourhood. -

A Finding Aid to the Ivan C. Karp Papers and OK Harris Works of Art Gallery Records, 1960-2014, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ivan C. Karp Papers and OK Harris Works of Art Gallery Records, 1960-2014, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines and Joy Goodwin 2014 October 17 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1960-2013.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Administrative Files, 1969-2014................................................................ 9 Series 3: Exhibition Files, 1969-2014................................................................... -

The Photograph and Superrealism·

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1982 The hotP ograph and Superrealism Christopher Stokes Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Art at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Stokes, Christopher, "The hotP ograph and Superrealism" (1982). Masters Theses. 2900. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2900 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT� Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings� Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission· be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I r.espectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because �- -�� Date Author m THE PHOTOGRAPH AND SUPERREALISM· (TITLE) BY ClffiISTOPHER STOKES r•' ,,.. THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ART IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1982 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE DATE I ·, AOMMITTEE MENfBER "tOMMITTEE MEMRFR � u- DEPARTMEN AIRPERSON THE PHOTOGRAPH AND SUPERREALISM By Christopher Stokes B.A. -

Denton, Texas December 1982

AN INVESTIGATIVE STUDY OF PAINTINGS CONTAINING TRANSPARENT~LASSWARE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE . TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS By BETTY BEAVER CAN~NELL, B.~.A. IN ART DENTON, TEXAS DECEMBER 1982 {hfSI~ ,r,qq2 ('. J_ TABLE OF CONTENTS> Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iv. Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 6 III. HISTORICAL REVIEW OF STILL LIFE'PAINTING 18 IV. ROMAN PERIOD . 22 v. ITALIAN CARAVAGGIO. 2 8 VI. SPANISH VELAZQUEZ . ., . ·.• . 35 VII. DUTCH -- HEDA, CLAESZ AND REMBRANDT .. 44. VI I I . FRENCH -- STOSKOPFF, CHARD IN AND.~ MANE~ ;. 58 · IX. AMERICAN -- FISH AND ESTES . 71 X. STATEMENT BY THE AUTHOR . 95 XI. SUMMARY. ":. .) . ~· 98 REFERENCE LIST. 101 iii. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ~ J ";· Figure . Page 1. ROMAN. "PEACHES AND GLASS JAR" • • 27 2. ROMAN. DETAIL OF. STILL LIFE WITH fRUIT • 27 ~ t J: '' ~ '. 3. CARAVAGGIO. "THE SUPPER AT EMMAUS" • • 33 4. CARAVAGGIO. STILL LIFE 33 5. CARAVAGGIO. DETAIJ,J OF "BOY BITTEN BY A LIZARD" •., 34 . ~ 6. •· .. .. • \; 34 CARAVAGGIO. "BACCHUS" ·," . ~ .. ) . \ 7. VELAZQUEZ. "THE WATER SELLER OF SEVILLE" 4 2 ..' 8. VELAZQUEZ. DETAIL OF "WATER SELLER OF SEVILLE" • 42 9. VELAZQUEZ. DETAIL OF "OLD WOftTAN COOKING EGGS" . • 4 3 10. PIETER CLAESZ. STILL LIFE WITH SHORT ROEMER 55 AND PASSGLAS 11. PIETER CLAESZ. STILL LIFE WITH SHORT ROEMER 55 AND FLAGON 12. WILLEM CLAESZ HEDA. STILL LIFE WITH ELONGATED .• 56 ROEMER 13. WILLEM CLAESZ HEDA. STILL LIFE WITH ELONGATED· • 56 ROEMER AND FLUTE GLASS 14. REMBRANDT. "SELF PORTRAIT WITH SASKIA" • • 57 15. -

