Petition of James Williams' Little River Regiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 ______January 2006

Vol. 3 No. 1.1 _____ ________________________________ _ __ January 2006 th Return to the Cow Pens! 225 Backyard Archaeology – ARCHH Up! The Archaeological Reconnaissance and Computerization of Hobkirk’s Hill (ARCHH) project has begun initial field operations on this built-over, urban battlefield in Camden, South Carolina. We are using the professional-amateur cooperative archaeology model, loosely based upon the successful BRAVO organization of New Jersey. We have identified an initial survey area and will only test properties within this initial survey area until we demonstrate artifact recoveries to any boundary. Metal detectorist director John Allison believes that this is at least two years' work. Since the battlefield is in well-landscaped yards and there are dozens of homeowners, we are only surveying areas with landowner permission and we will not be able to cover 100% of the land in the survey area. We have a neighborhood meeting planned to explain the archaeological survey project to the landowners. SCAR will provide project handouts and offer a walking battlefield tour for William T. Ranney’s masterpiece, painted in 1845, showing Hobkirk Hill neighbors and anyone else who wants to attend on the final cavalry hand-to-hand combat at Cowpens, hangs Sunday, January 29, 2006 at 3 pm. [Continued on p. 17.] in the South Carolina State House lobby. Most modern living historians believe that Ranney depicted the uniforms quite inaccurately. Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion cavalry is thought to have been clothed in green tunics and Lt. Col. William Washington’s cavalry in white. The story of Washington’s trumpeter or waiter [Ball, Collin, Collins] shooting a legionnaire just in time as Washington’s sword broke is also not well substantiated or that he was a black youth as depicted. -

Battle of the Shallow Ford

Bethabara Chapter of Winston-Salem North Carolina State Society Sons of the American Revolution The Bethabara Bugler Volume 1, Issue 22 November 1, 2020 Chartered 29 October 1994 Re-Organized 08 November 2014. The Bethabara Bugler is the Newsletter of the Bethabara Chapter of Winston-Salem. It is, under normal circumstances, published monthly (except during the months of June, July, and August when there will only be one summer edition). It will be distributed by email, usually at the first of the month. Articles, suggestions, and ideas are welcome – please send them to: Allen Mollere, 3721 Stancliff Road, Clemmons, NC 27012, or email: [email protected]. ----------------------------------------- Bethabara Chapter Meetings As you are aware, no Bethabara Chapter SAR on-site meetings have been held recently due to continuing concerns over the Corona virus. On September 10, 2020, the Bethabara Chapter did conduct a membership meeting via Zoom. ----------------------------------------- Page 1 of 19 Commemoration of Battle of the Shallow Ford Forty-seven individuals wearing protective masks due to the Covid-19 pandemic, braved the inclement weather on Saturday, October 10, 2020 to take part in a modified 240th Commemoration Ceremony of the Battle of the Shallow Ford at historic Huntsville UM Church. Hosted by the Winston-Salem Bethabara Chapter of the Sons of The American Revolution (SAR), attendees included visitors, Compatriots from the Alamance Battleground, Bethabara, Nathanael Greene, Catawba Valley, and Yadkin Valley SAR Chapters as well as Daughters of The American Revolution (DAR) attendees from the Battle of Shallow Ford, Jonathan Hunt, Leonard's Creek, Colonel Joseph Winston, and Old North State Chapters. -

Summary of Proposed National Register/Georgia Register Nomination

SUMMARY OF PROPOSED NATIONAL REGISTER/GEORGIA REGISTER NOMINATION 1. Name: Brier Creek Battlefield 2. Location: Approximately one mile south of Old River Road along Brannen Bridge Road, Sylvania vicinity, Screven County, Georgia 3a. Description: Brier Creek Battlefield is located largely within the state of Georgia’s Tuckahoe Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Screven County. The battlefield is delineated in the Georgia Archaeological Site Files as archaeological Site 9SN254. The National Register historic district boundary comprises 2,686 acres of this site: 2,521.3 acres are owned by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources as part of the Tuckahoe WMA, while 164.7 acres are privately owned by Warsaw Pines and Timberland LLC, in a silviculture area known locally as Chisolm Farm. These two tracts contain thirteen contributing resources and one noncontributing resource, all of which are archaeological sites, clustered in the western half of the district. The battlefield is located on a natural peninsula formed by the confluence of Brier Creek and the Savannah River. The topography is relatively low and flat, and vegetation consists of mature stands of planted loblolly pine trees actively managed for silviculture. Anhydric soils in the peninsula are surrounded by wet, swampy cypress forests which border Brier Creek and the Savannah River. A dirt road loops the peninsula, running southeast from Brannen Bridge Road. The property’s integrity of location and association are evidenced by historic documentation along with the recovery of military artifacts during archaeological studies, while the open pine forest, bordering cypress swamps, and the battlefield’s overall rural character effectively portray integrity of setting and feeling. -