ART 2316 – Intro to Painting Sp 2021

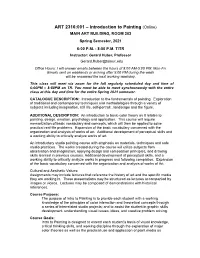

ART 2316:001 – Introduction to Painting (Online) MAIN ART BUILDING, ROOM 202 Spring Semester, 2021 6:00 P.M. - 8:50 P.M. T/TR Instructor: Gerard Huber, Professor [email protected] Office Hours: I will answer emails between the hours of 8:00 AM-5:00 PM, Mon-Fri. Emails sent on weekends or arriving after 5:00 PM during the week will be answered the next working weekday. This class will meet via zoom for the full regularly scheduled day and time of 6:00PM – 8:50PM on TR. You must Be aBle to meet synchronously with the entire class at this day and time for the entire Spring 2021 semester. CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION: Introduction to the fundamentals of painting. Exploration of traditional and contemporary techniques and methodologies through a variety of subjects including imagination, still life, self-portrait , landscape and the figure. ADDITIONAL DESCRIPTION: An introduction to basic color theory as it relates to painting, design, emotion, psychology and application. This course will require memorization of basic vocabulary and concepts, which will then be applied to solve practical real-life problems. Expansion of the basic vocabulary concerned with the organization and analysis of works of art. Additional development of perceptual skills and a working ability to critically analyze works of art. An introductory studio painting course with emphasis on materials, techniques and safe studio practices. The works created during the course will utilize subjects from observation and imagination, applying design and composition principles, and drawing skills learned in previous courses. Additional development of perceptual skills, and a working ability to critically analyze works in progress and following completion. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Anthony Brunelli: in Retrospect

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Anthony Brunelli: In Retrospect New York, NY—The Louis K. Meisel Gallery is pleased to announce Anthony Brunelli: In Retrospect—a survey of Brunelli’s 25 years as a Photorealist painter. Featuring paintings from his earliest cityscapes of his hometown of Binghamton, NY to his latest paintings of Asia, Europe and the White Mountains of New Hampshire, this exhibition shows the transitions that Brunelli’s work has taken over the trajectory of his career. Emerging from a new generation of Photorealists, Anthony Brunelli is a champion of the movement. He has spent his career experimenting with new subject matter, compositions and techniques in order to bring a fresh perspective to Photorealism and to his favorite subject— cityscapes. Influenced by Richard Estes and Edward Hopper, Brunelli’s earliest large-scale paintings depict the forgotten mill towns of Upstate New York in the 1990s. These works not only featured new subject matter for Photorealism, but also introduced a new compositional format; the canvases themselves were narrow and extraordinarily horizontal. Brunelli introduced the first extreme panoramas in Photorealism. As he has matured, Brunelli’s subject matter and compositions have expanded beyond his earliest years. His painting style has tightened, becoming more detailed, and his compositions have more depth and motion. In the late 1990s, Brunelli became the first Photorealist to depict scenes of Southeast Asia; in these paintings, he slowly introduced figures into the foreground of his paintings, thereby providing the audience with a figurative narrative that diverges from the stillness embodied in his early works. His latest paintings of Europe, Asia and the regional areas of the United States have continued to build on these progressions, with Brunelli becoming ever-more technically proficient and compositionally aware. -

Idelle Weber 1932 – 2020

IDELLE WEBER 1932 – 2020 It is with great sadness that Hollis Taggart announces the death of Pop-art icon Idelle Weber. Weber passed away on March 23 at the age of 88. Over the course of her multi-decade career, Weber produced an impressive oeuvre that drew on and expanded the visual vocabularies of the Pop-art and Photorealist movements. From her early silhouette works of the 1960s and ‘70s, which featured faceless black and white contoured figures in corporate and abstract settings, to her photorealist paintings that captured the detritus of urban life, Weber’s practice poignantly reflected American life and culture. In her works, turbulent political themes, such as the Vietnam War, the Kennedy assassination, consumerism, and environmental decay, were distilled into essential forms. This dynamic interplay between formal and cultural investigation set Weber apart from contemporaries like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, and positioned her as a critical voice in the development of American history and art. Weber’s distinct approach and vision earned her an early place in New York’s male-dominated art circles. She was represented by Bertha Schaefer from 1962-1964 and her work was shown in solo presentations at Bertha Schaefer, Hundred Acres gallery, and OK Harris as well as in important group exhibitions such as Pop Goes the Easel (1963) at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Contemporary Drawings (1964) at the Guggenheim Museum, The New American Realism (1965) at the Worcester Museum of Art, and Pop Art and the American Tradition (1965) at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Today, as the contributions of post-war women artists have begun to be re-examined, Weber’s work has gained renewed recognition. -

New York Artist Richard Estes Turns His Exacting

Isn’t that… stes. e Mirror on ichard r NewMaine York artist Richard Estes turns his exacting style on…us. axi (1999, 36: x 66”, oil on canvas) by by DanIel Kany t Water 4 2 p o r t l a n d monthly magazine lor. f ren o hoto: p . K or y W e n h Gallery, G arlborou m stes, courtesy of e ichard r oundation, 2002.13. © f rosby Kemper c nid and e issouri, Gift of the m ity, c rt, Kansas a ainter Richard Estes has a place ly man with a warm twinkle in his eyes that it is beautifully decorated, the house is more ontemporary c already secured in history accompanies his easy smile. He is not par- defined by its spatial elegance than by the books as the leading proponent ticularly forthcoming about his work. This objects within it. of painterly photorealism–one is not because he is shy or secretive–in fact, The ostensible subject of our conversa- useum of m of the last true “isms” in art and he’s quite open and direct about his content tion is his Maine paintings, even though Pa movement that changed the way we un- and techniques–but rather because, like so his artistic accomplishment was built on his derstand realism: While “realism” had been many accomplished painters, he relies more paintings of New York. So we begin there. gauged by accuracy and verisimilitude, its on his eye and his sensibilities than on ex- I ask Estes why his Paris Street Scene standard is now the photograph. -

Aurora Robson Responds to Idelle Weber's Photorealist Paintings with New Works in Exhibition That Features Both Artists' Ex

Aurora Robson Responds to Idelle Weber’s Photorealist Paintings with New Works In Exhibition that Features Both Artists’ Explorations of the Aesthetic and Material Qualities of Trash On View January 14 – February 20, 2021 Hollis Taggart is pleased to announce a two-person exhibition of work by Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson. Remnant Romance, Environmental Works: Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson will feature oil paintings and watercolors by Weber (1932-2020) alongside new multimedia sculptural work by Robson (b. 1972), who studied the late artist’s work while creating new pieces for the exhibition. Remnant Romance will create a dialogue between the artists, who, despite working in different media and being part of distinct generations, both draw inspiration from trash and seek to find beauty in the remnants of other peoples’ lives. Remnant Romance, Environmental Works: Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson will be on view at Hollis Taggart at 521 West 26th Street from January 14 through February 20, 2021. Idelle Weber is perhaps most well known for her contribution to Pop Art and her famous silhouette paintings, in which she depicted anonymous figures doing quotidian activities against nondescript backgrounds. In the late 1960s, continuing to find inspiration in the everyday but shifting in style to photorealism, Weber turned her attention to overlooked common daily sights in New York City such as fruit stands and street litter. The artist’s photorealist paintings were a continuation of the consumerism reflected in her Pop Art works, and were exhibited more widely. Over the past decade, however, Weber’s Pop Art has received more attention, largely due to curator Sid Sach’s inclusion of her silhouette paintings in his Beyond the Surface and Seductive Subversion exhibitions in 2010. -

Drugs, Microbes, and Antimicrobial Resistance Polyxeni Potter*

ABOUT THE COVER Drugs, Microbes, and Antimicrobial Resistance Polyxeni Potter* f America is to produce great painters,” wrote great American painter “IThomas Eakins (1844–1916), young artists should “remain in America to peer deeper into the heart of American life” (1). Eakins traveled abroad, where he became familiar with the work of 19th-century greats Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and Edgar Degas, but returned home to become a master of realism whose exactness and precision influenced many 20th-century American painters, one of them Richard Estes. Estes, a native of Kewanee, Illinois, grew up in Chicago and attended the city’s famed Art Institute. Upon graduation in 1956, he moved to New York to pursue a career in graphic design as freelance illustrator for magazines and advertising agencies. In the next 10 years, he crossed over to fine art and had his first exhibit around 1968 (2). An admirer of Eakins, Estes peered deeply into the American cityscape for a new style of art, true not only to his native culture but also to his times. This style evoked the traditions of trompe l’oeil (fooling the eye through photo- graphic illusion) and of 17th-century Dutch painting to create a contemporary version of reality (3). “When you look at a scene or an object you tend to scan it. Your eye travels around and over things. As your eye moves the vanishing point moves,” Estes said in an interview. “…to have one vanishing point or per- fect camera perspective is not realistic” (4). Drawing from his surroundings rather than the imagination, Estes used pho- tography to collect images or frozen moments of light on surfaces to comple- ment his own recollection of places and objects.