The SAR Colorguardsman

The SAR Colorguardsman National Society, Sons of the American Revolution Vol. 5 No. 1 April 2016 Patriots Day Inside This Issue Commanders Message Reports from the Field - 11 Societies From the Vice-Commander Waxhaws and Machias Old Survivor of the Revolution Color Guard Commanders James Barham Jr Color Guard Events 2016 The SAR Colorguardsman Page 2 The purpose of this Commander’s Report Magazine is to o the National Color Guard members, my report for the half year starts provide in July 2015. My first act as Color Guard commander was at Point interesting TPleasant WVA. I had great time with the Color Guard from the near articles about the by states. My host for the 3 days was Steve Hart from WVA. Steve is from my Home town in Maryland. My second trip was to South Carolina to Kings Revolutionary War and Mountain. My host there was Mark Anthony we had members from North Car- information olina and South Carolina and from Georgia and Florida we had a great time at regarding the Kings Mountain. Went home for needed rest over 2000 miles on that trip. That activities of your chapter weekend was back in the car to VA and the Tomb of the Unknown. Went home to get with the MD Color Guard for a trip to Yorktown VA for Yorktown Day. and/or state color guards Went back home for events in MD for Nov. and Dec. Back to VA for the Battle of Great Bridge VA. In January I was back to SC for the Battle of Cowpens - again had a good time in SC. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

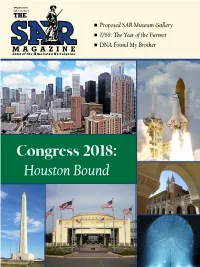

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights. -

Mcminn County Index of Pensioners

Revolutionary War Pensioners of McMinn County Index of Pensioners: Allen, Benjamin Evans, Samuel Lusk, Joseph Riggins, John Allgood, John Forester/Forister, Robert May, John Roberts, Edmund Barnett, William Hale, William May, William Russell, Moses Benson, Spencer Hambright, John McAllister, William Sampley/Sample Jesse Bigham, Andrew Hamilton, James McClung, John Schrimshear, John Billingsley, Walter Hampton, William McCormick, Joseph Smith, Henry Blair, Samuel Hankins, James McCormick, Robert Smithhart, Darby Bradley, William Helton, Peter McMahan, Robert Snow, Ebenezer Brown, Benjamin Hughes, John McNabb, David Stanfield, James Broyles, Daniel Hyden, William McPherson, Barton Steed, Thomas Carruth, John Isom, Elijah Murphy, Edward Thompson, Thomas Carter, Charles, Sr. Johnston, Thomas Norman, William Walling (Walden), John Cochran, Barnabas Kelly, William Norris, John Ware, Rowland/Roland Coffey, Eli Kincanon, George Peters, William Weir, David Crye, William Lane, Isaac Price, Reese Witt, Burgess Cunningham, James Larrimore, Hugh Queener, John Witt, Earis (Eris, Aires,Ares) Curtis, John Lesley, Thomas Rector, Maximillian Young, Samuel Dodd, William Liner, Christopher Reid, David Douglas, Robert Longley, William Benjamin Allen Pension Application of Benjamin Allen R106 Transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris State of Tennessee } SS McMinn County } On this 2 day of Dec’m. 1844 personally appeared in open nd Court before the worshipful County Court Mr Benjamin Allen a resident in the County and State aforesaid aged Eighty one years -

An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America

Painted by Captn. W McKenzie BATTLE OF CULLODEN. An Historical Account OF THE Settlements of Scotch Highlanders IN America Prior to the Peace of 1783 TOGETHER WITH NOTICES OF Highland Regiments AND Biographical Sketches BY J.P. Maclean, Ph.D. Life Member Gaelic Society of Glasgow, and Clan MacLean Association of Glasgow; Corresponding Member Davenport Academy of Sciences, and Western Reserve Historical Society; Author of History of Clan MacLean, Antiquity of Man, The Mound Builders, Mastodon, Mammoth and Man, Norse Discovery of America, Fingal's Cave, Introduction Study St. John's Gospel, Jewish Nature Worship, etc. ILLUSTRATED. THE HELMAN-TAYLOR COMPANY, Cleveland. JOHN MACKaY, Glasgow. 1900. Highland Arms. To Colonel Sir Fitzroy Donald MacLean, Bart., C.B., President of The Highland Society of London, An hereditary Chief, honored by his Clansmen at home and abroad, on account of the kindly interest he takes in their welfare, as well as everything that relates to the Highlands, and though deprived of an ancient patrimony, his virtues and patriotism have done honor to the Gael, this Volume is Respectfully dedicated by the Author. "There's sighing and sobbing in yon Highland forest; There's weeping and wailing in yon Highland vale, And fitfully flashes a gleam from the ashes Of the tenantless hearth in the home of the Gael. There's a ship on the sea, and her white sails she's spreadin', A' ready to speed to a far distant shore; She may come hame again wi' the yellow gowd laden, But the sons of Glendarra shall come back no more. The gowan may spring by the clear-rinnin' burnie, The cushat may coo in the green woods again. -

William Thompson S30731

Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension application of William Thompson S30731 f29NC Transcribed by Will Graves rev'd 7/20/17 & 9/5/21 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading and to facilitate searches of the database. Where the meaning is not compromised by adhering to the spelling, punctuation or grammar, no change has been made. Corrections or additional notes have been inserted within brackets or footnotes. Blanks appearing in the transcripts reflect blanks in the original. A bracketed question mark indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. The word 'illegible' or 'indecipherable' or ‘undeciphered’ appearing in brackets indicates that at the time I made the transcription, I was unable to decipher the word or phrase in question. Only materials pertinent to the military service of the veteran and to contemporary events have been transcribed. Affidavits that provide additional information on these events are included and genealogical information is abstracted, while standard, 'boilerplate' affidavits and attestations related solely to the application, and later nineteenth and twentieth century research requests for information have been omitted. I use speech recognition software to make all my transcriptions. Such software misinterprets my southern accent with unfortunate regularity and my poor proofreading skills fail to catch all misinterpretations. Also, dates or numbers which the software treats as numerals rather than words are not corrected: for example, the software transcribes "the eighth of June one thousand eighty six" as "the 8th of June 1786." Please call material errors or omissions to my attention. -

Backcountry Warrior: Brig. Gen. Andrew Williamson the “Benedict Arnold of South Carolina” and America's First Major Double

Backcountry Warrior: Brig. Gen. Andrew Williamson The “Benedict Arnold of South Carolina” and America’s First Major Double Agent -- Part I BY LLEWELLYN M. TOULMIN, PH. D., F.R.G.S. This two-part series contains the following sections: Introduction Acknowledgements Biography of Brigadier General Andrew Williamson White Hall Possible Link to Liberia Archaeological Reconnaissance of 1978 Archaeological Survey of March 2011 Archaeological Expedition of 2011-12 Conclusions Biographical Note. Introduction Andrew Williamson was a fascinating and very controversial character in South Carolina Revolutionary history. He was loved by his many supporters and reviled by his many enemies. He was called the “Benedict Arnold of South Carolina” for laying down his arms in June 1780 and taking British protection. He surprised his critics, however, by revealing after the war that for a crucial period while living in besieged Charleston he had spied against the British, and had passed vital intelligence to the Americans. Because of his high rank and important information passed on for almost a year, he can fairly be described as “America’s first major double agent.” Despite his fame and notoriety, and historical importance, no biography of Williamson longer than a page or two has ever been published. Furthermore, no book on spy-craft in the Revolution has focused on Williamson or apparently even mentioned him and his spying efforts.1 1 Some of the relevant books that do not mention Williamson’s spying activities include: Harry and Marjorie Mahoney, -

Vol. 3 No. 12.3______December 2006

Vol. 3 No. 12.3______________________________________________________ __December 2006 Christmas Greetings from SCAR Camp Blessings to All this New Year “Brothers in Arms” painting by Darby Erd showing five actual members of the South Carolina 3d Regiment of the Continental Line at the Purrysburg redoubt on the Savannah River. Biographies of those men pictured above: Catawba Indian Peter Harris, p. 32; Robert Gaston, p. 33; “free Negro” Drury Harris, p. 33; “Negro Adam”, p. 34; David Hopkins, p. 34. See related unit history on page 28. Painting © 2005, 2006 Cultural & Heritage Museums. In This Edition: Battle of Burke County Jail…..…….……………...……15 Editor / Publisher’s Notes……………………..……….…2 Patriot Gen. John Twiggs……………………….…….…16 Upcoming SCAR events…………………..….…….3 and 6 Patriot Lt. Col. James McCall………………….……….19 Southern Revolutionary War Institute………..…………5 1779 Journal of British Major Francis Skelley…….…..24 Digging for Information: Archaeology...…….…...…...…7 History of the Third SC Continental Regiment…….….28 Letters to the Editor……………………………………..10 Biographies of SCIII soldiers in painting……………....32 Calendar of Upcoming Events……………………..……13 Pension Statement - Patriot Marshall Franks…..….….36 1 Editor / Publisher’s Notes Southern Campaigns Roundtable Meeting Great things have been affected by a few men well Southern Campaigns Roundtable will meet on December 9, 2006 conducted. George Rogers Clark to Patrick Henry, in Pendleton, SC at the historic Farmers Hall (upstairs) on the old Governor of Virginia, February 3, 1779. town square